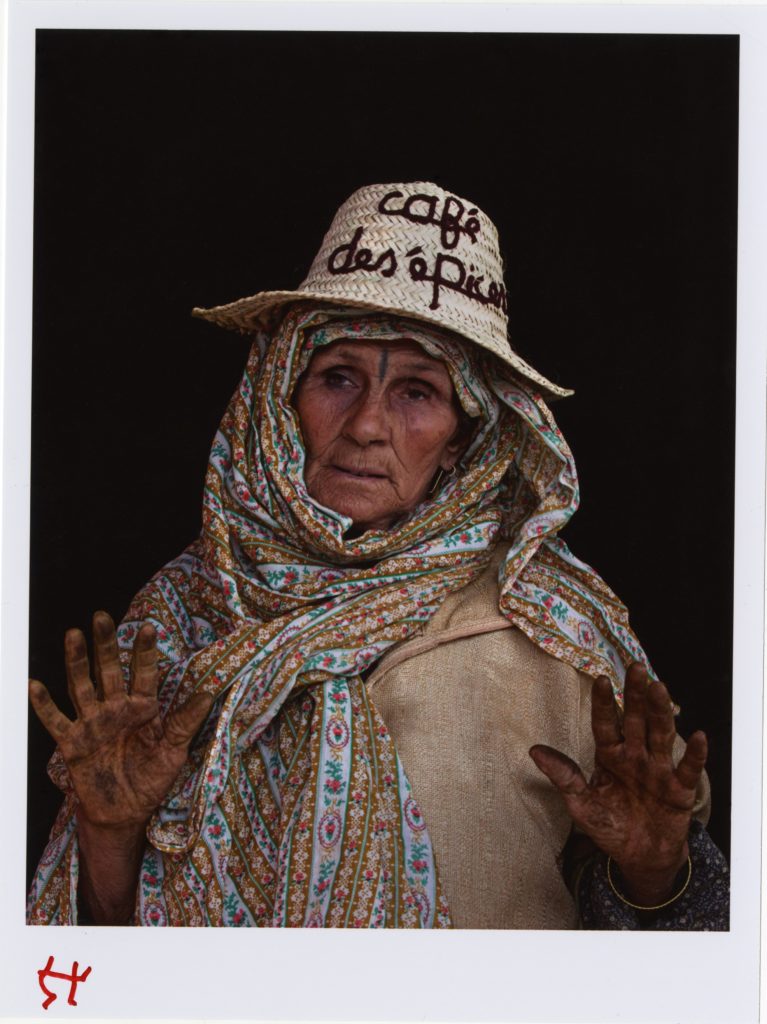

Signed portrait, Marrakech, Morocco, from the project 20 dirhams or 1 photo?, 2013

A set of persistent questions has guided Susan Meiselas’s work since the very beginning of her career: Whom are these pictures for? Whom do they serve? What are the responsibilities of the photographer toward her subject? Meiselas’s deeply ethical practice hinges on a transformation of the charged relationship between the person photographing and the person being photographed from one of power, to one of exchange. As she elaborated in an interview in 2008: “I’ve always felt uncomfortable about taking something away without reciprocating. In allowing one’s picture to be taken, someone is consenting to be a subject. And what am I giving in return? It’s a form of exchange as well as a feeling of photography being a wonderful gift.”1 Though the crucial importance of this relationship between photographer and subject has always been evident in Meiselas’s work, it became the explicit subject of a commission she completed in Morocco in 2013 entitled 20 dirhams or 1 photo?

Meiselas and four colleagues from the Magnum Photos agency (Abbas, Jim Goldberg, Mark Power, and Mikhael Subotzky) were invited to Marrakech in 2013 to create a portrait of the city that would form the inaugural exhibition for the Marrakech Museum of Photography. It was an unusual and challenging commission, partly by design. The parameters were broad and the timeline extremely short: the artists had a mere two weeks from their arrival in the city to conceive a project and complete the final exhibition. Moreover, the photographers were encouraged to work together and to engage the local community of artists. For most of the Magnum photographers, Marrakech was unfamiliar territory. Each had to move quickly to find his or her bearings and craft an artistic response.

Installation of 20 dirhams or 1 photo?, Marrakech Museum for Photography and Visual Arts, 2013

Meiselas knew from the outset that she wanted to work with women and women’s organizations but did not immediately find an approach that felt right. The first week produced a series of iterative ideas, but no clear direction, and she felt keenly that her time was growing alarmingly short. Not only was the physical setting completely new and the culture unfamiliar, but Meiselas and her cohort encountered another obstacle: by and large, the people of Marrakech did not want to be photographed.

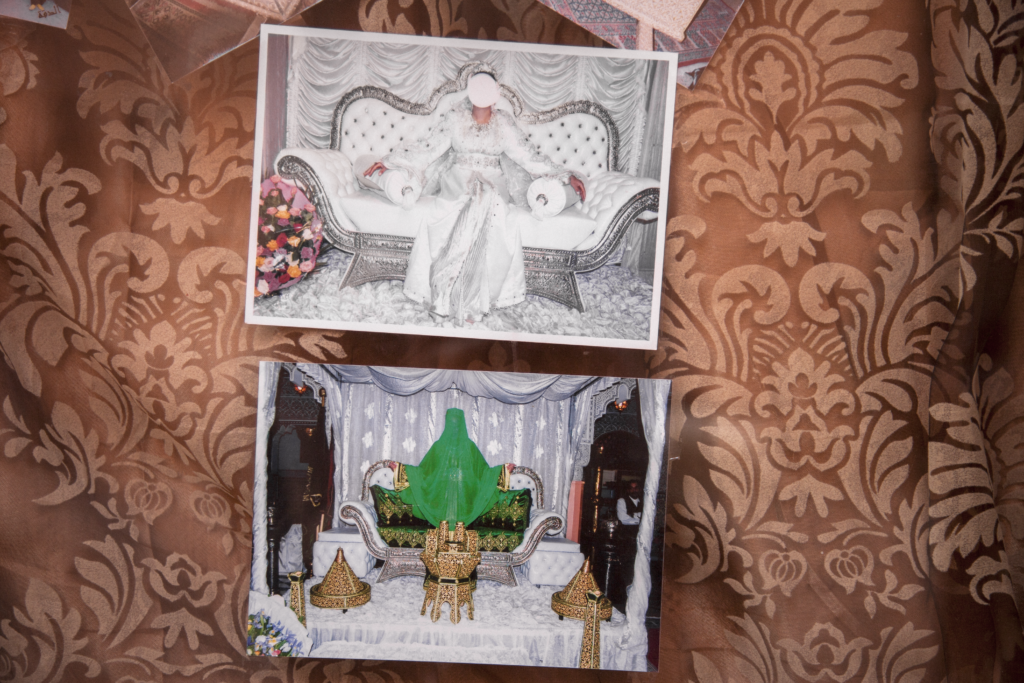

Window of wedding photographer studio, Marrakech, Morocco, 2013

Of all the challenges this project posed, this one was the most deeply uncomfortable for Meiselas. But rather than find a pictorial workaround, she decided to confront her discomfort head on. Meiselas generally works alone, focusing intently on her subjects and developing a relationship with them over time. In Marrakech she came to rely heavily on two young Moroccan women, Imane Barakat and Laila Hida, who became welcome and vital collaborators. With their help, Meiselas began to interview women in the spice market, questioning them directly about their reluctance to be photographed. Their answers were a surprise: it was not an issue of modesty or religious custom, as Meiselas had assumed. The women simply wanted to be paid.2

Photo booth set up in spice market, Marrakech, Morocco, for the 20 dirhams or 1 photo? project, 2013

The women of the Middle East and North Africa have long been tantalizing subjects for artists. As European colonial interests in the region grew, so did the appetite for images of the “Orient.” Such pictures rarely depicted the area or its inhabitants as they were, but rather reinforced European fantasies of an exotic, unchanging imaginary. The Romantic painters depicted the women of the “Orient” as languid creatures who lived in harems. Early photographers followed on those painters’ heels, supplying a new mass market with images of foreign places and people in strange and alluring costume, especially women. Their veils, worn out of tradition and by religious dictate — and not infrequently at the request of the artist — became for some audiences symbols not of modesty but of seduction. Though they should have been abandoned long ago, many of these stereotypes nonetheless persist, and now every tourist visiting the souk is armed with a camera. It is small wonder that after a century of being framed through others’ eyes that the residents of Marrakech had had enough.

Women from the spice market seeing themselves in the exhibition of 20 dirhams or 1 photo?, Marrakech Museum for photography and Visual Arts, 2013

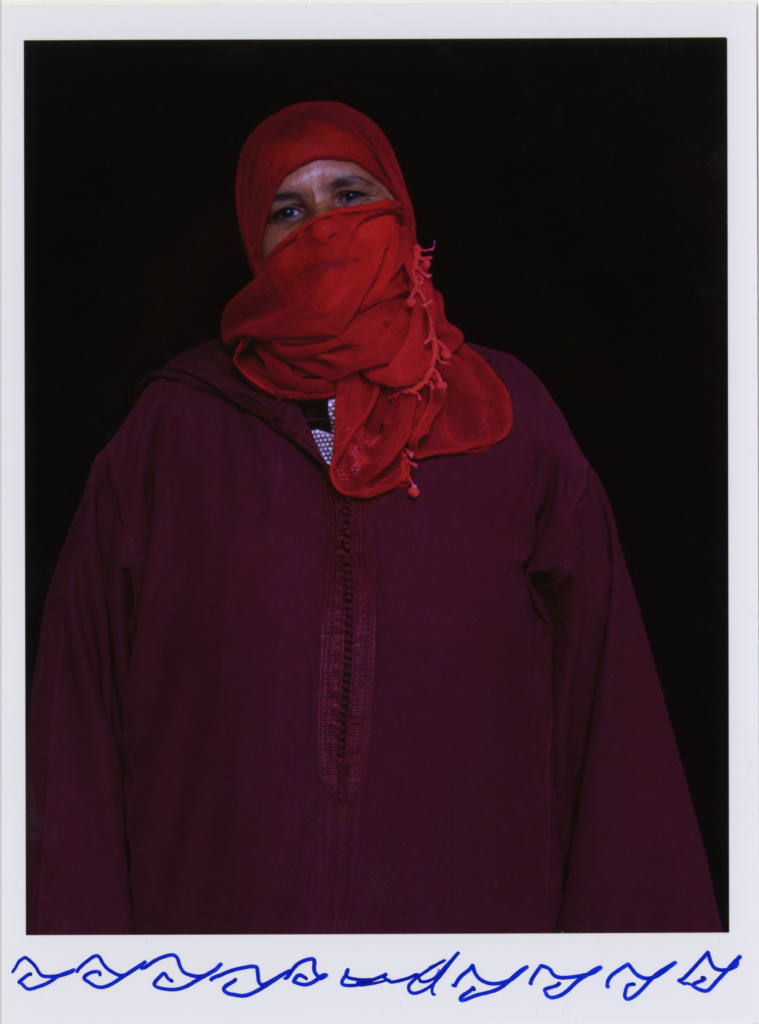

In the spice market, Meiselas sensed an opportunity to open a dialogue about the value of imagery, in both monetary and symbolic terms. As the week drew to a close, she expeditiously set up a pop-up studio in the market and invited the women who worked nearby to pose. Seventy-eight women and girls chose to participate, presenting themselves to Meiselas’s camera as they had come dressed for work that day. Veiled or unveiled, smiling or serious, the women looked into her lens with frank directness. There was one condition, however: before being photographed, the sitters had to decide if they wished to keep their portrait or be paid 20 dirhams in exchange for allowing Meiselas to keep the photograph and include it in the exhibition. Twenty dirhams is a modest sum, the price of a utilitarian identity photo in Marrakech. By choosing an amount associated with a routine and unremarkable purchase, Meiselas shifted the significance of the exchange away from financial gain, and centered it firmly on the question of agency. Sixty women opted to be paid and to have their likenesses on view at the museum. The other eighteen chose to keep their portraits. In their place, Meiselas exhibited 20 dirham notes, both commemorating the exchange and providing a concrete symbol of their encounter.

Signed portrait, Marrakech, Morocco, from the project 20 dirhams or 1 photo?, 2013

In cultures across the globe and across history, the marketplace offers a social hub, a site of encounter and exchange. Before nearly every household owned a camera, itinerant photographers often chose the market as an ideal place to attract clientele. In her own marketplace studio, Meiselas subtly transformed the act of photography from a unilateral act of taking a picture to one of conversation and empowerment. Her portrait of the city poignantly acknowledges complex questions about the right to be seen (or not), or to control one’s image, and shines a light on the charged relationship between looking and power.

Meiselas posed herself the question: Within the constraints of the project, how could she make a contribution?

Notes

- Interview with Kristen Lubben in Susan Meiselas: In History, ed. Kristen Lubben (New York: International Center of Photography, 2008), 16.

- It should be noted, however, that at the exhibition of 20 dirhams or 1 photo?, the topic of whether it was proper for women’s photographs to be displayed publicly was rather hotly debated among some of the exhibition visitors.