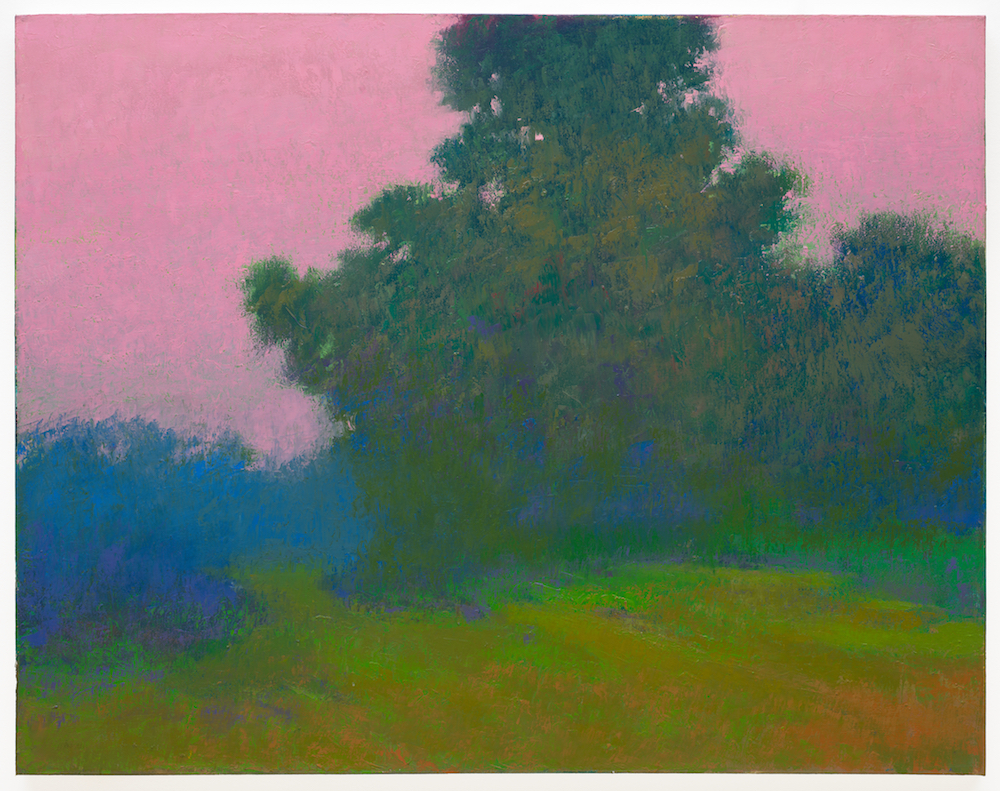

Richard Mayhew, Delusions, 2000; oil on canvas, 30 × 40 in. (76.2 × 101.6 cm); Gift of The Pamela J. Joyner and Alfred J. Giuffrida Collection, 2017; © Richard Mayhew

“I’m painting Forty Acres and a Mule,” Richard Mayhew has said of his landscapes, referring to the land parcels and livestock promised but never granted to freed slaves after the Civil War. “I’m painting the treaty land that was never honored for Native Americans.”1 Drawing on his Afro-Native heritage, Mayhew’s paintings pose a challenge to America’s landscape tradition and its association with a long history of white colonial expansion. The luminescent scenery in Delusions (2000) may seem an unlikely protest against this tradition, but a close look reveals how Mayhew turns the conventions of landscape inside out and reclaims the wilderness for the dispossessed.

During the 1960s Mayhew joined Manhattan’s pioneering Spiral collective, a circle of black artists that formed in solidarity with the civil rights movement. In the decades that followed he became increasingly interested the Native American heritage of his Shinnecock grandmother. For Mayhew, these two legacies converged in a mutual respect for the land. “The land, the sky and the water, that’s it,” he has said. “The two cultures overlap in terms of the land being important to them.”2 That both groups were subject to the violent theft of territory only deepened this connection; in Mayhew’s words, “their blood is in the soil.”

Historically in the United States, landscape painting has often operated as a form of white prospecting. In the nineteenth century it was a way to visualize the Western Territories, justify their annexation, and sweep people of color to their margins. Many paintings of the Hudson River School, for example, shared an elevated perspective over sweeping vistas, conjuring the wonders that lay westward and eliciting fantasies of Manifest Destiny. The evocative use of light, cast dramatically upon the wilderness, implied a divine justification for white conquest. These depictions offered a vision of America unspoiled by the presence of others. Native Americans were often placed in the shadows, as part of the natural scenery, and slaves were rarely depicted at all. For Mayhew, this “omission” implied that as a brown person, “you don’t exist.”3

Mayhew recognizes the urgency of black and native perspectives on the land and reworks the genre’s conventions to counter the colonial gaze. In Delusions, he fixes his view on a small, uneven tract of earth as it recedes into brush, evoking the areas where black and indigenous Americans were consigned in pictures, as in life. Instead of positioning the viewer above this landscape, Delusions places us within it; our perspective is the same as that of the Native Americans painted in the underbrush of Hudson River School canvases.

Years before making this work, Mayhew visited a former plantation in Louisiana, where he was drawn to the humble plots around the slave quarters. Darkness buried in the underbrush gave these places what Mayhew calls a “mystique” or an ”area of feeling”—a ghostly presence of historical suffering, but also of immanent empowerment. The gauzy atmosphere of Delusions captures this mystique, transforming the modest territory into a place of spiritual awakening.

Mayhew’s approach to color and light challenges the way landscape painting historically sought dominion over nature. Delusions offers colors of contrasting hues but of correspondingly high saturation, making the composition hover with uncertainty as tones appear to blur. “I learned how to manipulate the eye,” Mayhew said. “The background’s coming forward and the foreground is receding.” Where landscape painting has often opened nature to visual seizure, here it eludes our gaze. Mayhew inverts the traditional use of light in a similar way. Instead of falling on the land to convey an authority over the wilderness, light radiates from within it. Mayhew daubs a brilliant blue in the darkest depths of his painting, as if an animating force exists beyond our reach.

The title of this painting, Delusions, remains open to interpretation. It could refer to the delusion of white ownership over a landscape that can never truly be possessed, or it could suggest the delusion of land justice for Native and African Americans. Stylistically, however, it captures the hallucinogenic ambiguity of this picture, which, instead of fixing nature in place, summons its ongoing transformations. For Mayhew, nature is protean and indefinable. If the Hudson River School laid claim to a wilderness, Mayhew transforms this wilderness into something unclaimable. Delusions is a spectral, spiritual landscape—a landscape that cannot be conquered.

Notes

- Richard Mayhew quoted in Janet Berry Hess, The Art of Richard Mayhew (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014), p. 72.

- Richard Mayhew, interview by the author, Santa Cruz, California, December 19, 2018. Unless otherwise noted, all following quotes are from this source.

- Mayhew quoted in Hess, The Art of Richard Mayhew, p. 70.