Jenny Gheith: You focus on the California landscape. How do you consider it in relation to the ways it has been mythologized?

Sean McFarland: Much of the landscape I experienced growing up was framed by a car window—I rarely physically accessed it. But nature has often been viewed from afar. Nineteenth-century Western paintings show landscapes no one ever saw. They’re made from sketches or collages and imagined light. These idealized portrayals have an emotional truth, but they can separate us from the environment in which we actually live.

JG: When you photograph a landscape, you typically work with the light that’s there, even if it appears artificial. Do you approach different light conditions in different ways?

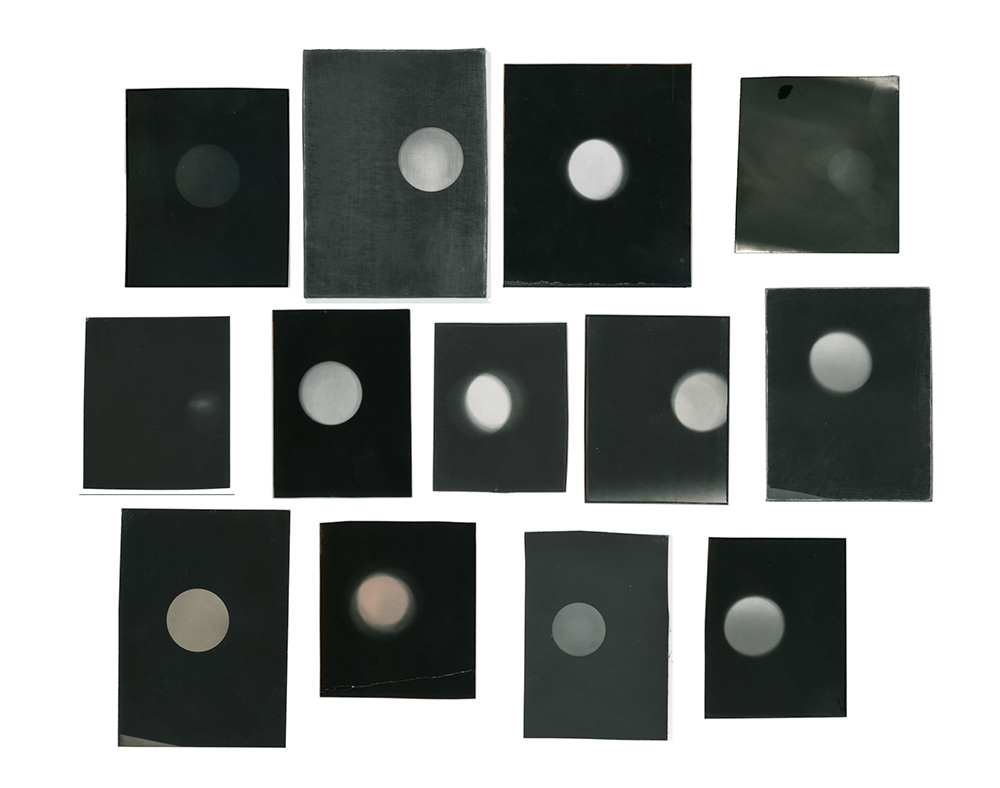

SM: We can’t control the way the sun travels around Earth. At theme parks and inside natural history museums, artificial light poses as sunlight to illuminate dioramas that pose as natural places. The same quality of light can be found in parks and wilderness—they’re also dioramas, created, through legislation, outside of theme parks or museum walls. But light doesn’t follow different laws of physics when one is portraying nature versus artifice. That’s why a picture of the moon can be made out of a nickel—light renders both as circles.

JG: Cyanotypes have a particularly interesting relationship to light. Can you explain what they are and why they appeal to you?

SM: Cyanotypes render the sky without a camera or a negative. They only need sunlight for exposure and water to process the print. I can’t think of another process that captures a subject so simply and with almost no mediation. The paper absorbs the sky and is its color.

JG: Besides making pictures, you collect images. Your archive is very present in your studio. For example, there are a number of images of waterfalls.

SM: Collecting may be a way for me to be a steward of the places and experiences in the pictures. At the same time, when you collect, the collection begins to own you. That’s why I keep returning to the same subjects. I went to Yosemite Valley again this weekend to photograph the falls. The experience is so laden with spectacle. These images don’t capture the experience of being there. They capture the experience that I want to have had and maybe the one that we all want, as opposed to the actual one where I’m in a crowd looking at a waterfall and hearing how someone wants a corn dog or their feet are tired.

JG: When the pictures are together, you lose a sense of place. How would you compare a waterfall at Golden Gate Park to one at Yosemite?

SM: Through reduction, the pictures end up the same.

JG: I think of your photographs in terms of amplification, not reduction.

SM: Through framing and layering multiple exposures, I try to turn up the experience.

By making the film hold more than one record I introduce a kind of visual spectacle, and the subject is complicated. The picture is no longer just a representation of a waterfall. Photographs aren’t good at holding noise, wind, and mist, but they can allude to those elements, while at the same time revealing the clear difference between what we experience and what pictures can record. Cropping out a path removes the park, and adding multiple exposures creates a picture about a fictional experience that is possibly closer to the actual one.

JG: Some of your projects overlap with those of other artists, such as Walter De Maria. And when you mention what an image can hold or what feeling it can impart, I can’t help but think of conversations we’ve had about Ralph Eugene Meatyard.

SM: I’ve made and photographed collages of tornadoes, avalanches, and lightning strikes to make pictures of sublime phenomena. I haven’t been to De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977); you can watch lightning strike there, but you aren’t allowed to take photographs. In 2013, when I was in the Eastern Sierra Nevada doing trail work, I made a video that captured a lightning strike and found out later that De Maria had died that afternoon. That was the first time I had been able to make a record of a lightning strike—the day of his death. There was an invisible artwork between the death of De Maria and my witnessing of the lightning strike, events that created a context suggesting a collective consciousness, an interconnectedness between people and the landscape.

JG: This sense of interconnectedness seems to have grown stronger with your Rockwell/Meatyard project.

SM: Totally. Rockwell was a ranger who lived in the Eastern Sierra Nevada, where I make the majority of my work. At an estate sale my brother purchased Rockwell’s maps, photographs, and negatives. Looking through them one day I was reminded of the last three pictures Meatyard took of himself before he died, which were self-portraits of him walking up a hill, toward a tree. Among Rockwell’s negatives were three pictures that were compositionally identical to Meatyard’s. For lack of a better word, it was a spiritual experience—I felt connected to both of them, and the context connected them to each other. I began looking at my work from when I started making pictures, Meatyard’s pictures, and Rockwell’s. I made three self-portraits similar to Meatyard’s and Rockwell’s on one roll of film in 1998 and a picture in 2012 that mirrors one of Meatyard’s photographs of Kentucky’s Red River Gorge. The name Rockwell appears in the only photo-graph I have ever seen from Meatyard’s notebook, which he called the Book of Odd Names. I’ve been using multiple exposures in an attempt to make synesthetic pictures, much like Meatyard’s intention in photographing the Red River Gorge, which he worked along with writer and farmer Wendell Berry to save from being dammed, flooded, and lost. Those were some of the first pictures in his Motion Sound series (1967–71).

JG: Were they successful?

SM: They were.

JG: It’s pretty incredible to think about the power images can have.

SM: That’s my biggest issue right now. How do I visually unpack an emotionally and spiritually complicated concept without subscribing to the formalism that often “others” the landscape? Behind you is a large picture of a mountain with rainbow colors that uses Meatyard’s techniques. When you take a photograph that’s black and white and break it into its pieces, it’s an equal representation of all the colors in the visible spectrum. It’s an attempt to depict the unseeable.

Excerpted from an interview conducted at Sean McFarland’s studio in San Francisco on February 22, 2017. Originally published in Jenny Gheith and Erin O’Toole, eds., 2017 SECA Art Award: Alicia McCarthy, Lindsey White, Liam Everett, K.r.m. Mooney, Sean McFarland (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2017).