“There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious — makes you so sick at heart — that you can’t take part. You can’t even passively take part. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.”

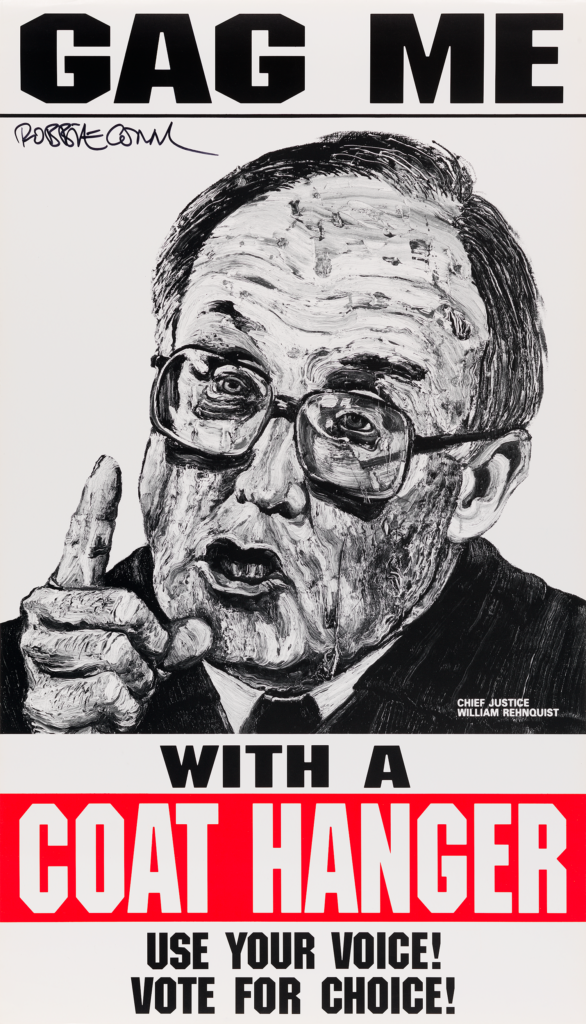

Robbie Conal, Gag Me with a Coat Hanger poster, 1991; collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund purchase

The art of the political poster is enduring, its origins cloudy, but from its beginning it has meant to inform, to stir an emotional reaction, to call attention to the potential for catastrophe, to elicit empathy and even fear. But at its heart, the political poster has sought to empower and give voice to the marginalized. Today’s political posters can be crass, colorful, and laden with pop culture references, but they also echo the cries of protesters from the 1960s through the 1980s, showing us that the issues of our times aren’t easily resolved and that history has a tendency to repeat itself.

I turned 18 the day after the 2016 election — how ironic, that I could finally exercise my right to vote the day after what could be the most divisive and polarizing presidential election in American history. It was two in the morning when I decided to flick off the light, crawl under the covers, and let darkness swallow the room. My roommate was home in New Jersey, having voted there, and I might have felt lonely had my dorm not been on Washington Square Park in New York City. Normally, impatient honking and blaring music would sound into the early hours of the morning, accompanied by the cacophony that is Manhattan’s perpetual state of construction and road work. That night, I fell asleep to the sound of a disquiet rage that surged to rebellion: the streets flooded with angry, resilient people marching from Washington Square to Trump Tower on 56th Street (a staggering 48 blocks); similar marches would occur for weeks after the election. Manhattan’s streets and avenues became battlefields upon which dissidents marched — they also became bridges to unite strangers who would not give up without a fight, and galleries for the wittiest and most poignant of protest art.

In the weeks following the election, people (and canines) flooded streets all over the world. At the Women’s March and the March for Science in Washington, D.C., and at countless other gatherings around the world, citizens marched, armored with anger, a wry sense of humor, and posters: “Sex offenders can’t live in government housing”; “Girls just wanna have FUN-damental rights”; “I’m not Sith, I’m Alt-Jedi”; “I’d even prefer Joffrey”; “I’m not a mad scientist, I’m absolutely furious”; and, a personal favorite, “I’m SAD: Samoyed Against Donald.”

i love doggo’s of #womensmarch pic.twitter.com/7xiccim3F6

— spookberry ? (@mailboxoxx) January 22, 2017

SFMOMA’s exhibition Get with the Action: Political Posters 1960s to Now strikes a resonant chord. The exhibition’s cultural and political relevance gives SFMOMA the opportunity to showcase its strong and ever-growing collection of graphic design works, but, more than that, it reminds us that the fears and losses with which we now grapple are not new, and that we have the power to endure and resist the struggles we encounter.

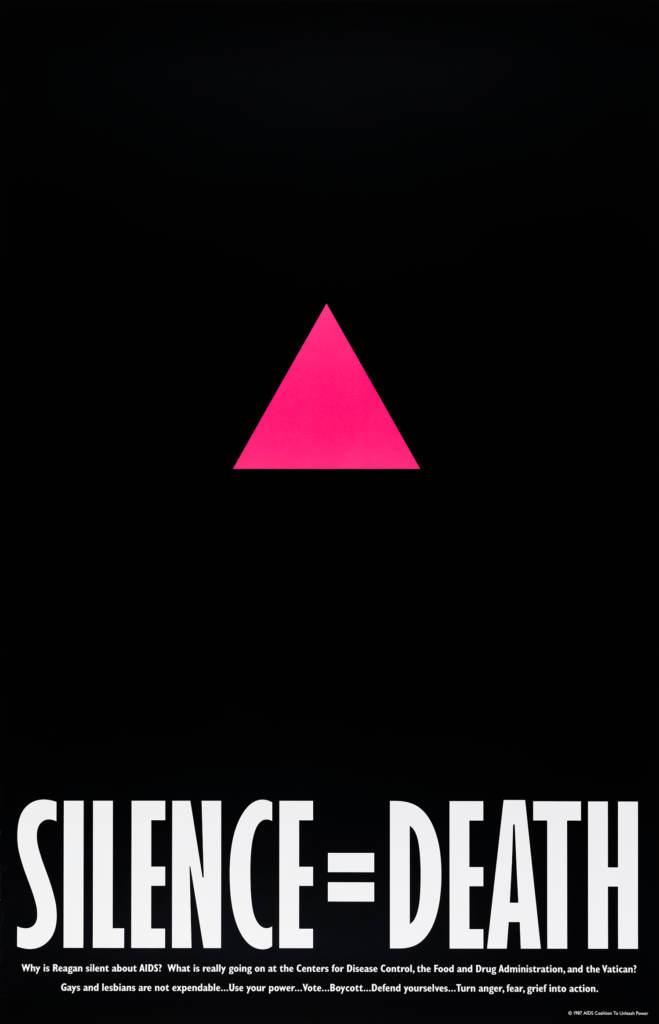

Silence = Death Project, Silence = Death, 1986; courtesy of the AIC Foundation Inc.

The exhibition features the familiar faces of Barack Obama, Michael Brown, and Angela Davis, as well as Avram Finkelstein and the Silence = Death Project’s iconic Silence = Death poster, among others. In an interview with Slate, Finkelstein said, “I refuse to do work that’s only seen within a gallery or museum context, because I feel it shuts out every person who is not extremely well-educated about art. And I know tons of people who are incredibly well-educated about everything, but they still walk into a museum and have no idea what they’re looking at.” But the political poster is an accessible art form made for and by the people, one that doesn’t require an art-based education to garner engagement and understanding. It is not merely a means of expression, but a channel, a release that is available to comfort or to galvanize.

However, Finkelstein’s latter point is striking: how do you create an inspiring exhibition for people who “have no idea what they’re looking at?” Does a political poster lose its poignancy with an audience that may be unfamiliar with the social or political movement for which it raises awareness? How does the exhibition make up for what is lost from some viewers being unfamiliar with the political climate surrounding the creation of more ambiguous posters, if at all? According to Joseph Becker, SFMOMA’s associate curator of architecture and design, “The role of the political poster is to inform a wide audience about a pressing issue. They are made to galvanize an underlying and perhaps latent desire to act on the opportunities within a democracy and incite change where change is needed.” He continues, “The political poster is not an art form that is comfortable with ambiguity — it is a direct call to action, or at least a call to attention, of something specific and of its time. The poignancy of the work is almost explicitly in informing the uninformed, and, by extension, in rallying the informed toward a cause.”

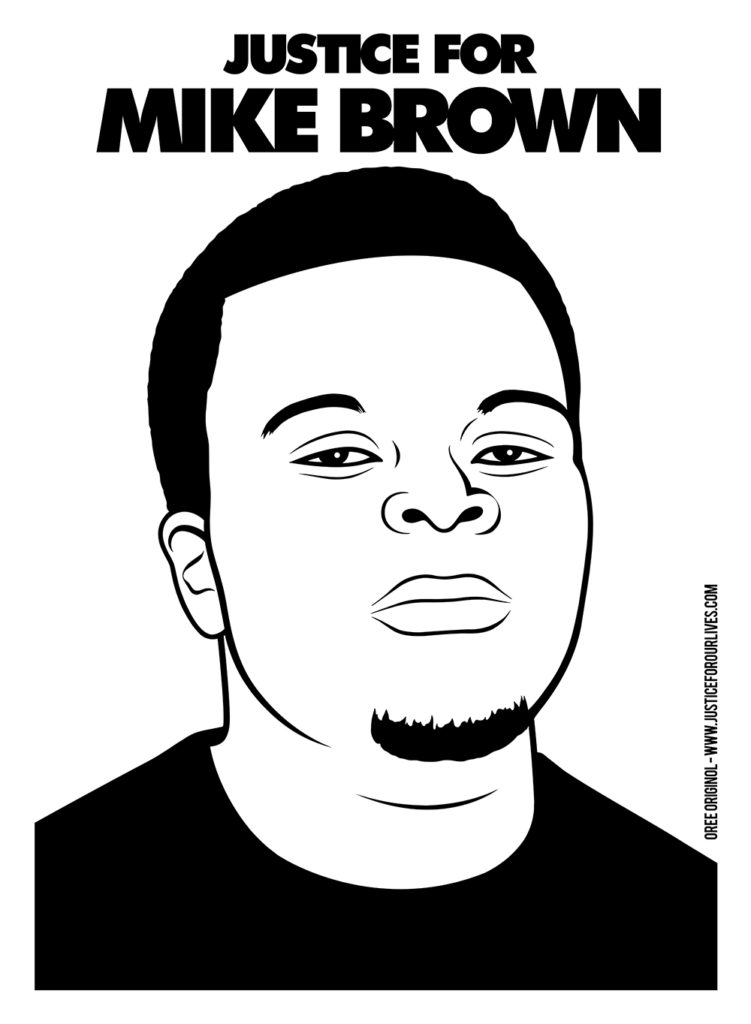

The posters in the exhibition, and their messages, transcend the limits of time. Their power lies, in part, in the call to attention that they elicit. For example, Michael Brown’s face in Oree Originol’s “Justice for Mike Brown” poster from 2014 recalls the stolen lives of African Americans from centuries ago to today. The image of a raised fist, a universal symbol of defiance, conjures both the memory and the immediacy of the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Panthers, and Black Lives Matter. Wes Wilson’s poster of a swastika superimposed on the American flag with the words, “Are We Next?” was created in response to American atrocities in the Vietnam War, but also offers a chilling prophecy of what our nation could become under the current administration.

Oree Originol, Justice for Mike Brown poster, 2014; promised gift of Jim Chanin; photo: courtesy the artist

When faced with troubling realities — fresh affronts to human rights, police brutality, the rejection of scientific evidence supporting climate change — it is easy and normal to be uncertain, angry, and scared. But from any kind of turmoil comes hope, and from hope grows resistance.

Right now, the present and future hang in a precarious balance. Human beings, with families and hopes and dreams, seek asylum in our nation only to be turned away out of an Islamaphobic and xenophobic fear of terrorists. Men, women, and nonbinary individuals who embrace their identities and seek to serve their country are rejected because of who they are. Lawmakers seek to strip women of their agency and stake a claim on their bodies. State legislatures seek to enshrine discrimination based on whom people love, of all things, in the name of religious freedom. Affordable healthcare gradually becomes more and more inaccessible to the millions of Americans who desperately need it. The chasm between the wealthy and poor only grows larger.

What do the American people lose next? Many harbor fear and anger, and for good reason. But we have not been broken before, and we will not break now. So we take our fear and anger and channel them elsewhere: we hope, love, take a stand. We make art and beckon others to join us, because that is how we resist. The political posters hanging in SFMOMA’s galleries are more than works of art; they are catalysts for change. They are reminders of who we can be, of who we are, and when we stand up and fight.

Get with the Action: Political Posters from the 1960s to Now is on view through spring 2018 on Floor 3 .