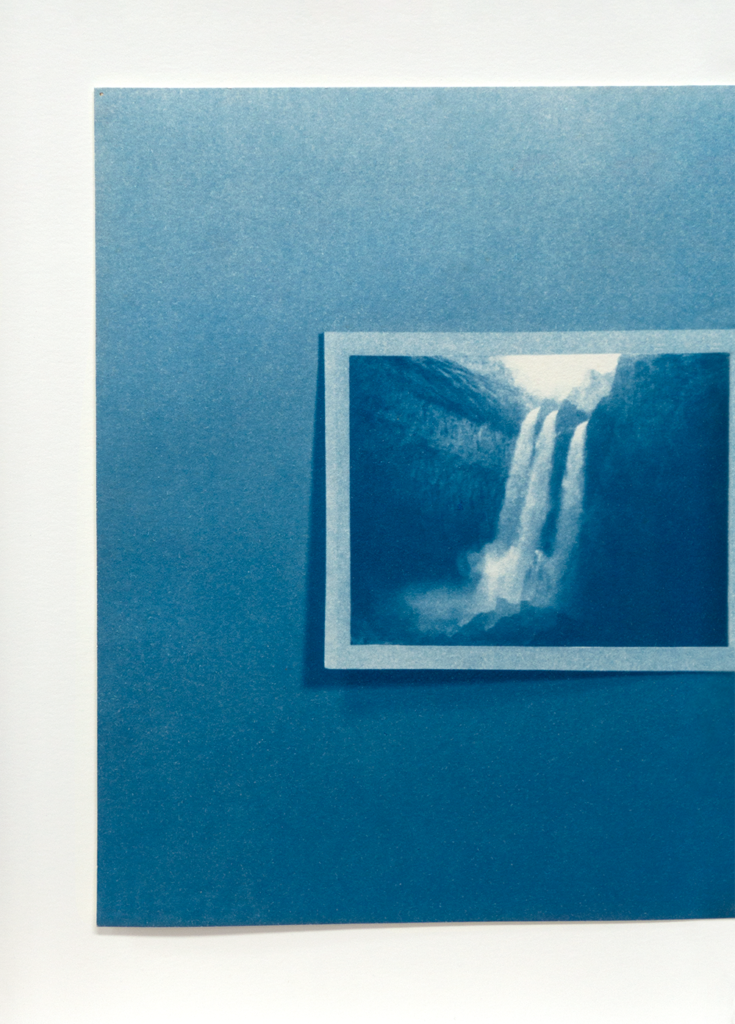

Sean McFarland, Three Falls (stand-in), 2014 (detail); courtesy the artist and Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, San Francisco

Sean McFarland’s work synthesizes two conflicting legacies of California landscape photography. The first is that of Ansel Adams, who in the early and mid-twentieth century created an idyllic image of the region with his ubiquitous pictures of seemingly pristine, untouched wilderness. The second is that of photographers such as Lewis Baltz, who in the 1970s called attention to the fact that most landscapes, including the iconic ones Adams captured, had been indelibly altered by people. They took as their subject not the mountains and waterfalls of Yosemite but tract home developments and suburban sprawl.

A member of the second generation of Californians who experienced the landscape primarily through the window of a car, McFarland is intimately familiar with the types of places Baltz and his peers photographed. All the outdoor spaces he encountered growing up had been altered by humans. Nothing was truly untamed, and everywhere the line between natural and artificial was blurred. So it is not surprising that, in his own work, McFarland would question whether a patch of weeds in an urban lot is any less wild than a clutch of trees on a remote slope in the Sierra Nevada, or whether Yosemite Valley is any less a construction than the manicured gardens in front of tract homes in the San Fernando Valley. Yet when he started photographing in the late 1990s, he found little appeal in the cool minimalism championed by Baltz and his cohort. He wanted an escape from suburban banality. And although Adams’s bombastically pretty pictures left him wanting, too, he came to share a philosophical affinity with the photographer that Baltz would have found unthinkable. Like Adams, McFarland is moved by a powerful sense of connection with the natural world—an awareness, as he puts it, “that we are living in a linked system.”1 Although he uses far subtler and more conceptual means than Adams did to express this feeling of oneness, the sentiment behind it is no less heartfelt.

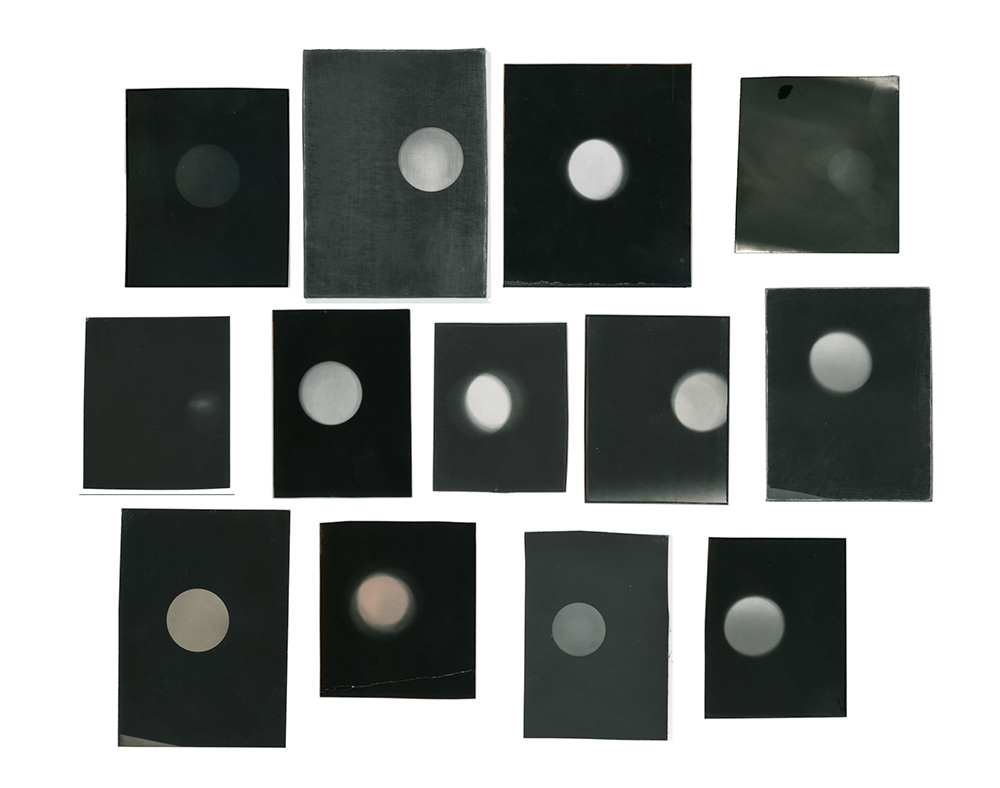

Sean McFarland, Untitled, 2016; photo: courtesy the artist and Casemore Kirkeby

Central to McFarland’s work are the tensions between the natural and the artificial and between a subject and its representation. Nowhere are these two sets of binaries more entangled than in Yosemite, a signature California landscape that has since the nineteenth century been shaped by human hands as well as by photography. The rock-lined trails to the waterfalls, the groomed campsites, and the prescribed outlooks for capturing the view all create a version of wilderness accessible for millions of tourists. As visitors we are often aware on some level that our experience is mediated, yet we are prone to overlook evidence of its artificiality. We know our perception of Yosemite is a fabrication, but we want it to be authentic, and we willfully suspend our disbelief. Much the same can be said of photography. We want to trust its truth value, even though we know that a picture is a representation and not a transparent window on the world. We are cognizant of how easily photographs can be manipulated, but we are constantly surprised when we are tricked by a fake.

McFarland describes photographs as “poetic, wonderful failures” that only approximate our experience of the world around us; he explores familiar landscapes such as Yosemite in order to “take photography apart” and consider how it operates, both optically and culturally. It is noisy, wet, and windy at the base of Yosemite Falls, for instance, but pictures don’t generally impart those visceral aspects of being there. McFarland attempts to capture them in his work, sometimes by using multiple exposures to convey a sense of movement or by allowing his photographs to “break,” as he terms it, into prismatic colors, suggesting the presence of energy outside the visual realm. In so doing he seeks to create not just a beautiful picture but one that taps into the sublime sense of oneness and mortality we feel in the presence of nature, while simultaneously reminding us that what we are looking at is an illusion.

Sean McFarland, Moon (collection), 2011–17; courtesy the artist and Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, San Francisco

McFarland turned his attention to waterfalls in particular only recently, making pictures that allude to the history of the medium—Eadweard Muybridge and Carleton E. Watkins photographed them extensively in the nineteenth century, as did Adams in the twentieth—as well as to the passage of time. Waterfalls function on a slow, geological register, as the force of the water that flows through them gradually transforms the shape of the surrounding rocks. But they also change quickly, running at various rates depending on the season and marking time on a cyclical, annual scale. Quintessential symbols of sublime nature, waterfalls possess both awe-inspiring beauty and the potential for mortal danger.

The first waterfall McFarland photographed was Rainbow Falls in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. It was a somewhat surreal experience: after snapping a few frames, he stopped to reload his film, and as he set up again to shoot, the water was suddenly turned off. Rainbow Falls contains all the visible elements of a natural formation, and for McFarland’s purposes it is irrelevant whether it is “real” or not. He is drawn as much to a man-made cascade as he is to Yosemite Falls, and in his work they are interchangeable. It is our collective idea of the waterfall and how photographs play on our expectations of what one looks like that is most compelling to him.

Photographs are satisfying, McFarland says, because they operate based on our knowledge of the way the world looks and because we know how to read the signs. He explores this effect in his constructed landscapes, such as one in which a sphere set on the cerulean ground of a cyanotype appears to be the moon in the sky, even though it is actually the white head of a pin on a blank sheet of paper. When details are missing, our minds fill them in, so a peaked piece of chipped glass can become a mountain, and a bottle cap can be the moon. Like his photographs that are taken from the real world, these illusionary landscapes explore how slippery the differences between the natural and the artificial and between a subject and its representation can be.