What is the relationship between seeing and believing? This age-old question took on new urgency in the mid-19th century as breakthroughs in photography made visible what the naked eye could never before see, from microscopic crystals of snowflakes to the interior of the body and small increments in a horse’s stride. Some even believed the novel technology had the power to capture supernatural phenomena.

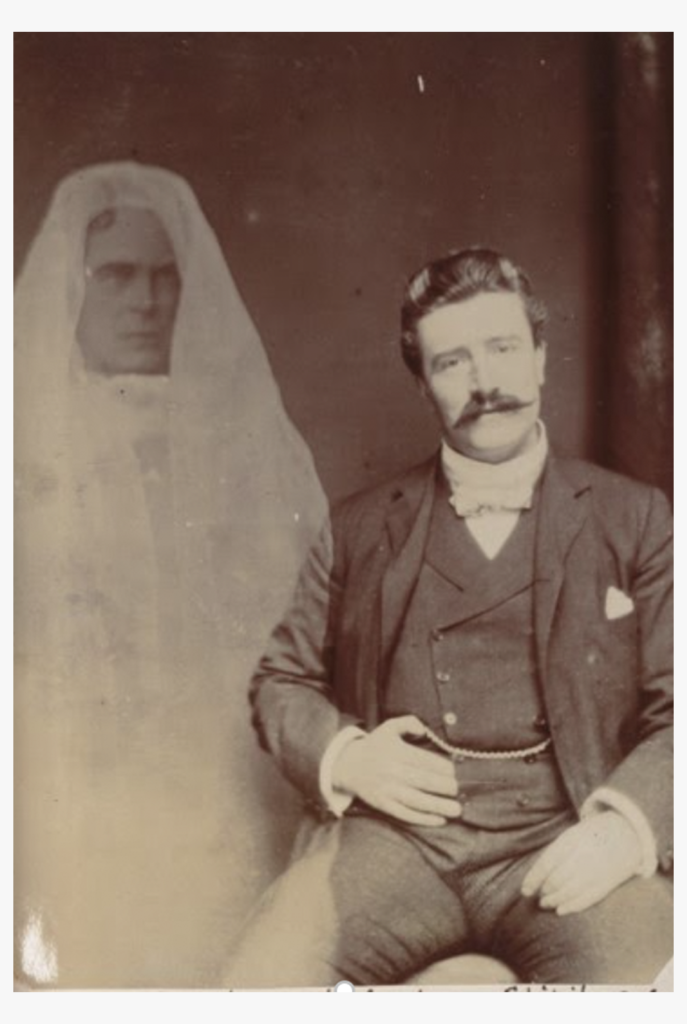

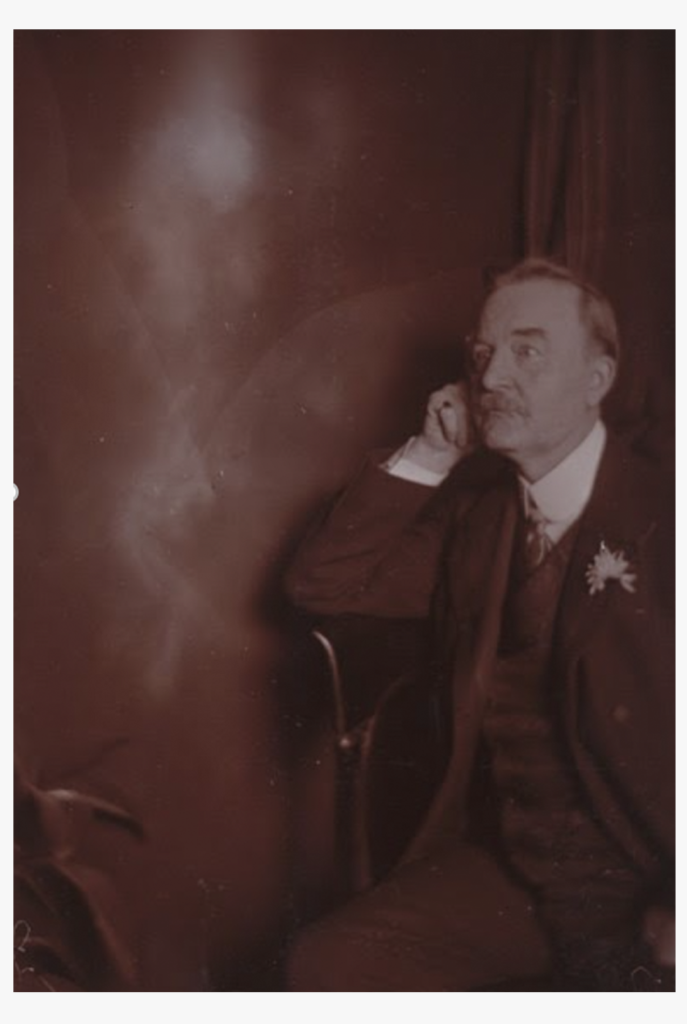

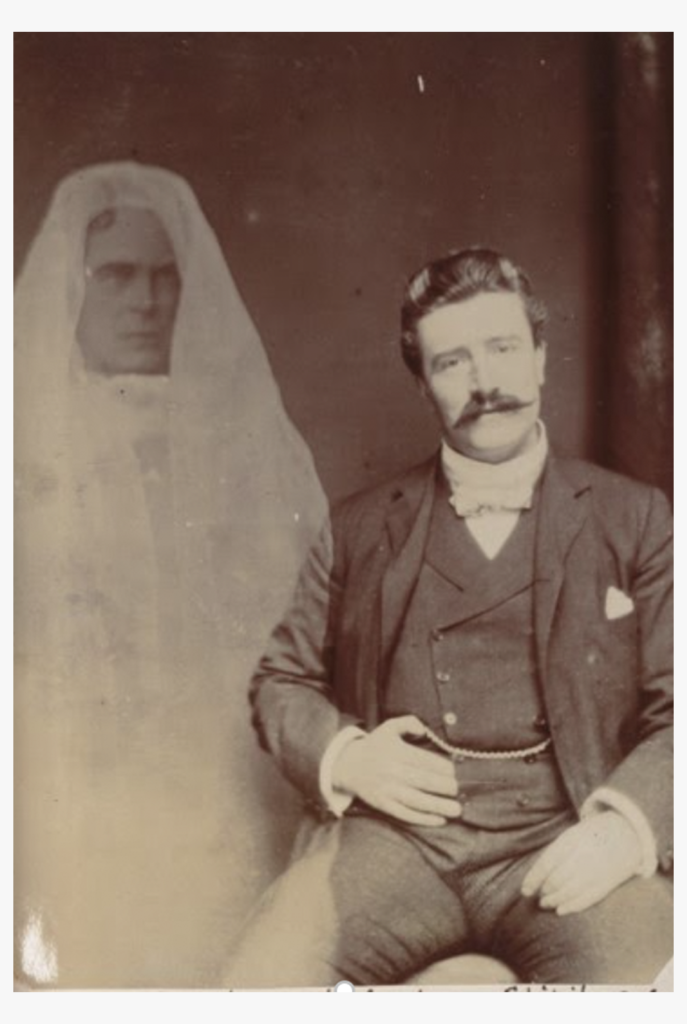

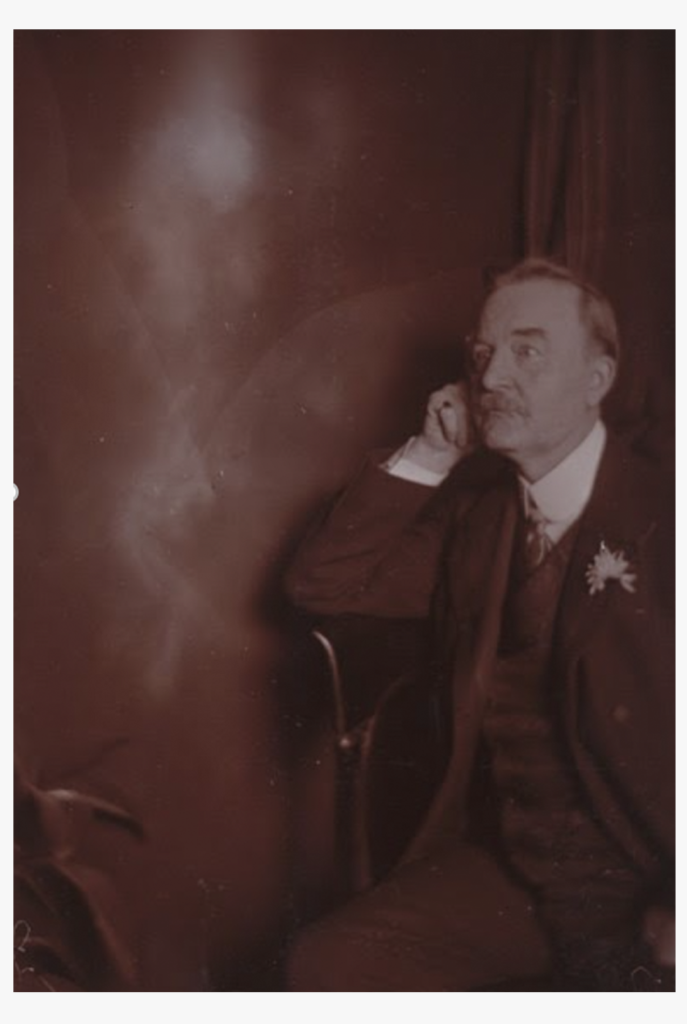

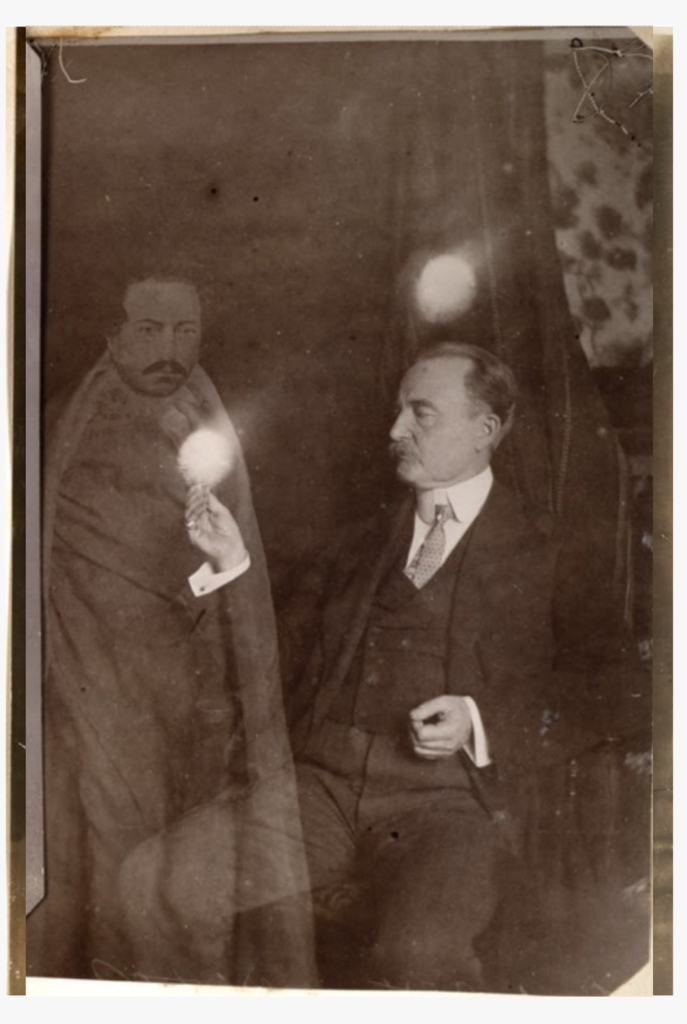

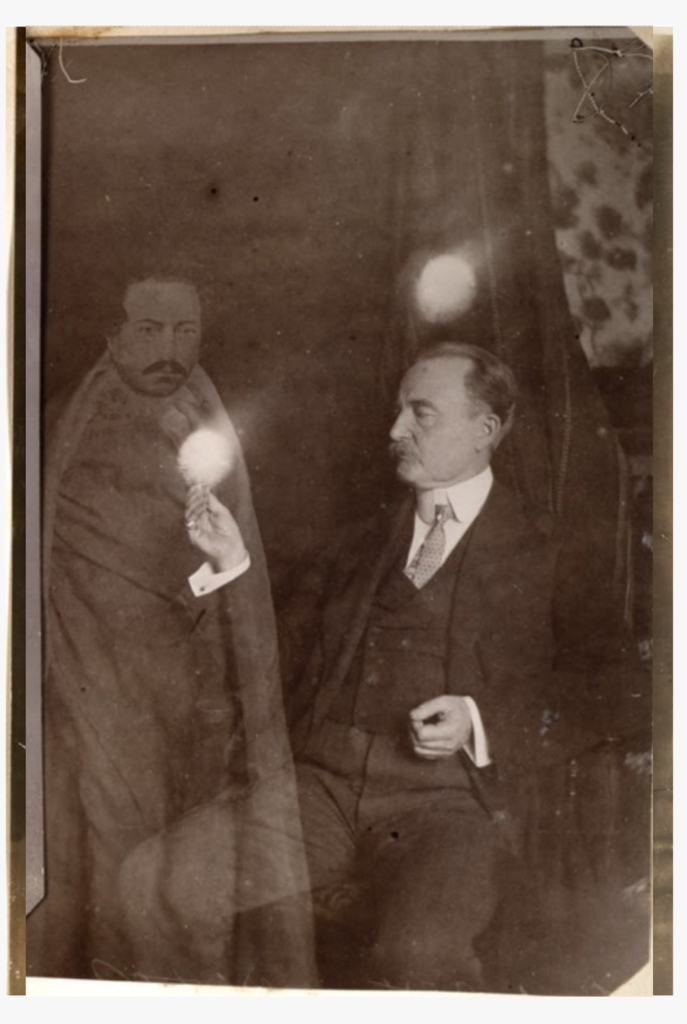

These circumstances yielded one of the more curious objects in SFMOMA’s photography collection: an album of “spirit photographs” that Dr. William J. Pierce assembled in 1903. Pierce lived in San Francisco and followed Spiritualism, a movement predicated upon belief that the soul survived after death and could continue to communicate with the living. The album is comprised of 274 pictures, many by Pierce himself, featuring subjects who are accompanied by gauzy, ghostly apparitions. Some of the transparent “spirits” look straight ahead and appear to lock eyes with their beholder, while others appear in profile. Many are indistinct and shadowy, as if hovering in space and unbound by gravity. Pierce and others who commissioned these pictures maintained that the photographs captured the presence of people who had crossed over into a spiritual realm.

Although detractors knew the images were products of technique rather than anything metaphysical, skilled photographers managed to convince many by shrouding their methods in secrecy. They created the appearance of these so-called “spirits” through a variety of means; some, like William H. Mumler—who famously produced a spirit photograph of Abraham Lincoln—used multiple techniques in combination.

During the printing process, the photographer could overlay multiple negatives to create the illusion of the sitter and a “spirit” occupying the same space. Another technique involved exposing a light-sensitized glass plate (or metal in the case of a tintype — a direct positive process requiring no negative) to the likeness of a “spirit” prior to photographing the sitter on the same plate. A model dressed in white could quietly pass behind the sitter as they were being photographed. The photographer could also smudge the glass negative; Mumler inadvertently created the first spirit photograph in 1861 when he made the darkroom mistake of using a plate that had not been sufficiently cleaned, resulting in what resembled a ghostly apparition in one of his images. In 1869, a trial against Mumler enlisted scientists and photography specialists to debunk his enterprise by demonstrating how the images could be produced through technical means. Mumler was acquitted, but the scandal damaged his reputation to the extent that he abandoned spirit photography.1 Nevertheless, the practice endured for decades, and its 20th-century defenders included Arthur Conan Doyle, who published The Case for Spirit Photography in 1922.

If we imagine the perspective of a Victorian-era viewer and consider the novelty of the medium, it is easy to understand why spirit photographs may have been convincing—and harder to characterize their buyers as gullible, easy marks. There is a near-universal desire to communicate with people from whom we are separated, and this idea appealed especially to those who were vulnerable or grieving. That same longing may account for at least some of the popularity of ouija boards, mediums, and ghost-hunting television shows today.

Spirit photographers could also exploit how, by the late 19th century, people associated photography with veracity in some contexts and the unexplained in others — a heady mix that made it challenging for viewers to know which pictures they could trust. While photographs were used to corroborate science or reveal the invisible (such as bones in an X-ray), they could also be misleading or display phenomena that did not resemble anything people actually saw in the world, such as the abstract streaks of light reflected off things in motion, known in the trade as blurs. Even now, the pictures we take on our smartphones contain unintended elements, such as lens flares.

Though spirit photographs may appear strange to our 21st-century eyes, they provide an extraordinary window into the belief systems and visual debates of people in the not-too-distant past, reminding us that the art of deception—and the desire to communicate with the spiritual realm—may never fade.

Notes

- For more on Mumler and spirit photography techniques, see Michael Leja, “Mumler’s Fraudulent Photographs,” in Leja, Looking Askance: Skepticism in American Art from Eakins to Duchamp (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 21-58.