Two large figures dominate Sigmar Polke’s striking 2003 painting Untitled (fig. 1). A man wearing the heavy robes and long beard of a magician or sorcerer appears to be conjuring a spirit, rendered in ghostly lavender paint. Both figures stand within a circle on the floor, along with several objects that likewise suggest magical ritual—a skull, a book, two candles, and a jug. The depiction is at once recognizable and peculiar, the latter effect due in part to the work’s commanding, monumental scale and heightened by the prominent white stage curtain pulled back on the left, which frames the event as a performance and the viewer as an audience member.

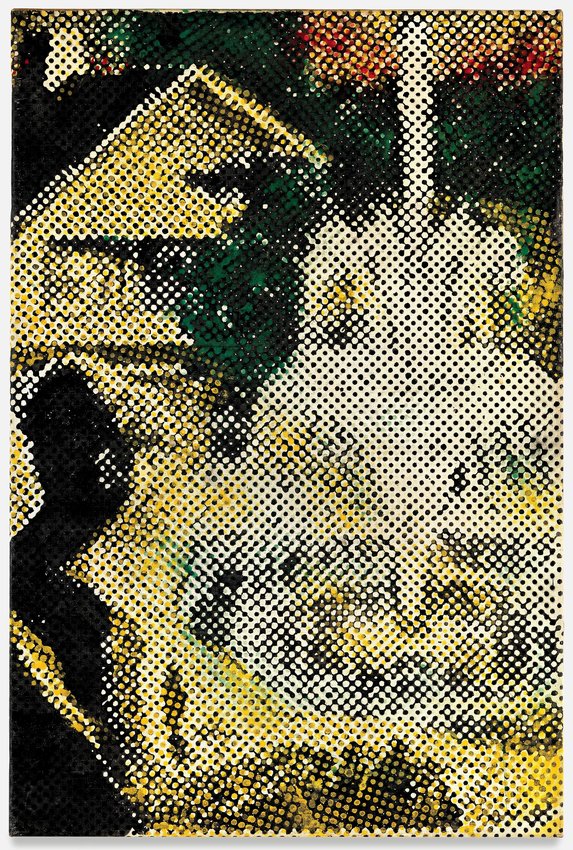

2. Sigmar Polke, Springbrunnen (Fountain), 1966; paint on linen, 41 x 27 1/2 in. (101.14 x 69.85 cm); The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; © Estate of Sigmar Polke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

One of the most significant German artists of the postwar period, Polke created a body of work that defies simplistic definitions or categorizations. Over the course of his decades-long career, he experimented with a wide range of subject matter and an array of mediums, from photography and film to painting and drawing. Polke came of age as an artist in West Germany in the years following World War II, when technological innovations in the mass media, commercial production, and space travel conveyed a sense of progress that was countered by the intense anxiety of global annihilation bred by the Cold War. In the early 1960s he began to depict everyday subject matter and mass-media images in his paintings and drawings. To create the series of works known as the Rasterbilder, he magnified found images that had been printed using the dot-screen process typical of mass reproduction; he then hand painted the enlarged patterns of raster or benday dots from which the images were composed onto his canvases. Springbrunnen (Fountain, 1966, fig. 2) depicts a garden fountain in front of a nondescript modern house of the type commonly seen in 1950s West Germany. The result is not simply a banal image of a suburban home, however: Polke rearranged the raster dots to make a complicated, distorted pattern, highlighting the photomechanical printing process.

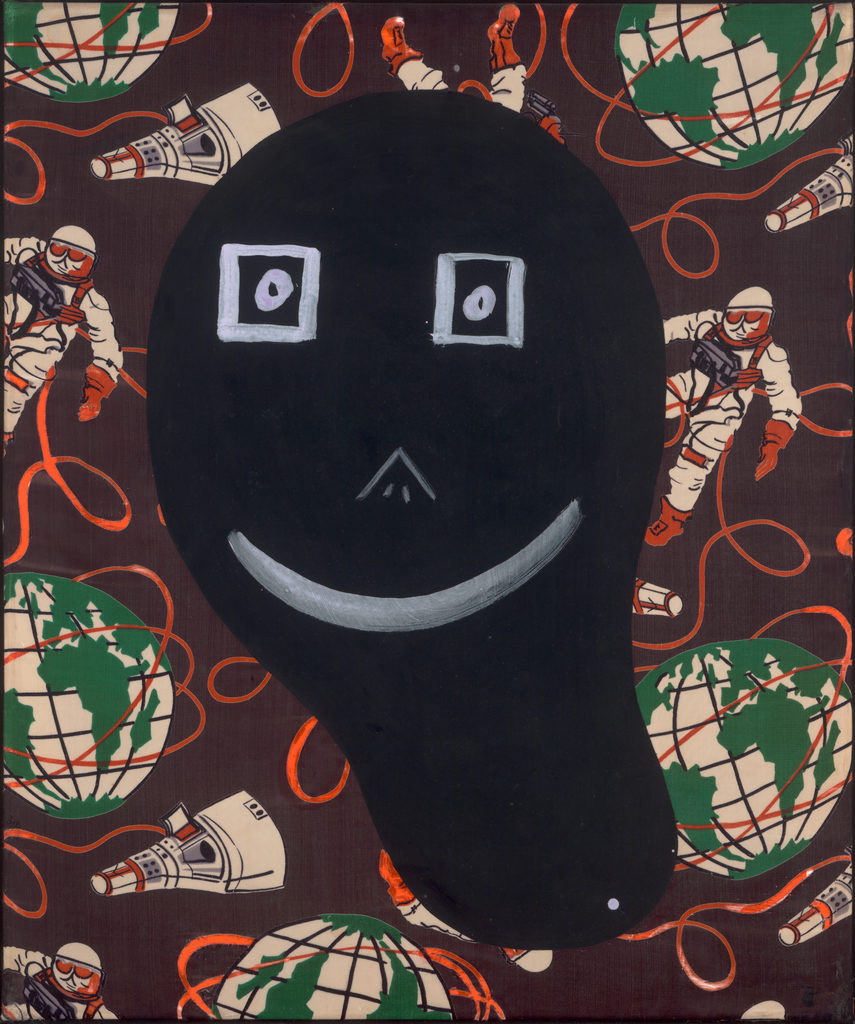

3. Sigmar Polke, Polke als Astronaut (Polke as Astronaut), 1968; dispersion paint on fabric, 35 1/2 x 29 1/2 in. (90.2 x 74.9 cm); promised gift of a private collection to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; © Estate of Sigmar Polke / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

In the late 1960s and early 1970s Polke also began using commercially produced patterned fabrics in his paintings, typically inexpensive textiles associated with the domestic sphere.1 Employed in lieu of canvas, the cloth provided a support as well as a design element. In Polke als Astronaut (Polke as Astronaut, 1968, fig. 3), for example, he selected a fabric that might be at home in a child’s bedroom, printed with pictures of astronauts floating in space. Over this he painted a balloon with a smiling face. The fabric carries a particular historical nuance, calling to mind the Cold War space race. In addition, by replacing the iconic blank canvas with a recognizable mass-produced pattern and combining the images printed on the fabric with those he painted himself, Polke playfully examined a fundamental element of painting and provoked the viewer to question the relationship between commercial and fine art production.

Like the Rasterbilder, Polke’s cloth pictures allude to the rapid influx of consumer goods and the rise of consumer culture that were central to West German reconstruction after the war. They speak too to the palpable atmosphere of a divided Germany, where consumerism was ideologically welded to the concepts of freedom and democracy in the West.2 While shifting notions of consumption and media are deeply embedded in Polke’s work, he was also investigating the history of art, using depictions of everyday objects, common materials, and banal source images to examine the nature of painting, in particular its materiality.

In Untitled, as in the cloth paintings, Polke once again highlighted the support of the painting. Here he rendered the image not on a patterned cloth, but on a transparent surface that allows the viewer to see through to the work’s structural bones. The exposed stretcher bars bisect the two figures both horizontally and vertically. Those running through the spirit or ghost are completely visible, playing an optical trick: the image appears to be both in front of and behind the support simultaneously. The image of the magician is more opaque, and the bars are clearly situated behind the painted figure; the opacity also gives the figure more prominence within the composition. On the left, the horizontal bar that crosses the center of the work disappears behind the curtain. In order to create this play with transparency, Polke painted the sorcerer and the stage curtain on the back as well as the front of the fabric. Perhaps recalling his own training as a glass painter, the process is reminiscent of a traditional Bavarian technique called hinterglasmalerei, or reverse-glass painting, which involves applying the medium to the back of the glass so that the finished painting is viewed through rather than on it.3 In Untitled, the transparent fabric and the various levels of opacity in the image create confusion between foreground and background, and between the front and back of the painting.

Just as Polke foregrounded the structure of mechanically reproduced imagery in his Rasterbilder, in Untitled he mimics the woodblock print, another commercial reproduction technique, as seen in the stark lines and absence of chiaroscuro shading in the figures and the curtain. Used to illustrate books following the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century, woodcut printing is a far older technique than the dot-screen printing of twentieth-century newspapers and magazines. Yet it similarly relates to the world of popular entertainment, advertising, and decoration, as it was long a common medium for printing playing cards, game boards, and posters.4

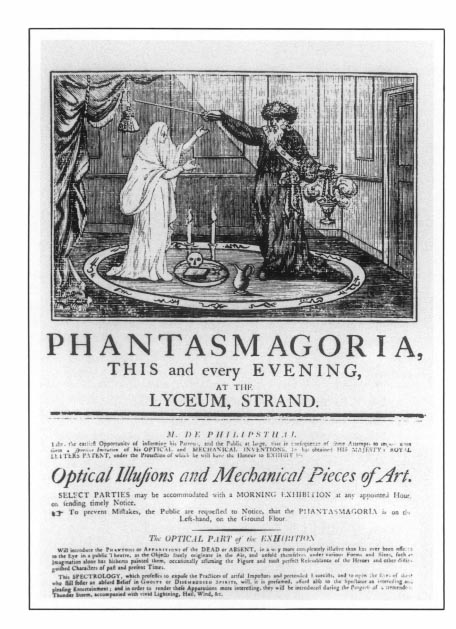

4. Show bill for a phantasmagoria performance by Paul de Philipsthal, London, 1802

Polke frequently incorporated imagery from woodcut prints, etchings, and photographs in his work. Examining these sources reveals his dense layering of meaning through historical reference as well as through materials and processes. The scene depicted in Untitled can be traced to a show bill for an October 1802 phantasmagoria act in London (fig. 4). Popular in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Europe, and later in the United States, phantasmagoria productions used a modified magic lantern to project frightening images such as spirits, ghosts, and demons onto transparent glass, which made them appear as if they were floating in space. Multiple projectors created the illusion that the images were moving and changing shape.5

The rise in popularity of phantasmagoria acts can be attributed, in part, to a shift in post-Enlightenment society away from long-held beliefs in the mystical and alchemical and toward a popular interest in technology, science, and rationality.6

Art historian Jonathan Crary notes that naturally occurring optical illusions such as afterimages had been understood since antiquity as instances of magic and sorcery, but that this changed as technological and scientific advances fostered an understanding of how illusions are constructed and the effect of environmental conditions on phenomenological and corporeal experience.7

The phantasmagoria show mediated between these two poles, as viewers were subjected to darkness, disorienting sounds, and eerie, mysterious floating images, all re-creating the emotional aura of a supernatural encounter, while the spectacle was coded as entertainment.

Likely selected by Polke for its intriguing relationship to the history of illusionism as a mode of performance, the show bill advertises a production by Paul de Philipsthal, a pioneer in phantasmagoria who was invested in staging such experiences as artful, well-crafted illusions. Historian Terry Castle notes that the early magic-lantern shows developed as a mock scientific exercise in the demystification of illusions and the ancient belief in the supernatural,8

as the text on de Philipsthal’s show bill suggests: “This SPECTROLOGY . . . professes to expose the Practices of artful Impostors and pretended Exorcists, and to open the Eyes of those who still foster an absurd Belief in Ghosts or Disembodied Spirits.”9

Like Polke’s painting, the source image alludes to the history of illusionism, particularly the use of technology to shape visual experience. Presumably chosen by de Philipsthal due to his interest in discrediting illusionists as “Impostors,” the image is thought to depict an eighteenth-century German “wizard” from Leipzig named Johann Georg Schröpfer, who was famous for staging bogus séances.10

Schröpfer sold himself as the real thing despite his use of a magic lantern to create his illusions.11

There is a constant push and pull between “high” and “low” art in Untitled, evident in its use of a source image from the world of entertainment, but also in Polke’s painting method. Polke turned his source images or reproductions into new originals by painting his works by hand. To create the scene in Untitled, he projected a transparency of the found image onto fabric treated with resin. The skewed perspective of the painted scene suggests that he placed the projector at an angle to the canvas. The frame of the original image appears at the top and bottom of the canvas, with space above and below, clearly indicating—like the visible stretcher bars—that this is a painted, constructed picture rather than a “window” onto the scene. Polke also painted each of the rectangular panels on the wall behind the two figures in a different color. These panels take on a new meaning with this gesture: they are no longer architectural elements, as in the original image, but now appear to be monochrome paintings lining the wall. In the twentieth century, with the rise of modernism, the purely abstract monochrome canvas represented the total reduction of painting to its simplest, most elemental form and was associated by some with spiritual purity. Here these anti-illusionist panels are juxtaposed with a multifaceted source image advertising a fantastical, magical performance.

Polke often aimed to underscore connections among magic, deception, history, and technology in his work. Intrigued by the notion of perception and vision being in constant flux, he examined not only how vision shifts in time and in space but also how it blends with memory. In Untitled, vision in myriad forms takes center stage, from the history of technological interventions such as the magic lantern, to the act of viewing an object like a painting or a poster. Juxtaposing mass-produced printed matter with the tradition of large-scale painting, both nineteenth-century history painting and twentieth-century modernist abstraction, Polke’s work exposes the artifice and illusionism of art itself, in particular that of the preeminent high art form, painting. Untitled presents painting as an object, one grounded in reality but shrouded with mystical illusions and fantasies of what lies beyond the physical realm.

Notes

- See Christine Mehring, “Polke’s Patterns,” in Kathy Halbreich, ed., Alibis: Sigmar Polke, 1963–2010 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2014), 234–41.

- See Mark Godfrey, “From Moderne Kunst to Entartete Kunst: Polke and Abstraction,” in Halbreich, Alibis, 121.

- Hinterglasmalerei has a long history in the visual arts and was most famously championed in the early twentieth century by the expressionist painters Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter. See Mildred Lee Ward, Reverse Painting on Glass (Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, 1978).

- Richard S. Field, Fifteenth-Century Woodcuts and Metalcuts from the Collection of the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1965).

- Invented in the seventeenth century, the magic lantern was originally employed for religious instruction, before being adopted for entertainment. The magic lantern is thus a direct ancestor of the motion picture projector, in a lineage of technological progress from the inception of Renaissance perspective to the modern mass media. See Martin Hentschel, “In the Universe of Transparency: Sigmar Polke’s Laterna Magica,” in Sigmar Polke: Laterna Magica, ed. Brigitte Kölle (Frankfurt: Portikus, 1995), 9–11.

- For more on the history of the phantasmagoria, see Terry Castle, “Phantasmagoria: Spectral Technology and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie,” Critical Inquiry 15, no. 1 (Autumn 1988): 26–61.

- People claiming to be sorcerers had often used technology or intervention to mimic optical phenomena such as afterimages, but, Crary writes, “with Goethe and the physiologists who followed him, there was no such thing as an optical illusion: whatever the healthy corporal eye experienced was in fact optical truth.” Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 97–98.

- Terry Castle, “Phantasmagoria: Spectral Technology and the Metaphorics of Modern Reverie,” 30.

- This transcription is found in the dossier “Magic Lantern,” in the Dead Media Archive, published by New York University’s Department of Media, Culture, and Communication, https://cultureandcommunication.org/deadmedia/index.php/Magic_Lantern.

- Mervyn Heard, who has published extensively on the history of the magic lantern, believes that de Philipsthal used a preexisting woodcut for his show bill; the original source image is currently unknown. Mervyn Heard, email to the author, November 21, 2015.

- According to Heard, de Philipsthal’s early performances, in Vienna, were titled Schröpferesque Geister Erscheinungen, or “Schröpfer-esque spirit sightings,” poking fun at the German wizard for proclaiming his genuine ability to raise spirits from the dead. See Mervyn Heard, Phantasmagoria: The Secret Life of the Magic Lantern (London: The Projection Box, 2006), 204.