10–11 a.m.

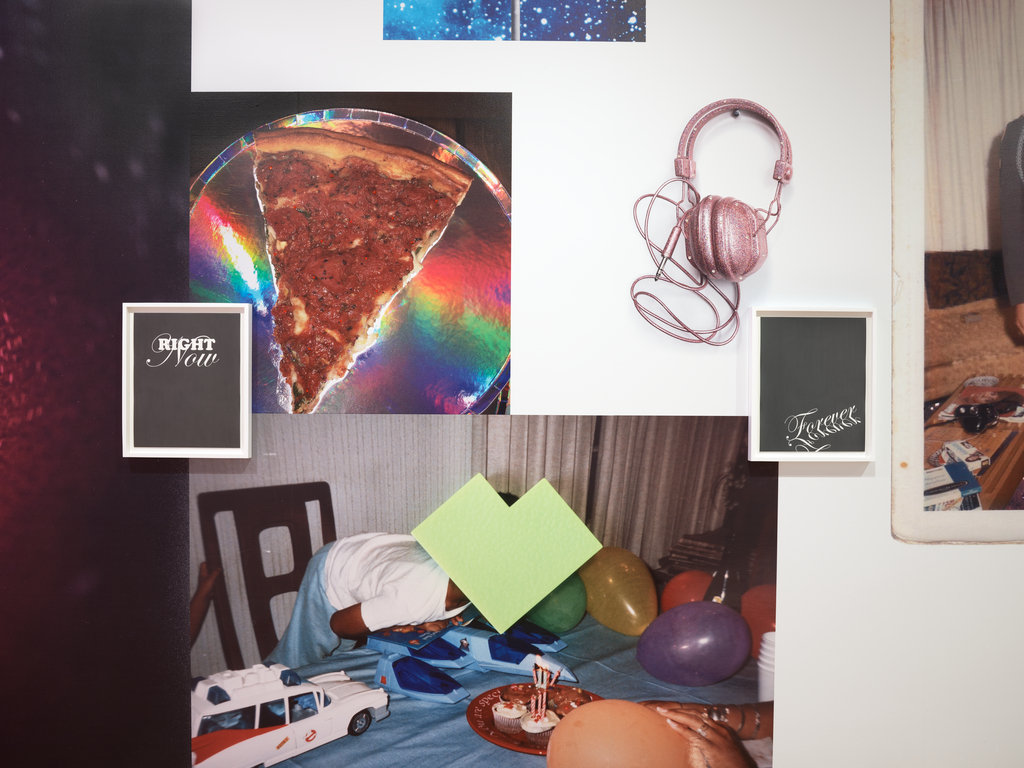

Introductions & Keynote: Sadie Barnette

SPACE/TIME: Making Art on a Rock Flying Through Space

11:10 a.m.–12:30 p.m.

Panel I: Transitory Objects

Christina Hiromi Hobbs, Stanford University, Art History

Spectral Inheritance, Transparency, and Touch: Kay Sekimachi’s Nylon Monofilament Hangings

Eric Mazariegos, Columbia University, Art History

Circuitous Visualities: Ecological, Phenomenological, and Iconographic Considerations of the Unsolid States of Tairona Art and Architecture

Keoni Correa, UC Berkeley, Rhetoric

Can the Subaltern Make Contemporary Art? Native, Folk, and Traditional Art in the Age of the Global Contemporary

Sebastián Eduardo Dávila, Leuphana University, Cultures of Critique

The Challenges of Xibalbá. Contemporary Art Practices between Chixot (Guatemala) and the Underworld of Art

12:30–1:30 p.m.

Lunch Break

1:40–2:40 p.m.

Panel II: Photography

Susanna Collinson, UC Santa Cruz, Visual Studies

Towards a Photography of Place in Aotearoa New Zealand

Joanna Szupinska, UCLA, Art History

Zofia Rydet and the “Close Other”

Sophie Lynch, University of Chicago, Cinema and Media Studies

The Blur of Twilight Labor: Sabelo Mlangeni’s Invisible Women Series

2:40–3 p.m.

Coffee Break

3–4 p.m.

Panel III: Spatial Media

Kelsey Chen, Stanford University, Modern Thought and Literature

Things Adrift: Trinh Mai’s Bone of My Bone as Feminist Refuge-Making Craft

Zina Wang, UC Berkeley, Rhetoric

Hydroelectric Atlantis: Media against Mediation

Kara Plaxa, Princeton University, History and Theory of Architecture

Othering Worlds: Leatherspace, Dyke Community, and the American Small City

4–4:50 p.m.

Keynote: Jennifer A. González

UC Santa Cruz, Professor of History of Art and Visual Culture

Silent Speech, Migratory Gesture

4:50–5 p.m.

Closing remarks