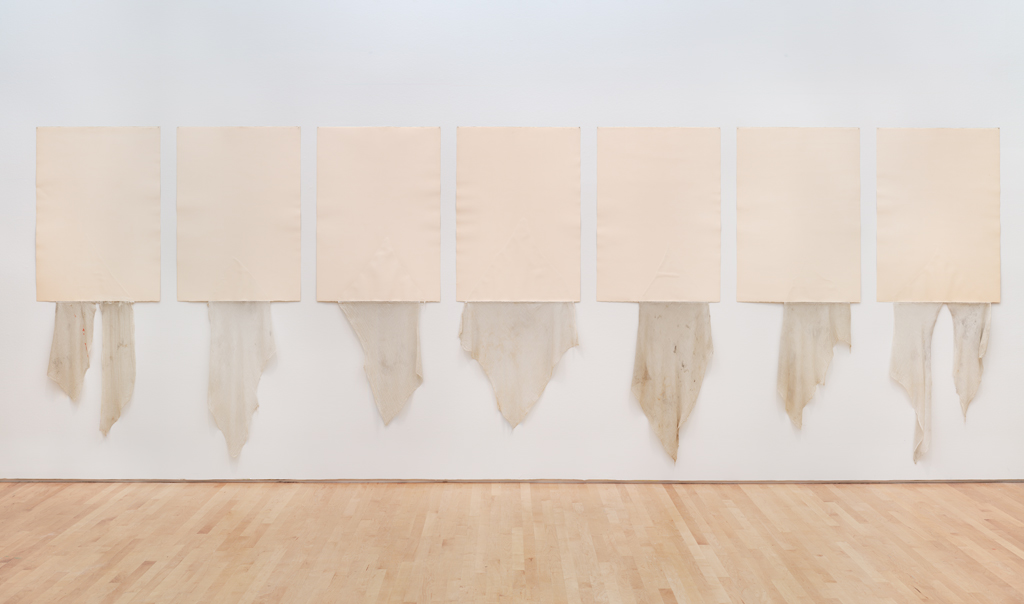

Robert Rauschenberg’s Pyramid Series (1974) consists of seven units of embossed paper and fabric, each of which is nearly two and a half feet wide, while the tallest is more than six and a half feet high.1 Each is constructed of two sheets of Arches paper and a cheesecloth rag that was used previously in the artist’s printmaking studio. The juxtaposition of the purity of the white, rectangular sheets of paper and the stained, irregular pieces of the cheesecloth simultaneously embodies the artist’s characteristic responsiveness to his materials and reflects his global concerns. Throughout Rauschenberg’s career, his art alternated between works filled with images and works like those in the Pyramid Series, which were largely devoid of imagery. Among his most significant creations of the latter type were his White Paintings (1951), canvases that act as receptors for external events.2 Around the time the Pyramid Series works were created, the events of greatest concern to the artist were global in nature. He had long been committed to promoting international peace, and believed that his art could have an influence on the world stage. Between 1965 and 1970 Rauschenberg had devoted considerable attention to the civil rights and antiwar movements in the United States, often engaging in political activism through projects such as the CORE Poster (1965) he created for the Congress of Racial Equality.3 It was in the 1970s that his concerns extended decidedly to the international sphere. This focus culminated in his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI), an initiative conceived and executed between 1984 and 1991 through which an exhibition of his work traveled to various politically charged regions.4

The Pyramid Series was strongly influenced by Rauschenberg’s experiences in the Middle East in the 1970s. In the late 1960s he had been introduced by Senator Jacob Javits to Israel’s foreign minister Abba Eban.5 Through Eban, the artist met Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan of Egypt, who served as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Eban invited Rauschenberg to Israel, and Prince Sadruddin invited him to Egypt.6 Before the trip could take place, however, the Yom Kippur War broke out. In October 1973, Egyptian and Syrian forces entered the Israeli-held Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, the area that had been captured during the 1967 Six-Day War. In response, the United States and the Soviet Union initiated massive material support for their respective allies, and the two nuclear superpowers were forced to the brink of confrontation.

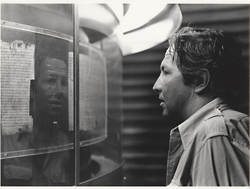

2. Robert Rauschenberg standing in front of the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 1974. Photo: Nir Bareket; © Nir Bareket (www.nirbareket.com)

Rauschenberg completed several new works following the war, including the Early Egyptian Series (1973–74), box structures covered in glue and sand that resemble Egyptian temple pylons, and the Egyptian Series drawings (1973), which feature as collage elements crushed paper bags and bits of cheesecloth. In May 1974, six months after the war’s end, the artist traveled to Israel for three weeks to prepare for an exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (fig. 2). With Robert Petersen, Hisachika Takahashi, Mayo Thompson, and other colleagues, he explored archaeological sites, examined the Dead Sea Scrolls, toured the surrounding desert, visited Arab settlements, and saw military vehicles that had been destroyed during the Yom Kippur War.7 For the exhibition, Rauschenberg created Made in Israel, six three-dimensional constructions named after places he had collected desert sand, and five mixed-media drawings called Scriptures.8 Soon after returning to his studio on Captiva Island, Florida, in June 1974, he completed Tablets for Israel and the Pyramid Series.9 Significantly, these postwar works represent both Israel and Egypt. Taken as a group, they comprise Rauschenberg’s material responses to the cultures of each country as witnessed in their geography and physical monuments. Rauschenberg looked beyond the conflict and political differences that dominated the two nations in the mid-1970s and focused instead on their shared history as repositories of civilization, emphasizing their potential for peaceful coexistence.

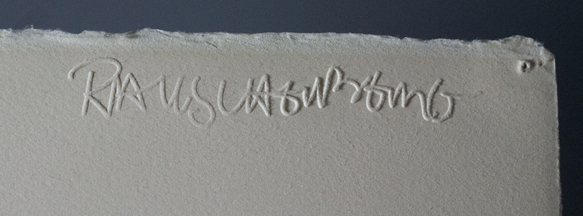

To create each unit in the Pyramid Series Rauschenberg folded a portion of the cheesecloth in a triangular pattern and sandwiched it between two sheets of paper that he had coated with an adhesive, allowing the remainder of the cloth to hang below the edge of the paper. He then ran each unit through a lithography press, forcing the paper together in an action that sealed the adhesive and embossed the triangular outline of the folded cheesecloth into the paper in a manner reminiscent of a print plate mark. (The artist’s signature is also embossed in the upper right corner of each work [fig. 3].) This process took place at Untitled Press, Inc., a print workshop Rauschenberg established at his Captiva Island studio in 1971 with the assistance of Petersen. The venture was modeled on the groundbreaking Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), the studio founded by Tatyana Grosman in her Long Island garage, where Rauschenberg made his first prints.10 Rauschenberg’s first press, a nineteenth-century Fuchs & Lang lithographic press, was given to him by a neighbor and restored by Rauschenberg, Petersen, and Takahashi. Rauschenberg named it “Little Janis” in honor of rock singer Janis Joplin, who like Rauschenberg had been born in Port Arthur, Texas.11 Untitled Press was used extensively by Rauschenberg and also hosted visiting artists, including Cy Twombly (1928–2011), Brice Marden (b. 1938), Susan Weil (b. 1930), and Robert Whitman (b. 1935). Between 1972 and 1973, on the advice of Twombly, Rauschenberg purchased a larger Griffin motorized lithography press that he named “Grasshopper” for its shape and green color. The dimensions of the Pyramid Series works suggest that they were embossed using this larger press.12

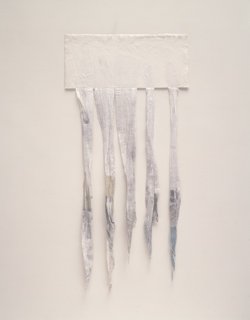

Always present in print ateliers, cheesecloth is typically used to clean ink from lithographic stones. Petersen recalls Rauschenberg commenting on the “beauty” of cheesecloth rags that were hung to dry on lines around the perimeter of the Untitled Press studio.13 In addition to admiring the chance shapes and transparency of the cheesecloth scraps, Rauschenberg was interested in the ink stains they carried, as those markings contained the history of their use.14 In the Pyramid Series works, the act of producing embossed, pyramid-like triangular shapes by passing the materials through the press embodies a melding of diverse parts: the stained cheesecloth and the clean, white paper. Rauschenberg’s interest in this process led him to create other works similar to the Pyramid Series, in which some of the cheesecloth rags display more visible traces of ink (fig. 4).

Petersen recalls Rauschenberg’s decision to join cheesecloth and paper in these works as a seemingly spontaneous and intuitive response to the materials available in the studio.15 Further, he believes that the title of the series, inspired by the embossed shapes, came about after the creation of these works was well underway. Following the Yom Kippur War and his subsequent trip to Israel, Egypt was on Rauschenberg’s mind, and in 1973 Marion Javits, the senator’s wife, had given him a book on the ancient Egyptian pyramids that fascinated him.16 These loose yet compelling connections are characteristic of the “chains of associations” that the artist often made during the working process.17

A similar flexibility is seen in Rauschenberg’s approach to the order in which the seven Pyramid Series works should be installed. In response to a 1998 letter from Gary Garrels, then SFMOMA’s Elise S. Haas Chief Curator and Curator of Painting and Sculpture, Rauschenberg simply wrote, “I prefer they all be shown together. There is no formal regulation about the order. Depending on the space one ‘line-up’ looks better than another—play by eye.”18 This comment reflects his desire to keep the Pyramid Series alive to the moment, a wish that also dictated his work’s responsiveness to contemporary political and cultural conditions and his own adaptable working process, which favored immediacy and interaction with the materials in his studio.

Notes

- Rauschenberg considered each unit to be an independent artwork, although they are typically exhibited together in groupings of five or more. The works are referred to individually as Untitled (Pyramid Series). The artist created another Pyramid Series, also consisting of seven individual units, all of which are now in the collection of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

- In 1973, the White Paintings were exhibited at Ace Gallery, Venice, California. The approach Rauschenberg took in those works was likely fresh in his mind when he began the Pyramid Series. Notably, the Pyramid Series also responds to the Minimalism of the mid-1970s, as do other Rauschenberg works such as the Cardboards (1971–72). While both series incorporate shaped structures and serial formats that are hallmarks of Minimalism, they assert their handmade character, their use of everyday materials, and the presence of the artist’s hand—elements absent from much minimalist art.

- For a selection of Rauschenberg’s political activities of this period, see Joan Young with Susan Davidson, “Chronology,” in Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective, ed. Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 565.

- For more on ROCI, see Jack Cowart, ed., Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991).

- Cowart, Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange, 573, and Mary Lynn Kotz, Rauschenberg, Art and Life (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 194.

- Robert Petersen remembers Eban visiting Rauschenberg’s New York studio accompanied by armed security stationed outside the door. Robert Petersen, interview with the author, February 23, 2013, Tivoli, New York.

- Images of Rauschenberg and his colleagues in Israel are featured in Robert Rauschenberg in Israel (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1975). Thompson recalls Rauschenberg going to Eban’s home, discussing the recent war, and commenting that the last time he and Eban met was in New York during a time of peace. He also remembers brief meetings with Shimon Peres, then Israel’s minister of transportation, and Teddy Kollek, then mayor of Jerusalem. Rauschenberg and his colleagues visited Jericho and Bethlehem and frequently discussed the differences they perceived between Israeli and Arab culture. According to Thompson, Rauschenberg was fascinated by the facsimiles of the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Israel Museum. Thompson notes that the group also visited a Bedouin settlement in the desert. Mayo Thompson, telephone interview with the author, March 12, 2013.

- Kotz, Rauschenberg, Art and Life, 195.

- Rauschenberg also continued work on his Early Egyptian Series after returning to the United States, completing it in 1974 as well.

- Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson, eds., Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 572. Petersen has discussed the establishment of Untitled Press and Rauschenberg’s astonishment at his good luck that a lithographic press would already exist on tiny Captiva Island. Petersen, interview with the author, February 24, 2013.

- The lithographic press was later given to Petersen by Rauschenberg when Petersen moved north from Captiva. The press had not been operational since the 1990s. On February 23, 2013, Petersen, his daughter Lena Petersen, and the author reassembled Little Janis, and Petersen demonstrated the printing techniques used to create the Pyramid Series.

- The bed of Little Janis measures twenty-four inches, while the bed of Grasshopper measures thirty-eight inches. Robert Peterson, email to the author, April 2013. The dimensions of all the pressed units in the Pyramid Series exceed twenty-four inches, suggesting that Grasshopper must have been used to create them.

- Petersen, interview with the author, February 23, 2013.

- Petersen recalls that Rauschenberg did not allow paper-drying racks to be installed at Untitled Press because he liked to watch the prints dry as they hung on clotheslines, blowing in the wind. Petersen also remembers Rauschenberg commenting on his interest in clothing drying on a line. Rauschenberg’s observation that the cheesecloth retained traces of the lithographic images led to his Hoarfrost series (1974–76), in which he used solvents to transfer images onto unstretched fabric.

- Petersen remembers that Rauschenberg very seldom gave verbal instructions at Untitled Press. Instead, he silently began to work with the materials at hand, and his collaborators understood from his actions the necessary follow-up procedures. Petersen, interview with the author, February 24, 2013.

- Kotz, Rauschenberg, Art and Life, 194. Petersen recalls seeing the book on Egyptian pyramids in the studio, although it has not been specifically identified.

- See chapter 1, “Studio Practices,” in Robert Saltonstall Mattison, Robert Rauschenberg: Breaking Boundaries (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003).

- Rauschenberg’s response is handwritten on the letter sent by Garrels dated November 10, 1998. SFMOMA Permanent Collection Object Files: Pyramid Series, 98.300.1–7. An additional facsimile transmission to Garrels from David White, then curator of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, dated November 17, 1998, and sent from Bilbao, Spain, suggests another possibility: “Although [Rauschenberg] considers them a suite of drawings, it is not necessary that they all be exhibited at once. You may have noticed that only six are reproduced in the catalog of the retrospective.” See Hopps and Davidson, Retrospective, 352–53.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette College, Easton, PA

Photo courtesy of Lafayette College, Easton, PA