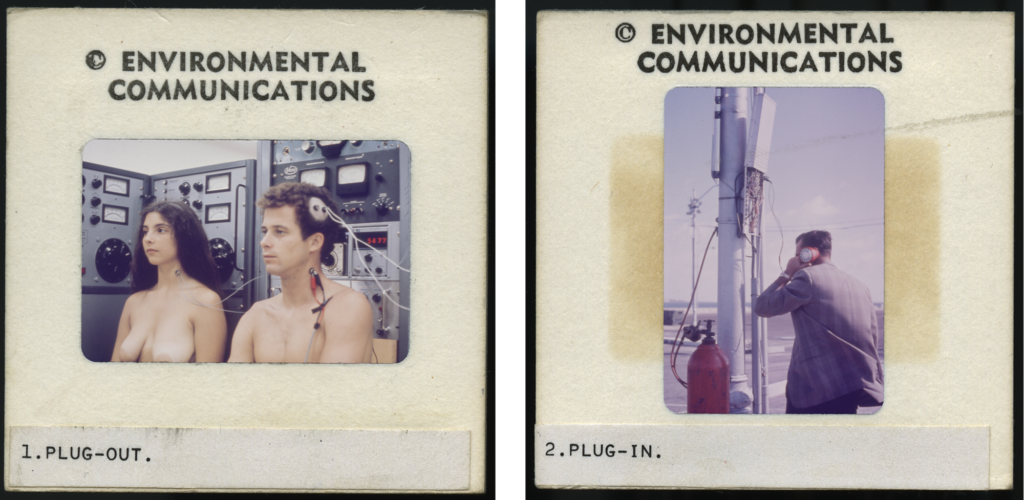

Ant Farm, selections from Beyond Things Past, 1971–72; collection SFMOMA, gift of Chip Lord and Curtis Schreier

Beyond Things Past (1971–72), a slideshow by the experimental architecture collective Ant Farm, opens with two depictions of the human-technology interface. The first centers on a nude woman and man, their bodies attached by a series of electric nodes to a computer array that promises a virtual window into their thoughts. In the second, a man in the staid attire of a Cold Warrior connects a telephone receiver to an open panel of wires, gaining access to an invisible communications network. These images of the reciprocal acts of “plugging-out” and “plugging-in” register a new awareness of the human relationship to technology, tinged by both a sense of possibility and an ironic skepticism verging on the parodic. Ant Farm’s project reflects a deep ambivalence about technology prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly within the counterculture in which the group were famous participants. Those taking issue with the status quo saw technology as an engine in the production of a militarized culture and repressed subjects. At the same time, many of these critics were also drawn to digital tools as a means of personal and collective liberation.

In hindsight this anxiety and excitement seem equally appropriate. Technological developments of recent decades have ushered in fundamental transformations in contemporary life. As physicist Ursula Franklin notes in The Real World of Technology, “There seems to be a very drastic change in what it means today to be human—what it means to be a woman, a child, a man; to be rich or poor; to be an insider or an outsider.”1 The works assembled in Designed in California attest to the state’s role as a laboratory for these changes in technology and living, with its universities, corporate offices, design studios, and homes serving as experimental sites for prototyping possible futures. The scope and speed of these recent technological developments illustrate how deeply the design of tools shapes our day-to-day life and informs the kinds of subjects we become.

This of course is not unique to the digital age; objects and daily acts have always contributed to the definition of selves. As novelist Ursula K. Le Guin notes, whether “hi” or “low,” digital or analog, “Technology is the active human interface with the material world.”2 Philosopher Michel Foucault argued that all technologies imply “modes of training and modification of individuals.”3 These realizations have recently been echoed by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, who note that the emergence of the human coincides with the invention of the tool; the human is a fundamentally “prosthetic being” constituted through her external supports.4 In any era, “design is always the design of the human.”5

However, the degree, pace, and breadth of recent innovations have had consequences that exceed many previous periods of technological change. The nature of these transformations is also more centralized and controlled by fewer interests than ever before. This scenario poses crucial questions for both citizens and designers. What kinds of selves do contemporary technologies produce? And what is the role of designers and users in ensuring that technology supports our collective interests?

The Wired, the Cyborg, the Database

At the same time Ant Farm assembled their unorthodox images, Charles and Ray Eames offered a more mainstream vision for the integration of man and machine in their film Cable: The Immediate Future (1972). Sponsored by the National Science Foundation and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the film centers on the implications of cable technology. The future it depicts is crucially dependent on the computer’s ability to render cable communications “two-way,” coordinate sophisticated content delivery, and collect data. Examining cable as an information infrastructure whose affordances have yet to be fully exploited, the Eameses envision a cashless, checkless society, electronic mail delivery, community forums, and wired cities enabled by an intensification of digital information exchange.

Charles and Ray Eames, stills from Cable: The Immediate Future, 1972; © Eames Office, LLC / eamesoffice.com

The film opens with a broad discussion of cable and its potential and goes on to explore the domestic life of a stereotypical American family whose lives have been refigured by a “wired home.” From sensors that monitor the family while they sleep to the on-demand delivery of news tailored to their preferences, the scene has proven remarkably prescient. However, while the film imagines a new domestic landscape afforded by technology, it is decidedly normative and nonthreatening in its depiction of the social relations that the wired home will support, assuaging fears that changes to technology will entail fundamental changes to selves. Though the means may be modified, the film implies that the essential nature of daily life will remain intact. A housewife still picks up the mail, prepares breakfast, and shops (though now via her television) and a husband still works with his uniformly male colleagues (if at home via teleconferencing). In this sense, the film is typically Eamesian, grounding a narrative of the new in what is already familiar.

Lisa Krohn, Cyberdesk, 1993; collection SFMOMA, gift of the artist; photo: Ian Reeves and Katherine Du Tiel

While Cable emphasizes continuities of living amidst technological change, other designers have embraced the ways in which new tools bring about new kinds of selves. Lisa Krohn’s visionary prototype for Cyberdesk (1993) celebrates the intimacy between subjects and their tools afforded by miniaturized mobile technology. In her vision a metal and silicone assemblage—part jewelry and part control center—is grafted onto the body, eliminating any clear boundary between user and device. Krohn’s approach evokes the broader excitement about the figure of the cyborg in the 1980s and 1990s. Feminist scholar Donna Haraway famously theorized the cyborg as the ultimate boundary crosser, a figure who achieves liberation from traditional norms by transgressing barriers, key among them the divisions between human and technology, nature and culture. For her, “high-tech culture” was crucial in destabilizing assumed understandings of what it is to be human, noting that “it is not clear who makes and who is made in the relation between human and machine.”6 In Haraway’s account this is not a source of fear but a tool for creating new, more inclusive ways of living; she wonders: “Why should our bodies end at the skin?”7

What was framed in the language of science fiction in the 1980s has become real. We are accustomed to the sensation of silicone on skin, in the form of earbuds, self-trackers, and other devices that link our bodies to information networks. A future where technology and the body are fully integrated is now within view. In their concept for Project Underskin, the Near Future of the Wearable (2014), NewDealDesign forecasts a wearable that disappears into flesh, becoming visible at moments where our security, movement, wellness, or self-expression require digital support. Such technologies promise to monitor our health, manage our homes, and connect to people and information. They also influence the ways we understand and articulate our identities. As Boris Groys has argued, “In our time self-design has become the mass cultural practice par excellence,” broadcasting our taste but more crucially distributing aspects of ourselves across information networks.8

NewDealDesign, Project Underskin, 2014; courtesy NewDealDesign, LLC

These developments can be correlated with the rise of a new kind of self. Anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll describes this as the “self as database,”9 a subject who constantly generates, collects, and analyzes personal data through smart devices in ways that evoke the “administrative view” of one’s own life analyzed by Foucault10 and conform to the contemporary mantra, “You are your data.”11 As both Dow Schüll and Groys point out, this new self is split into many pieces, constituted through a dispersed database of snapshots and impressions. The body is reframed as a “data-generating device” and any boundaries between real and virtual selves become difficult to distinguish or maintain.12

The Immediate Future

Dow Schüll observes that the “self as database” relies on continual surveillance and care of the self. We allow ourselves to be watched, regulated, and registered in the interest of remaining fit, secure, and connected, “blurring . . . the line between control and self-control.”13 Technologist Ian Bogost offers the concept of “hyperemployment” to characterize the constant action and anxiety triggered by such connected living.14 In a similar vein, media scholar Lynn Spigel points to the way that smart homes promising personal freedoms also create an expectation of uninterrupted productivity, intensifying consumption and often perpetuating traditional gender roles.15 Though we may increasingly resemble Haraway’s cyborgs, we are now faced with the reality that human integration with technology can reinforce social and economic norms as much as it transgresses them.

As Designed in California argues, today’s developments echo tensions between liberation and control that have long been at the heart of design emerging from California. While the contemporary moment may seem to pose radical challenges, the question of whether technology facilitates new futures or perpetuates norms was present when Ant Farm juxtaposed their scenes of countercultural transgression and technocratic management enabled by machines. As Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron note, the state’s central role in the design of new technologies presents a paradoxical fusion of “the disciplines of market economics and the freedoms of hippie artisanship”—what they term the “Californian Ideology.”16 Beneath this ideology, they argue, lie unanswered questions about the ownership and management of digital resources, the crucial role of government support and DIY initiative in ostensibly private innovation, and deep inequalities in the state despite the promises of technoutopianism. The persistence of these tensions decades into the digital revolution underlines the ultimate ambivalence of information technology. Digital tools are neither progressive nor oppressive by nature but rather take on their significance through collective and individual acts of design and use.

The Eameses predicted the far-reaching implications of information technologies in Cable, underlining the “considerations of privacy” raised by developments like the wired home. Yet they also looked beyond simple concerns with privacy and surveillance, posing the more expansive question, “Who will have access to the media and who will be in control?” They explain that the future of information technologies “is being written now in boardrooms, in franchise hearings, sometimes behind closed doors.” Cable ends by calling for civic engagement and collective debate about our desired relationship to technology, echoing the Eameses’ consistent argument that design must be attentive to “the concerns of society as a whole.”17

Franklin calls for such debates early in the course of technological change, noting that:

The early phase of technology often occurs in a take-it-or-leave-it atmosphere. Users are involved and have a feeling of control that gives them the impression that they are entirely free to accept or reject a particular technology and its products. But when a technology, together with the supporting infrastructures, becomes institutionalized, users often become captive supporters of both the technology and the infrastructures.18

The risk of such inertia increases as ownership of technological interests becomes further concentrated in fewer hands and as digital infrastructures grow increasingly opaque, proprietary, and difficult to map. This magnifies the implications of the work of technologists and designers, whose choices can have outsized impacts on collective realities.

Franklin goes on to note that “the viability of technology, like democracy, depends in the end on the practice of justice and on the enforcement of limits to power.”19 As anthropologist Nick Seaver argues, it is wrong to view contemporary digital technologies as external forces that “disrupt” culture. Technology is the product of human practices and as such can be subjected to “dispute and potential regulation.”20

That the primary site of technological change might be our own bodies and minds may be disconcerting. However, if Haraway is correct in observing that we make technology as much as it makes us, present day cyborgs may yet have the capacity to design relationships with technology that bring about progressive social change, embracing the malleability of the human to design more just subjects and societies. We might start by asking who we want to become through our interaction with digital tools.

For more on the history and future of California design, visit Designed in California through May 27, 2018. And to learn about the intersections of design and technology, register for Access to Technology: California Design Today, an SFMOMA 101 course engaging the exhibition’s themes through a series of conversations with curators and scholars.

Notes

- Ursula Franklin, The Real World of Technology (Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 1999), 4.

- Ursula K. Le Guin, “A Rant About ‘Technology,’ ” accessed January 29, 2018, https://www.ursulakleguin.com/Note-Technology.html.

- Michel Foucault, “Technologies of the Self,” in Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault, eds. Luther H. Martin et al. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 18.

- Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, Are We Human? (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016), 75.

- Colomina and Wigley, 205.

- Donna J. Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), 177. For more on the coproduction of user and technology, see Bill Maurer, “Principles of Descent and Alliance for Big Data,” in Data: Now Bigger and Better!, eds. Tom Boellstorff and Bill Maurer, (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2015).

- Haraway, 178.

- Boris Groys, “Self-Design, or Productive Narcissism,” e-flux Architecture, September 22, 2016.

- Natasha Dow Schüll, “Data for life: Wearable technology and the design of self-care,” BioSocieties (11:3, 2016), 8.

- Foucault, 33.

- Dow Schüll, 9.

- Dow Schüll, 10.

- Dow Schüll, 10.

- Ian Bogost, The Geek’s Chihuahua: Living with Apple (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

- Lynn Spigel, “Designing the Smart House: Posthuman domesticity and conspicuous production,” European Journal of Cultural Studies (8:4, 2005), 403–26.

- Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, “The Californian Ideology,” Science as Culture (6:1, 1996), 50. For a rich account of the intersections of technology and counterculture, see Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

- Charles Eames, “‘What is Design?’: An Exhibition at the Louvre,” in An Eames Anthology: Articles, Film Scripts, Interviews, Letters, Notes, Speeches, ed. Daniel Ostroff, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 282.

- Franklin, 95.

- Franklin, 5.

- Nick Seaver, “Algorithms as culture: Some tactics for the ethnography of algorithmic systems,” Big Data & Society (July–December 2017), 5.