Photo: SFMOMA

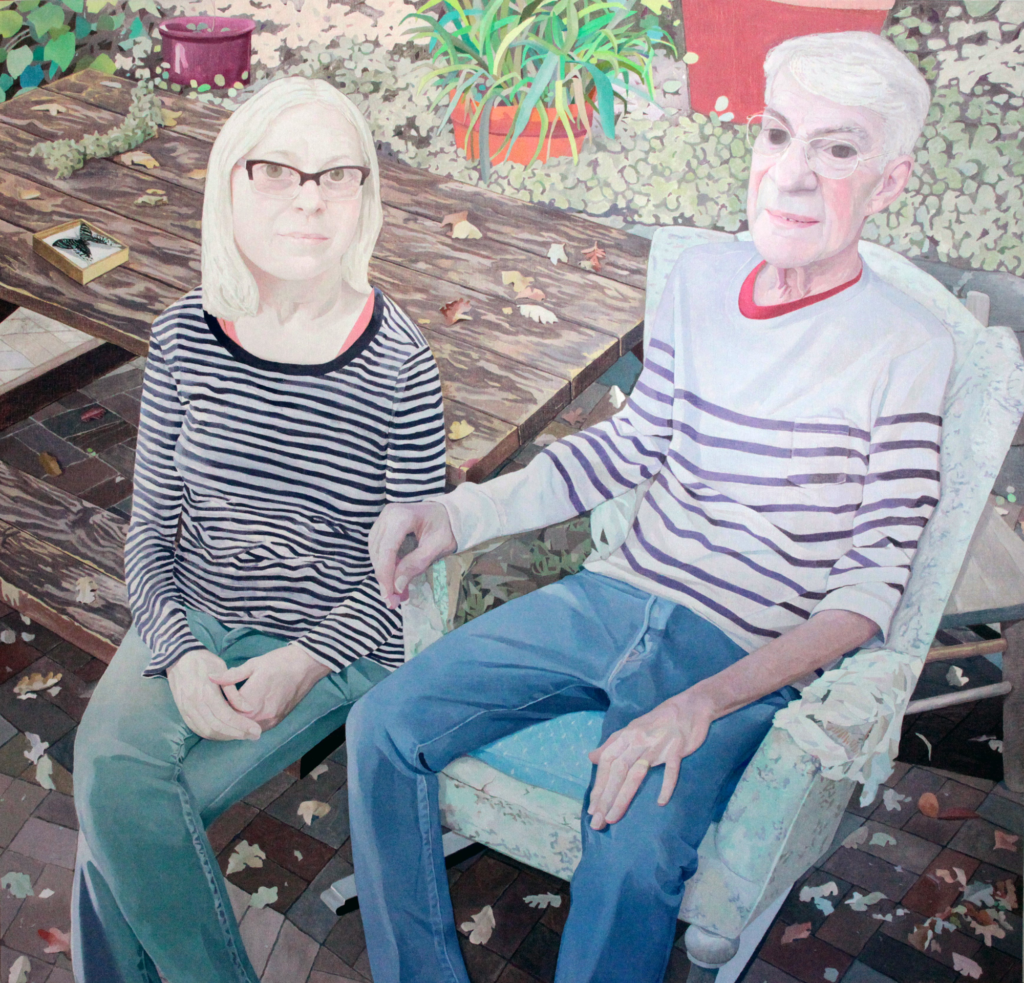

SFMOMA: We’re in your studio now, having a look at a work in progress for the upcoming exhibition Side by Side: Dual Portraits of Artists. It’s the one work in the show that is a new commission, and it pictures a father and daughter, Bay Area–based artists Richard and Alice Shaw.

Travis Collinson: I feel quite lucky to have been invited to be in the exhibition. David Hockney, whose painting Shirley Goldfarb + Gregory Masurovsky (1974) is the point of departure for the show, is one of my favorite artists. In my formative years, when I was learning to draw from observation, my junior college life drawing teacher Marc Romano brought in the monograph David Hockney: A Drawing Retrospective. So many of Hockney’s drawings are observation-based, and depict lovers, family. It was a major influence; I spent a lot of time with that book.

SFMOMA: How did you land on the idea to paint Richard and Alice Shaw?

TC: The curator, Sarah Roberts, and I had a little bit of back and forth, and I asked how the sitters were paired in the other works. She mentioned that there was already a husband and wife, and so on, and then I asked if there was a father-daughter combination, which I thought would be an interesting dynamic. With these two in particular, since both are artists, it speaks to continuation in terms of both familial legacy and artistic legacy. I already happened to know them, so it was easy: I called them up and they agreed to sit for me.

Photo: SFMOMA

SFMOMA: How do you know them?

TC: I worked for years for Paule Anglim’s gallery, and after Ruth Braunstein closed her gallery, Richard needed a place to show, so he started showing with Paule. And anyway, he’s been a figurehead in the San Francisco art community for a long time. He used to ride his bike to openings and carry it up the stairs into the gallery. I met Alice just around. It’s a small community in San Francisco.

SFMOMA: How did you start the project?

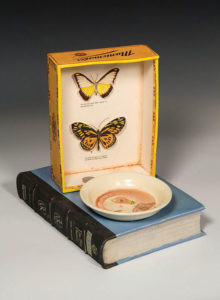

TC: In December 2016 I drove up to Fairfax and spent an afternoon with them. Richard gave me a little tour of the house and his studio. I noticed an old chair in the studio, and I had the idea to drag it outside to the garden, next to the picnic table, where we see Alice sitting. The garden is quirky, with a bunch of stuff in it, and I immediately felt it had a similar personality to Richard’s work—which is kind of funk and kind of junk, very assemblage and pieced together.

SFMOMA: The chair looks a little tattered.

TC: Yes, it’s likewise reminiscent of Richard’s thrift-store, found-material aesthetic. It is very much an artist’s chair. There’s clay dust all over it. The stuffing is falling out of the cushion. It’s a sculpture in and of itself. You can’t see it in the painting, but there are even C-clamps holding it together.

Travis Collinson, Lepidoptery Lesson (detail) in process, 2017; photo: SFMOMA

SFMOMA: Did you direct them on how to sit?

TC: I didn’t try to pose them too much. With portraiture, you want things to be natural, not overly composed. When people are comfortable, their personalities come across more truthfully. Part of what I like about this is that they are clearly engaging with me, but I’m not too overtly present within the portrait.

SFMOMA: Is it a coincidence that they’re both wearing striped shirts?

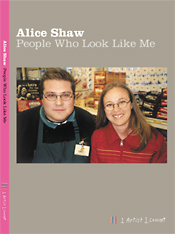

TC: Kind of no! It was a funny thing. Alice had a pink shirt on. We were getting set up. And then she said, “I brought a striped shirt, too, because I knew my dad was going to wear a striped shirt.” So she put it on over the pink shirt. Part of the reason it’s funny is because she made that book called People Who Look Like Me.

SFMOMA: What’s the story behind that?

TC: She took a series of somewhat odd, random photos of herself with other people, and in each case there’s a subtle similarity. And so this dual portrait now contains an homage to something she had done.

SFMOMA: Were you doing any sketching that day?

TC: No, no. With only a day, I only have time for photographs. You need to get as much raw material as possible to have enough to work from. At the photographic stage, my attitude is mostly scientific, observational. Then I come back to my studio and piece parts of the photographs together, to suit my needs compositionally.

Photo: SFMOMA

SFMOMA: I notice that the different areas of the painting are—subtly, but still—offering different points of view.

TC: It’s an artifact of my process—I’m taking a piece from one photo and a piece from another, and merging them in the same picture plane. Actually you can see similar effects in Old Master paintings, where the artist was working on different sections of the canvas at different times. Photoshop enables you to do it, too. You can take a hundred photos and piece them all together, blend them, and they look seamless—at first.

SFMOMA: It’s interesting that the preparatory drawing is just as large as the final painting.

TC: There were other drawings before this. I’ll do thumbnail sketches as a first step to work things out compositionally. At the stage we’re looking at here, I’ve been working nonstop for several weeks. I’m still at the anxious stage, where I can see things are starting to happen. The colors and the shapes are coming together.

Photo: SFMOMA

SFMOMA: I can see some of that resolution happening in the transition from this final preparatory drawing to the painting.

TC: Yes, the painting is more rich, more rounded out. The forms are more solid. Drawing is of course more linear, you’re trying to get the composition and the character and all the elements together. With the painting, you’re trying to get the picture space, the harmony of colors. And then the surface.

SFMOMA: So drawing and painting are more a binary in your mind, rather than one always necessarily being a step along the way to the other.

TC: Yes, two different things. For me at least. I mean, the drawing’s very important, as it provides so many of the compositional ideas for what the painting will eventually be. So you can’t have one without the other. But when you start to paint, it has to be its own thing, if for no other reason than because it’s a different material, a different medium, and it simply has its own qualities.

SFMOMA: So it’s almost like starting over.

TC: But you at least have a roadmap. You have a direction in which you’re headed, even if you still have to figure out the final destination.

SFMOMA: Do you prefer drawing, at the end of the day? It sounds like maybe yes?

TC: Yes. I love drawing. It just feels good. Painting is a lot more complex. It’s more mixing, and the colors have to be just right, and there’s constantly this back and forth I mentioned. With drawing, you just sharpen your pencil and go.

Photo: SFMOMA

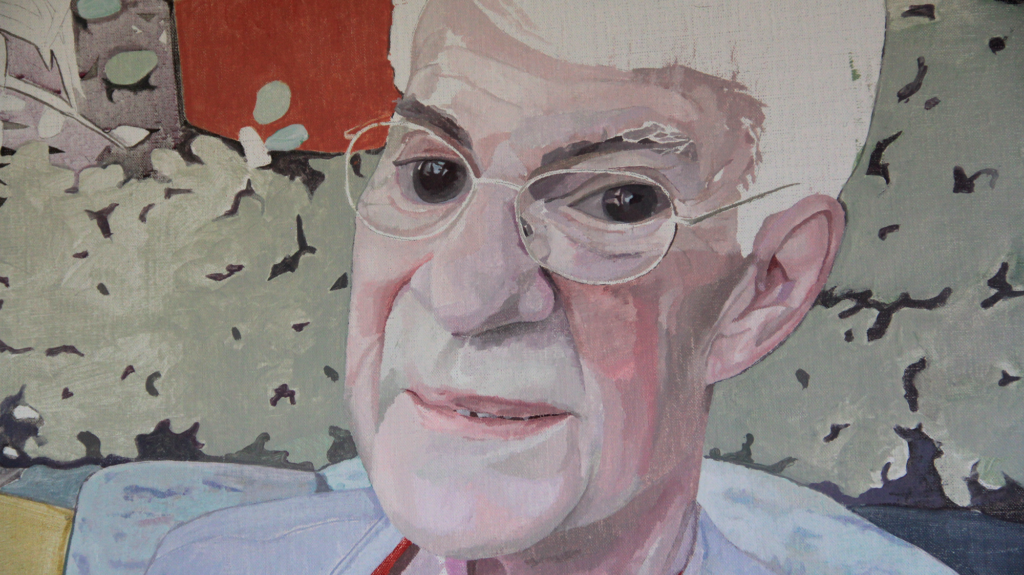

SFMOMA: In all your portraiture, there is always of course a strong resemblance to the subject, but there is also always a slight transformation—like the big eyes here—but that’s not all of what makes it diverge. Often it’s hard to put your finger on.

TC: When I started to become an artist, I came to realistic drawing through cartooning, since it’s what I grew up with. I certainly spent far more time watching cartoons than I ever did going to museums. Then as you get older and are exposed to different things, you realize there are different approaches. You can be literal, or you can go in a more cartooning direction as you try to seize on what makes the character the character.

Travis Collinson, Lepidoptery Lesson (detail) in process, 2017; photo: SFMOMA

SFMOMA: It sounds like you’re speaking on a couple of different levels, one more formal, and one more ineffable, having to do with personality.

TC: In art school, you learn not to look literally, but in terms of shapes, structure. Breaking things down into simpler shapes becomes the easiest way to see through the complexity of any kind of image. For instance, in the drawing here, I didn’t think Richard’s shoulders were exactly characteristic of him. If you know him, he’s very angular. So in the painting I’ve squared off the shoulders more, so the representation is more characteristic of his physicality.

With faces, it’s the same thing. A lot of times I’ll start with the eyes when I’m working on a new piece. And I suspect that’s primarily why they get bigger. It’s not at all how you’re typically taught. If you want to learn to draw realistically, you use proportional shapes to get the gesture of the figure, and then you place your details on top of those shapes. Whereas I’ll often start with the raw shapes and let them grow organically. I call them eccentricities: essentially they’re mistakes you embrace. I’ll think, “Ah, just because his face is a little longer, I’m not going to critique it if it seems right.” It enables you to focus on what you feel is essential to describing the character.

Travis Collinson, Lepidoptery Lesson (detail) in process, 2017; photo: SFMOMA

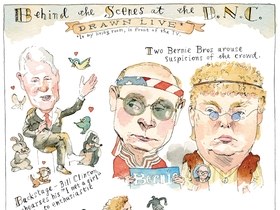

SFMOMA: That’s the power of caricature.

TC: Yes, great characterizations, like those by Barry Blitt in The New Yorker, can squish the face or break down the form and gesture to these almost iconic moments in terms of how you describe a person’s physicality, and still convey their essence. That’s the magic, that you can do so much with just a few lines or shapes.

SFMOMA: Have you done a dual portrait before?

TC: I’ve done paintings with more than one sitter, but not at this scale.

SFMOMA: How was it?

TC: It’s a lot of work! [laughs] You have to paint not one face, but two, as well as convey something of their relationship. So there are extra implications for their facial expressions, their body postures. I’m hoping that people will “get” that they’re father and daughter. It was quite a bit of work to get it just right, to pick the exact facial expressions.

Travis Collinson, Lepidoptery Lesson (detail) in process, 2017; photo: SFMOMA

SFMOMA: The way his hand seems to reach into her space without necessarily touching her seems to convey some affection, some comfort, without being too overt.

TC: I’m still rounding it out, but they feel comfortable to me, so I’m hoping that’s what the viewer gets a sense of. Like they’re in their own magic garden or something.

Travis Collinson, Lepidoptery Lesson, 2017; © Travis Collinson; photo: courtesy Anglim Gilbert Gallery