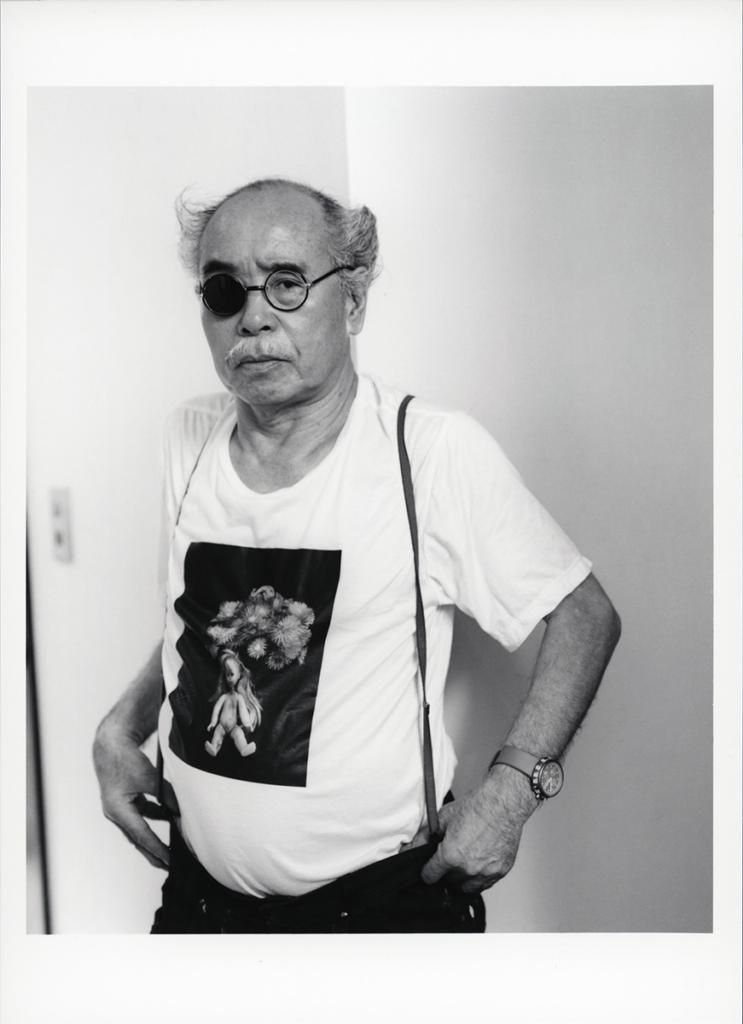

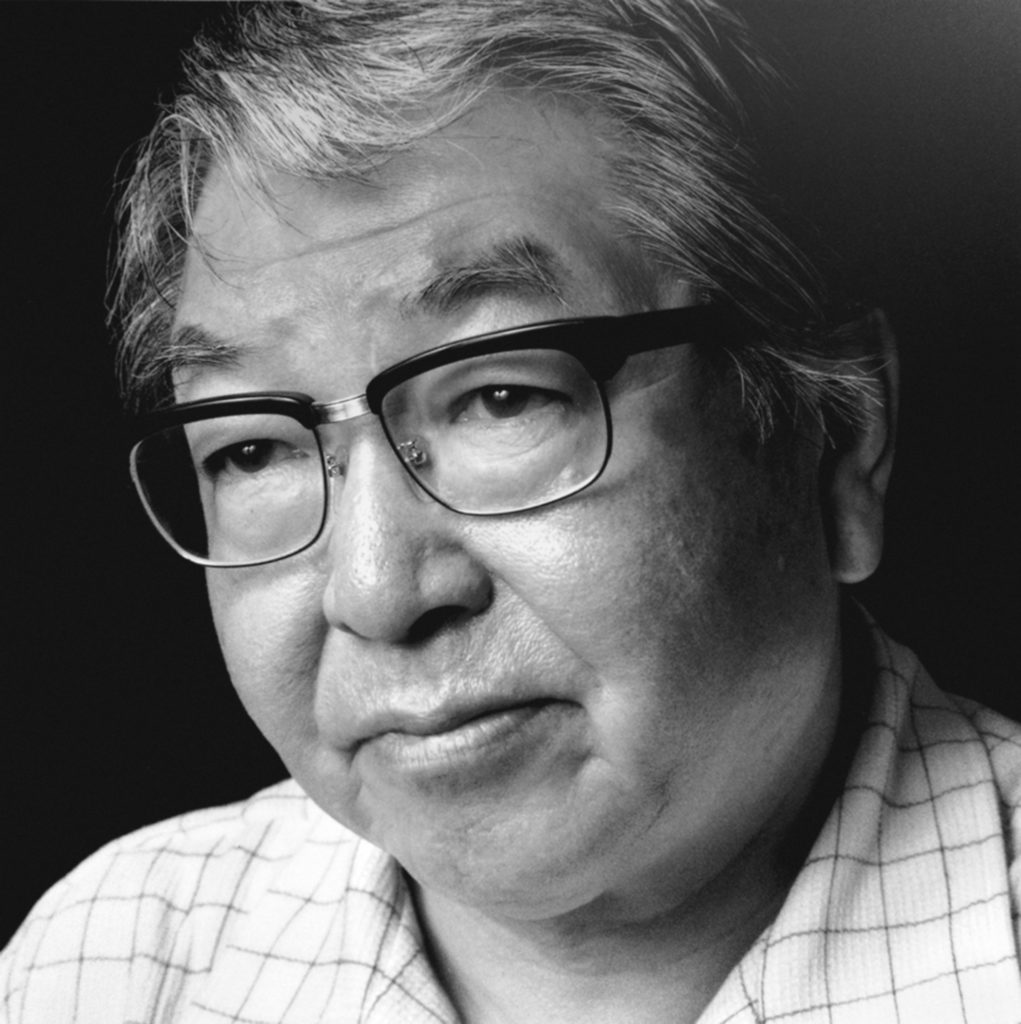

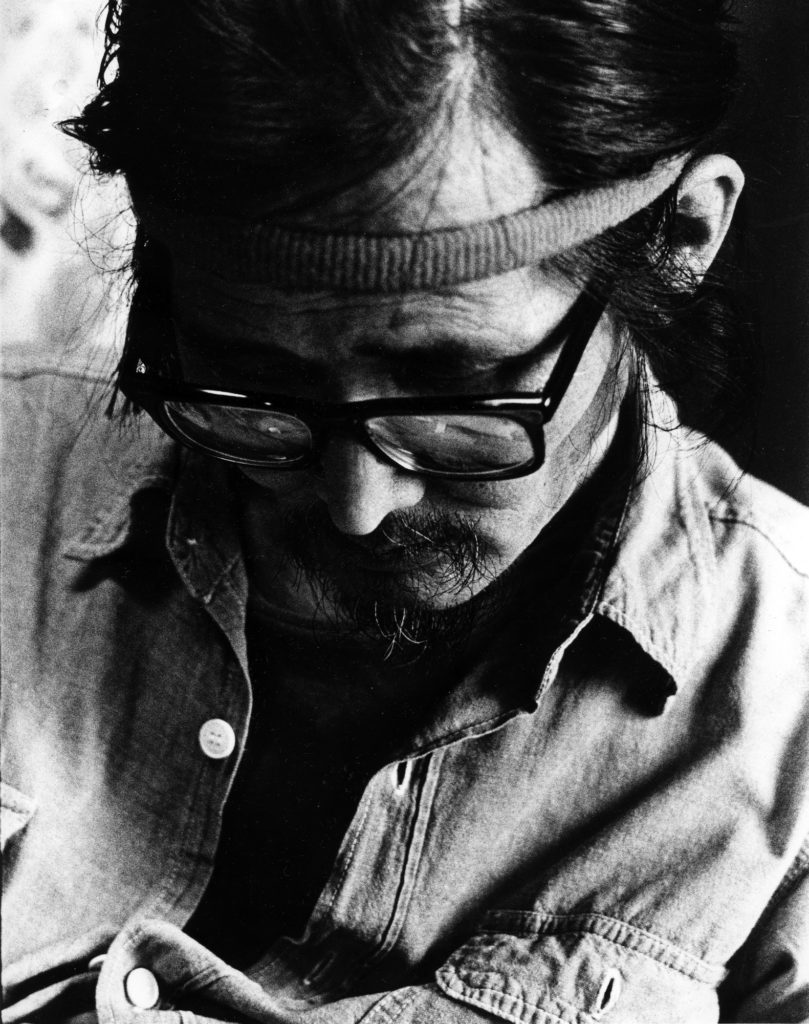

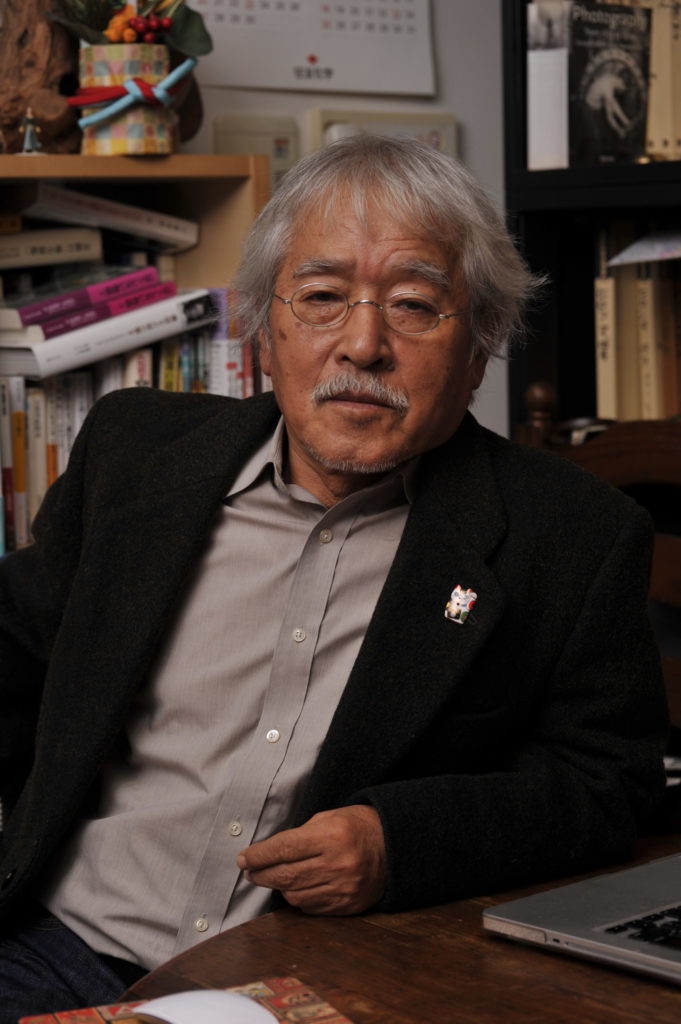

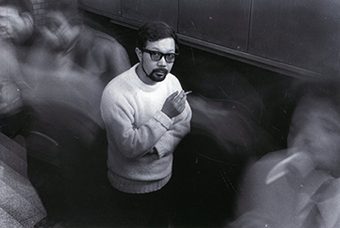

Artist

Shomei Tomatsu

Japanese

1930, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture

2012, Naha, Okinawa Prefecture

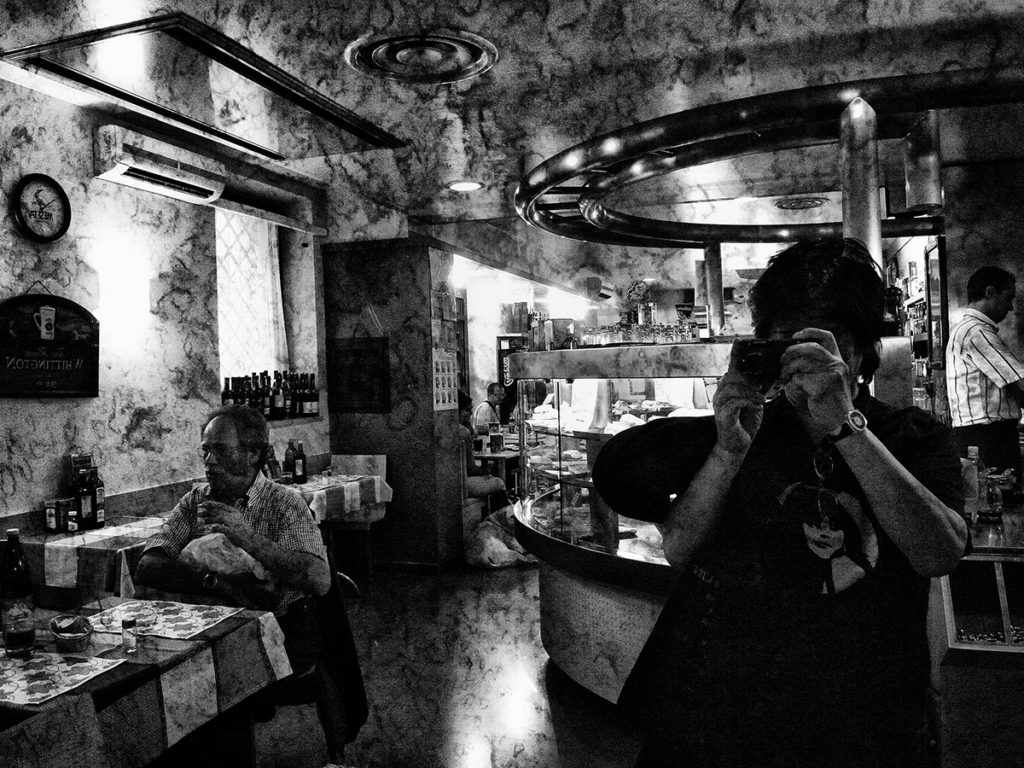

Shomei Tomatsu (1930–2012) created pictures that balance perilously between despair and admiration, anger and delight, articulating the essential conflicts he found in his country after World War II. Sharp and elegant, they are not so much descriptions as they are records of fleeting, unremarkable moments. The first photographer to explore the experience of postwar Japan and its ambiguous relationship to the United States, Tomatsu would portray this subject more thoroughly and intensely than any other photographer. Only toward the end of his life was the issue of the Americanization of his country somewhat lessened in his work.

Born in Nagoya, Tomatsu was fifteen years old when the war ended. “To have experienced only suffering, that is the characteristic of the children who knew the war,” he said.[1] He found his way to photography with the help of a sympathetic teacher and the modestly scaled, beautifully printed photography books for the general reader produced by the publisher Iwanami Shoten, for whom he would work briefly, from 1954 to 1956. Photography suited Tomatsu because he could work on his own, and most of his projects were self-assigned. His earliest subjects constituted an inquiry into the way his country was changing in the postwar years. He later recalled: “After the defeat, darkness and light became clearly visible and values shifted 180 degrees. . . . My most impressionable years were spent during those times, and that intense experience became a filter through which I’ve seen things ever since.”[2] Tomatsu’s first series, Disabled Veterans, Nagoya (1952) and Pottery Town, Seto, Aichi (1954), record poverty after the war and the persistence of a prewar artisan culture. Later, in Home, Amakusa, Kumamoto (1959), he acknowledged the beauty and richness of traditional Japan but also the unsustainability of the kind of life led in rural communities.

Quite early in his career Tomatsu discovered that his work, while depicting specific subjects, could resonate metaphorically as well. Defending his work against the criticism that he made a “photography of impressions” rather than truthful reports, he stated that he “did not remember ever discarding factual fidelity” but that “to avoid the sclerosis of photography, it was important to cast out the evil spirit of ‘reportage.’”[3] Thus a picture of the mud-spattered legs of a worker seen from behind, shovel in hand, shows an honest understanding of the conditions facing the country, especially for its rural inhabitants in the 1950s and 1960s, but Tomatsu's photographs also speak to Japan’s renewal, its essential fecundity. In making pictures that were engaged in his country’s issues without being journalistic, Tomatsu was fortunate to have support from magazines directed at amateurs, including Camera Mainichi, the principal publisher of important new photography in Japan, under the direction of editor Shoji Yamagishi.

By 1959 Tomatsu had established a pattern of finding subjects and returning to them later, or finding subjects in the present that were about the past. Chief among them was the condition of postwar Japan and the persistence of its past in the modern state, as in the Memory of War, Toyokawa, Aichi series (1959). “It was from the ruins of war that Japan was reborn, Phoenix-like,” he stated. “It was only from here that it could make a fresh start.”[4] His series Floods and the Japanese (1959), prompted by the destruction of his childhood home, represents both the devastation and the regenerative potential of flooding. Also in 1959, he began to document American military bases around Tokyo in the series Chewing Gum and Chocolate. This subject was especially resonant at that time, when the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty was being renegotiated amid intense domestic opposition.[5] Of all his subjects, it would be the one he persisted in most forcefully and inventively. The country’s active growth during this period is equally important to understanding the arc of Tomatsu’s career. As acknowledgment of this resurgence, Japan hosted the Olympic Games in 1964 and 1972 and the World Exposition in 1970, events that Tomatsu referenced in his work.

In addition to his own practice as a photographer, Tomatsu actively promoted photography in Japan. In 1959 he joined Ikko Narahara, Kikuji Kawada, Eikoh Hosoe, Akira Sato, and Akira Tanno to form the influential agency VIVO, modeled generally on the photographers’ cooperative Magnum, established twelve years earlier in Paris. Although VIVO disbanded after two years, it embodied the creative energy of the best postwar photography. In 1968, assisted by Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki (who would later found the journal Provoke), Tomatsu organized the groundbreaking exhibition A Century of Photography: A Historical Exhibition of Photographic Expression by the Japanese (also known as A Century of Japanese Photography). The first historical presentation of photography in Japan, surveying the period 1840 to 1945, it was shown through the Japan Photographers’ Association at the Seibu department store in northern Tokyo, for many years an important venue for contemporary art. Tomatsu was the central figure in New Japanese Photography, organized by John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi for the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1974; the exhibition traveled to SFMOMA the following year. This was the first recognition by an important museum outside Japan that significant work was being created by Japanese photographers.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s Tomatsu bore witness to the vibrant youth culture of Tokyo, mainly in evidence in Shinjuku, as well as the student protests there, seen especially in the Protest, Tokyo series (1969). Tomatsu traveled to Nagasaki for the first time in 1960 to photograph the victims of the 1945 atomic bombing. These pictures would be published, along with Ken Domon’s photographs of the hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bombings) in Hiroshima, the following year as Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document 1961, issued only in Russian and English. Tomatsu also photographed objects that showed the effects of the nuclear bombing: a stopped wristwatch, a commonplace bottle distorted by the intense heat, and details from the city’s cracked and ruined ancient Catholic cathedral. He would return to Nagasaki periodically over the years and later lived there. In 1969, at the height of the Vietnam War, he began to examine the special history of Okinawa, still heavily occupied by American forces as the principal military staging site in Japan for the conflict in Vietnam. His first trip there took place under the auspices of Asahi Camera, which published the resulting series; his book Okinawa, Okinawa, Okinawa was published by Shaken later that year. The renewal of the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty in 1970 focused Tomatsu’s attention, and that of many younger Japanese people, on the danger posed to the country by U.S. nuclear weaponry, even as social liberalization and exuberant economic resurgence were partly attributable to the American postwar presence. He returned to Okinawa twice in 1971, and again in 1972 to witness the return of the islands to Japanese control.

With the publication of The Pencil of the Sun in 1975, Tomatsu turned his attention from the American forces in Okinawa to the island’s ancient culture, finding a pre-Japanese culture still very much in evidence there. In his later work the American presence gradually became less of a focus. In the series Plastics (1988–89), he documented debris he found cast up on the shores of Chiba, where he then lived. After moving to Nagasaki in 1999, he photographed schoolchildren on the city’s streets and the aging hibakusha Senji Yamaguchi, whom he had photographed previously, in 1962—now no longer a victim but, seen from behind, an older man enjoying a boat ride. Tomatsu spent the last two years of his life in Okinawa.

— Sandra S. Phillips

Notes

- Shomei Tomatsu, “The Original Scene,” in Traces: Fifty Years of Tomatsu’s Works (Tokyo: Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 1999), 183. In Japan his generation was called the “Heretical Generation,” he writes: “It was a label that was affixed to the children who had experienced the war on both sides, regardless of whether they were on the winning or losing side.” As such, the term was used to refer to the American Beat generation and the French New Wave as well. Ibid., 183.

- Shomei Tomatsu, Chewing Gum and Chocolate: Shomei Tomatsu, ed. Leo Rubinfien and John Junkerman (New York: Aperture, 2014), 19.

- Shomei Tomatsu quoted in Nakahara Atsuyuki, “Tomatsu Shomei—Fifty Years of Innovation,” in Traces, 191.

- Shomei Tomatsu quoted in Traces, 184.

- Its passage was forced through in 1960, to the dismay of much of the population.