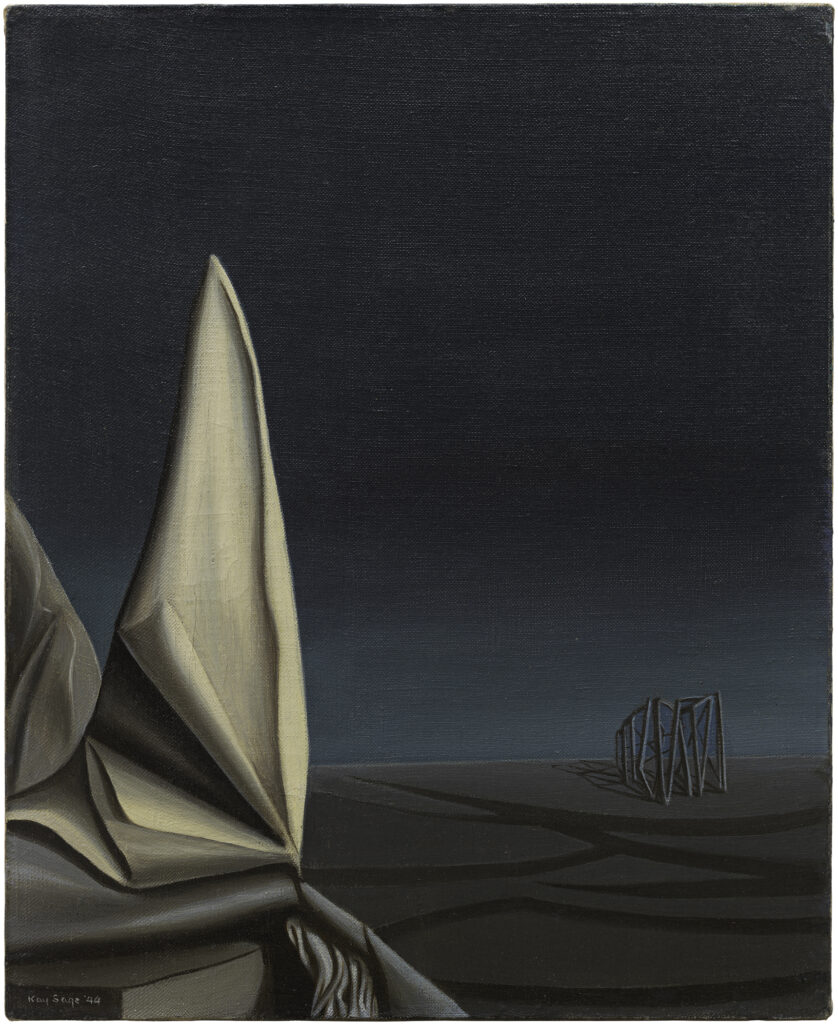

Kay Sage, Midnight Street, 1944; oil on canvas; 16 × 13 in. (40.6 × 33 cm); Purchase, by exchange, through a gift of Peggy Guggenheim, 2019; ©️ Estate of Kay Sage / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kay Sage was not inclined to explain her paintings. When asked about one of her works, she famously said that she knew “nothing of [its] origin except that I painted it.”1 There was, however, a certain observation that she readily made: “I do know that while I’m painting I feel as though I were living in the place.”2 The curious landscape of Midnight Street (1944) is such a place. Sage pushed the objects that inhabit this domain to its margins, emphasizing the sky, the earth, and the cool, crisp atmosphere. Like many of her paintings, Midnight Street is less an image to interpret than a world to inhabit.

Sage used exacting illusionism to bring this phantasmal terrain to life. Her delicate modeling grants each form convincing detail, while exaggerated perspective creates depth and distance. The extreme shift in scale and value between the white form in the foreground and the structure in the background turns the ground into a yawning expanse, and shadows emerging from the right imply a large object out of frame, extending this environment beyond the edges of the canvas.

Sage had refined these illusionistic techniques within the confines of the beaux-arts system. Born Katherine Linn Sage in 1898 to a wealthy family in Albany, New York, she grew up worlds apart from the bohemian circles of the avant-garde. Her father, a New York state senator and heir to a lumber fortune, paid for Sage’s classical art education at various American and European institutions. She later described the art scene in Rome, where she received much of her early training, as “hopelessly academic.”3 In 1927 Sage married the Italian prince Ranieri di San Faustino, and for ten years she virtually abandoned painting to the social demands of high society.

Upon leaving her husband and moving to Paris in 1937, however, Sage encountered work by the Surrealists and their precursors, many of whom used illusionism in radical new ways. She saw paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, who shared her abiding fascination with perspective, distant horizons, and long shadows. She also saw the paintings of Yves Tanguy, whose biomorphic figures on foggy tundra soon found parallels in her own work. These artists drew on the imagery of dreams and the unconscious to create realistic worlds of wildly unrealistic subjects. Sage absorbed the sense of mystery and fantasy in their work and soon became a strong presence in the Surrealist movement. Within three years she and Tanguy were married and in the midst of a coterie that gathered around the movement’s ringleader, André Breton.

Midnight Street typifies Surrealism’s combination of the lifelike and the inexplicable. Forms seem to resemble objects in the real world—a sail in the foreground and scaffolding in the background—but do not quite fulfill these roles. The sail unfolds along a peculiar seam that denies its function, and the scaffolding buckles unevenly. The painting demonstrates Surrealism’s guiding interest in the uncanny—the familiar made strange—and the hovering ambiguities of dream imagery.

Yet while Tanguy and others filled their paintings with creatures and forms, Sage often left her landscapes unpopulated, stressing instead the panoramas of an alien hinterland. As a young artist, she had studied with the landscape painter Onorato Carlandi, joining him on excursions to paint the wide valleys of the Italian countryside. “I think my perspective idea of distance and going away is from my formative years in the Roman Campagna,” she later said.4 Midnight Street shares the light, atmosphere, and expanse of landscape painting. Deep browns and blues impart the chilliness of twilight, and long shadows suggest a setting sun. Like Dutch landscapes of the Northern Renaissance, her composition frames an enormous expanse of sky. With the territory itself as her focus, Sage did not so much conjure dreams as dreamscapes—the places in which dreams happen.

Midnight Street suggests a desolate dream, and it is tempting to read loneliness into the work. Indeed, Sage began to paint in this way only after the deaths of her father and her sister in the early 1930s and her later divorce. However, the emptiness of Midnight Street might also convey Sage’s fierce independence. Her personal writings reveal a resolve for privacy. In her poem “The Window,” she writes:

My room has two doors

and one window

One door is red and the other is gray.

I cannot open the red door;

the gray door does not interest me.

Having no choice,

I shall lock them both

and look out of the window.5

As the daughter of a wealthy senator and the wife of a hobnobbing prince, for many years Sage had been forced to play the role of refined debutante. Her dreamscapes may have represented an escape from such tiresome mingling. She often recalled a saying from her teacher Carlandi: “If you are alone, you will be completely yourself.”6 Perhaps she painted places of solitude for this reason—as windows onto a world of her own.

Notes

- Kay Sage quoted in Mara R. Witzling, “Kay Sage,” in Voicing Our Visions: Writing by Women Artists, ed. Mara R. Witzling (New York: Universe, 1991), 234.

- Kay Sage quoted in “Serene Surrealists,” Time, March 13, 1950, 49.

- Kay Sage, “Excerpts from China Eggs, 1955,” in Voicing Our Visions, 239.

- Kay Sage quoted in Stephen Robeson Miller, “In the Interim: The Constructivist Surrealism of Kay Sage,” in Mary Ann Caws, Rudolf E. Kuenzli, and Gwen Raaberg, eds., Surrealism and Women (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991), 129.

- Kay Sage, “The Window,” in Voicing Our Visions, 247.

- Kay Sage quoted in Miller, “In the Interim,” 129.