SFMOMA Content Producer Erin Fleming catches up with Tamar Avishai, collaborator for the Raw Material‘s recent podcast mixtape

It’s September 2020. I’ve been watching sports again, and it’s been…weird. There is something so uncanny-valley about the experience of cheering along to the familiar roar of the crowd while watching basketball teams compete, or seeing rows of fans look on as baseball players walk up to bat… and then remembering none of it is real. The cheers are sound effects and the people in the stands are cut-outs, literally made of cardboard. It’s a form of augmented reality for us and the players. But it reveals something so deeply ingrained in humans — we NEED that relationship of audience and performer. We need to feed off one another to feel motivated and connected and to truly come alive. Lately I’ve wondered if art is the same way.

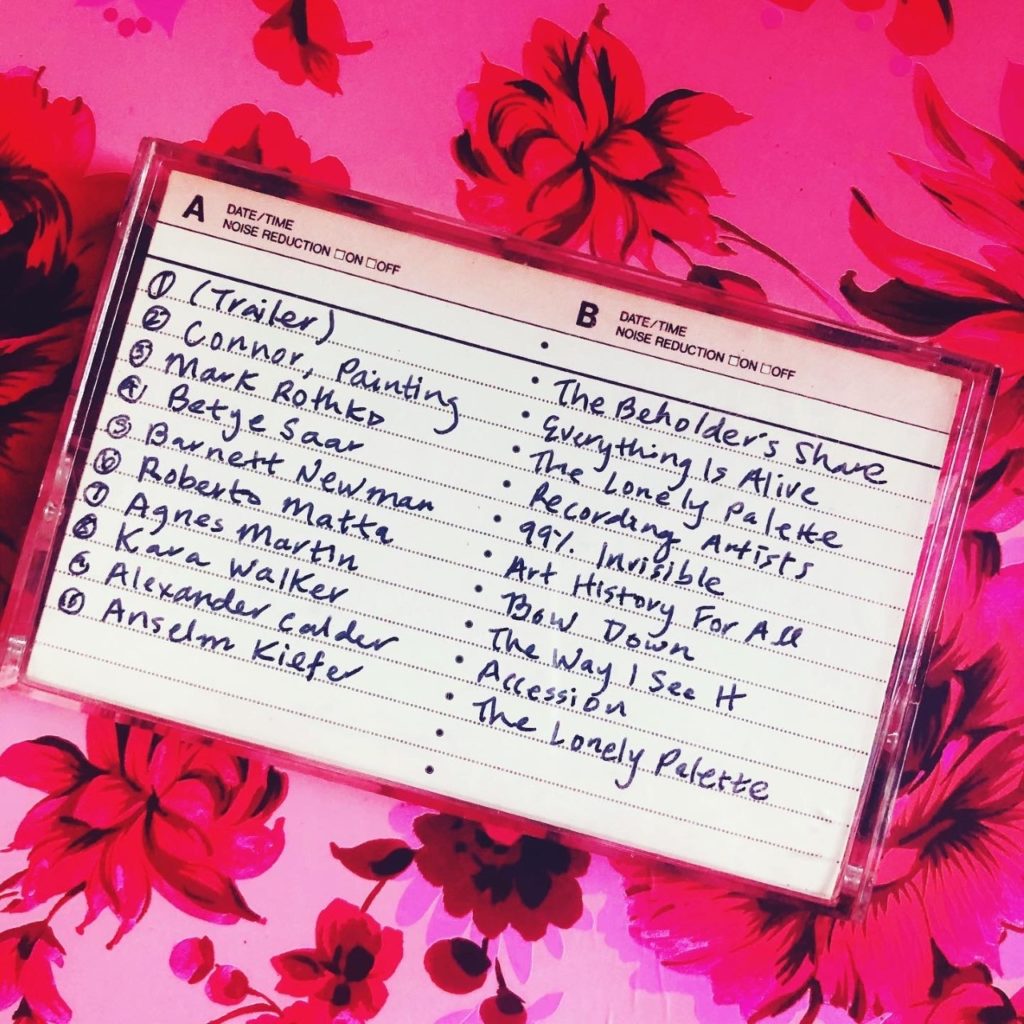

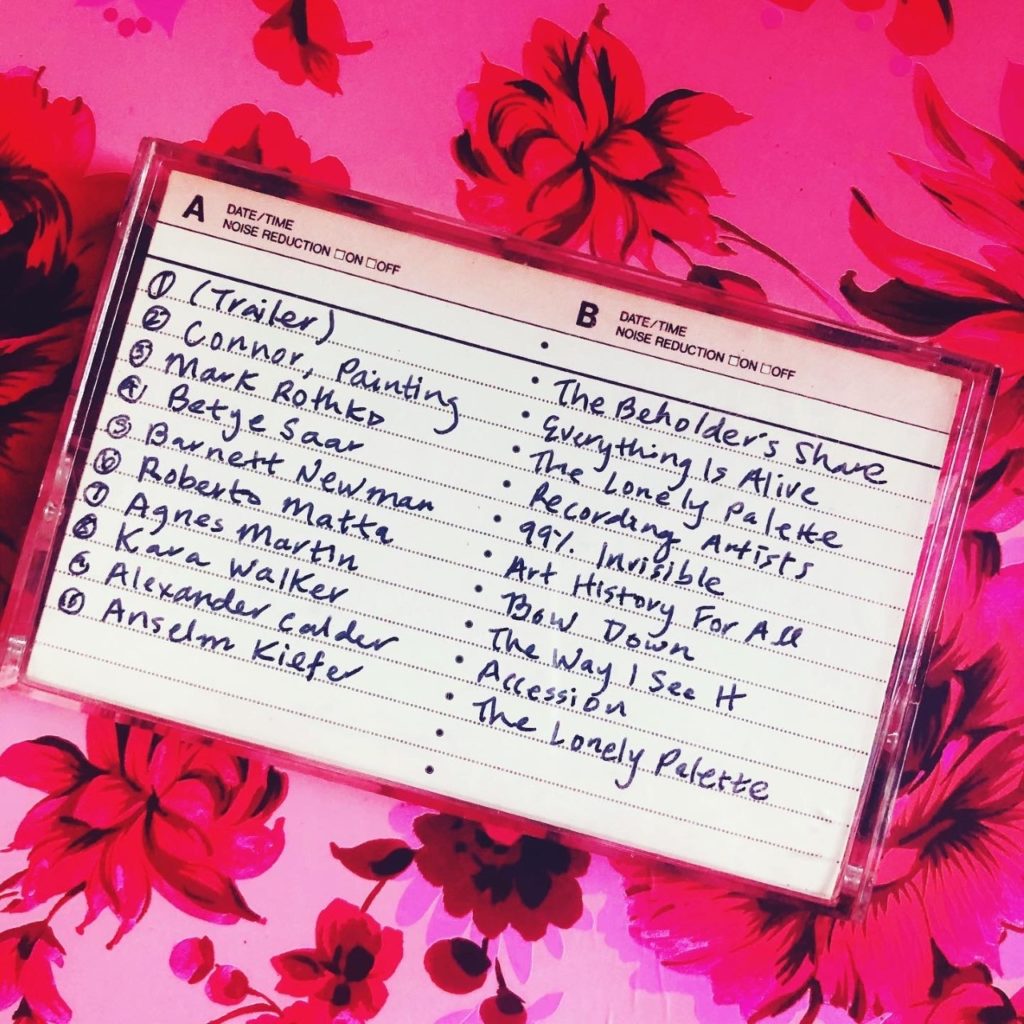

The most recent project from Raw Material, SFMOMA’s arts and culture podcast, explores that ache for connectedness. Created in partnership with Tamar Avishai, the Cleveland-based art historian and host of modern art podcast The Lonely Palette, the season is comprised of episodes about 8 artists in SFMOMA’s collection. Avishai calls her season “The Beholder’s Share,” and it was born from the unique challenges art-lovers face in our current “shelter-in-place“ reality, as we are unable to physically visit the paintings, sculptures, and works in museums that we turn to for inspiration, solace, and reflection. The works of art that give us life. But as Tamar reminds me, it’s a reciprocal relationship; we as viewers give life to those works of art. When we visit museums; we bring our own imagination, and in a sense, our interpretation activates the work and makes it come alive. For many artists, the impulse to create is also the impulse to share.

I miss visiting artworks in person. But when we consider how humans as “beholders” of art radiate and absorb meaning, can we imagine how perhaps the art might miss us in turn? Just like basketball players need crowds to roar, artworks need us to commune, cry, meditate, muse and dance in front of them. Aliveness happens through connection, and these episodes remind me that we’re still connected. Still alive.

I like to think that the art is alive, but in hibernation. Waiting wordlessly for us while we collectively work through a global pandemic and a long-overdue reckoning with systemic racism in our nation and in our beloved institutions too. When we do reopen, I dream that SFMOMA will be at the vanguard of a new approach to bringing art to people, and people to art.

Until then, we have this mixtape of stories about art to keep us company as we dream of those new futures. As part of our launch of the new series, I talked with Tamar about the “The Beholder’s Share,” and what it means to commune with artworks from afar.

Erin Fleming: Can you tell me about the title “The Beholder’s Share?”

Tamar Avishai: The “beholder’s share” is a concept from art theory by nineteenth-century philosopher Alois Riegl (popularized by his acolyte Ernst Gombrich) that fundamentally believes art is incomplete without a viewer. When you dive into the academic theory, it’s a fascinating (if involved) merging of art and psychology that evolved from turn-of-the-century Vienna, the heyday of the electrically charged psychological work of Freud and Egon Schiele.

But as it pertains to the average museum-goer joe, it’s just a really beautiful idea. It validates the personal, subjective responses we have to artworks that are so meaningful to us. It allows us to build meaningful relationships with these objects instead of dismissing them as intimidating or inaccessible. And it makes it all the more brutal that they’re hanging in darkened galleries right now, lonely and incomplete.

Is an “art podcast” an oxymoron? Why would someone want to listen to a story about something that is by nature meant to be experienced visually?

Oh man, if I had a nickel for every time I got this question! I understand why there is so much skepticism that art can be presented through an audio medium, but at the end of the day, so much about art history — and radio, for that matter — is in the writing, the description, the argument. We never stop to think how we could possibly read a book with no pictures, and I would argue that an art history podcast functions the same way. As a student of art history, I always learned best when I was told a really good story that helped place the artwork in context. It’s not just a lovely painting of sunlight and boats, it’s about the technological progress of Impressionist Paris that allowed for outdoor painting with liberated brushstrokes in real time. In this way, the painting itself is a byproduct, or even a portal, but hardly the whole experience.

That said, of course we still need the visuals. To that end, I’ve had great success starting my show with anonymous recordings of museum visitors describing artworks. It’s a super useful tool, both because it creates a fun mind’s eye visual for the listener, and because it makes it okay for the average visitor to trust what they see — which is a trickier feat than you’d think. So many people are intimidated by art, especially modern art. Often they think they’re not seeing what they’re supposed to. So if they hear someone on an art history podcast describe a Mondrian as looking like a computer screen or a Kandinsky like a pile of pick-up sticks, they can trust their own eyes and then think about why Mondrian might have favored pure precision and Kandinsky might have favored organized material chaos, and how that helps to explain their larger movements, respectively.

You recently said something about finding a “point of entry” for listeners to enter into a work. Why is this important?

Art history is all about the hook. Why do we care about this object? What is its greater significance in its movement, in its historical context, and how does it help us understand our shared humanity just a little bit better? I know I needed the hook when I was a student, and I know listeners need it now. I find that organizing the episode around a larger idea — a thesis, a point of entry — is what helps listeners connect to the object. Furthermore, it’s crucial in audio to accompany your listener along, making sure that they’re following the thread. Audio is a particular kind of storytelling because, as a listener, you can’t flip a few pages back to make sure you’re keeping up, and you can’t flip ahead to see if it’s worth staying for. You have to stay in the moment with the voice. So as the producer, it’s so important to make sure your argument is both clear and dynamic, and as an art historian, that comes from identifying a particular nugget of information that helps the listener appreciate why the story of this object is worth telling.

Many people cannot actually go to museums right now. Can podcasts fill that void, taking listeners on a journey of sorts? Should they try?

There is no substitute for the contemplative quiet of standing in front of an object in that airy, temperate gallery, seeing the lights hit the peaks and valleys of the brushstrokes. But as a native Bostonian, something I never realized until it was pointed out to me is that museums like the MFA in Boston or SFMOMA don’t exist in every city. It’s a luxury for art to be this accessible, and it was a worthwhile pursuit for educators to increase art’s accessibility even before museums shuttered during the pandemic.

The main difference between seeing the object in person and having it presented to you on a digital platform is, to my mind, how curated the visitor’s response is, for better and for worse. If you’re standing in front of Mark Rothko all by yourself, you can have an extraordinarily powerful personal reaction that might not be connected to the artist’s intention at all, or you can give it a glance, decide it’s inaccessible, and walk away. If you listen to the podcast episode on Rothko, you miss out on experiencing the artwork on your own, but you can’t help but learn something about the context, which might make you more curious to seek out an original the next chance you get. But it also might color your response when you do.

I also think the beauty of podcasts in this boom we’re currently in is that listeners trust that pods are always entertaining, even if they’re about a subject they might have previously dismissed as boring or esoteric. People are just willing to generously extend their curiosity to the subject. So even if you might have a hard time dragging that person to the art museum, they’re much more willing to listen to an art history podcast, and that’s a really valuable way to get them excited about art.

What was it like to rifle through dozens and dozens of podcast episodes about art?

It’s been bliss listening to all the most innovative and articulate art and design podcasts out there and winnowing the field for our mixtape. What makes these episodes unique is that they’re not just created by art professionals, but by audio producers — they understand what makes a compelling story, a compelling interview. They understand how to make this art sing, and all in completely different ways. I think other disciplines would be wonderfully served to mirror this kind of roundup. Plus, I’m so grateful to have had the opportunity to reach out to creators whom I admire and find out — sheepishly — that they listen to my show too. It’s a pretty great feeling.

Your new episode on Anselm Kiefer considers large scale communal trauma. Do you see any parallels or reflections that relate to today’s climate?

I absolutely do, in a few different ways. As I was writing about Kiefer in the context of how we try to understand a traumatic event, and therefore commit it to a representational medium like art or poetry, I found myself thinking about the pandemic, and how incomplete all of our idiosyncratic experiences are, and how, in Kiefer’s words, “desperate” it is to not know the outcome or be able to talk about it in a whole or complete way. As a collective, we don’t know how this will end. We don’t know how to process death on a mass scale, or even an individual scale — trauma and grief sneaks up on us even when we think we’ve moved on.

I also found myself struck by the idea of moral clarity, and how seductive it is. Kiefer’s work runs in such adamant opposition to the idea that the experience of an individual can ever be completely knowable, to themselves or to others, and this helps to debunk the idea that experience itself can ever be black and white, even though the world would be so much easier if it was. Kiefer doesn’t see his work as pushing any kind of post-Holocaust representation agenda. He values a nuanced eye and invites his viewers to take pleasure in unearthing layers. He’s not striving for moral clarity or pitting good against evil. As a first-generation postwar German, that kind of crude narrative — atoning for the sins of his father — has never served him well.

And I don’t believe it serves anyone well, especially in our inflamed current climate. We’re divided as a country, and even divided within our “sides,” and I think we need to appreciate that living in a world of moral uncertainty is scary, and also a privilege. It would take an unequivocal, catastrophic evil to put us all in the moral right, and the world simply isn’t as unnuanced as that. Which means that I, for one, am trying to listen more, to people I agree with and people I don’t, and appreciate the productive commonalities in the shades of gray.

Listen to “The Beholder’s Share” here.