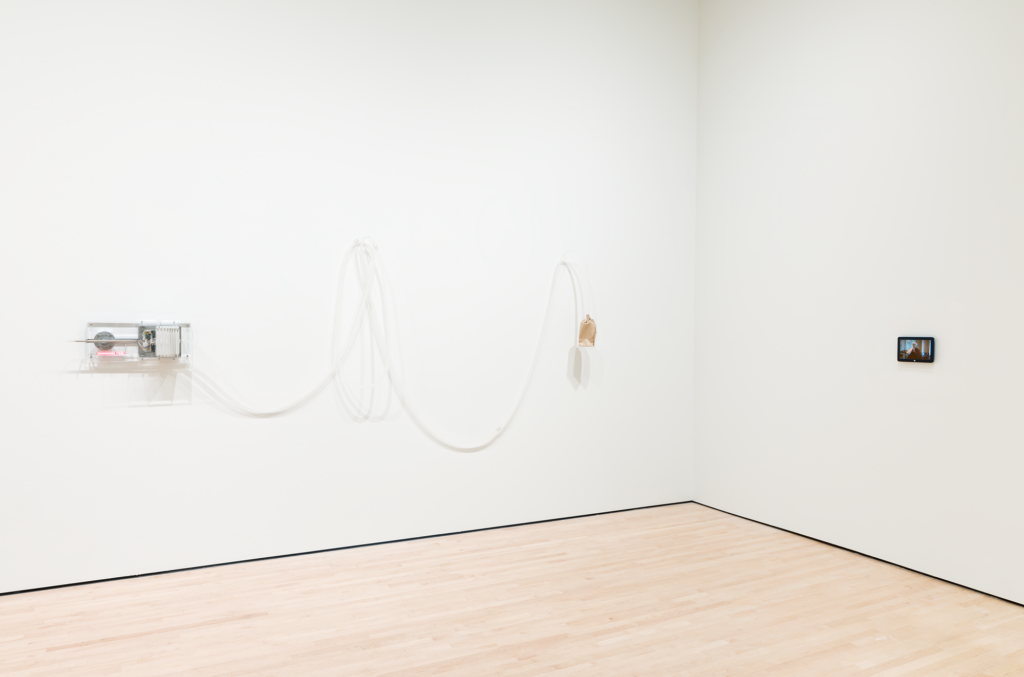

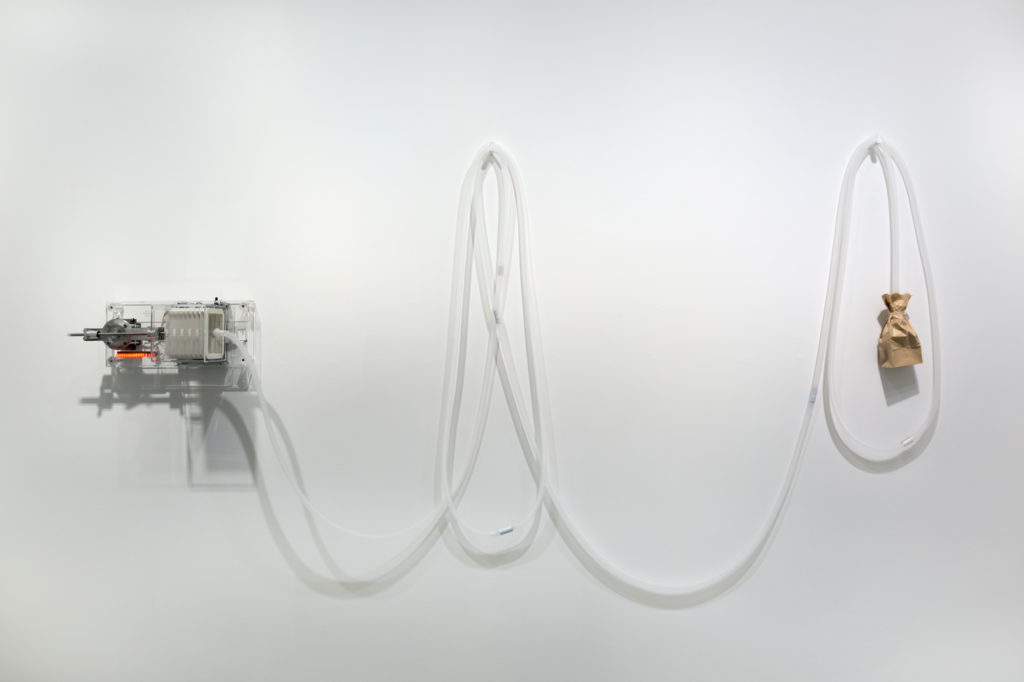

Last Breath, 2012

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s oeuvre is indebted to a tradition of creative experimentation with technologies in Latin America, such as the early use of radio by poets. He has produced a range of works that incorporate the detection and recording of the sounds and physiological functions of the human body—pulse, breath, or voice. Typically, in these works, a room is filled with collective presences. In the case of Last Breath (2012), however, the viewer experiences a biometric portrait of only one individual, here the American composer, electronic musician, and accordionist Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016), who co-founded the Tape Music Center in San Francisco in the 1960s. This kinetic sculpture consists of a small, brown paper bag with a plastic resin lining, connected by a long tube to a bellows activated by a motor, an apparatus similar to those found in artificial respirators in hospitals, encased inside a Plexiglas box. Ten thousand times a day, the paper bag inflates and deflates, simulating the normal respiratory frequency of an adult at rest. Each stroke of the machine advances a digital counter that beeps. This is, of course, exhausting in the long run, so the machine not only breathes but also audibly sighs 158 times a day. Nearby, a sixteen-second video of Oliveros breathing once into a paper bag, which Lozano-Hemmer recorded on his cell phone, plays on a small screen. By literally as well as figuratively capturing a person’s breath, the artist creates a living memorial to that ephemeral moment of breathing.

Last Breath is completely transparent; nothing is hidden in the Plexiglas container, suggesting that one can almost perceive the intangible thing that is breath, and that the artist and the collecting institution have taken every measure possible to preserve Oliveros’s breath inside the machine. The artist purposefully chose a linear mechanical motion that comes from a circular rotation, as in a locomotive, for the system activating the bellows. The tube that telescopes out, channeling the air between the respirator and the paper bag, forms parabola shapes. The machine is almost analogous to a musical instrument, producing the rhythmic, crumpling noise of the bag as it inflates and deflates, and the faint, low sound emanating from the ribbed tubing. The bellows’ movement and the airflow within the apparatus are particularly evocative of Oliveros’s lifelong work as an accordionist.

While the aesthetics of the sculpture are reminiscent of medical and technical apparatuses, the work resonates with historical examples of scientific speculation, such as that of the nineteenth-century British scientist Charles Babbage, who proposed that all the molecules of air contained within their motion the speech of every person who had been alive up to that time. From this, we could conclude that the air we breathe is not neutral but enhanced with molecules of memory. Lozano-Hemmer characterizes the subjects who agree to be part of Last Breath—an earlier version, conceived for the Havana Biennial in 2012, held the breath of the legendary Cuban singer Omara Portuondo—as open to being “romantic, in the sense of this idea of preservation of the elusive and intangible, but also [having] a sense of humor. . . . fortunately, both Omara and Pauline have that sense of humor. They understand that this is an impossible, an absurd exercise. And in that absurdity lies the strength of the project, because we all know that no matter how hermetically sealed my chambers are, eventually those molecules will disappear.”1

— Rudolf Frieling

Sphere Packing, 2013 and 2014

Apple’s ubiquitous signature white earphones form the basis of the Sphere Packing series by Mexican artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer. Each of these sonic sculptures “packs” a collection of musical compositions into one spherical representation, assembling and condensing the production of a composer in its totality. The artist uses the emerging technology of 3-D printing to cast these spheres in different materials, and adjusts the scale of each to correspond to the number of distinct compositions that constitute the composer’s oeuvre—not an easy task in itself, requiring tracking down every single recording by a single composer.

Lozano-Hemmer’s approach is tied to the way that music is consumed today—hence the iconic earphones—but it couldn’t be further removed from the ideal conditions of listening to a live performance in a concert hall. Not only do the listening devices provide an inferior sound quality and acoustic experience, but the volume is reduced to a minimum, to a faint trace that barely triggers acoustic memories. Further, even within a single sphere the distinct sonic elements are compromised by their proximity and replaced with a murmur, a sound that only dissolves into individual recognizable musical performances when the visitor comes extremely close to the object with its dozens—if not hundreds—of earphones.

The three works selected for Soundtracks are Sphere Packing: Mozart (2014; white polymer, 565 audio channels), Sphere Packing: Wagner (2013; glazed porcelain, 110 audio channels), and Sphere Packing: Cage (2014; plastic, 269 audio channels)—an abridged walk through the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries.2 The series as a whole, featuring seventeen composers, constitutes nothing less than a broad history of classical music, with surprising insights in terms of productivity, ranging from seventeen compositions (by Claudio Monteverdi) to 1,128 (by Johann Sebastian Bach). A less literal and more evocative reading is prompted when one considers the relationship between a work’s sculptural material and its musical content. Glazed black porcelain for Wagner, for example, might evoke the composer’s notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, amassing all of his lengthy compositions into a fragile but dense object.

But these analogies do not sufficiently explain the artistic gesture of embracing totality in sound. Lozano-Hemmer likes to point to two anecdotes involving seminal composers of the twentieth century. The first is John Cage reportedly stating that he would conduct Beethoven’s symphonies “‘if and only if he could conduct all simultaneously’; and the other is the practice of American composer Charles Ives listening to several sources of sound simultaneously, apparently he loved to sit by the entrance of the church so he could hear the sounds of the city while simultaneously paying attention to the concert inside.”3 What is at stake here is thus a radical interpretation of simultaneity, of being in different acoustic worlds at the same time.

The development of new audio technologies has distanced the act of listening to music from the live performance step by step, allowing it to become first a recorded and reproducible event at home or in a club via vinyl and tape, and then a mobile, personal experience with the tape-based Walkman of the 1980s. Finally, today’s mobile multifunctional devices can hold digital music files and combine the function of a music player with access to global cloud storage, making countless recordings available to the listener at any time. The Sphere Packing series thus gives form to an archive that connects this aspect of contemporary music consumption to the idea of simultaneity not as a conflict but as an essentially modern condition. An entirely new sonic experience of how Mozart, Wagner, and Cage “sound” unfolds in the softest manner. A sphere is a fitting form in that it embodies an act of physically relating to a body of work as one walks around the production of these composers. There is an evident need to get close, engaging with multiple points of access or sources of sound while recognizing that not all earphones are positioned in such a way that one can bring one’s ear close enough to listen to it all. The totality is as much real as it is ephemeral and out of reach.

— Rudolf Frieling

Notes

- Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, unpublished interview by Rudolf Frieling and Peter Samis, SFMOMA, December 19, 2013.

- For a complete list of Sphere Packing works, see “Sphere Packing,” Rafael Lozano-Hemmer website, https://www.lozano-hemmer.com/sphere_packing.php.

- Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, email to the author, April 25, 2017.

Artist Interview

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer discusses Last Breath (2012), a mechanical sculpture that captures the breath of a given person in an imperfect attempt to retain their presence even after they have passed away. The iteration of this work included in SFMOMA’s Soundtracks exhibition displays the breath of the late experimental composer Pauline Oliveros, an influential Bay Area performer and teacher.