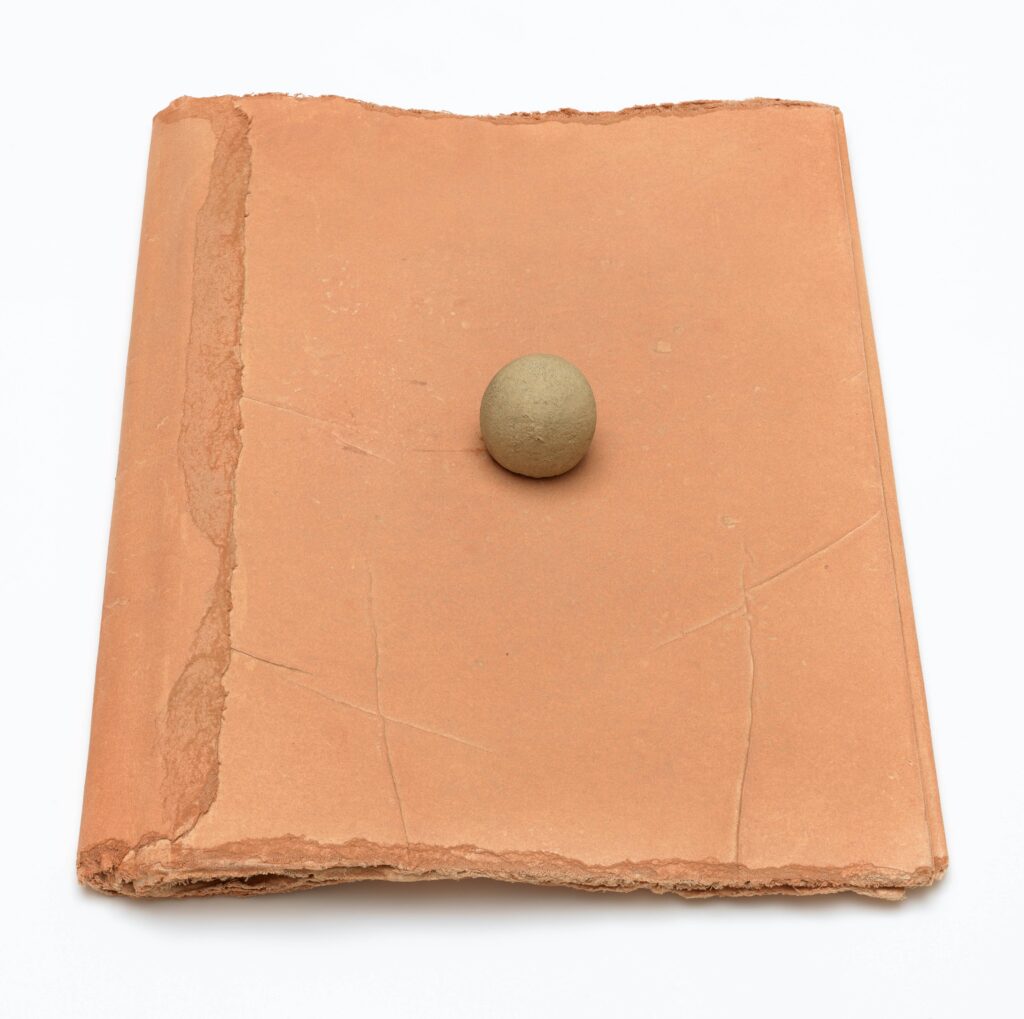

Michelle Stuart, Spiral Notebook, 1975; earth and stone on paper mounted on muslin, 13 × 9 × 2 in. (33 × 22.9 × 5.1 cm); anonymous gift in honor of Gary Garrels, 2019; © Michelle Stuart

“How better to know a place than to know the earth of a place?” the artist Michelle Stuart once asked.1 Since the 1970s, Stuart has traveled around the world, exploring sites where history and geology intertwine. For Spiral Notebook (1975), she took earth from the region around the sovereign nation of the Jemez Pueblo—known to Pueblo members as Walatowa—crushed it into a large sheet of heavy paper, and then folded this paper to form a book. The work brings to mind the adobe bricks that have been used in the Southwest for thousands of years, and its encrusted pages evoke a written history of this region told through the land that built it.

To make this sculpture, Stuart traveled an hour northwest from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to the Jemez Pueblo area and worked outdoors among its rock formations. She adhered to the same process that she used in many of her pieces: “I beat the rocks and earth into the surface fibers of the paper and rubbed the residue continuously until the paper was imbued with earth.”2 The surface becomes rich in color and texture, mottled with scratches, pleats, and indentations that capture what Stuart once called “the handwriting of nature.”3 This handwriting is specific to each work: “Each place has rocks that have their own personality or configuration, each rock leaves its own mark.”4 In this way, Spiral Notebook is an index of the region’s distinctive constitution.

Stuart also inscribed the work with her own presence. Blending rock and paper requires vigorous rubbing, kneading, beating, and scouring. Sweat from Stuart’s palms, oil from her fingers, and even blood from cuts and scratches fuse with the pulverized earth. Crude circular shapes across Spiral Notebook’s pages trace the rhythms of her movements. The overlapping of her mark-making with other impressions forms a new “handwriting” of place—not of the artist or of the land, but of their interaction.

Spiral Notebook also summons a deeper, ancestral connection with the earth. New Mexico claims one of the world’s longest traditions of building with compressed earth, known as adobe. Some of its adobe structures date back ten thousand years. By the time European colonists reached the area in the sixteenth century, the Jemez Nation comprised an estimated forty villages constructed from the material. Europeans imitated adobe construction techniques learned from Native American builders, which led to the development of a distinctive style of architecture known as Pueblo or Pueblo Revival. New Mexican adobe has since become a large-scale industry in the Southwest. While the original villages of the Jemez Nation have now disintegrated—in no small part due to colonial oppression that forced tribe members into a single village—adobe remains a living tradition, maintained through Indigenous practices and altered through its appropriation by white people.

Stuart draws our attention to these layers of history. The marks and clots on Spiral Notebook form layers of inscription, conjuring what Stuart has called “the overlay and the imprinting of one culture upon another.”5 Its caked pages recall sediments of bedrock, like chapters in this history. On top of the book is a tufa stone from the igneous mountains around the Jemez Pueblo region, made of compressed volcanic ash—a handful of dust that has congealed, dissolved, and congealed again over millennia. Spiral Notebook suggests similar cycles of erosion and petrification, holding centuries of earthly and civilizational change within its monochrome surface.

The art critic Lucy Lippard, Stuart’s friend and collaborator, once offered a definition of place: “Place, of course, as opposed to the more generalized ‘site’ or ‘land,’ is a specific collaboration between nature and people, constantly altered and inevitably defined by narratives from the contact zones.”6 Stuart’s sculpture embodies this sense of place. Like an adobe builder, she collaborates with the earth, and like a colonist, she pulverizes it. Spiral Notebook becomes a “contact zone”—a place made through this interaction.

Notes

- Michelle Stuart quoted in Carol Kino, “A Cosmos of Matter, Enshrined in Her Art,” New York Times, August 30, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/30/arts/design/michelle-stuarts-work-at-the-parrish-art-museum.html (accessed December 18, 2019).

- Michelle Stuart in Michelle Stuart: Sculptural Objects (Milan: Charta, 2010), 33.

- Michelle Stuart quoted in Lucy R. Lippard, “Touchstones,” in Michelle Stuart: Sculptural Objects, 9.

- Stuart quoted in Lippard, “Touchstones,” 9.

- Michelle Stuart quoted in Anna Lovatt, “Palimpsests: Inscription and Memory in the Work of Michelle Stuart,” in Lovatt, Michelle Stuart: Drawn from Nature (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2013), 14.

- Lippard, “Touchstones,” 11.