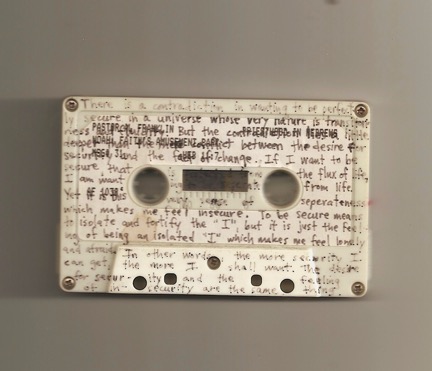

I don’t know many artists whose works are completely removed from their life and experience. Art and life are so intrinsically linked that we artists even have a hard time deciphering the distinction. I mean, really—what is the difference? It’s a fine line, blurry at best. Art, like life, is full of contradiction. Paradox. Seemingly real and tangible people, places, and things can be merely an illusionary experience. Mirages, imitations, and all kinds of misleading appearances set out to seduce and potentially shock our delicate and subjective state. Our engagement with and perception of the mundane provides fertile territory into unraveling and revealing this ambiguously complex and at times precarious region.

Enter Vija.

My kinship with her practice began approximately two decades ago, when I was a painting student at the San Francisco Art Institute. Someone back then must have told me about her work as I was diligently and somewhat obsessively honing my representational skills. “Look at Celmins’s early paintings of studio objects,” they said. At the time the advice made sense. The link was obvious: I was making paintings of utilitarian objects found in my day-to-day experience too. What struck a chord was not only the similarity in subject matter, but the parallel content. Painting the often-overlooked is a tactic—one where the unexceptional or banal takes center stage, is well lit, and given a mic. In other words, this maneuver flips the script on our knee-jerk art-historical expectations and the pecking order associated with painterly representation—aka the hierarchy of genres. The still-life tradition is known to date back thousands of years, at least to the Egyptians, although a case can be made for a link to cave paintings as well. Either way, the history is saturated with meaning and is extraordinarily diverse in culture. Vija does paint a few food items, such as fish and meat, that align her with a more commonly centered and known approach. However, I am most curious about the attention she paid to her studio appliances and how this small distinction is an important plot twist.

Imagery based on one’s daily routine through the objects one touches and uses is rife with embedded cultural significance and meaning. Whether we like it or not, identity is wrapped up in the things we utilize. Technology and the production of said items also and specifically chronicle what evolutionary point in time we humans are in. What we have access to and how we engage objects oftentimes imparts a complicated story of our values and aesthetics, both personally and collectively.

Of course, we can all tip our hats to historical godfathers Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, among many others, who rebelliously ruffled quite a few feathers back in the day. Both created work that crossed boundaries between the everyday and the high-and-mighty arena of fine art. Specifically, Duchamp and Warhol introduced mass-produced objects and imagery that already existed in real life, which challenged myths of authenticity and magic associated with the hand of the “art genius”—as did photography. Redefining accepted aesthetics is no joke, and these two blasted rigid definitions of what art is, thereby forever altering the “natural” order.

Many an alternative and differing viewpoint along “the” art-historical timeline has shifted our perspective and perception of what is important and meaningful. And what is valued. Revolutionary, indeed. In Vija’s case, the act of re-creating and re-presenting the ordinary and “low” subject of the readymade object is empowering—and needless to say, transformational—in itself. Throw in the art-historical baggage that the medium of oil paint carries with it, and we have a subversive and political act. I am rather certain that being overtly political was not Vija’s intent, as she goes to great lengths to refer to these works as her “dumb” paintings, but I couldn’t disagree with this characterization more. I find these earlier works saturated with relevant content. Don’t be fooled: simplicity is complicated.

In Vija’s depictions of studio appliances, the commonplace is given agency and power and is exalted from its minor existence, simply by having its portrait painted in oil. In its new buttery skin, the industrially produced and utilitarian becomes exceptional, elevated to new heights of prestige and cultural value. That is the performance and power of oil paint and painting. Switching, blending, hybridizing classical “fine” art definitions with contemporary categories such as the archaic separation of high and low imagery (and material) democratizes the playing field. Democratization makes way for another story to be told.

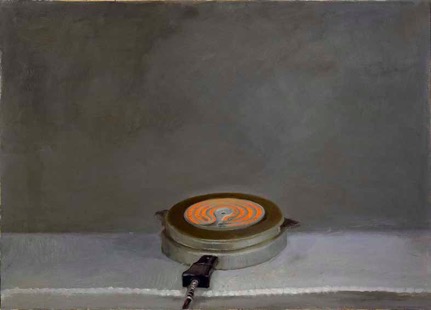

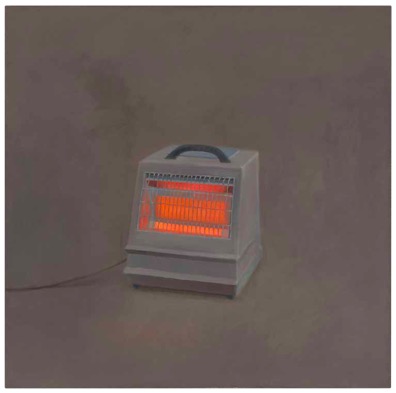

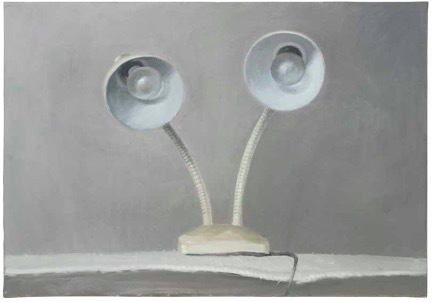

Looking closely at the four paintings of appliances arranged in the first main room of Vija’s recent retrospective at SFMOMA—Heater, Hot Plate, Fan, and Lamp #1 (all 1964)—I was struck by the sheer usefulness and flexibility of each of the items depicted. Made to be functional and nomadic in the built world, each one is compact, lightweight, adaptive to most sites with electricity, and rather easily transported. Small electric appliances perform the same function as their larger, costlier, more stable, and more decorative counterparts. For instance, a space heater is used to stay warm and can serve in place of a furnace. A hot plate is used to cook food or heat water and replaces the need for a stove. A fan circulates air in the absence of air-conditioning. A lamp gives us the ability to see in the dark without built-in lighting. Permanent home versions exist, and then there are the portable, less expensive models that bring the comfort, function, and convenience found in a secure domestic setting to a wide variety of transitional locations. Critical to note is that these items are substitutes for the “real” thing and are traditionally associated with labor, workers, and a postindustrial society and aesthetic. Stripped of frills, they support productivity, embody notions of survival, and act as signifiers of working folk and a laboring class. Vija’s painterly recontextualization lends visibility to the working class through objects associated with unseen or devalued labor. (Yes, artistic production included; artists are laborers, too.) Through the act of representation, Vija’s paintings of objects become surrogates for experience.

Formally, these paintings operate in a particular tension. Situated in the middle of the canvas, each appliance takes an attitudinal and isolated stance within the pictorial field. Transfixed, our eyes lock in an uncomfortable and static stare-down, only briefly to caress small insinuations of electrical cords. Drab and dreary, these depictions are void of extraneous materials such as bright colors, ornamental motifs, or even labels that would articulate a company name, or location. The lighting does not indicate a particular time of day. The heater and fan appear within gray, groundless voids. The lamp and the hot plate are positioned in equally nondescript domains. In every painting, items are life-size and reside within a shallow depth of field that claustrophobically leads to nowhere. Muted and dismal, the color palette is reminiscent of these objects’ steely manufacturing birthplaces, except the heater emanates a hazardous orange fever from its belly and the hot plate coils echo the cylindrical vortex of a circular shooting target and demand attention. All the while the lamp, with its E.T.–like anatomy, glares. The fan merely sits and watches. As we search for navigational clues, a sense of disorientation takes over, as does a keen awareness that danger might lurk. These paintings do not feel warm and fuzzy. Nor do they feel safe. Implications of bodily presence are noticeable, with the hot plate and space heater left running. Control buttons or knobs are entirely absent. Unable to switch off the hot plate or heater or turn on the light, one is left without agency to quell the rising tension of unpredictability. The only passage out of this unknown place is to follow the electrical cords out of the picture plane and into the lit space of the museum.

Vija’s paintings of objects offer a humble path of connection from the portrayed psychological landscape to our own. Dislocation and insecurity become common ground and experience. Themes of home, comfort, and survival are brought to the fore, as well as longings for surefootedness and stability. Broadening the lens, these paintings also provide a visual metaphor all too rife and familiar not to locate it within the context of gendered, racial, and classist leanings of the art world and the politics of San Francisco. The 1970s slogan “the personal is political” comes to mind, which links these paintings of Vija’s private experiences to that of a larger dialogue of feminist concern, and critically to the advancements and stagnations toward inclusion, diversity, and equality within the art world. I also can’t help but think of the current crisis of displacement that working folk and artistic communities have been and continue to face in San Francisco. In both situations, access to improved status and visibility are still a fight. Vija’s paintings of objects pay homage to experiences of precariousness, what it feels like to stand on ambiguous terrain, and create a visual recording of insecurity. They also offer a route to reflect on the traditionally unseen and hidden and beg the question of whose stories get told and heard.

Claiming space within the pictorial and “fine” art spheres reorients the conversation to be a collective exchange—one where everyone has a seat at the proverbial dinner table. Kudos to SFMOMA for piloting the Artist Initiative project and stepping in as a leader in supporting the multilayered and interconnected local communities of San Francisco. It has been a wonderful experience to engage with a unique group of artists, curators, conservators, and museum staff within the context of Vija’s retrospective, fostering friendships, new perspectives, and a deeper connection to her work and a deeper sense of community.

Danielle Lawrence (b. 1978, Ohio) is a San Francisco–based visual artist and educator.