Ray and Charles Eames selecting slides for a three-screen slide show, 1970; photo: © Eames Office

“Whether it’s a house or film or chair — it must have a structural concept.”

Charles and Ray Eames were design visionaries. Creating architecture, furniture, graphics, and multimedia from the 1940s through the 1970s, the couple pioneered the playful, multidisciplinary, and user-centered approach that has come to define California design. In 1989, SFMOMA acquired the entire contents of the conference room from the Eames Office, which they occupied for over 45 years. A mix of collectibles and seemingly mundane audio-video equipment, the conference room is an incredible artifact of a less well-known aspect of the Eameses’ work — an effort to leverage design and technology to promote communication, share knowledge, and inspire creative producers. In preparation for the exhibition Designed in California, we are revisiting the Eames Office Conference Room as part of a larger exploration of how California designers have significantly transformed the way we work and live.

The Eames conference room; collection SFMOMA; gift of the Architecture and Design Forum; photo: Tom Bonner

We’ve been aided in our exploration of the conference room contents by Llisa Demetrios, the Eameses’ granddaughter and registrar of the Eames Collection. Through Llisa we can decode the lettering and numbering on various modified film-and slide-projection equipment, and understand the conference room as a dynamic working space, where the Eameses would review media for upcoming multichannel projection presentations — information environments including rich visuals, sound effects, music, and even smells. Llisa notes that the room brought the Eameses’ many fascinations together: “Thinking about the conference room takes me back to being a young girl sitting in the Eames airport tandem seating and watching a three-screen slide show or short films, such as Atlas: The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire. I always loved the visual richness [of the objects] in the room, and then the lights would dim and then there would be a richness in their films.”

A partial reconstruction of the Eames Conference Room at SFMOMA’s Collections Center, 2017; photo: Katherine Du Tiel

The Eameses are widely recognized for their early experiments in plywood furniture and the design of their own home, constructed from prefabricated materials as part of the iconic Case Study House Program. The couple were design magpies, juxtaposing the latest in modernist tools with craft, folklore, and details of daily life drawn from their travels around the world. These interests are clear in the conference room, where wooden toy tops, shiny Mexican milagros, and wallpapered switch plates are drawn together in a reflection of the couple’s exuberant curiosity.

However, the Eameses also worked at the cutting edge of a burgeoning technological landscape. They collaborated for decades with technology giant IBM to produce exhibitions, films, and graphics that educated the masses about the then-new computer. Through this work, they became sought after for their skill in making technology humane, exciting, and accessible.

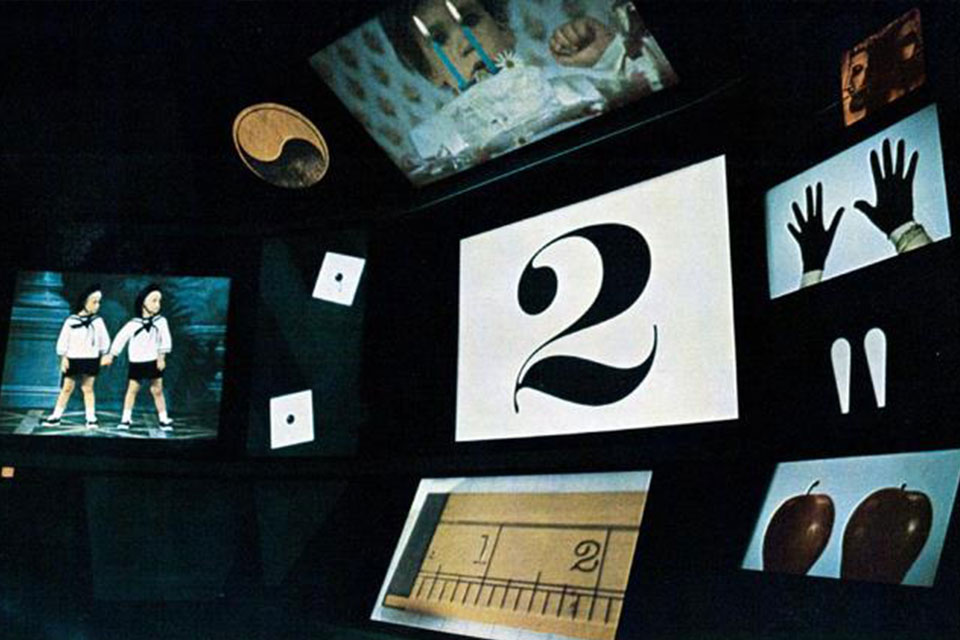

Recognizing these information environments as projects the Eameses approached with the same sensibility and drive as their architecture and furniture provides a richer understanding of their unique design practice. As Charles Eames stated, “Whether it’s a house or film or chair — it must have a structural concept.” The Eameses’ films and projection presentations translated their analog juxtaposition of objects, images, and ideas into the realm of media and technology. One of the studio’s most ambitious multimedia projects was Think, a 22-screen presentation created for the IBM pavilion at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair. Immersing viewers in a kaleidoscopic mix of photographs, film clips, and narration, Think outlined the shared dynamics of human and computer communication and problem solving.

Think playing in the Information Machine theater at the IBM Pavilion, New York World’s Fair, 1964; Photo: © Eames Office

In many ways, works like Think anticipated the multimedia environments we live in today — information spaces where content is freely accessible and continually recombined. The Eameses also predicted the user’s place at the center of this landscape, as a content creator sharing and selecting knowledge and experience. In their vision, communications technologies should create an open exchange of information for the production of informed citizens. As they presciently argued, “The ‘problem’ our society faces is not so much a lack of scientific, or technical, or even sociological knowledge — it’s a lack of ways of transmitting existing knowledge to people as they need it, in forms they can readily grasp.”

The Eames Conference Room will be on view in Designed in California, through May 27, 2018 on Floor 6.