In 1991, Robert Rauschenberg began to exploit a new method of incorporating photographic images into his paintings, abandoning both the silkscreen printing process he had been using for three decades and the transfer drawing technique involving chemical solvents that he had employed for almost four. The new process made use of state-of-the-art technologies and was in line with his interest in merging art and technology as well as his environmental concerns. From this point on, Rauschenberg worked with digitized images generated from a copious stash of slides and photographs that he printed on transparent sheets using soy-based and other water-soluble inks and dyes. Employing water-soluble media meant that water (rather than chemicals) could be used to release the images onto the paper surface when the prints were burnished from the back during the transfer process.

In the first series Rauschenberg produced in this manner, Waterworks (1992–95), each piece features a limited number of images (generally no more than three or four) organized in strict rectilinear fashion (fig. 2). The artist employed a mechanical press similar to the kind used in lithography to transfer these evenly toned, high-resolution images. By the time he began the Anagram series (1995–97) he had mastered this process, and his manner of working became more characteristically improvisational. In these later works a greater number of images are dispersed across larger sheets of paper, their transfer by hand or through the action of a small, hand-held scraper resulting in an overall gestural appearance. Throughout the Anagrams works, the images and image fragments have been deposited upon the surface of the paper in a way that more fully exploits the fluid nature of the water-based media. In the series that followed—Anagrams (A Pun) (1997–2002), of which Port of Entry (1998) is a part—polylaminate, a surface made of layers of laminated paper mounted on aluminum, has replaced paper as the works’ support.

Port of Entry consists of three vertically adjoined polylaminate panels covered with an energetic display of both high-color and black-and-white imagery. Rauschenberg selected the images seen in this work and others from this period from among hundreds of his photographs, which assistants in his studio on Captiva Island, Florida, printed on transparent sheets, ensuring that they had on hand multiples of each image as well as alternate versions in different sizes and scales (fig. 3). The printouts were set on tables in large stacks, and Rauschenberg would select those he wanted to use; several paintings within series and many paintings belonging to different series feature the same images, although in varying juxtapositions. Certain images in Port of Entry were used only once, such as the graphic rendering of the tiger’s head and the photographic image of elephants seen from the rear that adjoin along the work’s left edge, while others repeat or echo throughout the composition. The photographic image of a three-dimensional ice cream cone (probably from a shop sign), for example, is repeated vertically in the same size. In a nearby image are two women in saris whose forms and colors (one is red-and-white striped and the other pink) play wittily against those of the ice cream cones, their contours repeated three times in two different sizes (the woman in pink cropped from the image in the slightly larger version). Above and to the left of the ice cream cones is a street sign with a paint red border that encloses the silhouette of a walking man. The sign’s flat, medallion-like form is reproduced at different scales both in whole and in part, appearing large and intact near the painting’s upper left corner, as a tiny element in a construction scene (where it is flipped in the opposite direction) near the painting’s center, and also as a fragment (only a small portion of the red rim visible) at the bottom right. The cluster of yellow, plastic-coated pipes coming out of the ground in the construction image also appears larger and in reverse along the painting’s right edge. Close examination reveals additional repetitions and reversals.

Some of the images in Port of Entry declare themselves as specifically American, such as the fragment of the red fire truck emblazoned with the letters “NY” near the painting’s top center and the still-life scene at the bottom edge, which includes an American flag and two framed prints of great masted ships. The work’s title points to the place one enters a new country, an allusion that the reference to New York and the image of the ships would seem to reinforce. Here, however, the artist’s frame of reference extends beyond America, as the work includes photographs taken by Rauschenberg during his international travels. Rauschenberg can unquestionably be described as having been “a man of the world.” Although born and raised in Port Arthur, Texas, he rapidly expanded his horizons once he decided to become an artist, making his way to New York and then to Paris to study. He embarked on numerous international journeys, including a trip in 1952 with his friend Cy Twombly through Italy and North Africa and a six-month world tour he made in 1964 as lighting, set, and costume designer and stage manager for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. (During this time he also staged performances of his own, and won the International Grand Prize in Painting at the Venice Biennale.) Travel continued to be a mainstay of his existence, and in the decades that followed he participated in exhibitions and collaborated with artists and artisans around the world. The ROCI (Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange) project of 1984–91 marked the culmination of his international interests. As part of this largely self-financed initiative, Rauschenberg arranged a touring exhibition of his work that traveled to numerous politically sensitive countries, including Mexico, Chile, Venezuela, China, Tibet, Japan, Cuba, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, East Germany, and Malaysia, before ending its tour at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.1 In preparation for each presentation he met with local politicians as well as with poets, writers, and journalists, who contributed to the unique exhibition catalogues produced for each venue. He also worked with local artists and artisans, using native materials, processes, and imagery to create new pieces for each exhibition and taking photographs of what he saw and experienced. As a self-appointed cultural ambassador the artist aimed to promote world peace and understanding and to break down barriers at a moment when the globalization of today’s art world was still unimaginable. This diplomatic mission was, moreover, an extension of Rauschenberg’s long-standing engagement with political and social issues and philanthropic endeavors,2 among them his founding of Change, Inc., in 1970 to help artists in need of emergency funds; his support of artists’ rights, nuclear disarmament, and anti-apartheid movements; and his participation in various international conferences hosted by the United Nations.

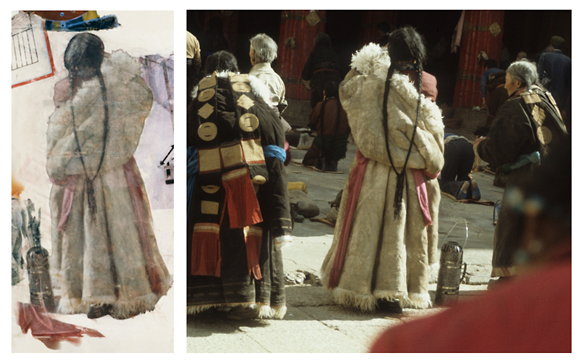

In addition to the images of international origin in Port of Entry mentioned above, the work includes a picture of a pigtailed woman seen from the back (fig. 4) that was taken by the artist in Tibet;3 an image of a statue of a man holding a ladder, identified as one of forty-eight bronze figures in a park at Place du Petit Sablon in Brussels, Belgium, that commemorate the arts and crafts guilds of Brussels;4 and a very faint image consisting of a row of white squares, repeated twice in the composition, which is derived from a photograph of linens on a clothesline that was taken by the artist in Cuba (more legible versions of the scene are found in several of his ROCI Cuba paintings).5

While the title of the series to which Port of Entry belongs, Anagrams (A Pun), suggests wordplay (in an anagram, the letters of a word are rearranged to produce a new word), Rauschenberg seems to have used it, much as he did the title Rebus in 1955, to suggest that his work be viewed as a kind of picture puzzle, one in which images collide and play against one another in the viewer’s eye and mind. In Port of Entry, for example, the diagonal stripes of the sari repeat those of the American flag; the fat silver pipe at lower right suggests the trunks of the elephants exiting the canvas near the bottom left; and the stance of the statue of the man with the ladder echoes the silhouette of the walking man, while offering the contrast of seemingly static and active figures. Thus while the title Port of Entry seems to refer in a fairly literal way to the phenomenon of international travel, it also invites the viewer to embark on a metaphorical journey into a universe of collaged fragments that can be reassembled at will within his or her mind.

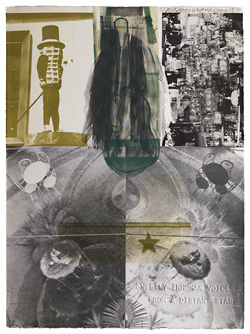

Although such openness to interpretation is pervasive in Rauschenberg’s art, the use of the title Port of Entry for this work of 1998 may be a pointed reference to his friend and one-time collaborator William S. Burroughs (1914–1997), a noted Beat poet who had died the year before.6 In 1996, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art mounted a large-scale exhibition of art and literature entitled Ports of Entry: William S. Burroughs and the Arts.7 This exhibition paid homage to Burroughs, whose best-known book, the controversial Naked Lunch (1959), initiated his move to a nonlinear narrative style that was said to reflect the fragmentation of society and experience, constituting a literary equivalent of sorts to Rauschenberg’s contemporary Combines (1953–64). It was also in 1959 that Burroughs made what he called a “port of entry” into the visual arts and began to use cut-up texts, photographs, and found images to construct “scrapbook” collages.8 In 1972 Rauschenberg executed an offset lithographic poster, Dream of William Burroughs, an ecologically themed collage that incorporated a Burroughs quote,9 and in 1981 Rauschenberg and Burroughs collaborated on American Pewter with Burroughs I−VI, a portfolio of lithographs reflecting on American life and imagery that was produced at Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, and featured images by Rauschenberg and embossed texts by Burroughs. (One of these lithographs was included in the LACMA show. See fig. 5.)

Port of Entry, then, is a complex, multifaceted work that operates on any number of levels—as a record of Rauschenberg’s travels, an homage to Burroughs, and a composition filled with visual play as well as memory and experience. Brought into being both by contemporary technologies and through the action of the artist’s hand, it stands as a testament to Rauschenberg’s enthusiasm for exploration and experimentation and his engagement with the world.

Notes

- For more on ROCI, see Jack Cowart, ed., Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (Washington, D.C: National Gallery of Art, 1991).

- Established in 1990, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation is a nonprofit entity devoted to projects that increase public awareness of subjects of vital importance to the artist: medical research, education, the environment, homelessness, world hunger, and global enhancement of the arts. Since Rauschenberg’s death the Foundation has remained focused on promoting the artist’s values and his stated philosophy: “Art can change the world.”

- The identification of this figure derives from a note in the artist’s studio file. The image of the pigtailed woman is also seen in Tribute (Anagram) (1995) and Second Story [Anagrams (A Pun)] (1998). Rauschenberg was in Tibet with ROCI in 1986, during which time he created the series Tibetan Keys and Tibetan Locks (both 1987). In 1996 he created prints and posters to benefit the people of Tibet through the organization Future Generations.

- Sarah Roberts, Andrew W. Mellon Associate Curator of Painting and Sculpture at SFMOMA, identified the statue. For contemporary views and information, see “Place du Petit Sablon,” Brusselspictures.com, https://www.brusselspictures.com/2008/01/17/place-du-petit-sablon and “Brussels: Small Sablon Square,” Europe-Cities.com, www.europe-cities.com/en/786/belgium/brussels/place/24474_small_sablon_square/. Rauschenberg likely made several visits to Brussels, so it is difficult to pinpoint the date the sculpture was photographed.

- All of the ROCI Cuba works are dated 1988, and the ROCI Cuba presentation was held at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Castillo de la Fuerza and Casa de las Américas, Galleria Haydee Santa Maria, Havana, from February 10 to April 3, 1988, so the Cuba photographs were likely taken the previous year.

- Burroughs died on August 2, 1997. That Rauschenberg did not execute a work in homage to Burroughs until 1998 may perhaps be due to the fact that he was occupied by preparations for a monumental traveling retrospective organized by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum that opened in New York on September 19, 1997.

- Robert A. Sobieszek, Ports of Entry: William S. Burroughs and the Arts (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1996).

- For a discussion of the origins of Burroughs’s “cut-ups” and the influential role played by his friend the British-Canadian artist Brion Gysin (1916–1986), see Sobieszek, Ports of Entry, 18−20.

- Robert S. Mattison, Last Turn–Your Turn: Robert Rauschenberg and the Environmental Crisis (New York: Jacobson Howard Gallery, 2008), 11–12.