-

Summary

-

Introduction

-

Murals

-

Biographies

-

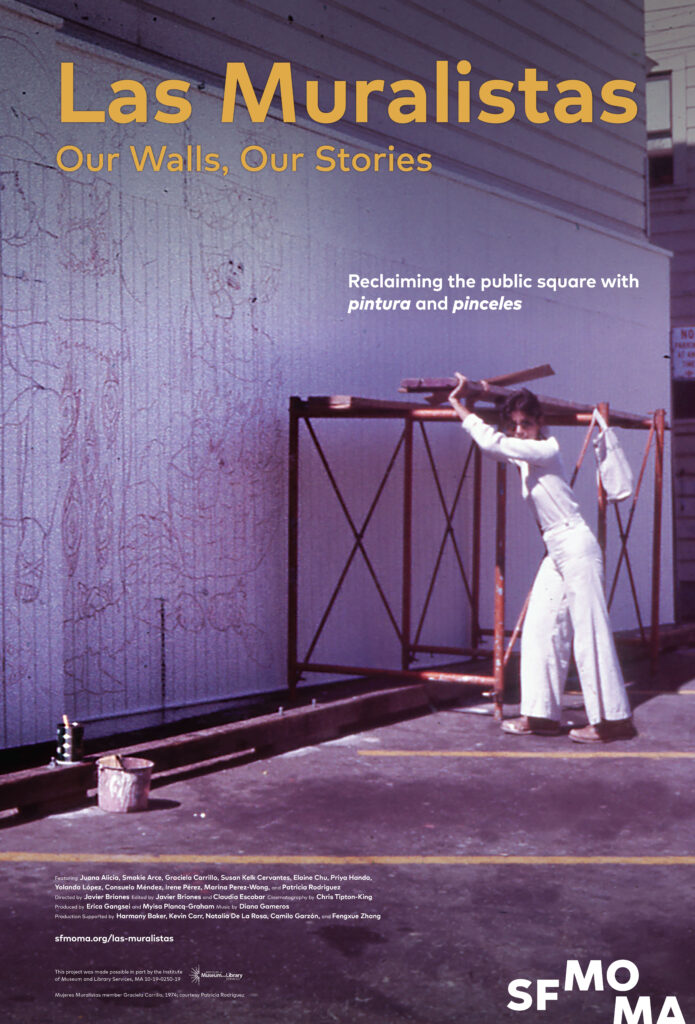

Documentary

-

Audio Zine

-

Oral Histories

-

Essays

-

Primary Sources

-

Contributors

-

Community Advisory Committee

-

Project Team

Summary

Proyecto Mission Murals examines the origins of the community mural movement in San Francisco’s Mission District over close to two decades, from 1972 to 1988. Created in collaboration with community partners, the project includes documentation of murals created in the Mission District between 1972 and 1988, accompanied by reference images. It also features materials generously provided by the muralists themselves, the Mission community members and organizations that have supported their work, and scholars and journalists who have chronicled their activity, including interviews, essays, a documentary film, an audio zine, primary sources, and new artist biographies.

The interdisciplinary nature of Proyecto Mission Murals reflects the complexities and richness of the community mural movement. Rather than a cohesive or seamless narrative, this project conveys its wide-ranging aesthetics, the diversity of its participants, its changing nature, and the perpetual challenges faced by its artists.

Introduction

By Cary Cordova

As an artform, murals have a long history, but their rapid and expansive placement outdoors in the 1970s and 1980s revolutionized the medium. Muralist Estria Miyashiro described a world before and after: “Anybody born after 1984 in a major city in the United States does not know what a city full of bare walls looks like, right? So, my generation is the last that remembers. I remember there was no such thing as murals, you know. There was just bare walls.”[i] The power of murals to advocate for grassroots concerns heightened their relevance and spurred their popularity. Murals became a social movement, forever changing the appearance of cities and towns around the globe.

In the 1970s, San Francisco’s Mission District emerged as an epicenter of mural activity. Artists saw the possibilities of murals to beautify the predominantly Latino, economically disenfranchised barrio while also depicting calls for civil rights and social justice.[ii] For Carlos Loarca, the Mission made sense as a place for artists and community organizers to gather “because we all spoke Spanish. We were all from Latin America.”[iii] Indeed, the Mission experienced a profound demographic transformation in the 1960s. As many white middle-class residents left inner city neighborhoods for the suburbs, a phenomenon known as “white flight,” working-class migrants moved into the Mission for its cheap apartments and access to employment in nearby factories. Between 1960 and 1970, the Mission District’s Hispanic population jumped from less than ten percent to about half of the neighborhood’s population.[iv] As residents built up more Spanish-language businesses and services, the Mission became known as the heart, or el corazón, of San Francisco’s Latino community.

Mission artists drew inspiration from local activism by the United Farm Workers, the Black Panther Party, and the Third World Liberation Front, as well as from transnational liberation struggles. The images varied in content and aesthetics, with some ardently anti-capitalist, anti-war, and critical of city corruption and policing, while others conveyed images of Latin American homelands, Indigenous mythologies, and heroic civil rights leaders. A variety of dynamic murals appeared on the walls of schools, community centers, apartment buildings, small businesses, nonprofits, and plyboard fences. Local organizations, including the Galería de la Raza, Neighborhood Arts Program, Precita Eyes Mural Arts, and a host of nonprofits, provided essential sponsorship, funding, training, and networks. Gradually, the Mission attracted widespread media attention and tourism for the density, artistry, and visual impact of its murals.

Above all, the community mural movement openly challenged who art was for, where it could exist, and who could be an artist. By placing art outside, muralists also subverted the exclusionary politics of art institutions. Many had firsthand experience with the elitism and racism of art schools, galleries, and museums. Circumventing barriers to entry, muralists reimagined the canvas and produced art more often in spite of the established art world than with its support.

While often disillusioned with arts institutions, many artists still appreciated the city’s abundance of historic murals, especially those created in the 1930s and 1940s with the aid of funds from the Works Progress Administration. The collection of murals at Coit Tower and in post offices, schools, and other official buildings provided a template for generations of muralists.

Strong local ties to the history of muralism in Mexico existed in the city, partly illustrated by the presence of two murals by Diego Rivera (The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City, at the California School of Fine Arts [later the San Francisco Art Institute] in 1931 and Pan American Unity at the Golden Gate International Exposition at Treasure Island in 1940). Several San Francisco muralists trained in Mexico, or with Mexican muralists, or benefitted from expert muralists who made the Bay Area their home, including Emmy Lou Packard, Stephen Pope Dimitroff, and Lucienne Bloch.

While several artists paid homage to the radical politics of this earlier period, others preferred to source popular culture, comix,[v] and everyday life in the Mission. Many artists produced dramatically different work from one mural project to the next, as was the case for Chuy Campusano, who started his mural career with Homage to Siqueiros (1974), an incendiary critique of capitalism pointed at his patron, the Bank of America, in the tradition of David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Rivera, known as “Los Tres Grandes.” The stylistic differences between this first commission and his monumental abstract work, the Lilli Ann mural (1986), is illustrative of the ways each mural project provided artists an opportunity for experimentation and diverse aesthetics.

Artists transformed bare walls into colorful, imaginative spaces, often purposefully intending to create a more beautiful and safer neighborhood. In the early 1970s, Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez turned to making murals with children in Balmy Alley as a way to make it feel safer for those same children. She also shared her paint with fellow artists Graciela Carrillo and Patricia Rodriguez, who found another wall to paint slightly further down the block. Irene Peréz joined in painting the alley, too. All of this activity gradually turned Balmy Alley into a popular destination for murals. It also marked the emergence of Las Mujeres Muralistas, a collective of women muralists, including Carrillo, Rodriguez, Pérez, and Consuelo Méndez. Women muralists often struggled with the discriminatory practices of their male counterparts. However, their mutual turn to each other as Las Mujeres Muralistas ultimately created some of the most extraordinary murals in the neighborhood.

While the art of women and children sparked change in Balmy Alley, the one-block street underwent a radical metamorphosis in 1984 when muralist Ray Patlán led a group of thirty-six muralists to protest U.S. involvement in Central America. They adopted the name “PLACA,” partly inspired by the word’s usage among neighborhood gangs to symbolically mark space with graffiti. In a group statement, they defined PLACA as “to make a mark, to leave a sign, to speak out, to have image call for response.”[vi] Their collaboration produced twenty-seven murals, turning Balmy Alley into a space replete with images protesting U.S. policies. Together, they intended to “demonstrate in visual/environmental terms, our solidarity, our respect for the people of Central America.”[vii] The event iconized communal opposition to President Reagan’s policies and conveyed spirited hopes of preventing his 1984 reelection. This was not to be; the 1980s ended with little regime change between President Ronald Reagan and President George H. W. Bush. Artists and arts organizations struggled to survive in the 1980s, as these administrations more often defunded than supported the arts. Proyecto Mission Murals carries through the Reagan years to witness this struggle for funds and support, but also to observe the ways that artists in the neighborhood joined together in community organizing and transnational solidarity struggles.

By the 1990s, muralists ventured into increasingly challenging collaborations. Maestrapeace, painted in 1994 by a team of women artists (Juana Alicia, Miranda Bergman, Edythe Boone, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton, Irene Pérez), is one example of the monumental artistry and technical prowess that Bay Area women muralists perfected over many years of mural making. The artists covered two sides of the four-story Women’s Building with a brilliantly colored, intensely detailed iconographic history of women from around the globe. Maestrapeace points to the ways the community mural movement had evolved in scale and technique.

This era also saw the beginnings of the tech boom’s impact on the Mission. As tech workers migrated from Silicon Valley to San Francisco, the Mission emerged as a desirable destination. In the 1990s, the rapidness of gentrification challenged the capacity of artists and other low-income residents to stay in the Mission, which also dramatically reshaped the area’s cultural production. Many artists personally experienced this evolving economic destabilization in the form of rent increases and questionable real estate gambits, leading them to center displacement as a pivotal concern in the art.

While these stresses unfolded, a new generation of artists started to gain visibility for their contributions to the neighborhood’s mural movement. Inspired by Balmy Alley, this loose collective of artists gathered to paint Clarion Alley in 1992. This, however, gradually posed a complex art historical problem, as Clarion Alley captured the attention of arts institutions in a way that never shined on Balmy Alley, Maestrapeace, or the preceding decades of Mission muralism. Indeed, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and a variety of arts institutions heralded Clarion Alley and this new generation of artists as “The Mission School,” taking the moniker of the neighborhood while also excluding many years of artistic activity.

In some respects, Proyecto Mission Murals tackles this erasure by focusing on earlier years of cultural production, though this dividing line is ultimately quite porous. Many of the younger artists working in the Mission acknowledged and relied on the expertise of the long-standing arts community. Nonetheless, the institutional anointing of “The Mission School” underscores the complexities of documenting the origins of the community mural movement in San Francisco’s Mission District with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. This digital humanities project represents a starting point for recognizing the tremendous artistic activity that has shaped the Mission District and contributed to the richness of the community mural movement around the globe.

Notes

- Oral history interview with Estria Miyashiro conducted by Camilo Garzón on July 13, 2021, for Proyecto Mission Murals.

- For more on the cultural and artistic transformation of the Mission, see Cary Cordova, The Heart of the Mission: Latino Art and Politics in San Francisco (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017). The use of the term “Latino” is imperfect. As Eduardo Contreras writes, “Latinos is linguistically gendered and an imperfect way to classify a population composed of women, men, and individuals who may have identified otherwise.” Like Contreras, I use Latino in keeping with a twentieth-century focus, while also pointing to the importance of engaging with “gender inclusivity and fluidity.” See Contreras, Latinos and the Liberal City: Politics and Protest in San Francisco (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), 14. This project uses Latino, Latina, Chicano, and Chicana as historical terms reflective of the period, while also applying Latinx and Chicanx as inclusive contemporary terms. Drawing on the writing of Richard T. Rodríguez, this project aspires “to champion the X as drawing attention to and not overshadowing nonbinary and gender neutral and nonconforming individuals.” See Rodríguez, “X marks the spot,” Cultural Dynamics 29, no. 3 (2017), 202–13.

- Oral history interview with Carlos Loarca conducted by Cary Cordova in 2003 for The Heart of the Mission.

- Cordova, Heart of the Mission, 67. As the census has a history of undercounting Latinos, concrete statistics are difficult to establish. See Julie Dowling, Mexican Americans and the Question of Race (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

- Comix refers to a rebellious subculture of the comics industry that redefined the possibilities of the artform in the 1970s. See Patrick Rosenkranz, Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution (Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2008).

- “Placa,” Community Murals Magazine, Fall 1984, 10.

- Ibid.

Murals

The images of and object information provided for the murals published here are drawn from the book San Francisco Bay Area Murals: Communities Create Their Muses 1904–1997 by Timothy Drescher, first published in 1987 by Pogo Press. Object information was reviewed where possible, and updated as relevant, by the muralists for the context of this project. SFMOMA welcomes any additional updates or corrections to the information presented here.

-

George Mead

*[Silhouette Mandala]

1976 -

Michael Ríos

*MCO (Mission Coalition Organization)

1972 -

Bob Cuff, Jésus "Chuy" Campusano, Rubén Guzmán, and Spain Rodriguez

*Horizons Unlimited

1972 -

Patricia Rodriguez and Graciela Carrillo

*Untitled

1972 -

Patricia Rodriguez, Jésus "Chuy" Campusano, Rubén Guzmán, Consuelo Méndez, Jerome Pasias, Elizabeth Raz, and Tom Rios

[Jamestown Mural]

1973 -

Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez and children from 24th St. Place

*Untitled

1973 -

Bob Cuff, Jésus "Chuy" Campusano, Gerald Concha, Robert Crumb, and Rubén Guzmán

*Mission Rebels

1973 -

Irene Pérez

Flute Players

1973 -

Graciela Carrillo and Patricia Rodriguez

[Tree with Animals]

1973 -

Mujeres Muralistas: Graciela Carrillo, Consuelo Méndez, Susan Kelk Cervantes, and Miriam Olivas

*Para el Mercado

1974 -

Michael Ríos, Anthony "Tony" Machado, and Richard Montez

*[Quetzalcoatl]

1974 -

Susan Kelk Cervantes, Ray Rios, Maria Brecker, Maria Juarequi, Dialo Seitu, Judy Jamerson, Edith Jeffries, and many others

*A Day in the Life of Precita Valley

1974 -

Mujeres Muralistas: Patricia Rodriguez, Graciela Carrillo, Consuelo Méndez, Irene Pérez, Ruth Rodríguez, Miriam Olivas, Ester Hernández, and Xochitl Nevel-Guerrero

*Latino America

1974 -

Jésus "Chuy" Campusano, Luís Cortázar, and Michael Ríos

[Homage To Siqueiros]

1974 -

Tomas Belsky, Bob Primus, and and others

*My 'Tis Of Thee. . .

1974 -

Michael Ríos, Anthony "Tony" Machado, and Richard Montez

BART

1975 -

Michael Ríos

*Vietnamese

1975 -

Michael Ríos, Anthony "Tony" Machado, and Richard Montez

*Untitled

1975 -

Susan Kelk Cervantes, Patricia Rodriguez, Frances Valesco, and Neighborhood Youth Corps

*Kool Blue

1975 -

Graciela Carrillo, Patricia Rodriguez, and Neighborhood Youth Corps

*Untitled

1975 -

Domingo Rivera

*Psycho-Cybernetics

1975 -

Jack Frost

*[Hot Air Balloons Above Bryce Canyon]

1975 -

Domingo Rivera

[Aztec Spaceship]

1975 -

Mujeres Muralistas: Graciela Carrillo, Irene Pérez, and Patricia Rodriguez

Fantasy World for Children

1975 -

Domingo Rivera

*[CIA Diary]

1975 -

Gerald Concha

*No somos hippos plásticos

1975 -

Gilberto Ramírez

*LULAC Mural

1975 -

George Mead

*[Worldview]

1976 -

Michael Ríos

Mission Neighborhood Health Center

1976 -

Michael Ríos, Graciela Carrillo, Sekio Fuapopo, Patricia Rodriguez, Frances Valesco, and Neighborhood Youth Corps

*Untitled

1976 -

Michael Ríos and Anthony "Tony" Machado

*¡Esta gran humanidad ha dicho basta! / This Great People Has Said Enough!

1976 -

City Muralists

*[Untitled]

1976 -

Gary McGill

*When the Buffalo Were on the Mountains

1976 -

James Dong and Nancy Hom

*The Struggle for Low-Income Housing

1976 -

Graciela Carrillo

Humanidad

1976 -

Susan Kelk Cervantes, Judy Jamerson, Tony Parrinello, Maurice Lacy, Robert Junti, Karlos DeMille, Joe Fradella, Frank Fradella, and mural workshop volunteers

Family Life and Spirit of Mankind

1977 -

Susan Kelk Cervantes, Judy Jamerson, and mural workshop volunteers

Four Seasons of Life

1977 -

Michael Ríos

San Francisco Community Law Collective

1977 -

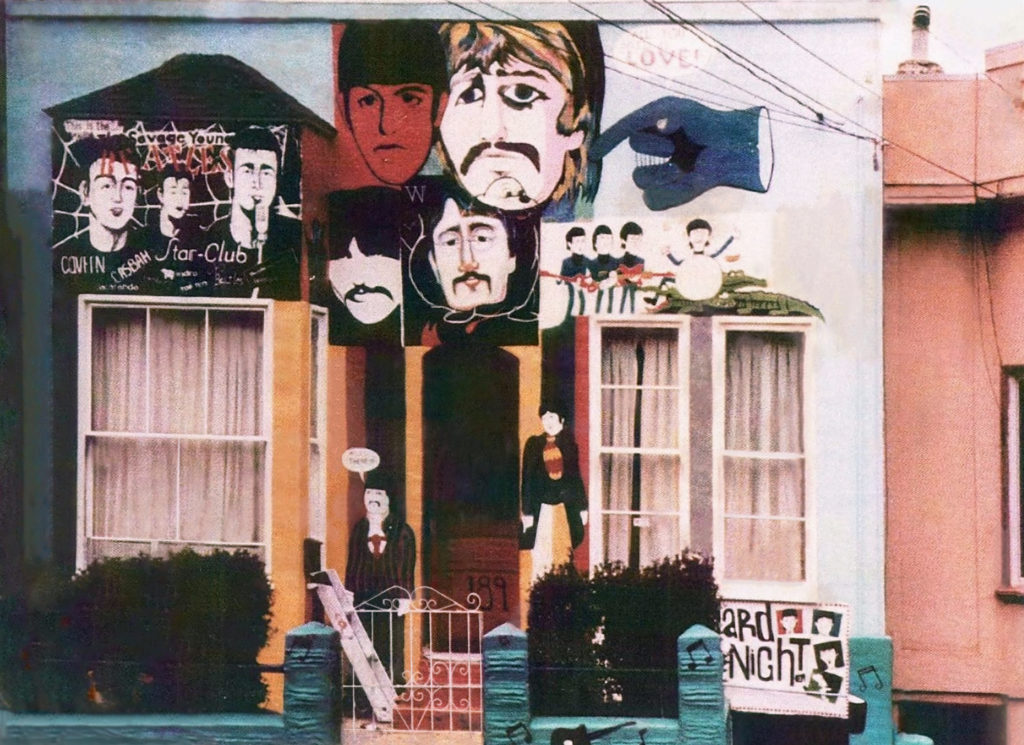

Jane Weems

*The Beatles

1977 -

Scarlett Manning

*Let There Be Light

1977 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Susan Kelk Cervantes, Tony Parrinello, Judy Jamerson, Margo Consuela Bors, Karen Magnusen, Star Carroll-Smith, Thomas Gaviola, Beatrice Spiegel, Joe Gomez, Pete Anoa'i, and Denise Mehan

*Masks of God/Soul of Man

1978 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Denise Mehan, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Tony Parrinello, Margo Consuela Bors, José Gómez, Kathryn Brousse, Thomas Gaviola, S. McViker, Pete Anoa'i, and China Books Staff

A Bountiful Harvest

1978 -

Carlos Loarca, Alvarado School Arts Program, Juanita Brand, Jaime Gomez, Jose Gutierrez, Maria Gomez, Dolores Miazzo, and Fernando Picazo

Homage to Woman

1978 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Kit Davenport, Pat Stallings, Denise Mehan, Judy Jamerson, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Barbara Kosman, Greg Edwards, Thomas Gaviola, and Star Carroll-Smith

*Every Child Is Born to Be a Flower

1979 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Tony Parrinello, Margo Consuela Bors, Basil Brummel, Jeanne Babette, Karin Schlesinger, Beatrice Spiegel, Luis Cervantes, and Joe Gomez

*Reflections

1979 -

Brigada Orlando Letelier

*Casa Sandino

1979 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Susan Kelk Cervantes, Denise Mehan, Pete Anoa'i, Star Carroll-Smith, Tony Parrinello, Nina Eliasoph, and Joe Gomez

The Primal Sea

1980 -

Judy Jamerson and Mission High School students

*[Students with Lamp of Knowledge]

1981 -

Judy Jamerson and students

*[Mission District Silhouettes]

1981 -

Johanna Poethig, Selma Brown, Claire Josephson, Kathleen Bucklew, Ariella Seidenberg, and Deborah Greene

Out of the Closet

1981 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Kit Davenport, Karin Schlesinger, and Judy Jamerson

*Suaro’s Dream

1982 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Patricia Rose, Beatrice Spiegel, Carlos del Valle, Margo Consuela Bors, and Luis Cervantes

*The Unicorn's Dream

1982 -

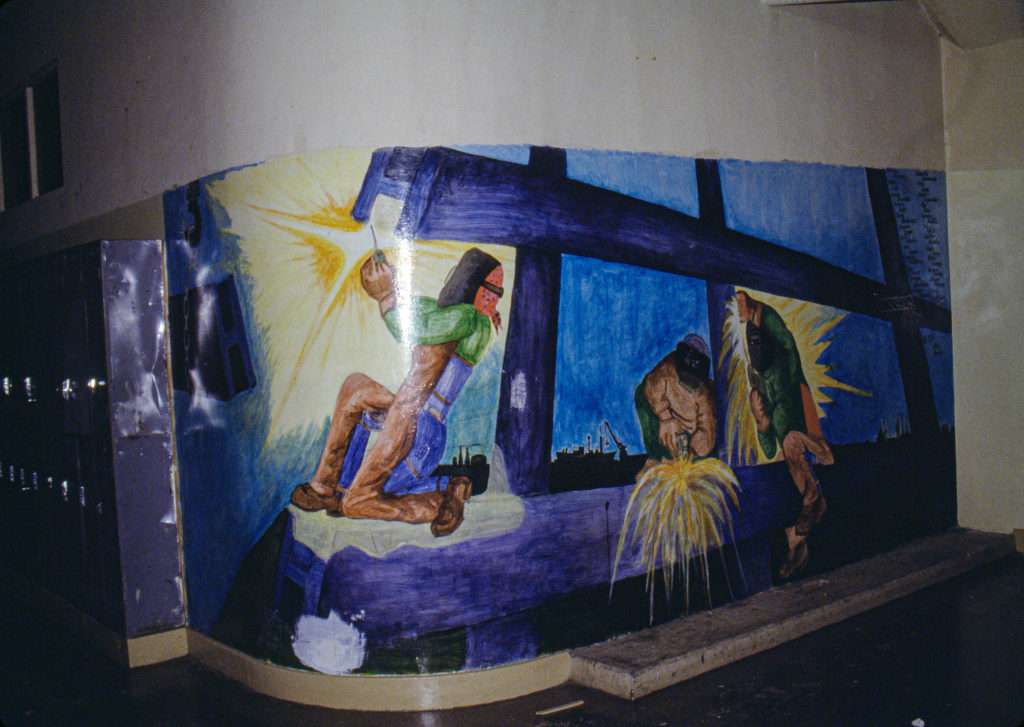

Victoria Hamlin and students

Wonder Welders

1982 -

Frances Valesco

*Desert

1982 -

Michael Ríos

*ABC

1982 -

Patricia Rodriguez, Francis Stevens, Miranda Bergman, Nicole Emanuel, and Celeste Snealand

*Women’s Contribution

1982 -

Michael Ríos

[Children Dance around The World]

1982 -

Claire Josephson and Monica Armstrong

Dreamer’s Gaze

1982 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Luis Cervantes, and Susan Kelk Cervantes

*Celestial Cycles

1982 -

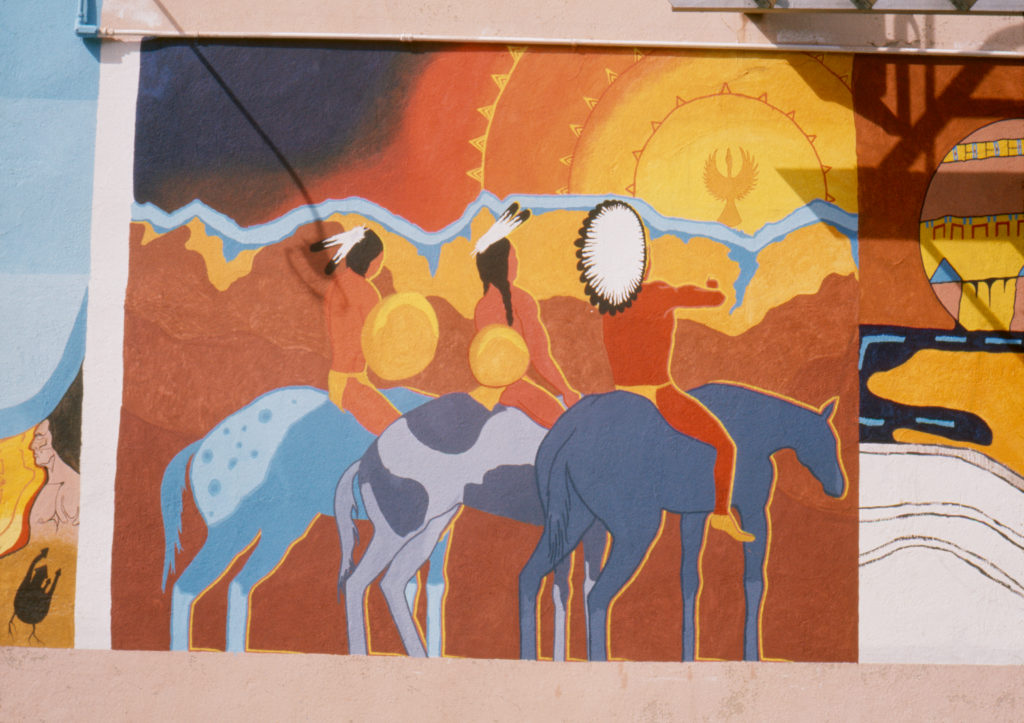

Carlos Loarca, Manuel Villamor, and Betsie Miller-Kusz

[Native American Mexicans]

1982 -

Ray Patlán and playground youth

*Barrio Folsom

1982 -

Mike Mosher

*The Mission Reds at Woodward’s Gardens

1982 -

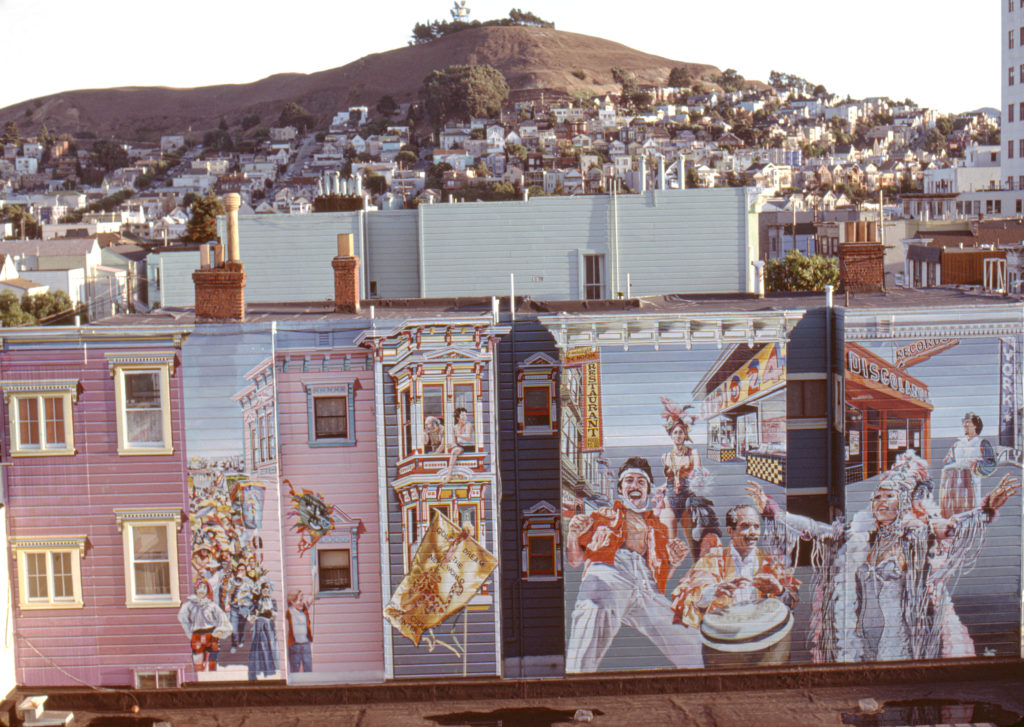

Daniel Galvez, with Dan Fontes, James Morgan, Jan Shield, and Keith Sklar

Carnaval

1983 -

Emmanuel Montoya, Ben Morales-Correa, and Noel Santiago

*Untitled

1983 -

Nicole Emanuel, Nicole George, and Patricia Rodriguez

*Culture Of Nicaragua

1983 -

Susan Kelk Cervantes and the Precita Eyes Muralists

*Sierra Queen

1983 -

PLACA: Keith Sklar

*For Central America / Para Centroamérica

1984 -

PLACA: Juana Alicia

*Te Oímos Guatemala / We Hear You Guatemala

1984 -

PLACA: Susan Kelk Cervantes

*A Dream of Death Falling, Spirit Rising: Peace to Central America / Un sueño en el que la muerte cae y el espíritu se levanta: Paz para Centroamérica

1984 -

PLACA: Frances Valesco

The Contest between the Sun and the Wind / El torneo entre el sol y el viento

1984 -

PLACA: Jane Norling

*Give Them Arms and Also Teach Them How to Read / Dadles armas y también enseñadles a leer

1984 -

Precita Eyes Muralists: Susan Kelk Cervantes, Kit Davenport, Tony Parrinello, and Patricia Rose

A Vision of America at Peace

1984 -

PLACA: Raymundo "Zala" Nevel

*Honor the American Indians / Honra a los indios americanos

1984 -

PLACA: Ray Patlán and Francisco Camplís

*On the Way to the Market / Camino al mercado

1984 -

PLACA: Carlos "Kookie" Gonzalez and Julian “Jueboy” Torres

*Keeping the Peace (in Central America) / Preservando la paz (en Centroamérica)

1984 -

PLACA: Osha Neumann

*Regeneration / Regeneración

1984 -

PLACA: Nicole Emanuel

*Indigenous Beauty / Belleza indígena

1984 -

PLACA: Eduardo Pineda

*Power Play / Juegos de poder

1984 -

PLACA: Brooke Fancher

*My Child Has Never Seen His Father / Vuelan lejos los sentimientos cuando los amados han muertos todos

1984 -

PLACA: Kriska Boiral

*Waves / Ondas

1984 -

PLACA: Carl Araiza

*The Voice of Music / La voz de la música

1984 -

PLACA: Randall Bronner, and Jim Lewis

*To Three Nuns and a Layperson / Para tres monjas y una mujer secular

1984 -

PLACA: Herbert Sigüenza

*After the Triumph / Después del triunfo

1984 -

PLACA: Susan Greene

*Woven Masks / Máscaras tejidas

1984 -

PLACA: Crystal Nevel and Xochitl Nevel-Guerrero

*Youth of the World, Let's Create a Better World / Juventud del mundo, vamos a crear un mundo mejor

1984 -

PLACA: Terry Brackenbury, Gary Crittendon, and Marsha Poole

*Untitled

1984 -

PLACA: Miranda Bergman and O'Brien Thiele

Culture Contains the Seed of Resistance Which Blossoms into the Flower of Liberation / La cultura contiene la semilla de la resistencia que se convierte en la flor de la liberación

1984 -

PLACA: Wendy Miller, Marsha Ercegovic, Michele Tavernite, and Janet Storm

*New Un-improved Wash ‘N’ War/Nuevecito sin mejoramiento la ropa de guerra

1984 -

PLACA: Patricia Rodriguez

*The Resurrection of the Conquest / La resurrección de la Conquista

1984 -

PLACA: Jose Mesa

*United In The Struggle/Unidos en la lucha

1984 -

PLACA: Roberto Guerrero

*Guerra, Incorporated

1984 -

Ray Patlán and Carlos "Kookie" Gonzalez

*Y tú, y yo y qué

1984 -

Juana Alicia

For the Roses / Pa’ las rosas

1985 -

Juana Alicia

*The Women Lettuce Workers / Las Lechugueras

1985 -

Michelle Irwin and Rita Luisa Bairley

Untitled

1985 -

Patricia Rose

Harvest

1985 -

Juana Alicia, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Raul Martinez, Emmanuel Montoya, Robert Chavarria, Daniel Socarras, Frank Cortez, Roberto Méndez, Irma Campos, Scott Brown, Damien Contrerras, Filberto Fuentes, Cathy Ross, Linda Fields, and Mike Mosher

Balance of Power

1985 -

Susan Greene and Pedro Oliveri

Socialist Bookstore

1985 -

Susan Kelk Cervantes

Our Children Are Our Only Reincarnation

1985 -

Susan Greene, Jane Norling, Eduardo Pineda, Eddie Hippley, Vincent Jackson, Melody Lima, Michael Bernard Loggins, and Cam Quach

*New Visions by Disabled Artists

1986 -

Juana Alicia and students Bob Thawley, Silvia Soriano, et al.

*Murals for La Raza Graphics

1986 -

Jésus "Chuy" Campusano, Elias Rocha, Samuel Dueñas, Roger Rocha, Carlos Anaya, and Signpainters Local 510

*Lilli Ann

1986 -

Jo Tucker

Gardens Of Healing

1986 -

Juana Alicia, Susan Kelk Cervantes, and Raul Martinez

New World Tree

1987 -

Michael Ríos

El faro de San Francisco y la Mission

1987 -

Michael Ríos, Carlos "Kookie" Gonzalez, and Johnny Mayorga

*Inspire to Aspire: Tribute to Carlos Santana

1987 -

Juana Alicia

*Alto al fuego / Ceasefire

1988 -

Eduardo Pineda, Jim Valdez, Eddie Hippley, Michael Bernard Loggins, and and Mr. Margolis

Retablo of Parents / Retablo de los padres

1988 -

Mariano Paredes

*[Aztec, Early California, and Cosmic History]

1988

Biographies

Artists

-

not available

Juana Alicia

-

not available

Miranda Bergman

-

not available

Jésus "Chuy" Campusano

-

not available

Graciela Carrillo

-

not available

Luis Cervantes

-

not available

Susan Kelk Cervantes

-

not available

Dewey Crumpler

-

not available

Nicole Emanuel

-

not available

Daniel Galvez

-

not available

Carlos "Kookie" Gonzalez

-

not available

Nancy "Pili" Hernández

-

not available

Carlos Loarca

-

not available

Yolanda López

-

not available

Anthony "Tony" Machado

-

not available

Consuelo Méndez

-

not available

Xochitl Nevel-Guerrero

-

not available

Ray Patlán

-

not available

Irene Pérez

-

not available

Eduardo Pineda

-

not available

Michael Ríos

-

not available

Patricia Rodriguez

-

not available

Patricia Rose

-

not available

Herbert Sigüenza

-

not available

Frances Valesco

Documentary

Interviews

-

Amalia Mesa-Bains Oral History

This is an oral history interview of curator, critic, author, visual artist, and educator Amalia Mesa-Bains. She reflects upon her interactions with Mujeres Muralistas, her work as arts commissioner, her MacArthur Foundation fellowship, and her partnership and life with her husband, Richard, and the influence of her friendships with Luis Valdez and Ralph Maradiaga.

This oral history is only available as a downloadable transcript.

-

Brooke Oliver Oral History

This is an oral history interview of lawyer Brooke Oliver. She reflects on how her law career placed her at the forefront of visual arts legislation in the United States and discusses the cases she has defended in front of the Supreme Court; her law practice; and social justice issues related to race, sexual orientation, and gender expression.

-

Carlos "Kookie" Gonzalez Oral History

This is an oral history interview of muralist and artist Carlos “Kookie” Gonzalez. He delves into his career as an artist and probation officer, and also talks about his friendship and work with muralists Susan Kelk Cervantes, Michael Ríos, and Ray Patlán. Gonzalez describes the importance of music in his life and his current projects after retirement.

-

Consuelo Méndez Oral History

This oral history explores Méndez’s early life in Venezuela, her upbringing in the United States, her relationship with her parents, her work shaping and creating art as one of the founders of the legendary art collective Las Mujeres Muralistas, and her role in preserving and amplifying Latino heritage in San Francisco’s Mission District, in Venezuela, and elsewhere.

This oral history interview was conducted in Spanish, but the transcript has been translated to English.

-

Daniel Galvez Oral History

In this oral history interview of muralist and artist Daniel Galvez, the artist details the public art he generated and activism he participated in throughout the years. Galvez reflects on his role in preserving and amplifying his Chicano heritage and carving out his own legacy through the arts.

-

Dewey Crumpler Oral History

This is an oral history interview of Dewey Crumpler, muralist, artist, and educator. Dewey reflects on his early life and trips he took to his native Arkansas while growing up, witnessing the erasure of Black history from his education, and discussing how that motivated him to create art that examines racism in the United States.

-

Eduardo Pineda Oral History

This is an oral history interview of Peruvian American artist, educator, and curator Eduardo Pineda. In addition to describing the public art he has generated through the years, Pineda discusses his early life in Peru, his work in the visual arts world, and his educational projects, as well as his curatorial assignments.

-

Ester Hernández Oral History

This is an oral history interview of visual artist Ester Hernández. She delves into her Mexican and Yaqui roots, her rural upbringing, and her work as a muralist, visual artist, and educator. Hernández also reflects on the influence of Japan in her work and her time with the Mujeres Muralistas.

-

Estria Miyashiro Oral History

This oral history delves into Miyashiro’s personal life and his work as an artist. He shares his experience of moving from Hawaii to San Francisco, his initial interest in mural making, and what he learned from other artists. He discusses the expanse of public art and activism he generated throughout the years, his role in preserving and amplifying his own Hawaiian heritage, and how he carved out his own legacy through the arts.

-

Frances Valesco Oral History

This is an oral history interview of artist and educator Frances Valesco. Valesco delves into her personal life and upbringing and goes into her work as a muralist and educator, especially related to her past and present work on the Disability Mural. She also discusses her teaching life and her current doctorate.

-

Irene Pérez Oral History

This is an oral history interview of Irene Pérez, visual artist and founding member of Mujeres Muralistas. Pérez discusses her early life in the East Bay, her work in forming and creating art as a founding member of the collective, identifying as lesbiana, and the important role Mexico plays in the imagery of her work.

-

Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez and Ana Montano Oral History

This oral history interview delves into the facets of art educator Gonzalez’s and lawyer Montano’s early lives and their upbringings. They also speak of their personal and political reasons for establishing Balmy Alley as an arts space. Gonzalez and Montano also reflect on their roles in preserving and amplifying Chicanx and Latinx heritage in San Francisco and beyond.

-

Michael Ríos Oral History

In this oral history interview of pivotal Chicanx artist Michael Ríos, the personal and political reasons for Ríos’s focus on muralism are clarified as he takes us, mural by mural, on a journey through the expanse of public art he has generated throughout the years.

-

Nancy "Pili" Hernández Oral History

This is an oral history interview with artist and activist Nancy “Pili” Hernández. She details her foray into murals and street art and also discusses her more recent work as an activist, especially related to her activism with the Resist banner in Washington, DC, after the 2016 US presidential election.

-

Patricia Rodriguez Oral History

This is an oral history interview of muralist and educator Patricia Rodriguez. She talks about the beginnings of Mujeres Muralistas, her depictions of everyday women and people from the community in her murals, and her role in preserving and amplifying Chicanx and Latinx heritage in San Francisco’s Mission District and beyond.

-

Ray Patlán Oral History

In this oral history interview, Ray Patlán, Chicanx artist, educator, and cofounder of PLACA, delves into his early life in Chicago that led to his career as an artist, including his trips to México since he was a kid, and details his foray into visual art, his educational projects, as well as his teaching life.

-

Susan Kelk Cervantes Oral History

This is an oral history interview of Susan Kelk Cervantes—muralist, artist, and cofounder of Precita Eyes Muralists. The artist describes her childhood in Texas and details her participation in Mujeres Muralistas, as well as her creative collaborations with her late husband, artist Luis Cervantes, and lifelong dedication to sharing mural making with current and future generations.

-

Tim Drescher Oral History

This is an oral history interview of independent scholar Tim Drescher. He discusses his deep engagement in the community mural movement in San Francisco beginning in the 1970s, including his experiences working directly with muralists in various capacities and his role in studying and documenting murals through photography and participation in publications including Community Murals.

This oral history is only available as a downloadable transcript.

-

Xochitl Nevel-Guerrero Oral History

This is an oral history interview of muralist, artist, and educator Xochitl Nevel-Guerrero. She discusses her work in the Nosotros venceremos mural and her collaboration with the Mujeres Muralistas, including her work on the MAESTRAPEACE mural in San Francisco’s Women’s Building. Nevel-Guerrero also expands on her role in helping preserve and amplify Chicanx and Latinx heritage in the Bay Area and beyond.

-

Yolanda López Oral History

In this oral history interview, Chicana artist and activist Yolanda López reflects on what led to her career as an artist and reviews the expanse of public art she generated throughout the years. She also details her work as an activist, especially related to Chicano Park and Los Siete.

Essays

-

Mapping Origins: Mural Activism in the Mission

September 2022

Cary Cordova

-

Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts: Recovering a Conceptual Mission Mural

September 2022

Ella Maria Diaz

-

Central American Solidarity Murals of the Mission District

September 2022

Mauricio Ramirez

-

Mujeres Muralistas: Pictorializing Latinoamérica in the Mission

September 2022

Terezita Romo

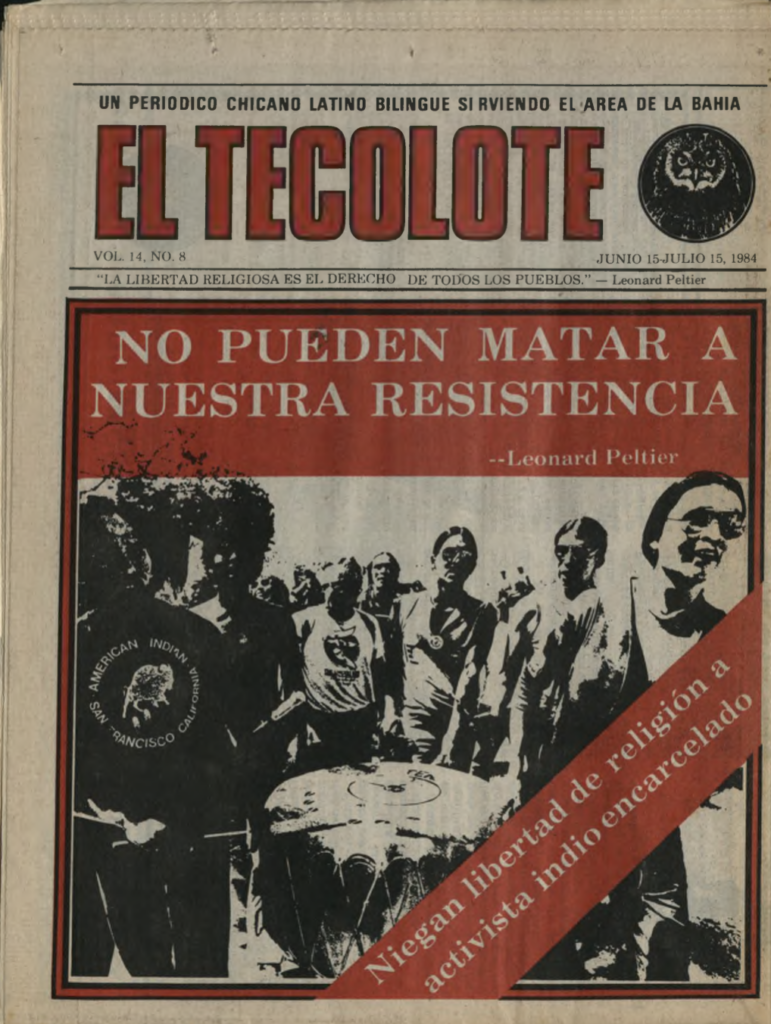

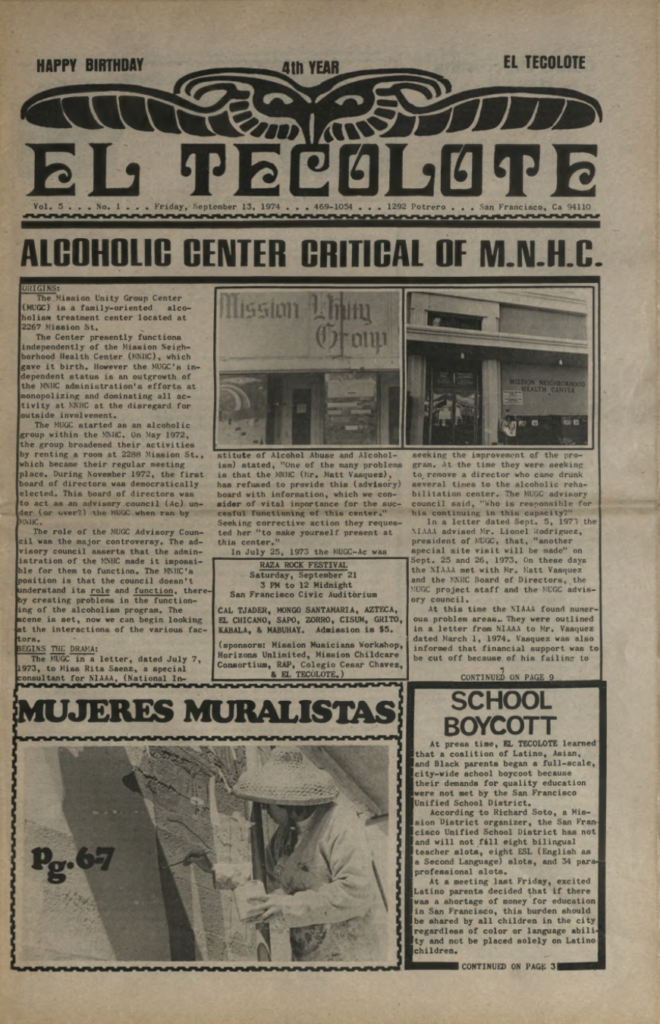

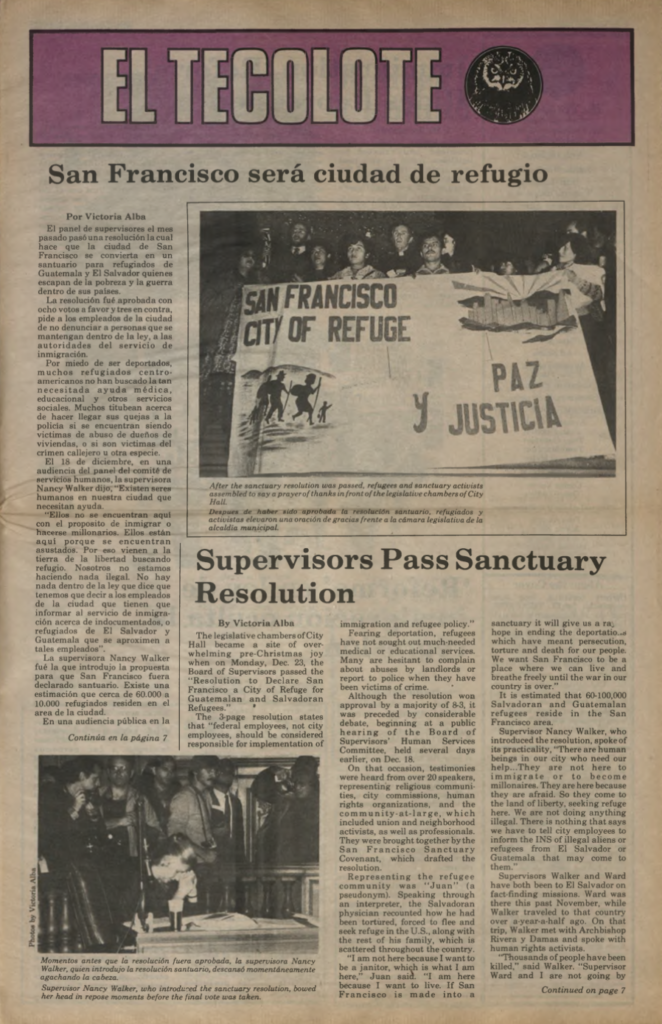

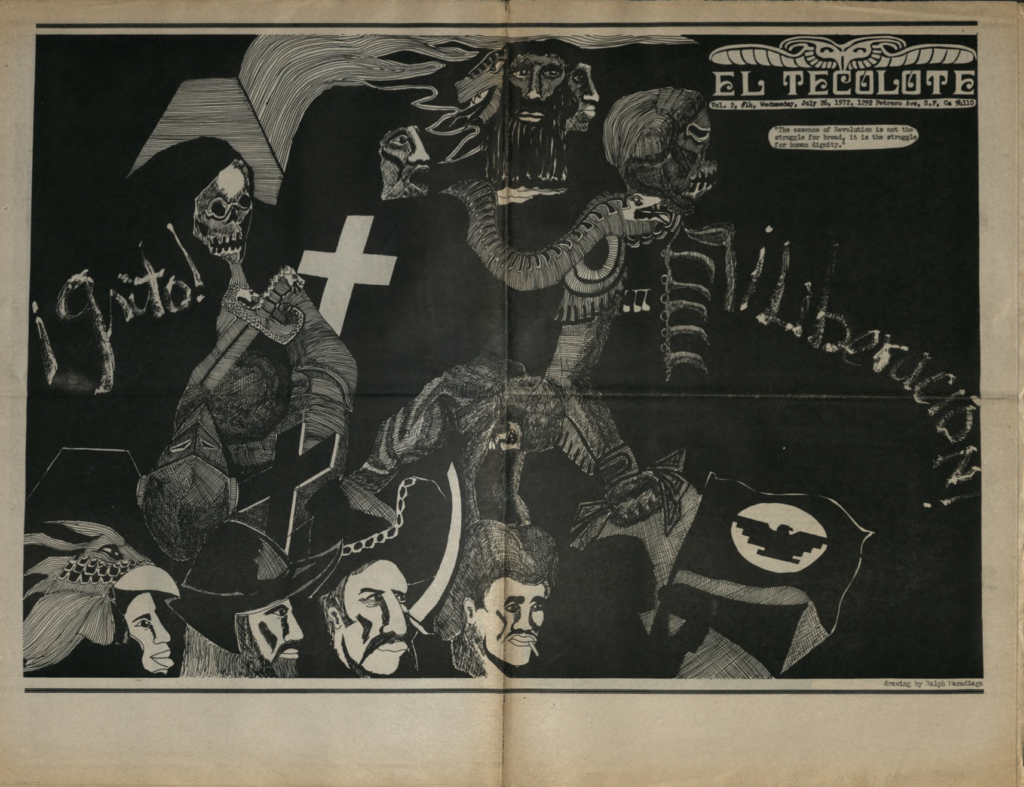

El Tecolote

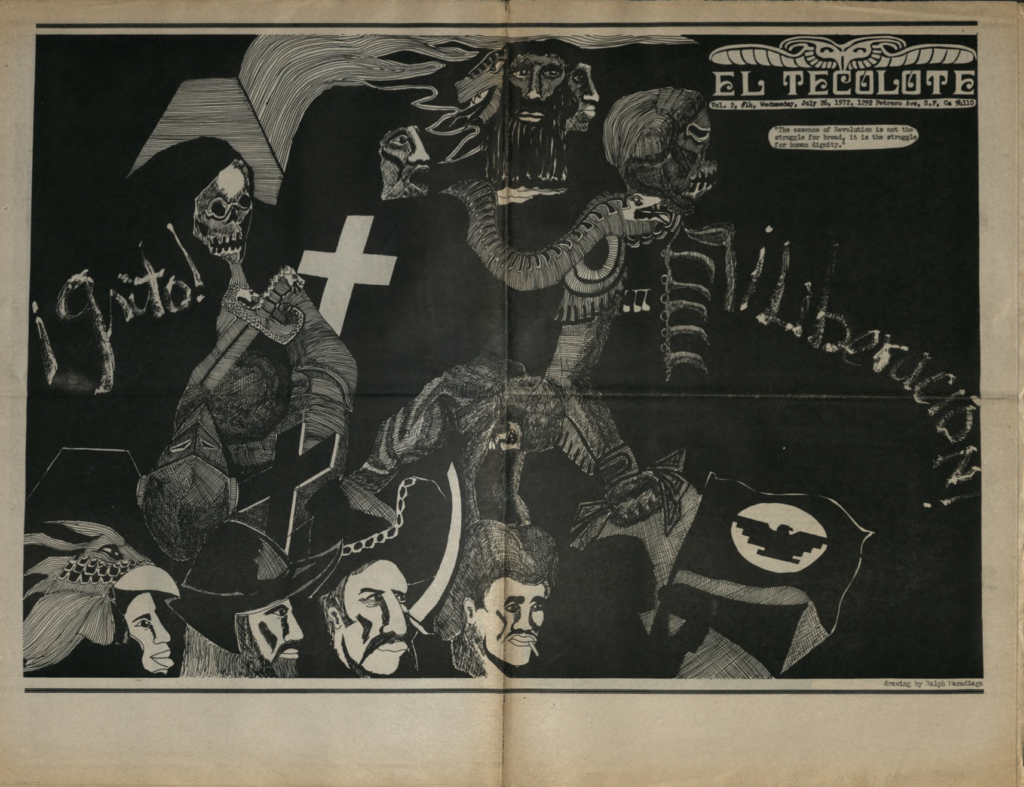

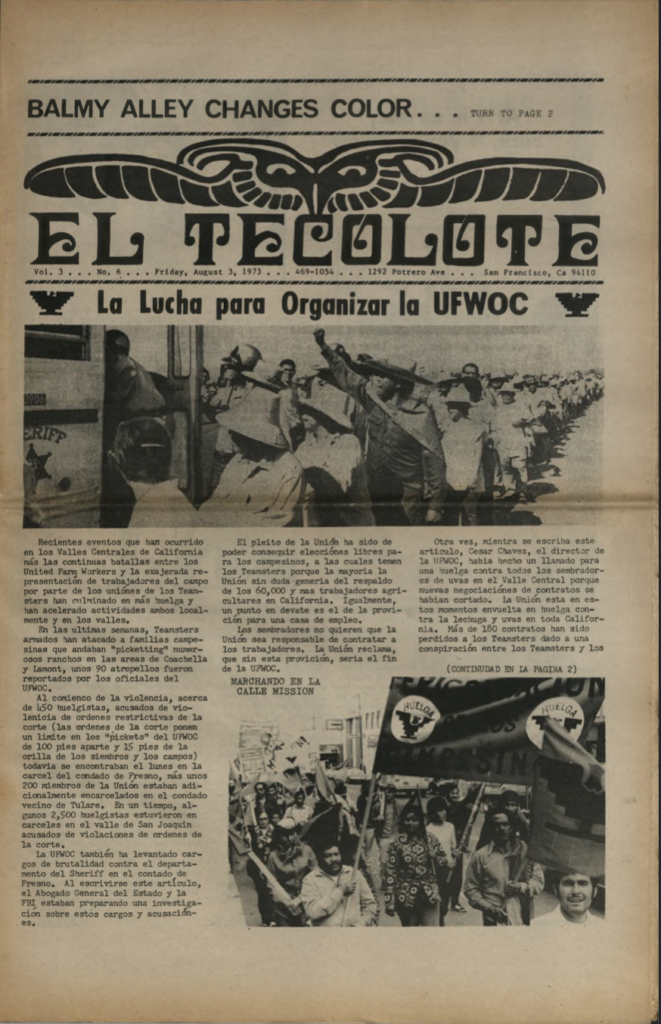

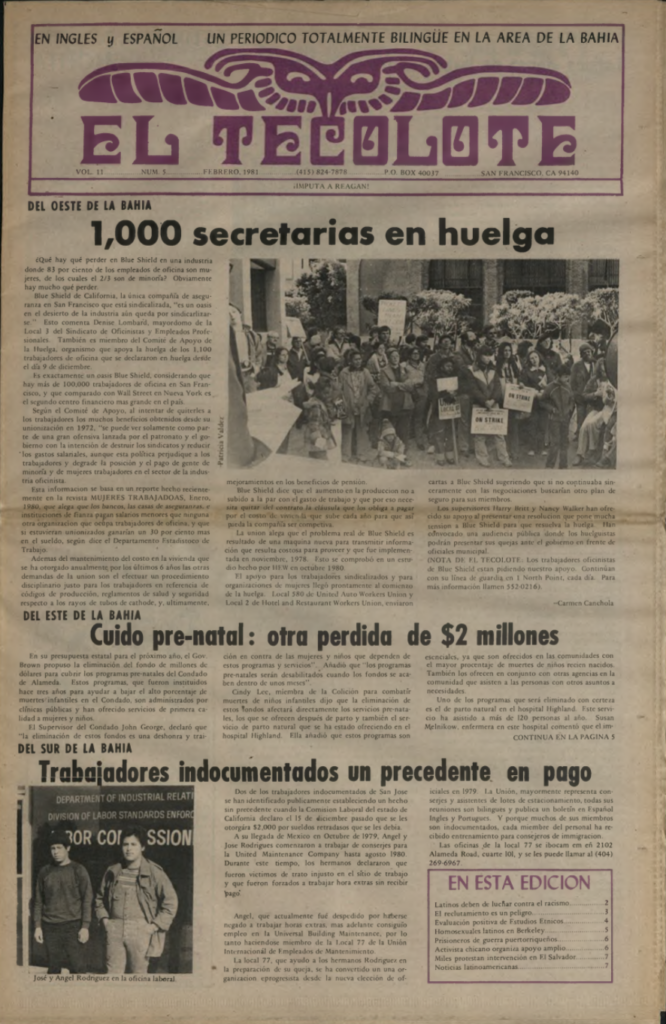

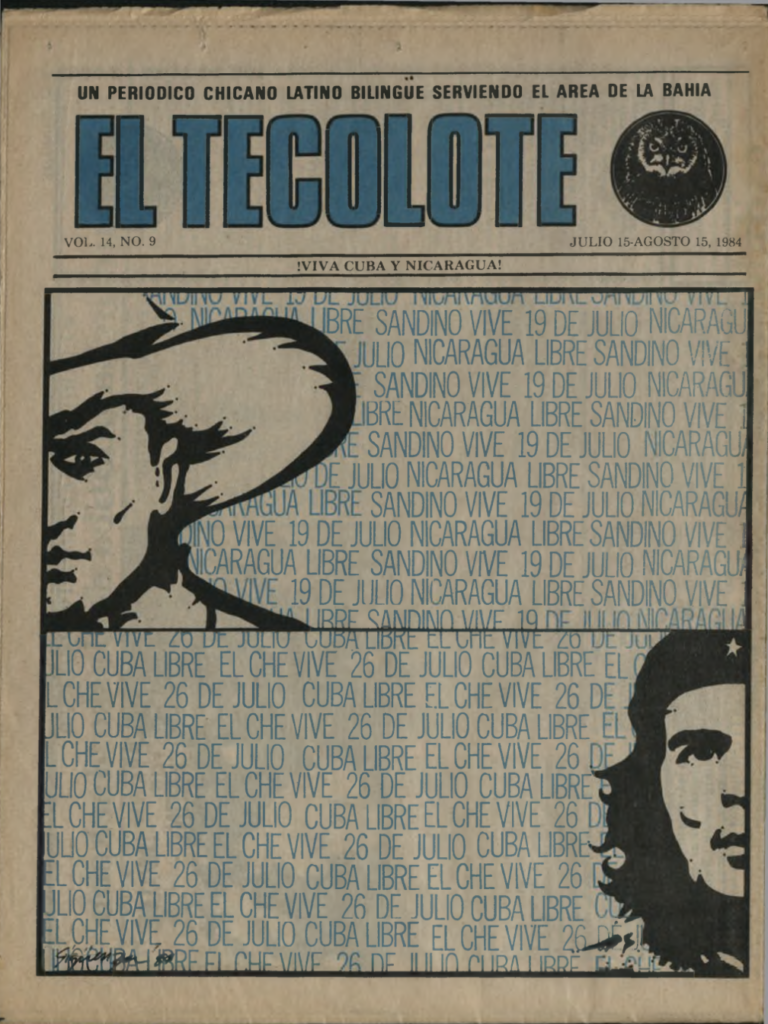

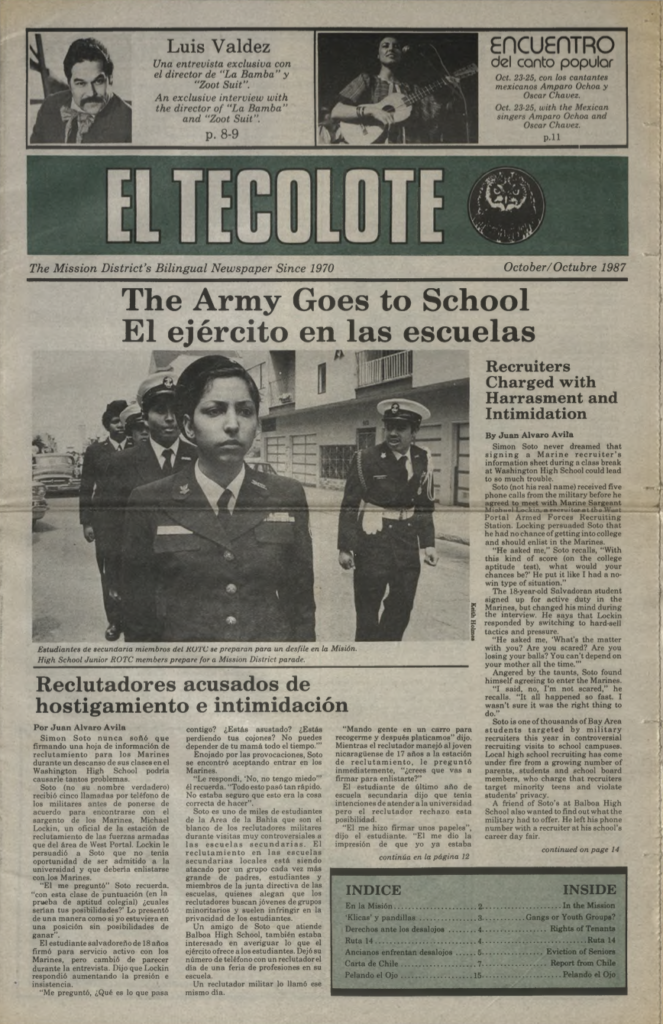

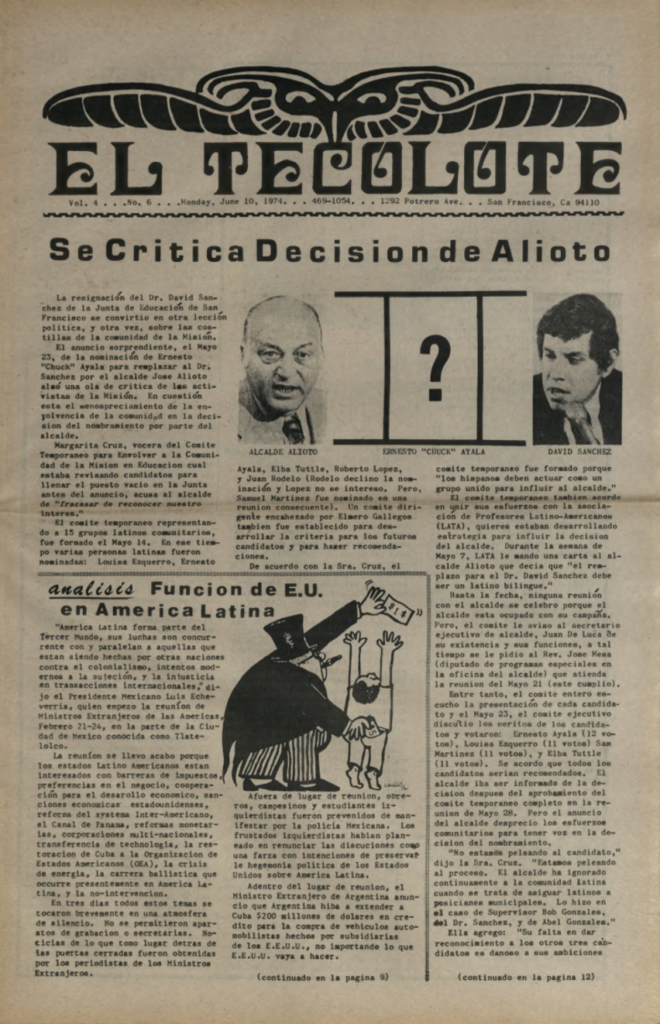

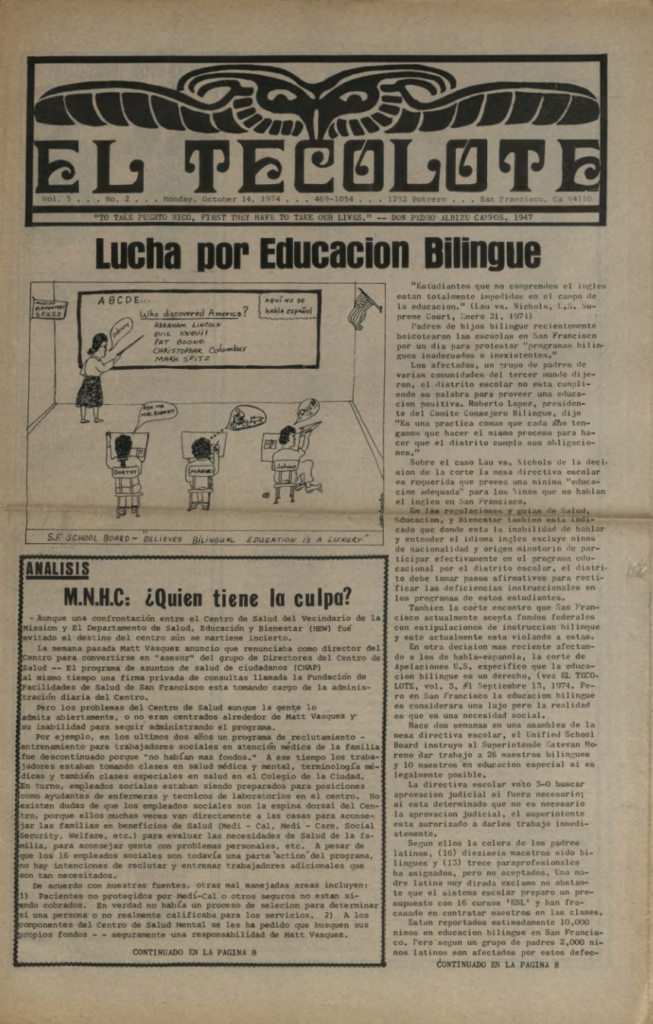

El Tecolote is the longest running Spanish/English newspaper in California. It was founded in 1970 by San Francisco State University La Raza Studies Professor Juan Gonzalez and continues to be published and distributed by Acción Latina. The newspaper addresses regional, national, and international issues affecting Latino communities in the Bay Area and beyond. A full archive of issues of El Tecolote is available as part of the Acción Latina archive.

The importance of El Tecolote in documenting the history of the Mission District, and the arts in particular, cannot be overstated. While the San Francisco Chronicle and the San Francisco Examiner offered occasional neighborhood reports, El Tecolote provided bilingual reports on key issues impacting the Mission, including policing, education, housing, city services, and the arts. The publication regularly featured the work of local artists, with articles by Rupert Garcia and illustrations by Juan Fuentes, René Yañez, and Yolanda Lopez. Ralph Maradiaga created the first masthead for the publication in the form of an almighty owl with wings stretched, provided occasional illustrations and comic strips, and produced a short film about the newspaper.

https://californiarevealed.org/islandora/object/cavpp%3A13833

El Tecolote covered the opening of Galería de la Raza, the creation of the Mission Cultural Center, the release of films by Mission filmmakers, and occasional reports on new murals and emerging muralists. The paper regularly incorporated poetry, photography, sketches, and illustrations. Melissa San Miguel gathered this select group of articles that spotlight the emerging mural movement in the Mission within the period of time covered by Proyecto Mission Murals. Cary Cordova wrote the accompanying text.

-

“A Historical Look at Raza Murals and Muralists”

El Tecolote 2, no. 14

July 26, 1972

Rupert Garcia

-

“Arts in an alley? Sure, if you’re Balmy”

El Tecolote 3, no. 6

August 3, 1973

Photos by Martha Estrella

-

“The Newest in Mission Murals”

El Tecolote 6, no. 4

January 1976

Photos by Francisco Garcia

-

”Pulquería Art: Defiant Art of the Barrio”

El Tecolote 8, no. 4

December 1977

Rupert Garcia

-

"Pulquería Art: Defiant Art of the Barrios”

El Tecolote 8, no. 5

February 1978

Rupert Garcia

-

“Arts & Culture: Local Artists Exhibit Their Work”

El Tecolote 13, no. 5

February 1981

Herbert Sigüenza

-

“Murals portray U.S. intervention in C.A.”

El Tecolote 14, no. 9

July 15–August 15, 1984

Sabrina Hernandez

-

“Local Artists Receive Grants”

El Tecolote

October 1987

-

"This mural is not for the bankers. It’s for the PEOPLE."

El Tecolote 4, no. 6

June 10, 1974

Rupert Garcia covers mural by Chuy Campusano

-

"Mission Muralist off to Mexico"

El Tecolote 5, no. 2

October 14, 1974

Interview, Rupert Garcia; story, Maria Alcorcha

-

“Celebration for new mural”

El Tecolote 14, no. 8

June 15–July 15, 1984

-

“Mission Street Manifesto” (illustration by Juana Alicia)

El Tecolote

December 1985

-

“A Mural is a Painting on a Wall Done by Human Hands”

El Tecolote 5, no. 1

September 13, 1974

Victoria Quintero

-

“New Mural to Commemorate Historic Strike”

El Tecolote

September 1985

Rebecca Rosen

-

“Creativity Explored: Focus on Self-Esteem”

El Tecolote

January 1986

Adele Ochoa

-

"Mission Muralists: Art Statements of the Mission"

El Tecolote 2, no 14

July 26, 1972

Carmen Castro interview of Michael Ríos

Community Murals

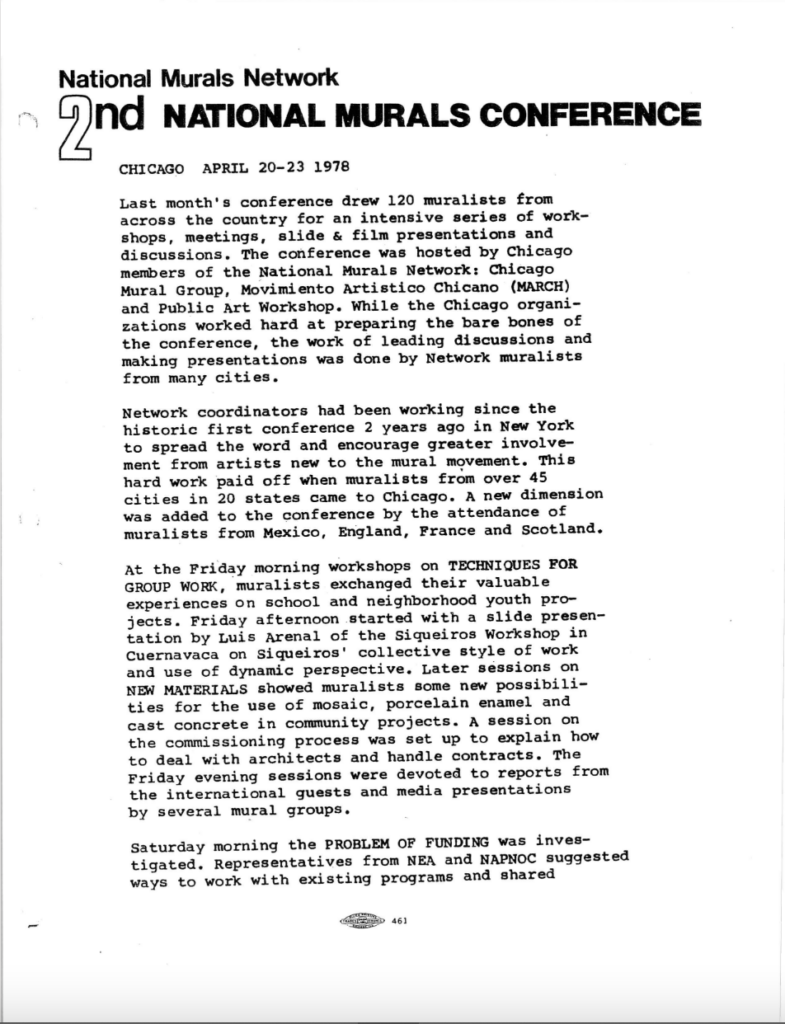

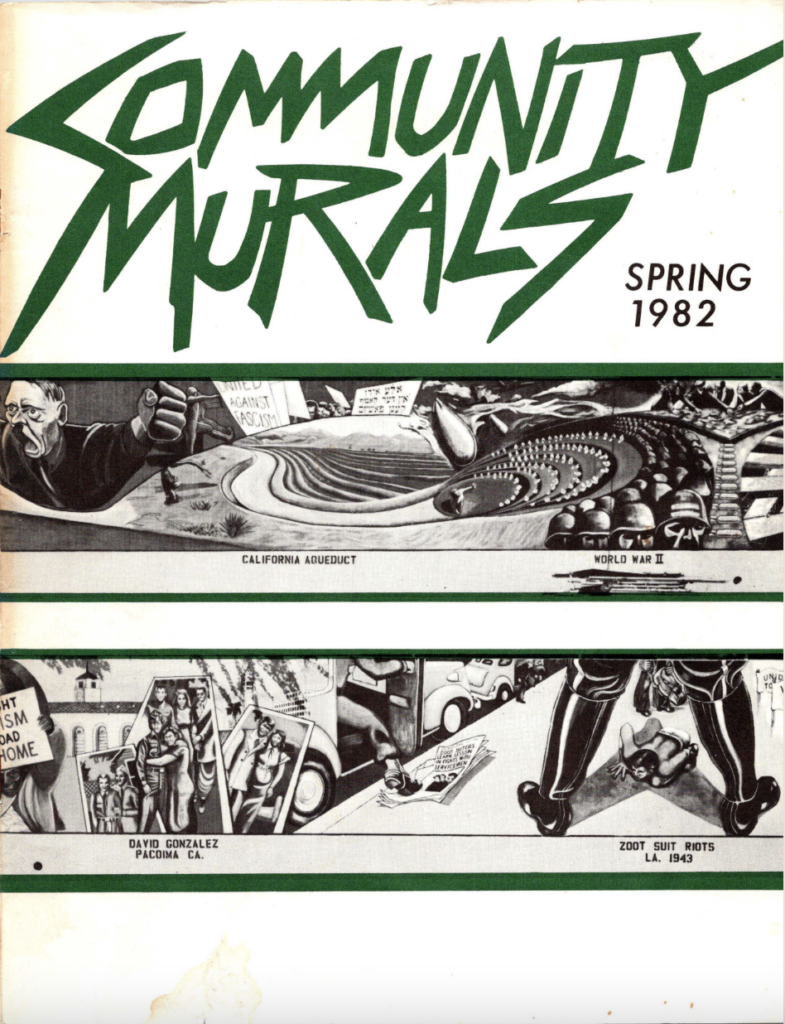

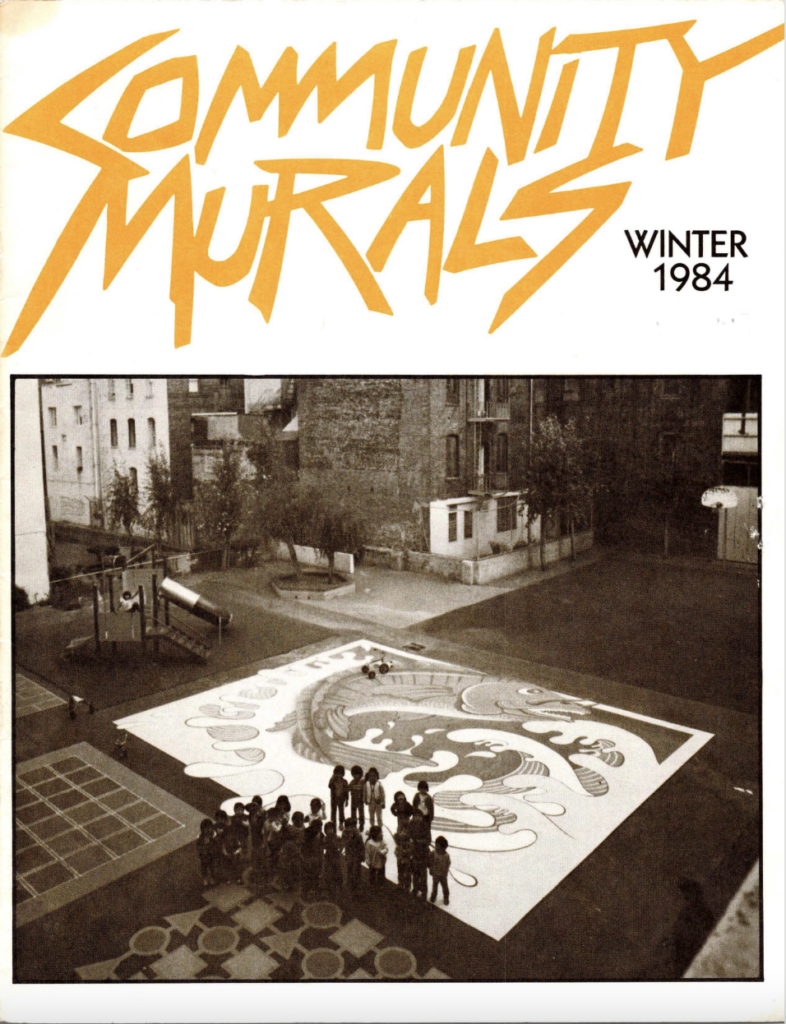

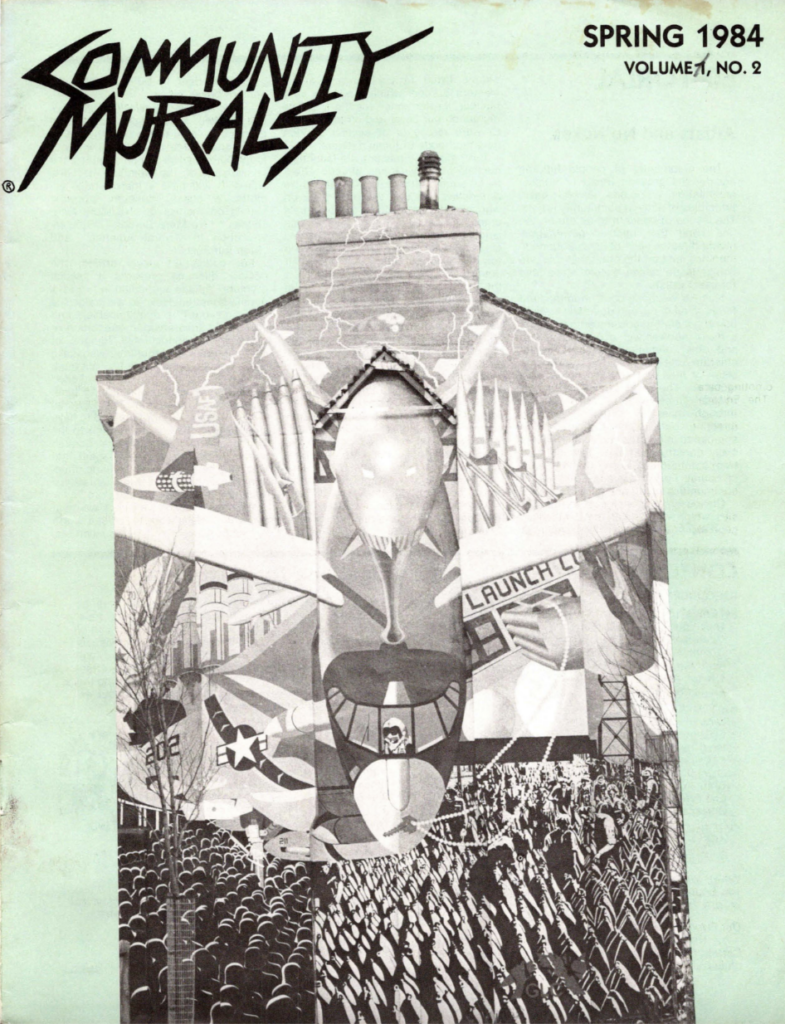

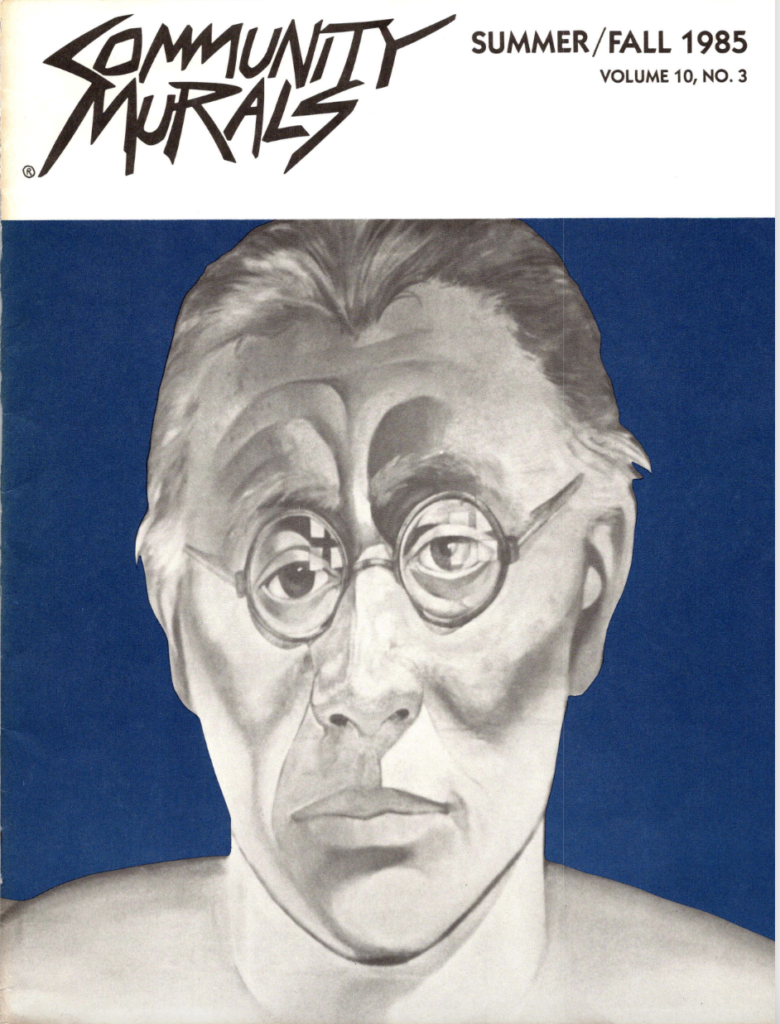

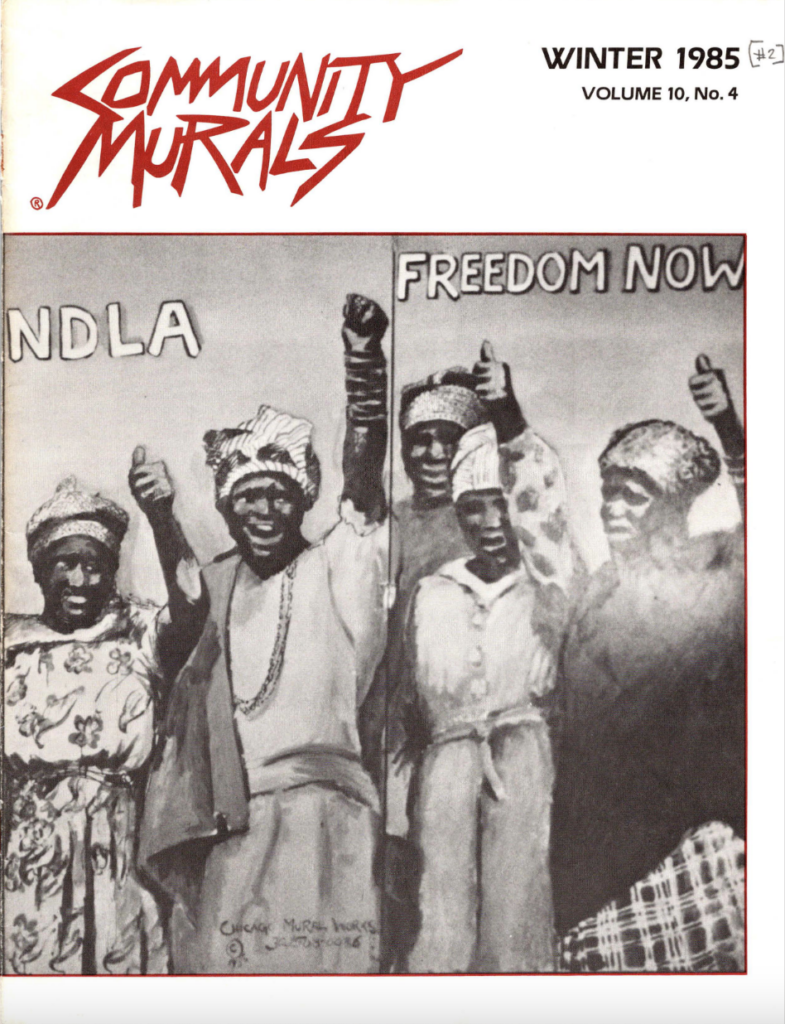

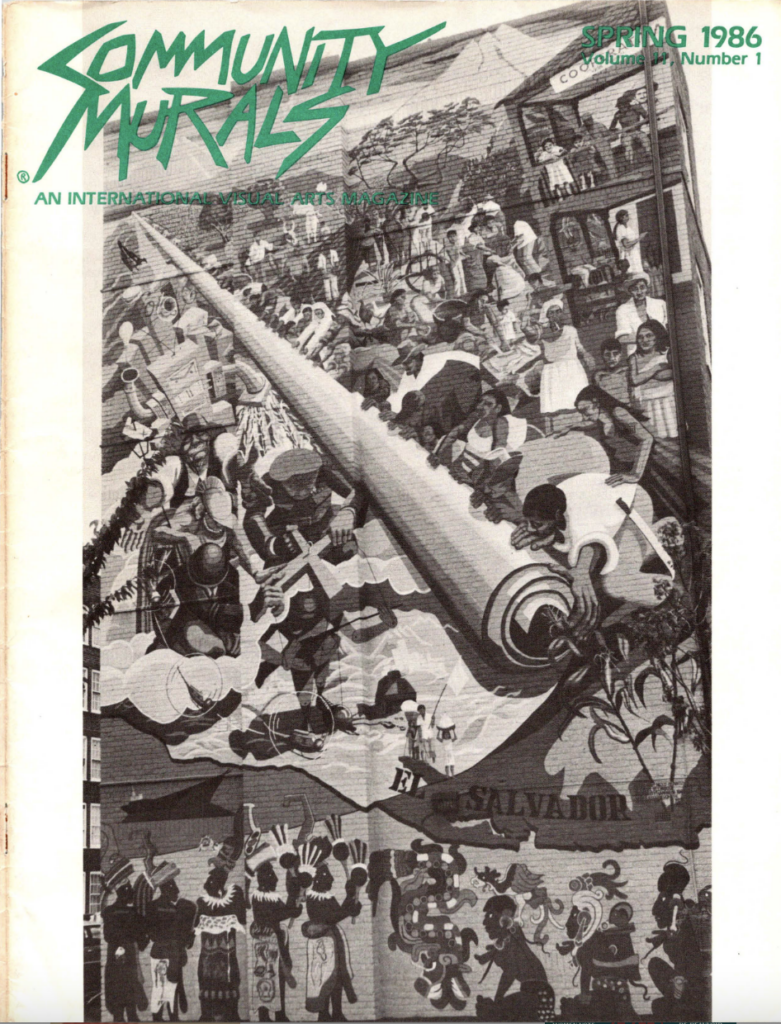

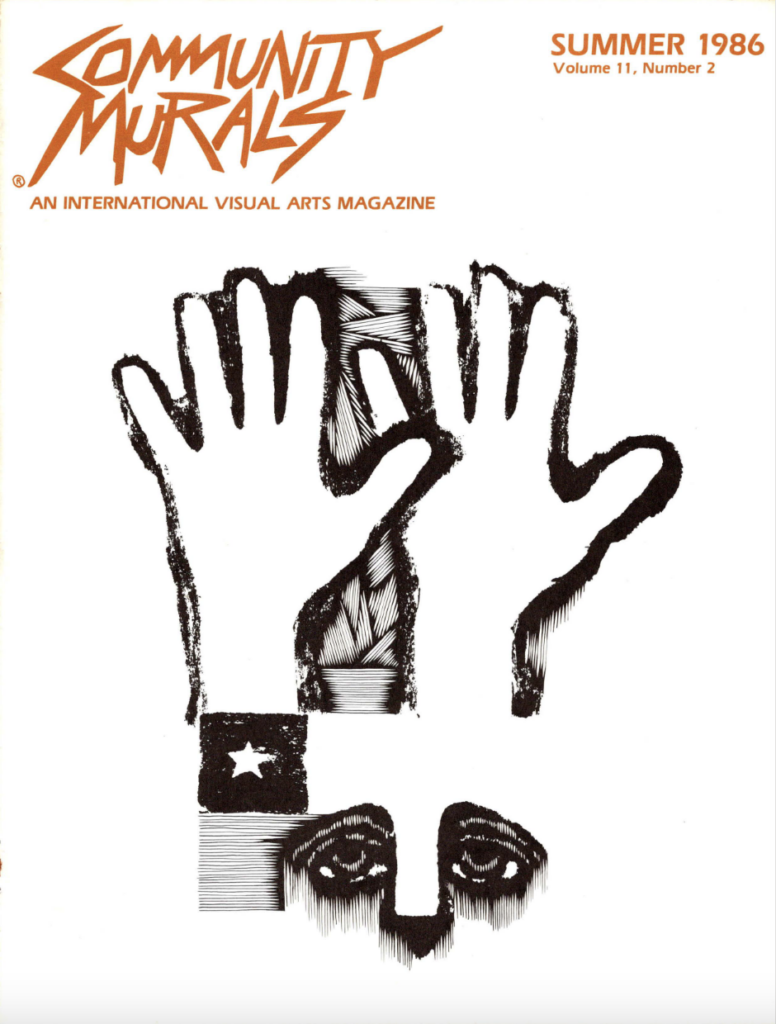

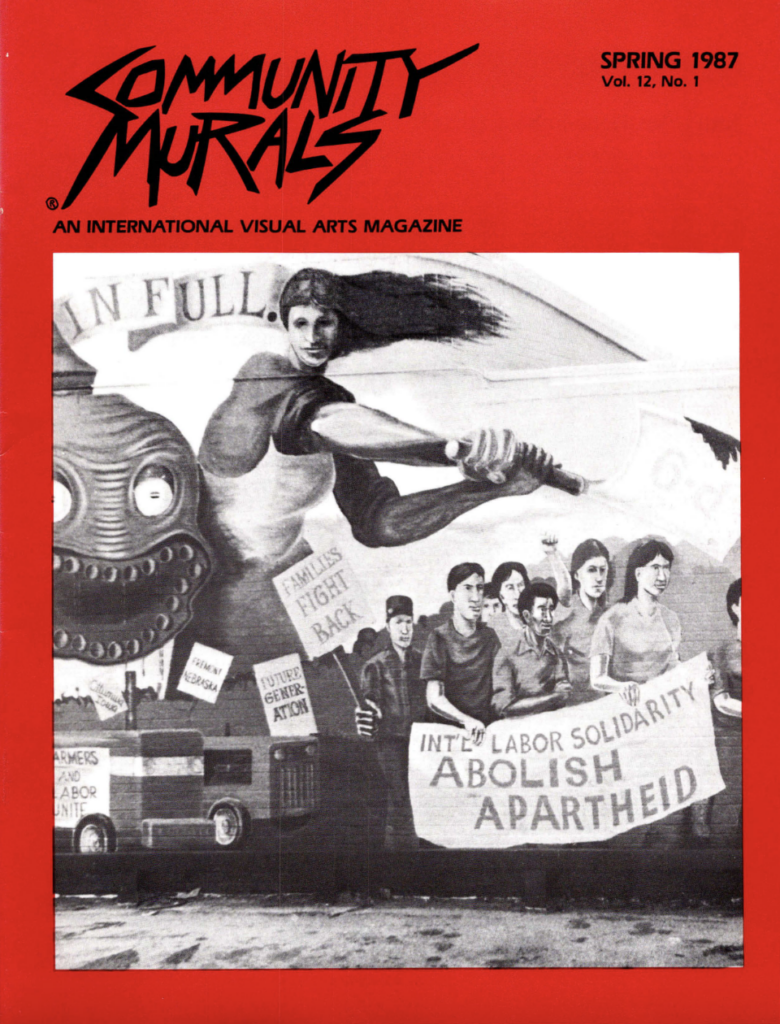

What started as a newsletter for the National Murals Network in 1977 evolved to become Community Murals magazine, a periodical that was published until 1987, with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and Galería de la Raza. The publication included documentation of and commentary on murals and related activism in the U.S. and internationally, profiles of muralists and artists committed to social activism, and listings of job and training opportunities for artists. Over the years the magazine’s editorial group included Kim Anno, Juana Alicia, Miranda Bergman, Kathy Cinnater, Dewey Crumpler, Lincoln Cushing, Jim Dong, Jo Drescher, Tim Drescher, Rupert Garcia, Nancy Hom, Claire Josephson, Lisa Kokin, Yolanda López, Dan Macchiarini, Emmanuel Montoya, Mike Mosher, Osha Neumann, Jane Norling, Ray Patlán, Odilia Rodriguez, Patricia Rodriguez, Jo Seger, David Shaw, Frances Valesco, Arch Williams, and Bill Young. The digital copies published here were created by archivist Lincoln Cushing and are also available at: https://www.docspopuli.org/articles/Community_Murals_Magazine_archives.html.

-

National Murals Network Newsletter, 1977

1977

-

National Murals Network Newsletter, 1978

1978

-

Report on National Murals Conference (Chicago, April 20–23, 1978)

April 20–23, 1978

-

Notes on 2nd National Community Muralists’ Network Conference, Chicago, Ill., April 20–23, 1978

April 20–23, 1978

-

National Murals Network International Newsletter, Winter 1979

Winter 1979

-

National Murals Network Community Newsletter, Fall 1979

Fall 1979

-

National Murals Network Community Newsletter, Spring 1980

Spring 1980

-

National Murals Network Community Newsletter, Fall 1980

Fall 1980

-

Community Muralists’ Magazine, Spring 1981

Spring 1981

-

Community Murals, Fall 1981

Fall 1981

-

Community Murals, Spring 1982

Spring 1982

-

Community Murals, Fall 1982

Fall 1982

-

Community Murals, Spring 1983

Spring 1983

-

Community Murals, Fall 1983

Fall 1983

-

Community Murals, Winter 1984

Winter 1984

-

Community Murals 9, no. 2 (Spring 1984)

Spring 1984

-

Community Murals 9, no. 3 (Summer 1984)

Summer 1984

-

Community Murals 9, no. 4 (Fall 1984)

Fall 1984

-

Community Murals 10, no. 1 (Winter 1985)

Winter 1985

-

Community Murals 10, no. 2 (Spring 1985)

Spring 1985

-

Community Murals 10, no. 3 (Summer/Fall 1985)

Summer/Fall 1985

-

Community Murals 10, no. 4 (Winter 1985)

Winter 1985

-

Community Murals 11, no. 1 (Spring 1986)

Spring 1986

-

Community Murals 11, no. 2 (Summer 1986)

Summer 1986

-

Community Murals 11, no. 3 (Fall 1986)

Fall 1986

-

Community Murals 11, no. 4 (Winter 1986)

Winter 1986

-

Community Murals 12, no. 1 (Spring 1987)

Spring 1987

-

Community Murals 12, no. 2 (Summer 1987)

Summer 1987

-

Community Murals 12, no. 3 (Fall 1987)

Fall 1987

-

Community Murals 12, no. 4 (Winter 1987)

Winter 1987

Murals and Muralists on Film

Mission Mediarts Archive

Since its start, Mission Mediarts has covered a wide range of local issues, including documenting murals and muralists working in the community, as can be seen from this selection. Initially, Mission Mediarts, Inc. (also known as MediaArts or Media Arts) evolved out of the Real Alternatives Program (RAP) and efforts to train Mission youth to work in film and television in the early 1970s. Responding to significant interest in media as a career and as a form of self-expression, Ray Rivera and Tony Miranda developed the idea for Mission Mediarts to train youth in video and film production and to document the neighborhood in contrast to the portrayals, or absence of portrayals, in the major media.[1] Jarmon “Ray” Balberan started working with the organization as one of the young producers in training, quickly becoming a collaborator and coleader of the organization. Many have contributed to the organization’s archive of work, including Ana Montano, Sara Ortiz, and Mercedes Soberon.

Mission Mediarts premiered their first episode of Mission and 24th Street on KQED, the local public television station, in the fall of 1971. The eighteen-part series launched with an episode dedicated to “Mission Musicians,” including a feature on Santana.[2] While KQED aired the series, Mission Mediarts publicly struggled with the station over insufficient funding and inadequate training for Mission youth working at the station.[3] After KQED declined to extend a contract with the organization, Mission Mediarts turned to airing programs about the Mission District on public access television.[4] In more recent years, Balberan has been uploading Mission Mediarts videos to his YouTube channel, including the following mural-related films.

Mujeres Muralistas (1974)

Archival video c. September 1974, 08:41 min. Features interviews with Consuelo Méndez and Patricia Rodriguez on the recent work of the Mujeres Muralistas and a reception for Paco’s Tacos, a restaurant that had commissioned a mural by the group.

Muralist Carlos Loarca painting the Mission Cultural Center (2017)

Video produced by El Tecolote and Mission Mediarts detailing the restoration of Loarca’s mural on the front facade of the Mission Cultural Center, titled Spirit of the Arts (1982), in 2017. (05:07)

RAP High School Murals and Our Love for Mario (2020)

A short film created by the Conscious Youth Media Crew with Carlos “Kookie” Gonzalez, displaying murals created by the Real Alternatives Program in 2020. (07:32)

San Francisco State also houses The Ray Balberan Mission MediaArts Archive online as part of its Bay Area TV Archive. Multiple films present unique glimpses of mural life in the Mission.

Wall Murals Being Painted in the Mission District I (1970s)

This 16mm film includes close-ups of murals in the 24th Street Mini Park, including Quetzalcoatl, as well as images of Graciela Carrillo, Patricia Rodriguez, Michael Ríos, and others painting. (04:09)

Wall Murals Being Painted in the Mission District II (1970s)

The film features muralists Michael Ríos, Anthony “Tony” Machado, and Domingo Rivera working in the 24th Street Mini Park and eating together at a local cafe with friends, including Benny Rescate, Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez, Ray Rivera, and Ana Montano. (04:18)

Wall Murals Being Painted in the Mission District III (1970s)

Filming of Patricia Rodriguez and Graciela Carrillo on a scaffold painting Fantasy World for Children and close-ups of several artists and murals in the 24th Street Mini Park. (03:29)

24th and Mission (1976)

Includes footage of a Galería de la Raza billboard by Xavier Viramontes, the untitled 24th Street BART mural by Michael Ríos, Anthony “Tony” Machado, and Richard Montez, the Vietnamese mural by Michael Ríos, and Domingo Rivera’s Psycho-Cybernetics mural in the 24th Street Mini Park. (10:09)

The CIA Mural (1976)

Filming of Domingo Rivera’s CIA mural at Garfield Park. (2:33)

Excerpts from an Interview with Luis Cortazar (1976)

Excerpts from an interview by Sara Ortiz of muralist Luis Cortazar, no sound. (1:49)

Close-up shots of wall murals in Mission District I (1977)

Filming of an untitled mural on the exterior of the Bernal Dwellings completed by Michael Ríos, Graciela Carrillo, Sekio Fuapopo, Patricia Rodriguez, and Frances Valesco. The film also includes close-ups of Domingo Rivera’s CIA mural and Gilberto Ramírez’s LULAC mural. (4:07)

The Freedom Archives

The Freedom Archives houses extensive audiovisual documentation related to progressive movements throughout the world, the United States, and the Bay Area from the late sixties through the mid nineties.

Frente Conference (1975)

Video from the Frente Conference for cultural workers held in San Francisco in 1975 opens with Consuelo Méndez, one of the Mujeres Muralistas, talking about what murals mean to her. The video is part of the Freedom Archives collection. (23:39)

Califas: Chicano Art and Culture in California Conference (1982)

The Califas conference held at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1982 brought together some of the state’s leading Chicanx/Latinx artists to discuss the history, aesthetics, and future of Chicano art and culture. Participants included Judy Baca, Carmen Lomas Garza, Amalia Mesa-Bains, José Montoya, Malaquias Montoya, Patricia Rodriguez, Luis Valdez, Patssi Valdez, and many more. The conference evolved from a group art exhibition held in 1981 at the Mary Porter Sesnon Gallery at University of California Santa Cruz. In the conference grant proposal, art professor Eduardo Carrillo envisioned the exhibition and the conference as opportunities “to bring together, to document, and to stimulate the work of artists who have had a significant impact on the Mexicano/Chicano arts movement in California.”[5] Even more grand, Carrillo, with significant support from Juventino Esparza, Philip Brookman, and Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, intended to create a comprehensive resource on Chicano art. Thus, the conference not only stirred lively debate but continues to stand out for creating an unprecedented film archive of California’s Chicano art community at that time. Filmmakers Philip Brookman (also then at UC Santa Cruz) and Amy Brookman conducted extensive interviews with many of the attending artists, some of which were incorporated into their documentary Mi Otro Yo (My Other Self) (1986). While the Califas collection is now housed at the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archive at the University of California Santa Barbara, part of the Online Archive of California, the videos are available in the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/ucsantabarbara.

The Califas conference included a variety of discussions on murals and mural making throughout California. The project expanded to incorporate filming murals on location in San Francisco’s Mission District. Here are selected videos from the Califas project that offer meaningful documentation for Proyecto Mission Murals.

Murals, Mission District, San Francisco (part 1 of 2) (1983)

Footage of the Mission District, focusing on the mural Carnaval (1983). Audio conversations with passersby giving their impression of the imagery is provided over detailed shots of the murals. (14:21)

Murals, Mission District, San Francisco (part 2 of 2) (1983)

Footage of the Mission District in August 1983, showing street scenes and pedestrians over ambient sounds of the neighborhood, and featuring the Women’s Contributions mural on the Women’s Building and Graciela Carrillo’s Humanidad mural on the Mission Neighborhood Health Center. (20:21)

Interview with René Yañez (1982)

Presented in three separate videos, most of this footage documents various neighborhood murals, sometimes with passersby giving their thoughts about the murals. Total duration of the footage is 01:06:29. The interview of René Yañez begins in the last half of the third film. Murals appear as follows:

In part 1: Latino America and Native American Mexicans

In part 2: 24th Street BART mural and Para el Mercado (Paco’s Tacos)

In part 3: Quetzalcoatl, Fantasy World for Children, and ABC (all in the 24th Street Mini Park); and the Día de los Muertos Billboard at Galería de la Raza

Interview with René Yañez and Ralph Maradiaga (1982)

Yañez discusses his creative projects and the origins of Galería de la Raza. Maradiaga reflects on his creative growth since cofounding Galería de la Raza and displays some of his graphic work. (01:21:48)

Interviews with Carmen Lomas Garza and Patricia Rodriguez (1982)

Garza shows her work while describing her creative background and subject matter—positive scenes of day-to-day life in the Chicano community. Rodriguez discusses her time in the Mujeres Muralistas and emphasizes how working as a group forged a diverse representation of the cultures that Mission District community comprises. (02:04:12)

Interview with Amalia Mesa-Bains (1982)

Mesa-Bains reflects on her childhood in San Francisco, her move into the Chicano art movement, her teaching work in psychology, and her ongoing involvement in art. (01:21:28)

Interview with Ray Patlán (1982)

Patlán discusses his early mural projects on Chicago’s South Side, the wave of creative projects in Chicano communities throughout the U.S. during the 1970s and 1980s, and his personal and public work since his move to the Bay Area in 1975. (01:04:56)

Daniel del Solar Archive

The cosmopolitan media activist Daniel del Solar grew up among artists and lived in Mexico and various parts of the United States. During his time working in Bay Area television, he produced a handful of short films related to mural making and the community mural movement. Del Solar’s papers are archived at the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archive at the University of California Santa Barbara, which has also made some of his filmwork available online.

Diego Rivera’s Fresco Murals, Community Murals, and Nueva Cancion en las Americas

A collection of three short undated films. In the first, del Solar interviews Lucienne Bloch and Stephen Pope Dimitroff, who both apprenticed under Diego Rivera and went on to train several generations of artists on the techniques of creating murals and inform the work of many artists featured in this project. Bloch and Dimitroff reflect on their early years with Rivera and the political climate of the 1930s that influenced their work during that time. The next video, created for KQED in 1976, provides an overview of contemporary community murals throughout the United States, including the Wall of Respect (1967) on Chicago’s South Side. The final film is a performance of the song “Nueva Cancion en las Americas” from the same time period. (55:18)

Fresco Workshop—Lucienne Bloch and Stephen Pope Dimitroff (c. late 1980s / early 1990s)

Daniel del Solar encouraged Bloch and Dimitroff to document their class on creating frescoes. He filmed the entire ten-part workshop, which included various interactions with students, discussions with del Solar, as well as lectures on techniques and fresco history. Bloch and Dimitroff taught fresco making in the Bay Area for decades. This filmed series was made available on the Internet Archive in 2013. (08:19:37)

Notes

- “How Mission Mediarts Is Altering a Stereotyped Image,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle, October 10, 1971.

- “Tonight’s Best Bets on TV,” San Francisco Examiner, October 4, 1971.

- Dexter Waugh, “Mission Group Battles KQED,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle, March 4, 1973; “KQED, Latinos in a Deadlock,” San Francisco Examiner, April 3, 1973.

- Janet Gendler, “How to Produce Your Own TV Shows on Access Cable,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle, March 26, 1978.

- Eduardo Carrillo, “‘Califas’: Chicano Art and Culture in California,” excerpts from planning grant submitted to the National Endowment for the Humanities, 1981, digitally archived in Documents of Latin America and Latino Art, International Center for the Arts of the Americas, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, https://icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/847475.

Contributors

Essays

Cary Cordova

Associate professor of American Studies, University of Texas at Austin

Ella Maria Diaz

Professor and chair, department of Chicana and Chicano Studies, San José State University

Terezita Romo

Art historian, curator, writer, and associate faculty and lecturer in Chicana/o Studies at University of California, Davis

Mauricio Ramírez

Artist, curator, and University of California President’s and Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in Chicana/o Studies at University of California, Davis

Biographies

Kevin Cruz Amaya

PhD candidate in Chicano/o/x Studies and Central American Studies at University of California, Los Angeles

Camilo Garzón

Writer, editor, voice director, poet, interdisciplinary artist, oral historian, multimedia producer, journalist, and educator.

Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez

PhD candidate in Chicano/o/x Studies and Central American Studies at University of California, Los Angeles

Community Advisory Committee

Juana Alicia

Muralist, printmaker, illustrator, and educator; founding director of the True Colors Mural Project

Susan Kelk Cervantes

Mural artist and founding director of Precita Eyes

Lydia Chavez

Founder and editor of Mission Local and former journalism professor at University of California Berkeley

Tim Drescher

Former co-editor of Community Murals magazine and author of San Francisco Bay Area Murals: Communities Create Their Muses, 1904–1997

John Jota Leaños

New media artist and assistant professor of social documentation at University of California Santa Cruz

Fátima Ramírez

Cultural arts curator and interim executive director of Acción Latina

Josué Rojas

Mural artist, educator, and former executive director of Acción Latina

Melissa San Miguel

Curator, arts educator, and MA/PhD student of art history and archaeology at the University of Maryland, College Park

Project Team

Harmony Baker

Intern, Interpretive Media

Noah Biavaschi

Web Developer, SFMOMA

Javier Briones

Filmmaker, 32K Productions

Kevin Carr

Producer, Interpretive Media, SFMOMA

Sylvia Castillo

Website Product Manager, SFMOMA

Julie Charles

Deborah and Kenneth Novack Director of Education, SFMOMA

Chad Coerver

Former Leanne and George Roberts Chief Education and Community Engagement Officer, SFMOMA

Cary Cordova

Associate Professor of American Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Kari Dahlgren

Director of Publications, SFMOMA

Natalia De La Rosa

Intern/Production Assistant, Interpretive Media, SFMOMA

Laila E. Dreidame

Former Associate Director, Foundation and Government Partnerships, SFMOMA

Claudia Escobar

Film editor

Erin Fleming

Former Content Producer, Interpretive Media, SFMOMA

Erica Gangsei

Director of Interpretive Media, SFMOMA

Stephanie Garcés

Former Education and Community Engagement Coordinator, SFMOMA

Camilo Garzón

Oral historian and audio zine director

Santino Gonzales

Associate Content Producer, Interpretive Media, SFMOMA

Tomoko Kanamitsu

Barbara and Stephan Vermut Director of Public Engagement, SFMOMA

Myisa Plancq-Graham

Content Producer, Interpretive Media, SFMOMA

Tamara Porras

Former Manager of Educator Engagement, SFMOMA

Jessica Ruiz DeCamp

Former Assistant Editor, Publications, SFMOMA

Melissa San Miguel

Project researcher

Fengxue Zhang

Interpretive Media Coordinator

Many current and former SFMOMA staff provided essential support for the project, including Paul Armstrong, Deane Brannen-Jurgenson, Maria Castro, Gillian Edevane, Ian Gill, Clara Hatcher Baruth, Rebecca Herman, Bosco Hérnandez, Megan Kiskaddon, Julie Lamb, Samantha Leo, Mei Li, Jenn Livermore, Stella Lochman, Marla Misunas, Lucy Medrich, Christo Oropeza, Cecilia Platz, Caroline Stevens, Anna Tang, Adine Varah, and Misty Youmans.

The project team extends additional thanks to the following: Josiah Luis Alderete and Olivia Peña, narrators of the audio zine; Victor Altamiro, Beth Chapple, Ida Galván, Lucy Laird, Inés Marcos, and Rachel Walther, who provided editorial support; Gina Broze, rights and image research coordinator; transcribers Celeste Lindahl and Mary Geitz; and translators Jane Brodie, Odette León, Mario Mireles, and Melisa Palferro. For their work on the documentary, we thank Chris Tipton-King, videographer, along with Venezuela crew members Edwin Corona Ramos, cinematography; 2nd camera, Stefania Chehade; and Gustavo Vera, sound recordist.

Copyright © 2022 by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 151 Third Street, San Francisco, California, 94103. All rights reserved. This digital publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Texts by Cary Cordova are © Cary Cordova.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, MA-10-19-0250-19

The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this digital publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.