Untitled (ca. 1955)1 employs a vocabulary typical of Robert Rauschenberg’s works of 1955–58. A stretched canvas forms the work’s primary structure; loosely applied paint, punctuated by an isolated cluster of thick, frenetic paint strokes, consolidates multiple layers of paper and fabric fragments, concealing much of the surface. The canvas sits in a box-like wooden frame; attached to its lower left edge is a small shelf on which an upright metal funnel is perched. Together, the frame, funnel, and shelf push away from the wall and toward the viewer. Their three-dimensionality creates the blurring of artistic boundaries that defines the Combines,2 a series of assemblages Rauschenberg made between 1953 and 1964 that merge collage, painting, and sculpture. Yet in the modestly sized Untitled (ca. 1955), the near total subordination of the assemblage elements to an allover coating of green-gray paint, disrupted most visibly by the open sweatshirt neckline attached near the top center of the canvas, marks a decidedly distinctive approach. In the context of the Combines as a whole, Untitled (ca. 1955) is subdued and anomalous, as though during a moment of introspection Rauschenberg had briefly stepped sideways into darker territory. In contrast to the usual expressions of garrulous exuberance seen in the Combines, Untitled (ca. 1955) carries on a more meditative, internal dialogue.

One of the least well known of Rauschenberg’s works from the 1950s, Untitled (ca. 1955) has received scant attention in the literature, and until the retrospective that opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1997, it had never been shown.3 One reason for this disregard seems to be that the funnel became detached from the piece and went missing for a number of years (fig. 2). Although the funnel reappeared in the storage area at the artist’s studio sometime in the early 1980s and was reattached, the work remained in Rauschenberg’s possession until it was acquired by SFMOMA in 1998.4 The string that runs from the top of the canvas to the skein gathered inside the funnel, once continuous, also broke at some point. Consistent with his hands-off attitude toward the aging of his work, the artist chose to repair it simply by tying the two frayed ends in a knot. Similarly, Rauschenberg chose not to address the small puncture hole in the opening of the shirt neckline, which does not appear in early photos of the artwork.5

The canvas started out as part of the Red Paintings, a series of predominantly red canvases collaged with scraps of fabric and paper that Rauschenberg produced in 1953–54.6 Brilliant red paint remains visible in the gap between the canvas and the wood that frames it (fig. 3) as well as in slight fissures across the painted surface. In the early 1950s, Rauschenberg frequently reused canvases. In this case, the process of transforming the Red Painting included covering the existing red elements with a flat coating of dark paint and adding a number of new elements, such as the funnel, assorted newspaper scraps, the detached shirt cuff along the far right edge near the top of the canvas, and the worn sweatshirt that dominates the top of the composition. The green-gray hue of the paint is curious, hovering between an Army green and a dark gray, a color that does not appear in any of the other Combines. Notably, Rauschenberg applied a single color of paint almost uniformly, making the work’s surface more similar to that of the Black paintings and the Red Paintings than it is to that of the Combines, which typically feature a patchy application of numerous colors of paint. The few paper scraps that remain uncoated in Untitled (ca. 1955) include a prayer card printed with an image of Christ, a picture of two shirtless men (likely boxers) that appeared on the front page of the New York Daily News, and a tide table for Sandy Hook, New Jersey. The funnel partially blocks another newspaper photo that shows a flooded bridge alongside fragments of a caption, now barely readable through the paint: “Complete W” (perhaps washout?) and “victim of rains, melting.”

4. Robert Rauschenberg, Door, 1961. Oil, fabric, wood, painted sign, stenciled letters, paper, undershirt, paint can lids, string, and rock, with bottle caps and miscellaneous objects under chicken wire, on plywood with frame, 88 1/2 x 37 x 7 1/2 in. (224.8 x 94 x 19.1 cm). Philippe Durand-Ruel Collection, Paris; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

When encountering the disparate elements in Untitled (ca. 1955), as with all of Rauschenberg’s Combines, one is tempted to find some kind of narrative: for instance, are the tide table and the image of flooding meant as a wry juxtaposition to the funnel, which is capable of handling only a trickle of water? However, this Combine resists the narrative impulse more than most, yielding little more than atmospheric and physical associations, and projecting a muteness reinforced by its lack of a title.7 Many elements of the work—its drab color, the photo of the boxers, the humble sweatshirt, the galvanized metal funnel, and the plumb line of the string—combine to lend Untitled (ca. 1955) a workaday, mundane air. The sweatshirt, with all its connotations of everyday casualness and comfort and its association with sports, is particularly notable for its prominence within the composition. Rauschenberg began to include pieces of clothing frequently as he moved from the earliest Combines, such as Collection (1954/1955) and Charlene (1954), into the flow of the Combines proper. Many of these items are tacked on in their entirety; in a number of works, neckties, socks, and even a hat and an ankle brace lie flattened but uncut.8 Several works include shirts, notably Charlene, Double Feature (1959), and Door (1961, fig. 4).9 Rauschenberg also incorporated cut bits of apparel, particularly shirt cuffs and pockets, and occasionally sleeves. These small pieces make shorthand reference to their source garments, with some remaining quickly identifiable and others so fully embedded in the work’s surface that they are hard to distinguish. Throughout the Combines, clothing items tend to meld into the overall compositions and participate in the democratic, leveling play of materials that characterizes these works. The sweatshirt in Untitled (ca. 1955) is dealt with quite differently. Neither left whole nor radically fragmented, it is cut and spread open like a hide stretched for tanning. The slightly loose neckline acts as a compositional focal point, lifting away from the work’s surface at roughly the spot where a sitter’s head might appear in a conventional portrait. While Rauschenberg’s deployment of clothing always introduces a tactile, physical suggestion of the human body, nowhere is this more apparent than in the flayed sweatshirt in Untitled (ca. 1955). When the work is hung on the wall, the neck opening of the sweatshirt beckons at just about head height, inviting us not simply to consider its owner, but also to imagine slipping into its worn cotton contours ourselves, asking us, in other words, to contemplate the intimate experience of wearing someone else’s shirt.

5. Alberto Burri, Sacco 5P, 1953; burlap, acrylic, Vinavil, and fabric on canvas, 58 3/4 x 51 in. (149 x 129.5 cm); Città di Castello, Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini; © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Untitled’s skin-like surface and the aperture formed by the sweatshirt collar resonate visually with Alberto Burri’s (1915–1955) Sacchi series, particularly works such as Sacco 5P (fig. 5) and Sacco, both of 1953.10 Both Burri and Rauschenberg incorporated raw materials from everyday life in order to infuse their work with realism without resorting to figurative representation, yet Rauschenberg allowed his materials to retain their own identities to a far greater degree. Although the ragged, wound-like perforations in Burri’s burlap sacks act on the viewer in much the same way that the open neckline in Untitled (ca. 1955) does, evoking a visceral feeling of direct physical identification, the holes on the surface of Burri’s canvases peel back like burst blisters to reveal the layers underneath. He transforms his materials, thus estranging them from their real-life sources, whereas Rauschenberg steadfastly retains enough of each found item’s inherent characteristics to invoke its original context and associations, in this case the personal and bodily implications of a shirt.

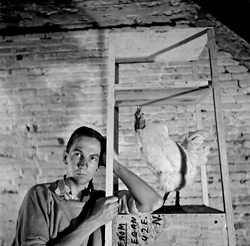

6. Attributed to Robert Rauschenberg, cropped contact sheet showing Untitled [self-portrait with Odalisk (1955/1958), early state, Fulton Street studio], ca. 1954, printed ca. 1980; Robert Rauschenberg Foundation; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Graham Bader has argued convincingly for an understanding of the Combines as a form of surrogate through which Rauschenberg explored the body both as corporeal reality and as carrier of constructed meaning. Bader centers his argument on Rauschenberg’s use of clothing fragments, noting that in our clothes, “we most directly experience our bodies’ negotiation between carnal and semiotic registers.”11 For Bader, the shirt in Untitled (ca. 1955) enacts confrontations between “volume and surface, body and sign, presence and absence.”12 This reading sees Rauschenberg referencing the body in the abstract and using clothes to index people as readable signs that are equivalent to the other everyday items incorporated in the artist’s works. But the shirt in Untitled (ca. 1955) also can be understood as a surrogate for and a more direct allusion to the artist himself. Sweatshirts are comfort clothes, often referred to as second skins. Sweatshirts were also a kind of uniform for Rauschenberg, something he would wear on an average studio workday in the mid-1950s (fig. 6). Many authors have discussed Rauschenberg’s intense physical relationship with his materials, as did the artist.13 With reference to his earliest efforts at painting, he stated, “At the time I found it too distant to even use a brush. I needed the immediate contact. If I could have been the canvas too, that wouldn’t have been close enough for me.”14 With Untitled (ca. 1955), it is as if Rauschenberg literally entered the picture and left behind his shirt, embedded in the surface of the work like forensic evidence or a molted skin. Yet this gesture should not be confused with Abstract Expressionism’s emphasis on the direct transmission of the artist’s psyche through his or her hand onto the painted surface, an ideal Rauschenberg frequently disclaimed.15 Perhaps Untitled (ca. 1955) also comments dubiously on this idea of a permeable boundary between self and art and the aim of leaving one’s soul on the canvas. As such, this melancholy and restrained work represents an unusual, self-reflective pause in—or even a detour from—the mainline development of the Combines, as though Rauschenberg lingered for a moment to ponder the complicated bond between painter and painting.

Notes

- A note about the date of this work: As will be discussed in greater depth later in the essay, the technique used to apply the layer of paint on the surface of the work is similar to that used in the artist’s Red Paintings and Black paintings, suggesting a date of 1955, a relatively early point in the development of the Combines. However, a newspaper clipping visible on the work’s surface (which will also be discussed further) points to a spring flood. There was major flooding in Connecticut and New York in March 1956, which would have been reported in newspapers available to Rauschenberg. There were no major spring floods in New York or New England in 1955; this may suggest that the work was not completed until after spring 1956.

- Yve-Alain Bois discusses Rauschenberg’s efforts to collapse the distinction between canvas/surface and support in “Eye to the Ground,” Artforum 44, no. 7 (March 2006): 248, 317.

- Records in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, indicate that the work was considered by curator Dorothy Miller for inclusion in the exhibition Sixteen Americans (December 16, 1959–February 17, 1960), but was ultimately ruled out. Dorothy C. Miller Papers, I.15.1, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Although it is possible that Leo Castelli showed the work in Rauschenberg’s solo exhibitions of 1958 or 1960, or in a group show in the same time frame, this seems unlikely because of the artist’s and Castelli’s strong emphasis on showing only the most recent work. Extant checklists and exhibition photographs, though not comprehensive, do not include this work.

- The exact dates of the loss and recovery are unknown. A slide of the work without the funnel appears to be dated 1970. The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation’s file for this artwork indicates that it was cleaned and restored in January 1984, which is likely when the funnel was reattached.

- The Foundation’s file for this artwork contains a handwritten note detailing inquiries to pursue, among them, “Should hole in center of sweatshirt be repaired?” The reply: “Bob ignored this question.”

- The underlying painting has not been identified. One large-scale Red Painting shown in the Charles Egan Gallery exhibition of 1954–55 is known to have been divided into multiple smaller canvases that were then painted over, but the resulting smaller works have not been identified definitively. See references in December 1954 and January 1956 to Untitled [red Combine painting] (1954) in Joan Young with Susan Davidson, “Chronology,” in Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective, ed. Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 554, 555.

- Many of Rauschenberg’s 1954–55 works that straddle the transition from the Red Paintings to the Combines are untitled. After 1955, the artist increasingly gave titles to his works upon their completion. While preparing for the 1976 retrospective organized by Walter Hopps for the National Collection of Fine Art (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum), Rauschenberg retroactively titled some of his major Combines, including Collection (1954/1955), though many smaller-scale Combines remained untitled.

- See Levee (1955); Untitled (ca. 1955, Stefan T. Edlis Collection); Interior (1956); and Honeysuckle (1956).

- The shirt in Charlene is framed in a neat rectangle with the uncut neckline flattened at top and center. In Double Feature the shirt is cut off at mid-torso and missing a sleeve, but the neckline again is whole and laid flat. Door includes a whole undershirt, again flat. All of these neck holes are completely closed and inaccessible. It should be noted that photographs of Charlene in its early state show a different configuration, without the T-shirt. Charlene appears to have been reworked in the late 1950s or early 1960s, perhaps just in advance of its being shown in 4 Amerikanare: Jasper Johns, Alfred Leslie, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Stankiewicz, which traveled Europe in 1962, or before being sold to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1965. See the image published in Walter Hopps, ed., Robert Rauschenberg (Washington, D.C.: National Collection of Fine Arts, 1976), 78.

- Rauschenberg met Burri in Italy in 1953 after the Sacchi were well underway, and Burri arranged for Rauschenberg to have an exhibition at Galleria dell’Obelisco, Rome, in March 1953. Burri had two solo exhibitions at the Stable Gallery, New York, one in 1953, the other in 1955. He also received attention for his inclusion in Younger European Painters at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 1953. The two artists clearly knew each other’s work, and the matter of their mutual influence is complicated. See Germano Celant, “Alberto Burri and Material,” in Alberto Burri (New York: Mitchell-Innes and Nash, 2007), 9–12.

- Graham Bader, “Rauschenberg’s Skin,” Grey Room 27 (Spring 2007): 106. Bader also associates this piece with the early 1960s sculptures of Lee Bontecou (b. 1931) and contrasts Bontecou’s aggressively suggestive interiority to the insistence on surface in Untitled (ca. 1955). See page 118n16.

- Ibid., 110.

- The earliest comment on the physical identification between Rauschenberg and his materials occurs in Frank O’Hara’s review of Rauschenberg’s 1954–55 exhibition at Charles Egan Gallery: “He provides a means by which you, as well as he, can get ‘in’ the painting.” Frank O’Hara, “Reviews and Previews: Bob Rauschenberg,” ARTnews 53, no. 9 (January 1955): 47. Lawrence Alloway notes Rauschenberg’s “lyrical ergonomics” and sensitivity to the correlation of his materials to human scale. Lawrence Alloway, “Rauschenberg’s Development,” in Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg, 11.

- John Gruen, “Robert Rauschenberg: An Audience of One,” ARTnews 76, no. 2 (February 1977): 46.

- See discussion throughout Robert Rauschenberg, Oral History Interview conducted by Dorothy Gees Seckler, December 21, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., accessed August 16, 2012, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-robert-rauschenberg-12870/. See also Barbara Rose, An Interview with Robert Rauschenberg (New York: Vintage Books, 1987), 50–51; and Calvin Tomkins, Off the Wall: Robert Rauschenberg and the Art World of Our Time (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980), 88–90.