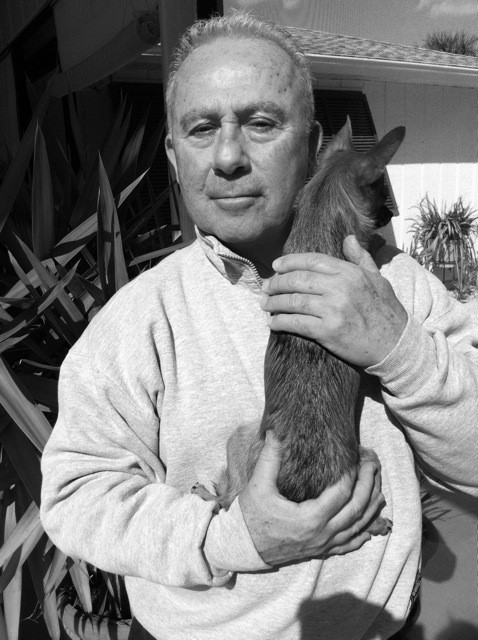

Henry Wessel

American

1942, Teaneck, New Jersey

2018, Point Richmond, Richmond

Image: © Calvert Barron

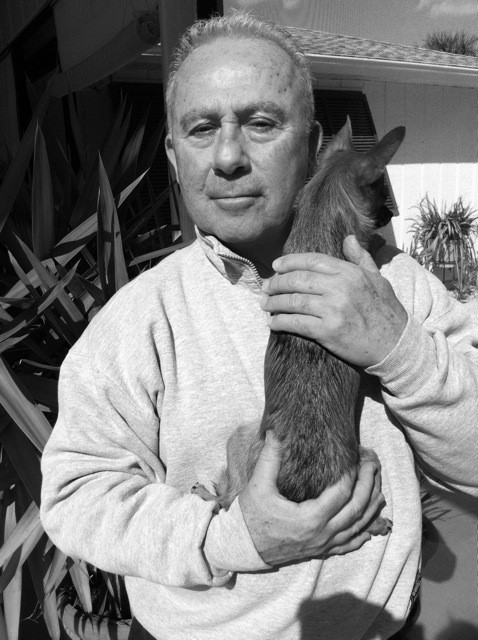

American

1942, Teaneck, New Jersey

2018, Point Richmond, Richmond

Image: © Calvert Barron

For four decades, Bay Area photographer Henry Wessel has observed and documented the brilliant light, vernacular architecture, and social landscape of Northern and Southern California.

Wessel came to photography almost accidentally during his years at Pennsylvania State University, but he was immediately hooked after first discovering (with a borrowed Leica) how the world looked through the camera's lens. He began to photograph seriously in 1967, inspired by the work of Wright Morris, Robert Frank, and Garry Winogrand, and in 1971 he was awarded a Guggenheim grant to document the landscape that flanks the American highway system, a once-natural terrain profoundly transformed by human presence. In the 1970s, Wessel became part of a generation of artists who challenged and expanded the categories of landscape and documentary photography, foregoing traditional views of pristine nature in favor of straightforward and personal depictions of the built environment.

Exploring the territory where nature and culture meet, Wessel's deadpan pictures share the spontaneity and authenticity of snapshots, combining disarming frankness with irreverent humor. His low-key style matches the modest nature of his subject matter: he has found an inexhaustible richness in the aesthetics of the everyday, turning the least monumental of subjects into a kind of personal poetry.

The artist on photographing on the road

Please note that artwork locations are subject to change, and not all works are on view at all times. If you are planning a visit to SFMOMA to see a specific work of art, we suggest you contact us at collections@sfmoma.org to confirm it will be on view.

Only a portion of SFMOMA's collection is currently online, and the information presented here is subject to revision. Please contact us at collections@sfmoma.org to verify collection holdings and artwork information. If you are interested in receiving a high resolution image of an artwork for educational, scholarly, or publication purposes, please contact us at copyright@sfmoma.org.

This resource is for educational use and its contents may not be reproduced without permission. Please review our Terms of Use for more information.