Richard Artschwager’s Portrait of Holly (1967–68) (fig. 1) blends drawing, painting, and photography to present the vivacious New York art dealer Holly Solomon in a rare moment of repose. On a fibrous Celotex insulation panel set in a silvery metal frame that echoes the composition’s grisaille background, Solomon sits in an ornate chair and looks directly at the viewer. The intricate lines of acrylic paint and faint layers of charcoal and graphite meticulously enlarge a picture by the photographer William John Kennedy, who documented the New York Pop world in the 1960s—including many artists who exhibited alongside Artschwager at the influential Leo Castelli Gallery.1 Solomon herself joined the Pop circle around this time and appeared in pictures by Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein that fuse her likeness with imagery from popular culture. In Portrait of Holly, however, her crisp form emerges out of the unique combination of photorealistic techniques and building materials that distinguishes Artschwager’s art from the grain of Pop, exemplifying the ways in which his oeuvre deceives perception and questions the boundaries between reproduction, decoration, and fine art.

Born in 1923, Artschwager began his career as an artist in 1959 after serving as a United States Army intelligence officer in World War II, taking odd jobs as a baby photographer, and becoming a successful furniture maker and designer. This eclectic background informed his production of visually confounding sculptures such as Table and Chair (1962–63) (fig. 2), in which a table and chair are painted with an enlarged black-and-white wood grain facsimile, and Formica-covered works such as Triptych III (1967). In each, an illusionistic surface distorts the form and function of the underlying object. As the artist said of one of his Formica pieces in 1965, “It’s not sculptural. It’s more like a painting pushed into three dimensions. It’s a picture of wood. . . . It’s a multi-picture.”2 His three-dimensional constructions often recall familiar domestic furnishings and, like Minimalist artworks, inhabit our shared space. Yet, covered with exaggerated patterns, they also appear curiously melded with two-dimensional representation.

2. Richard Artschwager, Table and Chair, 1962–1963; Wood table, wood chair, and acrylic paint, 29 1/2 x 23 x 16 1/2 in. (74.93 x 58.42 x 41.91 cm); collection SFMOMA; Gift of Helen and Charles Schwab through The Art Supporting Foundation; © Estate of Richard Artschwager / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: Katherine Du Tiel

Critics variously grouped Artschwager’s work with Pop for its use of everyday materials and appropriated imagery; Minimalism for its austere, solid constructions on a human scale; and Conceptual art for its cerebral underpinnings. But Artschwager consistently eschewed fixed labels.3 Around 1961 he began to make paintings based on found photographs and newspaper images, inspired by a snapshot he discovered in a trash pile on the street that showed ordinary beachgoers whom he decided to portray “as they were without satire.”4 He delicately replicated such anonymous images on the tactile surfaces of Celotex insulation panels, often crafting striking artist’s frames to give the works a sculptural presence—an inverse of the flattening patterns he applied to his three-dimensional constructions. In characteristically deadpan fashion, he later wrote: “I am engaged in the making of painting and sculpture (pictures and objects). These are flat things and things which are not flat.”5 Drawing his materials and subject matter from our common surroundings, he continually upended the seemingly stable categories of physical objects and pictorial illusions.

In Portrait of Holly Artschwager has not just duplicated but also magnified his source image with exacting precision through a combination of techniques culled from drawing and painting. Kennedy’s original high-contrast portrait (fig. 3) shows Solomon seated against a stark white background that draws the eye to the fine points of the ornate chair and the decorative flourishes on her suit, blouse, and shoes. Artschwager managed to render these sharp details despite the coarse surface of his Celotex support. As he later explained, “Celotex . . . had this roughness, the look of pinhole photographs. You see, it replaced the human touch that the photo didn’t have. . . . I wanted something that had the feel of drawing, the character of painting, and introduced the look of mechanical reproduction.”6 Delicate layers of charcoal and graphite and thin lines of acrylic paint seem at times to trace the texture of the panel, particularly in the granular background. In other areas Solomon’s image is set in clear relief, as in the defined outlines of her jacket and hands. Carefully blended shadows and highlights shape the collar of her blazer and the point of her shoe, both of which appear to project off the surface of the composition in a trompe l’oeil effect. A smooth varnish wash affixes the various media to the support and lends a photorealistic gloss to the work.

4. Richard Artschwager, Holly’s Knee, n.d.; acrylic paint on Celotex in metal artist’s frame, 29 in. x 11 1/2 in. (73.7 cm x 29.2 cm); Norton Museum of Art; Purchase, R. H. Norton Trust, 2012.29; Digital Image © Norton Museum of Art

A group of related Celotex works reveal Artschwager’s almost mechanical approach of isolating and enlarging abstracted segments of Kennedy’s picture to reproduce the photographic details in paint. In 1983 he described his practice of “gridding . . . an ‘anonymous’ photograph and reproducing it square by square, giving oneself to the making of each square independently of the whole, indifferent to the whole. . . . I elaborated a technique that embodied drawing, painting and some chemical action vaguely akin to photography.”7 The dramatic crop of Holly’s Knee (fig. 4) reduces the titular subject to a barely recognizable white oval, focusing instead on the patterns in the carved wood and the depth of space in the background. Two other small works attend to the direct light and the reflections that brighten the hand holding the wine glass, the stockinged knee, and the gleaming point of the shoe over the chair’s frame. Carefully selected for study from Kennedy’s photograph, these luminous elements resurface as visual anchors in the complete portrait.

The artist also experimented with the effects of frames in these related paintings, testing thick and thin metal borders and a simple wood encasing to counter the flat pictorial illusion with the weight of materials from common domestic settings. In the 1960s Artschwager had begun using commercially produced grooved aluminum frames that not only echoed the gray tones of his artworks but also reflected their surroundings.8 Like the pulpy surface of the support, the substantial metal frame seems to transport this portrait into the realm of three-dimensional decoration, projecting off the picture plane with three inset layers that often run parallel to the carefully rendered woodwork in the chair. It both relates to the image and asserts the object’s physical presence, fusing art with our environment.

Alongside Artschwager’s interest in folding the ordinary into fine art, the photographer of the source image for Portrait of Holly and the subject herself point to the artist’s loose connections to the New York Pop world. Kennedy began his career in the 1950s as an assistant studio manager for the Vogue fashion photographer Clifford Coffin before leaving to work as a freelance commercial and editorial photographer. In the early 1960s he became close with Pop artists such as Warhol and Robert Indiana and documented the rise of Pop in his images of key figures such as Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Claes Oldenburg. Solomon, who was born Hollis Dworkin, also forged ties with many of these artists. Before becoming a collector in the 1960s she studied theater and art history at Vassar College, in Poughkeepsie, New York, and Sarah Lawrence College, in Bronxville, New York, and even pursued acting under the stage name Hollis Belmont.9 Known as the “princess of Pop,” Solomon leveraged her vibrant, theatrical personality to gain stature among artists, critics, and gallerists and to build her collection.10 She went on to become a pioneering New York art dealer when she and her husband, Horace Solomon, opened the alternative arts space 98 Greene Street loft in 1969 and Holly Solomon Gallery in 1975.

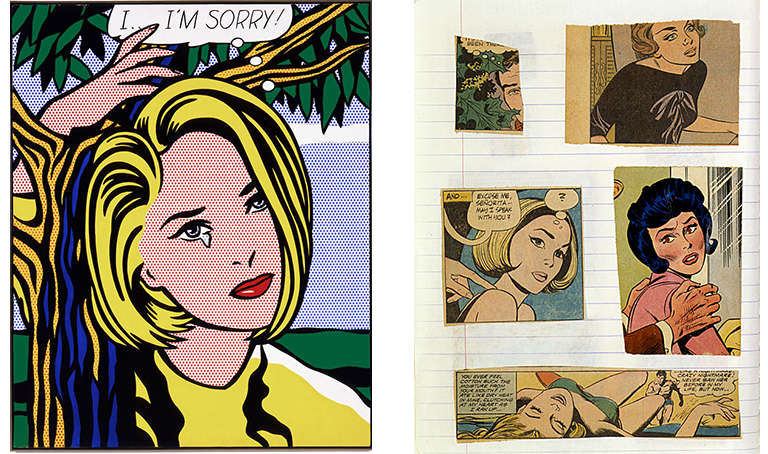

5. Roy Lichtenstein, I . . . I’m Sorry!, 1965–66; oil and Magna on canvas, 60 in. x 48 in. (152.4 cm x 121.9 cm); The Broad, Los Angeles

6. Clippings from comic strips pasted into one of Roy Lichtenstein’s composition notebooks, n.d.

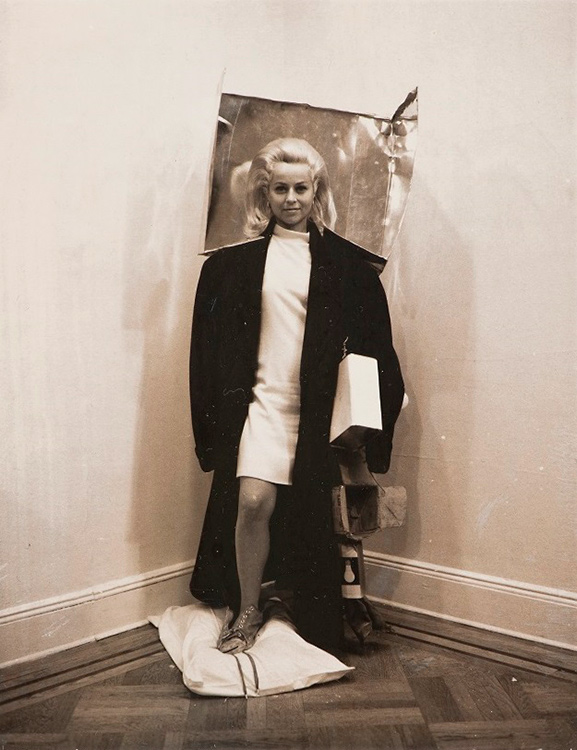

7. Robert Rauschenberg, photograph of Holly Solomon, 1966

By the time she commissioned Portrait of Holly, Solomon had already been depicted by several figures associated with the rise of Pop art. She and her husband had commissioned Lichtenstein’s I . . . I’m Sorry! (1965–66) (fig. 5), a picture of a blond woman giving a dramatic, tearful apology that fuses Solomon’s likeness with the comic book imagery the artist saved in notebooks and repainted with his iconic, enlarged benday dots (see fig. 6).11 In 1966, Rauschenberg staged a photograph of Solomon (fig. 7) that seems to integrate her into one of his famous Combines, hybrid constructions that incorporate ordinary found objects and that borrow from both painting and sculpture. Shown in a white cocktail dress, Solomon humorously plays the role of the tramp, holding a stack of old boxes and sporting an oversize coat and a single worn sneaker. Warhol’s Holly Solomon (1966) (fig. 8) comprises one frame of a photobooth strip (fig. 9) enlarged to produce nine luridly colored, high-contrast screenprinted canvases in which Solomon’s boldly outlined lips recall those of the sultry French film star Brigitte Bardot.12 Each of these works blends imagery and materials from everyday life and media to present Solomon playing a type or character, furthering the Pop interest in merging mass culture and fine art.13

8. Andy Warhol, Holly Solomon, 1966; acrylic, silkscreen ink, and graphite on linen; nine panels, each: 27 in. x 27 in. (68.6 cm x 68.6 cm); overall: 81 in. x 81 in. (205.7 cm x 205.7 cm); Collection of Jonathan Colby, Miami

9. Andy Warhol, Holly Solomon, ca. 1965; gelatin silver print, 7 13/16 in. x 1 9/16 in. (19.8 cm x 4 cm); The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of Holly Solomon

Artschwager’s portrait of Solomon similarly combines commercial materials and photographic imagery, but it presents her in a domestic setting with close, intimate framing. Instead of filtering her image through the lens of popular culture, it takes cues from more familiar surroundings. Solomon appears as she might in an ordinary snapshot, donning a stylish designer suit and holding a glass of wine in her hand, comfortably perched on her folded leg. The life-size scale, tactile support, and metal frame seem to extend the personal realm of the scene into the space of the viewer. In its monumental depiction of a seemingly quotidian photograph, Portrait of Holly exemplifies Artschwager’s efforts to push the boundaries of Pop, Minimal, and Conceptual art and blur the lines between object and representation, surface and material, decoration and fine art.

Notes

- Artschwager’s early exhibitions after signing with Leo Castelli Gallery include Introducing Artschwager, Christo, Hay, Watts (May 2–June 3, 1964); Group Exhibition: Artschwager, Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, Stella, Warhol (September 26–October 22, 1964); and Artschwager (January 30–February 24, 1965).

- Richard Artschwager in Jan McDevitt, “The Object: Still Life,” Craft Horizons 25, no. 5 (September/October 1965): 54.

- One critic wrote of a 1968 exhibition of Artschwager’s work, “The Pop feeling hung on—the few grisaille paintings included seemed as though they might even be intended as part of an environmental decor of dreadfulness. But at the same time, their very wide frames turned them almost into objects.” Elizabeth C. Baker, “Artschwager’s Mental Furniture,” Art News 66, no. 9 (January 1968): 60.

- Richard Artschwager in “Answers to Coosje van Bruggen” (1983), in Richard Artschwager: Texts and Interviews, ed. Dieter Schwarz (Düsseldorf: Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 2003), 92.

- Richard Artschwager, “Excerpts from the Notebooks of Richard Artschwager” (1965), in Richard Artschwager: Up and Across (Nuremberg, Germany: Neues Museum in Nürnberg, 2001), 68.

- Richard Artschwager in Steven Henry Madoff, “Richard Artschwager’s Sleight of Mind,” Art News 87, no. 1 (January 1988): 118.

- Richard Artschwager in “Answers to Coosje van Bruggen,” 92.

- Richard Armstrong, Artschwager, Richard (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1988), 29; and Jennifer R. Gross, “Absolutely Original,” in Richard Artschwager! (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2012), 9.

- Erik La Prade, Hooray for Hollywood: Celebrating Holly Solomon (New York: Mixed Greens Gallery and Pavel Zoubok Gallery, 2014), 5.

- Barbaralee Diamonstein, for example, noted that the critic Robert Rosenblum referred to Solomon as “a princess of Pop of the 1960s.” Barbaralee Diamonstein, “Holly Solomon,” in Inside the Art World: Conversations with Barbaralee Diamonstein (New York: Rizzoli, 1994), 240. Similarly, Solomon recalled, “During the heyday of Pop, I was camping. I understood its value—I wasn’t an important collector with the stature. . . . I was, however, young, spontaneous and pretty. I played a role—the Pop Princess. . . . The role threatened no one, and I went everywhere.” Holly Solomon in Neil Printz, “An Interview with Holly and Horace Solomon, June 1982,” in Holly Solomon Gallery: Inaugural Exhibition, ed. Richard Armstrong (New York: Holly Solomon Gallery, 1983), 19.

- See Roy Lichtenstein’s online catalogue raisonné: Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, “Image Duplicator,” www.imageduplicator.com. Lichtenstein made few portraits over the course of his career; as the catalogue raisonné entry for Bobby Kennedy (1989) notes: “Bobby Kennedy is one of the very few portraits Lichtenstein has ever done in any medium. Holly Solomon appears as the tearful blonde in the painting I . . . I’m Sorry.”

- Georg Frei and Neil Printz, ed., The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculptures, 1964–1969, vol. 2B (London: Phaidon, 2002), 262–63.

- See Thomas Crow, The Long March of Pop: Art, Music, and Design, 1930–1995 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015). Solomon described seeing her commissioned portrait by Lichtenstein: “I was overwhelmed—I felt like an archetype of my time.” Solomon in Printz, “An Interview with Holly and Horace Solomon,” 18.