Excerpted from Clément Chéroux, “The Art of the Oxymoron: The Vernacular Style of Walker Evans,” in Walker Evans (Paris and New York: Centre Pompidou and DelMonico Books•Prestel, 2017), 8–14.

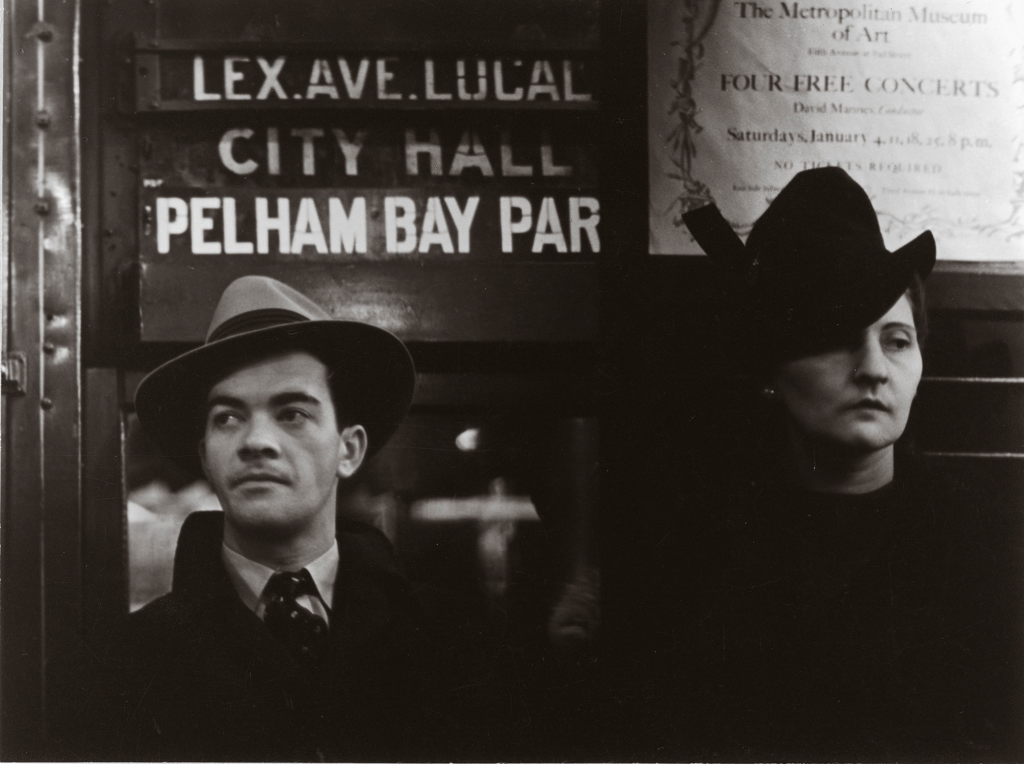

1. Walker Evans, Subway Portrait, 1941; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; gift of Kent and Marcia Minichiello, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A man and a woman sit side by side on the New York subway (fig. 1). He wears a light, wide-brimmed felt hat and a polka-dot tie. A sign above his head indicates that he is traveling on the Lexington Avenue line, which connects City Hall to Pelham Bay Park. She wears dark clothes and a somewhat tattered hat. Behind her is a poster for four free concerts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Both of them are absorbed in their thoughts. Looking more closely at the picture, several details attract our attention. She seems abnormally taller, or as if seated a little higher than he. A black vertical stripe that merges with the dark wall of the car divides the frame from top to bottom, at three-fifths of the image. A few years ago, Sarah Greenough, curator of the photography collection at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, which owns this rare Walker Evans print, noted that it is not one but two images.1 The subjects do not seem to be sitting at the same level because they are not in the same photograph. The black bar that appears on the print is actually the area separating the two successive views on the negative. When printing, Evans did not center his 35mm filmstrip (fig. 2) in the enlarger window, but instead offset it laterally so that the film holder could frame two consecutive shots. So he printed the right part of one image and the left part of the next one on the same photographic paper.2 Although they appear to be in the car at the same time, the two passengers had not been photographed at the same time. He belongs to the moment before, while she inhabits the one that follows. A photograph is usually perceived as a coherent whole in space and time. Evans’s image breaks out of this logical synchrony. Like a photomontage created in the very material of the film, it offers a diachronic reconstruction of the situation.

2. Walker Evans, Subway Passengers, New York City, 1941; © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Walker Evans Archive

This book and the exhibition it accompanies are constructed according to this same diachronic principle. Most retrospectives of Evans’s work are chronological: the modernist beginnings, the trip to Cuba, the work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the series on the three families of Alabama sharecroppers, and then the portfolios for Fortune magazine. With the exception of its introduction devoted to Evans’s early years, this project breaks with chronology, mixing times and places from a decidedly more thematic perspective. This approach has several advantages. It allows us to better understand what might be considered a stretching or a dispersal in Evans’s work. The subway portraits, for example, were taken between 1938 and 1941, but the series did not take its final form until 1966, through an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, and the publication of the book Many Are Called.3 Those who approach the work chronologically generally position this series in either the 1930s or the 1960s—in other words, either as a continuation of the exploration of the human face begun in Alabama or in the context of the more conceptual projects done for Fortune. However, as in the example of the photograph described in the introduction, this project combines the two. The thematic analysis solves this dilemma and renders the complexity of the project. It also provides an opportunity to more clearly link photographs separated by time or space and thus bring to light Evans’s true preoccupations with certain subjects, like shop windows and typographic signs, which he never stopped compulsively hunting from the beginnings of his career in the 1920s to his death in 1975. Finally, approaching Evans’s work through its most recurrent themes makes it possible to better grasp what constitutes its core: the passionate search for the fundamental characteristics of American vernacular culture.

The word vernacular is composed of the Latin root verna, meaning “slave.”4 Under ancient Roman law, slaves were considered property. Aristotle defined a slave as a “living tool.”5 The vernacular defines an activity linked to servitude or at least to service; it is utilitarian. In Roman law, vernaculus more specifically described a person who was not a product of the slave trade. He was not purchased or exchanged, but was born at home. By extension, the vernacular includes everything that is made, grown, or raised at home. It corresponds to domestic or homemade production. This is the reason that the vernacular is often associated with things local or regional. Finally, the slave occupied the lowest rung in the social hierarchy. Likewise, on the scale of cultural values, the vernacular has been designated a minor position. It is always located below what has been recognized as most worthy of interest by arbiters of culture. It develops on the periphery of what is considered to be standard, to count, or to carry weight in establishing taste. Decidedly popular, more linked to the culture of the masses than the elites, it is the alternative to fine art. Vernacular is one of those intimidating words we do not dare use without quotes. It always seems too broad for what it describes . . . or not precise enough. Its meaning seems to vary depending on who is using it. Here, it is defined from three specific angles: function, place, and spirit. The vernacular is useful, domestic, and popular.

The vernacular occupies a central place in American culture. It is found in literature as early as the nineteenth century, but it was not until the late 1920s that it became the subject of the first theoretical construct in the field of architectural studies. At Harvard University, in the magazine Hound & Horn, and during the early days of MoMA, personalities like Lewis Mumford, Alfred Barr, Lincoln Kirstein, Philip Johnson, and Henry-Russell Hitchcock set out to demonstrate that the United States played a role in the development of modernism through its regional or functional architecture.6 In 1934, Hitchcock along with photographer Berenice Abbott organized the exhibition The Urban Vernacular of the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties: American Cities before the Civil War.7 Not devoid of nationalistic ambitions, the project was intended to Americanize modernism through the lens of the vernacular. However, the term was little used in the 1930s. It was not until the work of American scholar John Atlee Kouwenhoven in the ensuing decade that the word started to migrate from the field of architecture to that of culture. In fact, it was he who would reintroduce the concept into the discussion of American art. Born in 1909, Kouwenhoven began taking an interest in the vernacular in 1939. He published his initial theories on the subject in August 1941 in the Atlantic Monthly, and then delved more deeply into them in his doctoral thesis at Columbia University, which culminated in 1948 in the publication of his seminal book Made in America: The Arts in Modern Civilization.8 He returned to these topics frequently throughout his collections of essays The Beer Can by the Highway (1961) and Half a Truth Is Better Than None (1982).9

Kouwenhoven’s understanding of the vernacular matches the one defined above: according to him, too, it is useful, domestic, and popular. He analyzes it, however, from a uniquely American point of view, that is, in a decidedly more positive and pragmatic way, one no longer linked to slavery. The main quality of the vernacular is therefore not servitude, but rather serviceability. Furthermore, from its utility, Kouwenhoven derives a particular quality that he describes as a “Truth of Function.”10 To explain this, he cites the example of tools manufactured in the United States, which are less ornamental, simpler, and more efficient than those manufactured in Europe. According to him, there is in the American vernacular a sort of functional beauty. In the scholar’s essays, vernacular culture is also domestic, but in a much broader sense. By shifting the production process from the home to the factory, the Industrial Revolution brought about an expansion of the concept. The vernacular was no longer solely homemade or handmade, but could also be factory made. It no longer simply referred to the production of a region, but to that of an entire country. In the industrial era, it was the nation that now acted as the home. While in Europe the vernacular had largely contributed to the formation of regional cultures, in the United States it participated fully in the development of a national identity. To explain this, Kouwenhoven often cites the example of the Ford Model T, which, for the era, represented not only maximum optimization of the industrial production process, but also acquisition of a self-sufficient means of transportation for the masses. It was, he felt, a perfect example of the American industrial vernacular.

Notes

- See Sarah Greenough, Walker Evans: Subways and Streets (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1991), 38.

- This was not simply a laboratory experiment, as the photographer would publish this image in “Walker Evans: The Unposed Portrait,” Harper’s Bazaar, March 1962, 23. It was also shown at the 1966 MoMA exhibition.

- Walker Evans’ Subway, 1938–1941, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 5–December 11, 1966; Walker Evans, Many Are Called (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966).

- See Alain Rey, ed., Dictionnaire historique de la langue française (Paris: Le Robert, 2010), 2437; Marguerite Garrido-Hory, “Verna,” in Des formes et des mots chez les Anciens: Mélanges offerts à Danièle Conso, ed. Claude Brunet (Besançon, France: Presses Universitaires de Franche-Comté, 2008), 299–308.

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 8:11.

- See Mardges Bacon, “Modernism and the Vernacular at the Museum of Modern Art, New York,” in Vernacular Modernism: Heimat, Globalization, and the Built Environment, ed. Maiken Umbach and Bernd Hüppauf (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005), 25–52.

- See Janine A. Mileaf, Constructing Modernism: Berenice Abbott and Henry-Russell Hitchcock: A Re-creation of the 1934 Exhibition, The Urban Vernacular of the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties: American Cities before the Civil War (Middletown, CT: Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University, 1993).

- John A. Kouwenhoven, “Arts in America,” Atlantic Monthly 168 (August 1941): 175–80, and Made in America: The Arts in Modern Civilization (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1948).

- John A. Kouwenhoven, The Beer Can by the Highway: Essays on What’s American about America (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961), and Half a Truth Is Better Than None: Some Unsystematic Conjectures about Art, Disorder, and American Experience (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

- Kouwenhoven, “Truth of Function,” in Made in America, 16.