Charles Gaines, Sky Box II, 2020; acrylic, digital print, aluminum, polyester film, and LED lights; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Installation view in New Work: Charles Gaines, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2021. Photo: Katherine Du Tiel

This conversation between artist Charles Gaines and curator Eungie Joo took place on March 31, 2020, in conjunction with the exhibition New Work: Charles Gaines.

Eungie Joo: Tell me about the new work that you are planning for SFMOMA—I want to know about the significance of the Dred Scott case as well as the final court decision in 1857, and why you wanted to make this the subject of the works at the museum.

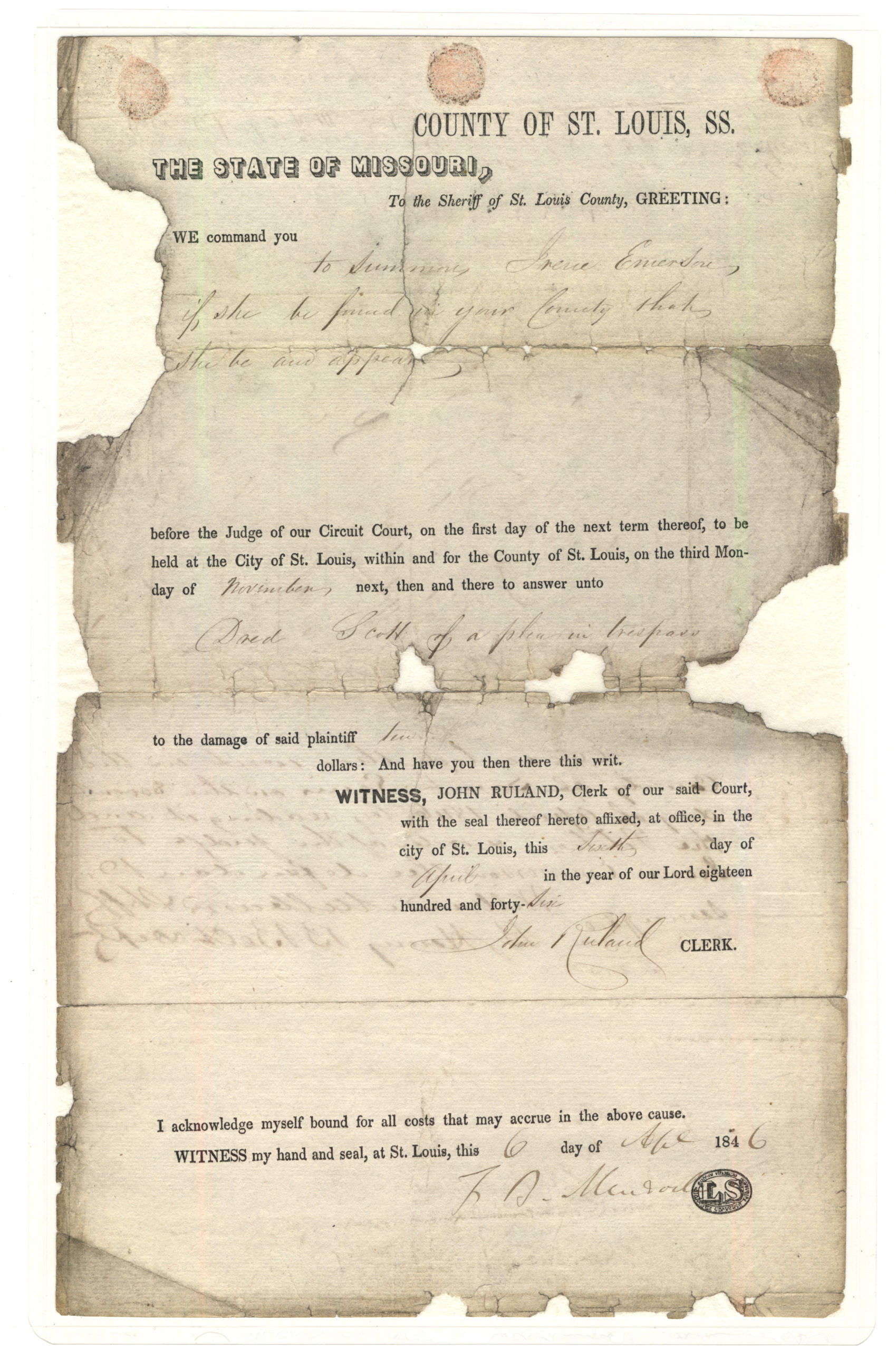

Charles Gaines: At the time that the opportunity to show at the museum came up, I had been exploring the idea of writing an opera—a Dred and Harriet Scott opera—and had already developed a bunch of research on the subject. I had been to St. Louis and gone through the files in the courthouse where the cases were held, and had a lot of scanned images of the files that the library let us take with us. I was involved in this research when the idea of the show came up, and I thought it would be an ideal time to do a new Manifestos work on Dred Scott because I had so much content. I really wanted to do a work about it that wouldn’t take three years to make but would at the same time help me with the eventual opera. In developing ideas for the exhibition, I suggested a new Sky Box work, and you thought that it was a pretty good idea and encouraged me, so I decided to do it, mainly because I do anything you tell me to do.

EJ: Oh, it’s my fault. Thank you. I’m proud.

CG: And it made sense, because I had all this written and visual material. So the idea of doing this new Sky Box piece where you walk in and see this wall of text—both scans of the actual handwritten court documents and a transcription of the rulings—really fascinated me. As you know, the piece is about the experience of a wall of text converting into a panoramic view of the night sky. It’s another work that deals with this issue of trying to advance affect based on certain linguistic, strategic movements. I was very interested in working with that idea at this scale, but again, Dred Scott is a huge subject. I think the Declaration of Independence might be as important, but that’s still up for judgment. It was a huge ruling that continues to affect our lives today in such meaningful ways. It is an event that we can point to when we talk about race and representation and all of the related issues that we often speak about. It all points to the Dred Scott decision. I was really fascinated by that—by unpacking in a work of art the complexities of this decision.

One of the things I like about the work that I’m doing around the Manifestos series is that I have the opportunity to advance certain documents from the past or even the recent present that people either don’t know about or don’t know much about. So I can resurrect important archival documents that I’ve found to have total and complete relevance to our lives today. There is this historical process in creating these works, and the investigation of these documents is a way to get into a conversation about these things. And particularly in this case, with Dred Scott, there are certain concepts and constructs that are essential to understanding this country and how it came into being.

I imagine that, among other things, it was the first decision that established that Black people weren’t human beings. Now the ruling didn’t say “Black people aren’t human beings,” but it created a legal framework to refuse the legal solution that Dred Scott sought. In other words, it came out of the framework of racism; racism became an acceptable legal argument. This was the first ruling in the history of the country—a history that is volatile in how it deals with the issue of race—that gave legal authority to racism, essentially. When you read the rulings and the majority opinion—and there are two minority opinions—when you read the arguments between those judges, all made by white people who were essentially racist, you can see how deep at its core racism is in this country. And I don’t know whether this country will ever emancipate itself from being a deeply racist environment.

EJ: The fact that Manifestos 4 uses court documents is intriguing and very different than your previous works in the series, which focus on political speech and revolutionary manifestos. What are the exact documents that you are using in Manifestos 4?

CG: In Manifestos 4 I’m using Chief Justice Roger Taney’s majority opinion and Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis’s minority opinion. What was at stake in Dred Scott’s case was that he was born into slavery and later married Harriet through the permission of his slave master. Then his slave master temporarily moved to a free state. Now what he did when he was in the free state was continue to treat Dred Scott as a slave. And it’s interesting to know that at the time the practice was that once a slave entered the territory of a free state—you could even say, entered a free territory—he was bound by the rules of that state. So as long as he was in that state, he was not enslaved. Then there’s the other thing: if the slave master tried to take him back to the slave state, it could be considered kidnapping. In my research, I found out that it was quite common that when a slave was brought to a free state, the rules of the free state persevered, and they maintained their freedom. There were court rulings consistent with this. They didn’t go to the Supreme Court, but there were local court rulings that established: “This person is free now; you can’t touch him.” And this was expected, so when Dred and Harriet began their suit, everybody expected it to be one of these hundreds of cases where he was going to be freed.

In fact, in the first trial he was freed. It’s a complicated narrative in which the “ownership” of Dred switched, and as issues of abolition and states’ rights were percolating, there was an impetus to challenge the first ruling. So the enslavers appealed to the circuit court, and the circuit court said that Dred Scott could not be free. Then some abolitionists supported an appeal to the Supreme Court. The issue was, on what basis could Dred Scott be denied the opportunity to be free once he was in a free state? He was actually suing the slave master for his freedom—for taking away the freedom that he had.

Writ of Summons to Irene Emerson, who Dred and Harriet Scott originally sued for false imprisonment. Dred Scott, Harriet Scott vs. Irene Emerson, November 1846; Case No. 1; Judicial Case Files; St. Louis Circuit Court; Missouri State Archives—St. Louis. Image courtesy the Dred Scott Case Collection, Washington University Libraries, St. Louis

EJ: I always thought that decision was based on the determination that he was enslaved and therefore could not sue because he was property.

CG: Right, but that’s not the legal basis. Having passed into a free state, Scott was free because of convention. In other words, the lower courts had ruled that slaves who moved to free states could not have their freedom taken away from them. And what’s so tricky is that the ruling was not based on whether he was property because, even as a slave, his status as property was eliminated by moving. The Supreme Court ruling was based upon the idea—upon the fact—that he could never be considered a citizen. And because he was not considered a citizen, he had no status to sue for his freedom. And the reason he was not considered a citizen is, of course, because the United States was built as a country for white people.

One of the things I didn’t know about before I did this research was that on the basis of this Supreme Court ruling, the United States is a white country—even that is false. For all white people it was a natural transition: any white person who was a citizen of a state became a citizen of the United States. You did not have to take a test; it was sort of a natural thing. To separate Black people, they had to make this special case that the Constitution was not written for Black people, just white people. And on that basis, Scott could not be a citizen.

Taney used that as the basis for his decision—that the people who wrote the Constitution were all white. But it turns out that they weren’t. It turns out that a whole bunch of Black people were involved in writing the Constitution. And this is recognized on paper, in documents, that Black people who had voting capacity at the state level participated in the writing of the Constitution. So the minority opinion asked: how can you consider this country to be made for white people when Black people were involved in creating it? The issue of the role of Black people in creating the United States, for me, is huge. And Taney knew it. Everybody knew it. But racism itself created a logic to discount that kind of legal argument. And it’s considered the worst ruling in the history of the courts. It’s embarrassingly bad. Because aside from its ethical and moral problems, it was an absolutely incompetent use of the law—totally incompetent. And it took racism to draw out that level of incompetence. So Scott lost. He had to return to the rule of his owners.

EJ: Is this the first time that you will use the perspective of legal documents? Because in other Manifestos the text is a heroic speech or an actual manifesto of purpose for a radical rethinking. And in this case, it’s a ruling, or the minority and majority opinions of the court.

CG: Yes, this is the first time. Previously I used political speech of one sort or another. It’s not that a court ruling isn’t political speech, but in those instances, I used the idea of revolutionary language to create a relation between the experience of Manifestos as a work and the idea of revolutionary politics. But text plays a much more literal role in this piece than it played in the other Manifestos works.

EJ: How did you decide to follow the style of composer Francis Poulenc and write the composition for this work for sextet?

CG: That comes from a conversation with Rodney McMillian. He asked, “Why are you using European instruments?” I tried to make the argument that I was trained in European music theory, and I know more about it than any other kind of music. And that wasn’t going anywhere. Then I made the argument that the whole point of the work is that the particular choice of instrumentation is really of no significance on the level of meaning. No matter what you use as an ensemble, it is going to produce the effect that I want—this sort of emotional component that maps a relationship with the political language. And that is the argument that I have the most conviction toward.

This is the difference between Rodney and me, generally, in terms of art. It’s crazy because he denies being an Expressionist—and he’ll get mad at me for calling him one—but he would say that the material presentation of the object has an effect on your experience of it. And I would agree—it does in terms of the experience, but there is also a level where the material effect isn’t important to you. What’s important is that it functions. For example, the diatonic scale is naturally harmonious. So you don’t have to be a composer to write melodies in diatonic scale because they are all going to be melodic. It is intended to be melodic, so the fact that it’s melodic is not important to me. The fact that it produces affect is important to me. In other words, I don’t care what the melody is; I’m only concerned about the affect it produces. Because that’s what I’m pointing to in terms of forming my critique.

So it doesn’t matter what the ensemble is. It really doesn’t. It’s going to create its own experience, but that experience has no value in relation to the critique that the work is setting up. As long as it produces this kind of thing that music does, it produces this kind of aura of affect. In the past, I’ve used the string quartet as a basic ensemble formation, but I thought that I would make a radical change in the ensemble and actually use something more modernist than the string quartet because it is purely a classical construction. I was a Poulenc fan as a young person, so I listened to Poulenc again because he did these sextets with woodwinds. They produce an entirely different musical experience than my previous compositions. Given that, the question is whether there is a conceptual change in using different instruments. I don’t think there will be a conceptual change. There will be a change in the experience because the instruments sound different. But in terms of that relationship that is produced between sound and words—between sound and sentences and how one informs and influences the other in terms of creating an emotional space for its comprehension—that is not going to change.

EJ: I am curious whether the sky you are presenting in Sky Box II is a specific location, like in your Night/Crimes works?

CG: No, it isn’t. Well, I suppose I could have focused on what was present at the moment of the rulings, but in this piece you have this panoramic view of the night sky. It’s like the way you feel if you look up at the sky—and I wouldn’t have been able to achieve that if I kept that kind of specificity.

EJ: I think that the juxtaposition of the material affect of music coming through this new form of political text in Manifestos 4 with this moment where one is immersed in language, and then language absolutely fails or disappears in Sky Box II—I think it is such an interesting idea. And I wonder if that is also connected to the expectations that you have of the sublime?

CG: I mean, you nailed it. One of the things that occurred to me in the original Sky Box I (2011) is how it really made you look at letters differently. This correlation happens between the display of the patterns of letters and the patterns of the stars, where all these metaphysical thoughts start coming into your head, driving you crazy—but it’s fine, I want that to happen. But it attributes a certain sublime comprehension of text when you think about the relationship between the formation of letters together and how letters come together to form words. It allows you to separate the letters, whereas normally, when you look at a text, you don’t do that. It interferes with reading, obviously, so you don’t do it. And that is an area where I am making the claim that the emotive component in this work is based upon provoking what we call a “sublime sense” or a “sublime sensibility” in the viewer, which is essentially a situation where the viewer confronts the limits of their imagination.

…