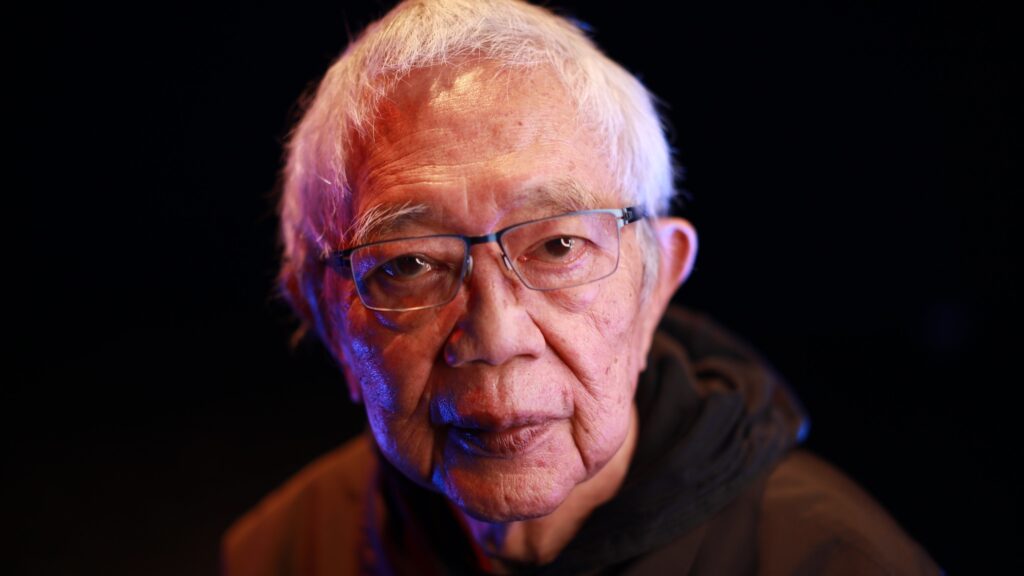

Al Wong on Twin Peaks, Art, and Meditation

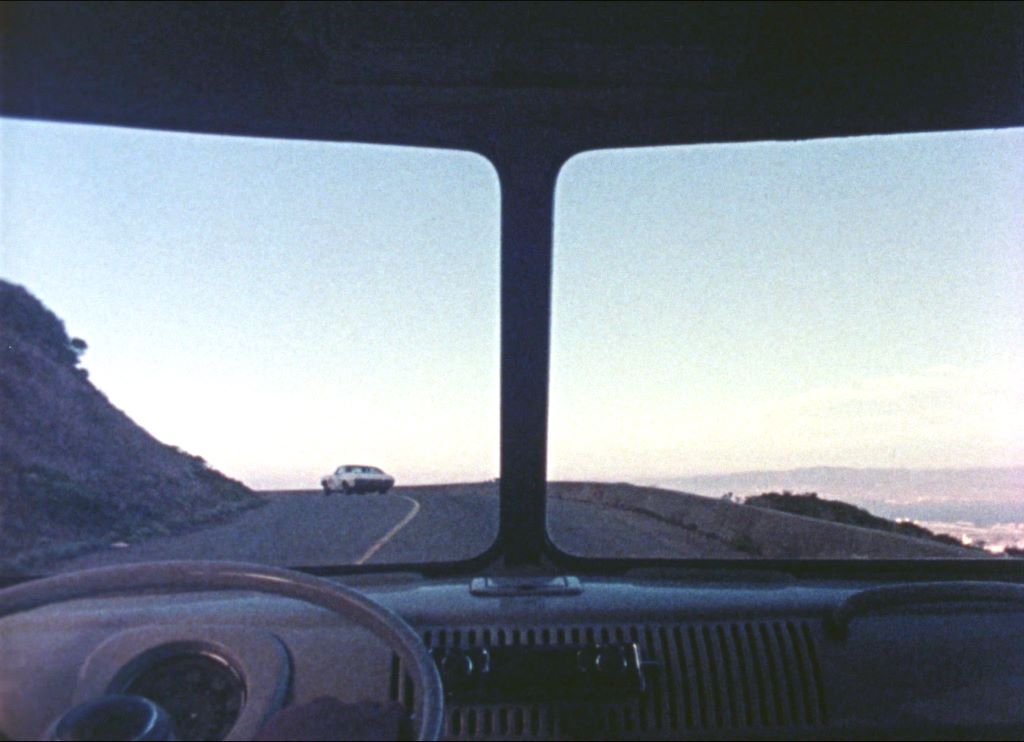

Al Wong’s film Twin Peaks (1977) traces a slow drive around the San Francisco landmark at different times of day over the course of a year. SFMOMA visitors can now experience the meditative work on a monumental screen in the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Atrium. In this interview, Wong reflects on the creation of Twin Peaks, his time at the San Francisco Art Institute, and his longstanding art and Zen practices.

How did the idea for this film come to you? And how come you chose Twin Peaks as the subject?

Al Wong: After 17 years driving a truck, the same route, I started noticing a pattern of light, color, seasons, nature, elements of change. I chose Twin Peaks because it had a road shaped like infinity. I felt like it was the form of life. The peaks were like mountains. It felt majestic.

Did you have a schedule for filming?

AW: There was no schedule really, because it was like painting. I had a pair of binoculars and from my kitchen window, I could see Twin Peaks. I could see the environment and the color, the change in weather or condition. When I needed more blue, I got in my van, I hooked up the Bolex, drove up there and filmed the infinity loop at 15 miles per hour. It was very hard because some cars didn’t want me to go that slow or fast.

Tell us more about the camera you used.

AW: I used a Bolex Rex 5. It was really close to me, that camera. We went through a lot of things. It was so expensive for me at that time, even though it was used. It was hard for me to give it away, but it was good because the digital world now is much easier. Most of my film installations are now digital.

How did you decide when to stop filming?

AW: Making any kind of art, that’s always a question. I needed all the seasons, the darks and lights, the shadow changing, the rain — all the natural elements that evolve on Twin Peaks. The last 400 feet of film is the morning light coming in. I wanted the morning light to overexpose the film, so it would be whitish or transparent. Sure enough, towards the end, the sunlight came, I saw the light, and then I ran out of film.

Tell us about splitting the view through the van’s window into two images.

AW: I put a black cloth over the van window’s divider. If I shifted the cloth more to the right, the camera would only film what’s on the left. And then I would shift the cloth to the left side to expose the window on the right. So I had two separate takes, but when I put the two films together, it looked like one Volkswagen van window. They’re shot at different times, different seasons, yet at fifteen miles an hour, they look like one road. I was interested in time and color and seasons mixed together, so I shot it that way.

I like to play. Just throw it off, have fun with it, make it a little more edgy. Make it interesting.

How have meditation and Zen Buddhism influenced your work, especially Twin Peaks?

AW: The philosophy of Zen relates to the image of Twin Peaks and the accompanying soundtrack of Baker Beach. For me, the waves were like the sound of the earth breathing. And in the zazen [seated cross-legged] position, you sit like the peaks. Still, yet extremely active. Tilting, stable and unstable, like life.

I used to sit a lot [while meditating] — I mean a lot. Sixteen hours in one day. You start to get very sensitive to your surroundings. That is, if you’re not hurting too much. Your knees, your ankles, your back. You’re thirsty, you’re hungry, you’re thinking about going home. It almost feels like it’s never going to end sometimes. It’s quite grueling.

I started meditating in 1969 and got involved with Zen Center in 1977, and then about two years after that, I started one-day sittings. You should try it. It’s fun. I can’t explain it. There’s nothing like it.

I can’t cross my legs anymore, so now I do standing meditation. I hold a ball, but energy goes through my arms.

What role did the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) play in your life and art?

AW: As a student, it opened my mind to every possible way to create. Then as a faculty member, I tried to give back what was given to me. I taught there for almost 30 years and studied for eight years. That’s a long time at that school.

I learned through experience, observing people like Jay DeFeo. One day we were driving toward the Presidio, and she says, “Oh, look at that bush in front of that house.” And I said, “Why? Why would I want to look at this bush?” And she said, “God, it’s just really beautiful the way it is.” And that struck me really hard, that I could see anything and everything in a very real way rather than the way I was taught. It was teaching without teaching.

What courses did you teach?

I was in the filmmaking department, but I was not teaching film. I was teaching that you can be open to using any medium. Well, I gave this example: I had a good friend, [artist] Terry Fox. One day he came to my house and said, “Al, you got to listen to this.” He had a tape recorder, like a Sony Walkman, and he clicked play and it was the most beautiful sound I had ever heard, I swear to god. It sounded like a thousand violins, going all together in all different directions. I said, “My god, where did you get that? Did you go to the symphony or something?” He said, “No. I was up Mount Tam.” He was doing something for SFMOMA at the time, and he was trying to record some sounds there and this Great Dane came and decided to take a big shit right in front of him. And all of a sudden, thousands of flies started devouring the shit and it made this beautiful sound as he placed the recorder closer and closer. And I said, “Oh my god, this is incredible.”

What was the San Francisco art scene like when you made Twin Peaks?

AW: I was hanging around with the conceptual artists and everybody had shows. I didn’t have so many shows. There was a show at MoMA in New York when Picasso had three floors, and I was downstairs in the basement screening Twin Peaks.

There used to be a handful of artists in the Bay Area. In North Beach, the Beatniks. Or the Dilexi Gallery on Clay Street, which was the only place that showed Jay DeFeo’s work. And then Paule [Anglim] came to the scene and opened her first gallery next to [famed lawyer] Melvin Belli’s office on Montgomery Street. Moscone Center was being dug up, and we were jumping into the construction site and making art.

Twin Peaks is now shown as a digital installation on a big screen, not on film and not in a theater. Do you embrace this new format?

AW: I’m all for it. It is making the work over again, giving it a new possibility. The theatrical screening, with all the chairs — that’s one way to show the work, but there are endless ways. I see a correlation going on between the horizontal movement of the Twin Peaks infinity loop and the vertical movement of the public going up and down the stairs in the atrium.

I’m open for anything. Project it at the sky!

Do you still go up to Twin Peaks?

AW: I went a couple years ago. My wife and I like to eat in the car. We go places and bring our lunch and look through the windshield and eat. So we went up there and ate. But the route has changed — you can’t drive in an infinity form anymore.

Do you still make art?

AW: Yes. I wake up at 4 a.m. From 5:30 to 7:30 a.m., I do Tai Chi. From 4 to 5 p.m., Tai Chi. From 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., I work in my studio. My work takes a long time, because I’m trying to find something that I haven’t found before.

Do you primarily work in film?

AW: If I chose one medium for the rest of my life, I’d be cutting myself short. It’s like if we wanted to go to New York from here; we can walk, drive, take a plane, swim across the Panama Canal, and so on. There are many ways to do it, but the experience would be very different. So, what is the idea that wants to come out? I don’t have much control over it. I’m sure you’ve probably heard this from many artists — they don’t know why, but their arms move automatically. They know where they need to go and what they need to do and they choose whatever medium.

“Everything is interconnected. We all know that. But how can I do that in art?”

Are you seeking something specific in your art?

AW: I’ve been thinking about this for a long time. As a person that’s called an artist, what is this activity and what am I making this for? Why am I here every day, sitting, drawing, and writing? Trying to find, to sound corny, the truth. And I don’t know what that is. And time is really precious now.

Everything is interconnected. We all know that. But how can I do that in art? Zen says to get rid of “monkey’s mind” — thoughts like, “Oh, I got a bill to pay. I got to meet so-and-so. I got a job to do.” What’s really important? Your life. Everything we experience, it’s impermanent. We should appreciate moments and people we’re with, because we’re all going to go. So going back to making the work, I should make it better, try my best.

With film, the work has to relate to the space. We’re here; very live, present, primary. There’s no space to allow us to break the present tense. We’re talking. This is it. If I can make art that considers that, then people can experience that or not — it’s their choice, to pay attention. It’s a subtle thing, and I feel when things are subtle, sometimes they’re really true.

Al Wong: Twin Peaks is on view on Floor 1.

Meaningful support for this presentation of Al Wong’s Twin Peaks is provided by the Joan Dea and Lionel Conacher Media Arts Exhibitions Endowed Fund and the Westridge Foundation.

Additional support is provided by Glen and Sakie Fukushima.