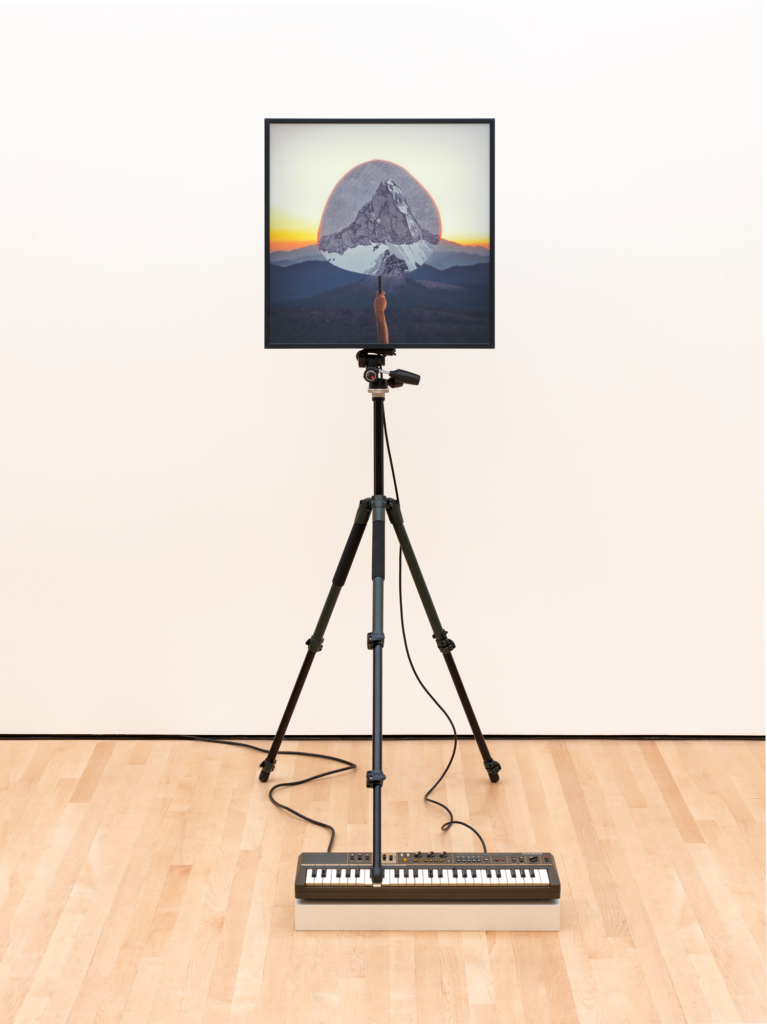

a paradox in distance, 2014

The quest to reach a mountain summit—both as a physical feat and as a metaphorical idea of triumph—has captured cultural imaginations for centuries. However, from the vantage point of a peak, one is confronted with yet another remote location, or what Richard T. Walker describes as an absence that we translate as distance. He notes, “This inability to really be ‘there’ whilst acknowledging the values that constitute being ‘there’ is a paradox that has essentially formed the foundations of what I do. The inability to acknowledge experience without reducing it to an ‘acknowledged experience.’”1

In a paradox in distance (2014), Walker visually collapses the distance between two summits in time and space. The artist’s hand is seen holding up a circular cutout of a mountain peak from a nineteenth-century engraving, placing it in front of, and in alignment with, Mount Shasta in Northern California. A tripod supports the lightbox on which this destabilized representation of the landscape appears, one leg resting on a Casiotone keyboard on the floor, on a single key, which emanates a sustained note. Walker describes the sound as “form[ing] a presence that fosters this sense of movement defining the image/object/space relationship as one that is fluid, active and endlessly relational.”2

A number of Walker’s works feature the unique profiles of various peaks as depicted in historical engravings. Others simulate them as sculpted ridgelines in neon. Walker has also created video and photographic narratives in which he appears as a solitary anonymous character, embodying and riffing on the man-contemplating-nature archetype of nineteenth-century painting.3 In live performances incorporating video projections, he has appeared as both protagonist and performer, addressing the landscape through monologue, song, and music.4 The music and rhythm are often built up by layering notes from multiple edits within a video or in combination with live or sculptural elements. Walker at times employs rocks as “performers” to depress a note on a keyboard or hit a pair of cymbals. Tripods, keyboards, and isolated images of mountains are recurrent elements in Walker’s oeuvre. These motifs are brought together in a range of media and in different combinations with other props such as instruments and tape recorders. A paradox in distance thus distills a performative gesture into a single image and continuous soundtrack.

Compelled by the vastness of American landscapes as represented in film and photography, the British artist, now based in San Francisco, first traveled through California and the Southwest in 2006 to see the regions’ striking vistas in person. He anticipated being let down but instead found inspiration. Exposing a fantasy or a preconceived understanding of an experience would become a theme in his work. By layering musical performance, spoken language, and recorded speech, Walker attempts to unite opposing attributes of experience—thoughts and emotions. The artist draws a parallel between being alone in the wilderness and being with someone you love intimately, describing both as situations that “encourage a micro and macro delineation of self that in many ways relates to the sublime.”5 The real landscape mirrors an internal landscape, serving as a meditation on human existence and consciousness.

— Tanya Zimbardo

Notes

- Emma Kemp, “A Vast Landscape Fills the Frame: An Interview with Richard T. Walker,” Trop, April 1, 2014, https://tropmag.com/2014/a-vast-landscape-fills-the-frame-an-interview-with-richard-t-walker/.

- Artist’s statement, 2014, Permanent Collection Object Files: a paradox in distance, 2015.22, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

- Caspar David Friedrich’s rückenfigur—a lone figure facing away from the viewer—was a signature of the German romantic painter’s landscapes. Walker’s uniform of a red shirt in his work is a subtle tribute to the British romantic John Constable’s characteristic use of carmine pigment. His performance-based work in nature dovetails with more contemporary approaches of direct physical engagement with the environment, reflected in the walking practices of certain British land artists since the 1960s such as Hamish Fulton and Richard Long.

- For an example of the artist’s live performance, see the video of the speed and eagerness of meaning (longer longing version) (2012), presented at SFMOMA as part of the exhibition Stage Presence: Theatricality in Art and Media in 2012, at https://www.sfmoma.org/event/richard-t-walker-the-speed-and-eagerness-of-meani/. The performance features Walker playing guitar in tandem with his two-channel video the speed and eagerness of meaning, adding another dimension to a work that explores the intersection of human consciousness and the natural world.

- “Interview with Richard T. Walker,” Aesthetica, March 3, 2013, https://www.aestheticamagazine.com/interview-with-richard-t-walker/.

Artist Interview

Bay-Area based British artist Richard T. Walker discusses his conceptual sculpture a paradox in distance (2014), included in SFMOMA’s exhibition Soundtracks. In this sound-based work, he meditates on the allure of distance in both landscapes and romantic relationships, and reflects on the ability for music to fill the gaps between meaning and expression that words often fail to bridge.