“Is it four stars? Worth a detour?”

“Is it four stars? Worth a detour?” That was the catchphrase of one of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s most generous and instrumental trustees, Phyllis C. Wattis. Inspired by the star ratings awarded to destinations in the Michelin Guide, she found the question could apply just as well to journeys in art.

Robert Rauschenberg in the SFMOMA galleries with Phyllis Wattis during the exhibition Robert Rauschenberg, May 5–September 7, 1999; photo: © 1999 Sidney B. Felsen

Robert Rauschenberg: Erasing the Rules, on view through March 25, 2018, is dedicated to Phyllis Wattis. This major retrospective of more than 150 works is arranged chronologically, highlighting sculptures, paintings, Combines (sculpture/painting hybrids), photographs, and works on paper made throughout the artist’s career, from the 1940s to 2007. The show explores Rauschenberg’s collaborative relationships, constant experimentation with materials and processes, and radical rethinking of what art could be.

Wattis’s impact on SFMOMA can be seen throughout the retrospective, from the first to the last gallery. Her generosity made possible the acquisition of the core of SFMOMA’s Rauschenberg holdings, and she was instrumental in making the museum’s collection one of the best and most significant in the world.

When SFMOMA’s Mario Botta–designed building opened in 1995, some critics questioned whether the art lived up to the architecture. Wattis set out to rectify the situation, telling Gary Garrels, Elise S. Haas Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture, to make a list of 20 artists he thought were important to have in the collection.

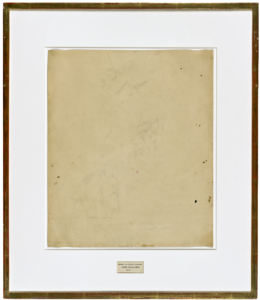

One of the artists on that wish list was Rauschenberg. Specifically, Garrels sought a 1960s silkscreen painting to complement the museum’s early Rauschenberg Combine Collection (1954/1955), given by Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson in 1972. However, before they could acquire one, David A. Ross, SFMOMA’s director at the time, received a call from Pace Gallery in New York: Rauschenberg was willing to sell his iconic Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953). Garrels says, “I immediately went over to see Phyllis. Her eyes lit up like saucers, and she said, ‘That would be worth a detour.’ Then she said, ‘What else would he be willing to sell?’”

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953; collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg created Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), for which he painstakingly erased Willem de Kooning’s work, as an act of both rebellion and homage. Though created in 1953 with permission (and a drawing) from de Kooning, the piece was not officially displayed as an artwork until 1955, when Jasper Johns suggested Rauschenberg frame it for a group show at the Elinor Poindexter Gallery. By the time it was acquired by SFMOMA, the work was considered a watershed of twentieth-century art and had been hotly pursued by a number of museums and collectors. Sarah Roberts, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Painting and Sculpture, says, “I think it was a turning point for him to let it go into a public collection, and opening that door allowed him to start thinking about placing other important pieces that he had held onto.”

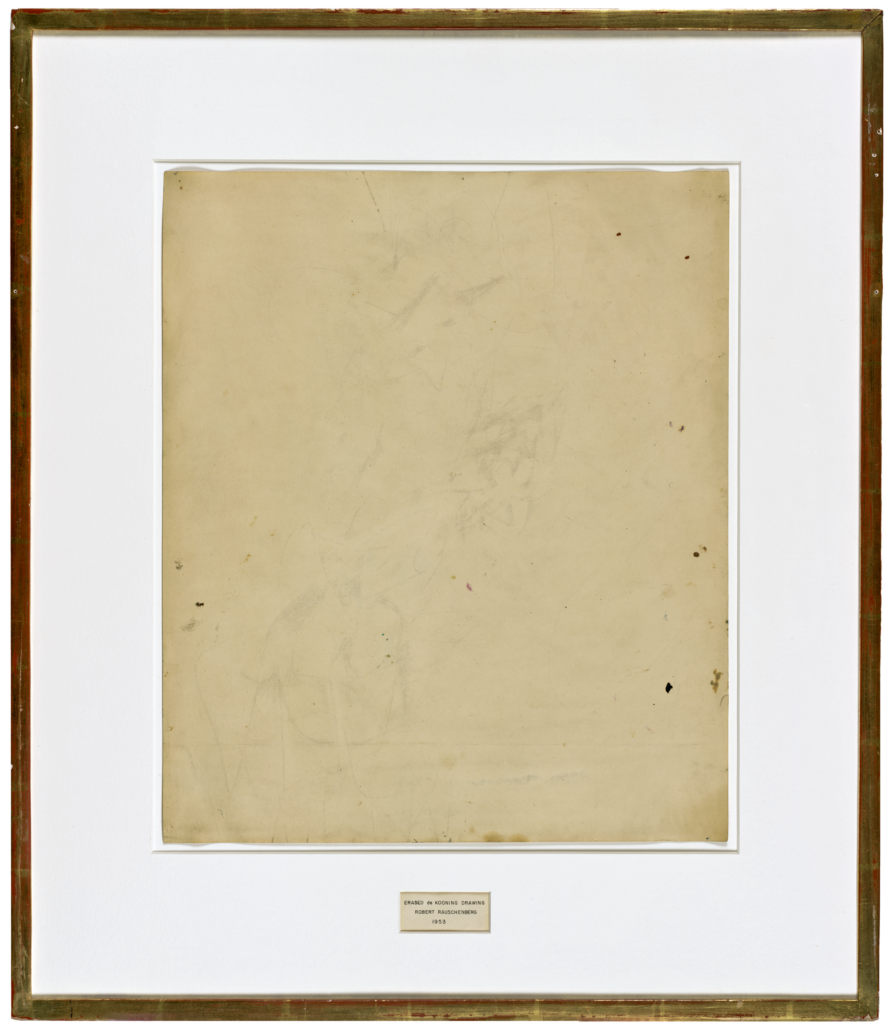

The museum acquired 14 Rauschenberg works in 1998, funded by Wattis, with additional support from two other trustees. At the time, this astonishing acquisition represented one of the most significant commitments any museum had ever made to a living American artist. Along with Erased de Kooning Drawing, the group included Automobile Tire Print (1953), White Painting [three panel] (1951), and Mother of God (ca. 1950), one of the artist’s earliest surviving paintings. When the acquisitions were announced, Rauschenberg wrote, “I feel like the museum has taken on another partner.”

Robert Rauschenberg, Automobile Tire Print, 1953 (detail); collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY; photo: Ben Blackwell

In celebration of the works coming into the collection, Wattis hosted a luncheon at her house with Rauschenberg in attendance, and the pair instantly bonded. “They sat next to each other at lunch and were just immediate friends. Their spirits were so compatible,” says Garrels. Afterward, Rauschenberg sent Wattis a package (marked “To Phyllis” with a big heart) containing a portfolio of Shirtboards — a set of prints based on an earlier series of collages that Rauschenberg had made in Morocco. The gift was inspired by their lunch conversation, in which they discovered they had both traveled there in 1952. After receiving the package, Wattis playfully said to Garrels, “I think he’s sweet on me.”

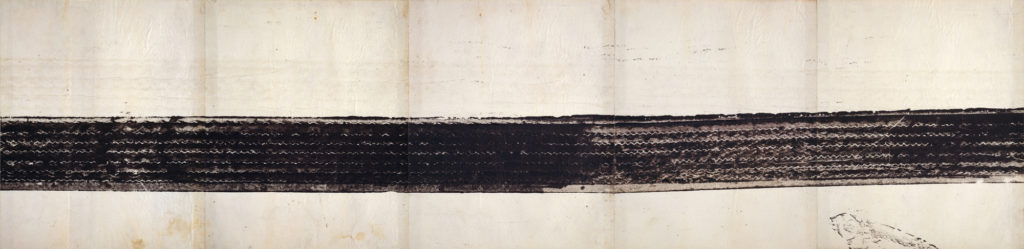

The following year, Rauschenberg gave Hiccups (1978) to the museum in Wattis’s honor. The work, which Wattis called “unpredictably original,” consists of 97 handmade sheets of paper layered with solvent transfer images and collaged bits of cloth and ribbon, and connected by zippers. Roberts says, “Each one of these panels is its own little Rauschenberg, and the idea is that they can be rearranged and zipped together in any order that you choose.” In the exhibition, it is displayed as one continuous frieze around a single gallery.

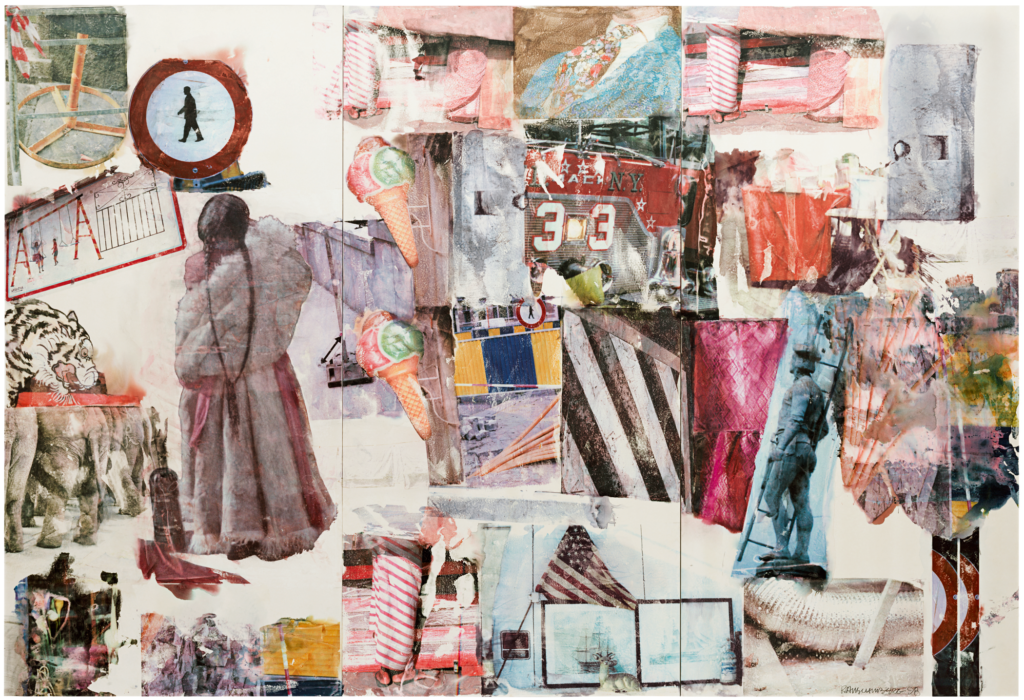

Along with the 14 works in the initial acquisition, Wattis fell in love with a very late Rauschenberg called Port of Entry [Anagram (A Pun)] (1998), which the museum also acquired in 1999. The work was produced using a digital color-transfer process. Always on the forefront of technology, Rauschenberg’s studio had acquired an Iris digital inkjet printer in 1992, which allowed Rauschenberg to print his photographs using less-toxic, water-soluble inks and dyes. Roberts explains, “That was part of what fed his imagination and kept him going—this constant invention with materials and processes.” Port of Entry repeats images and patterns, combining photographs of Americana with those from the artist’s extensive travels, and, as Anagram [A Pun] (the name of the series) suggests, creating a visual puzzle for viewers. The large, sumptuous work is on view in the last gallery of the retrospective.

Robert Rauschenberg, Port of Entry [Anagram (A Pun)], 1998; collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Wattis’s generosity and impact are still felt at the museum today. In 2013, funds from Wattis’s endowment, the Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions, were used to purchase Rauschenberg’s Rosalie/Red Cheek/ Temporary Letter/Stock (Cardboard) (1971). The same year, the museum launched the Rauschenberg Research Project, a public online resource featuring scholarly research and documentation on Rauschenberg artworks in the collection. SFMOMA now holds more than 85 Rauschenberg works, dating from 1949 to 1998, and has become a leading authority on the artist. Wattis’s legacy continues with this retrospective. As she would say, it’s worth a detour.

Robert Rauschenberg: Erasing the Rules will be on view through March 25, 2018.