Sleep for Yvonne Rainer is one of three related works from 1965 that connect to Robert Rauschenberg’s involvement with dance and performance, particularly in the context of Judson Dance Theater. Each celebrates a friend with whom the artist had developed a rich artistic exchange or collaboration in the early 1960s—in this instance the dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer (b. 1934), whose significance to Rauschenberg’s practice will be discussed in greater depth below. The other two works recognize Öyvind Fahlström (1928–1976) and Robert Morris (b. 1931), respectively.1 All three works feature movable elements that allow for variable compositions, an idea that dates to the artist’s Elemental Sculptures of 1953. In each of them we also find Rauschenberg weaving together changeable compositions, imagery from his recently completed silkscreen paintings, and objects attached to the surface, in the mode of his Combines (1953–64).

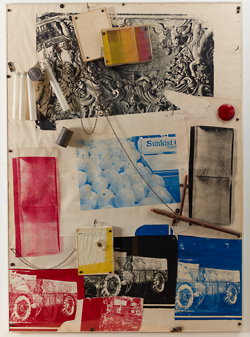

Sleep for Yvonne Rainer’s primary support is linen over a wooden stretcher. Attached to that surface are eight silkscreened images—four pictures of an army truck, a crate of Sunkist oranges, a detail of an architectural fragment, and two pictures of a pair of pillows. The images are screened on cut or torn pieces of paper that were stapled and perhaps also glued to the linen. Joined sheets of Plexiglas attached with screws cover the whole surface and its edges, separating the inner layer of silkscreened imagery from an outer layer of assemblage elements. At the upper left, four empty caulking tubes are strung together on a bent wire, the ends of which are anchored through the Plexiglas surface. Between the third and fourth tubes, a tin can, crushed at one end, is also connected to the wire. Slightly below the tubes is another tin can, which is movable; although shown here at a thirty-degree angle, the can swivels and has been photographed in multiple positions. On the far right, a red plastic taillight is screwed to the surface. Below the taillight, fragments of chair rungs are secured with metal straps. At the bottom right corner, a small tube of paint is fastened atop the Plexiglas sheet.

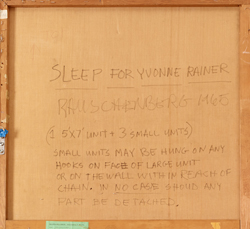

The composition also includes three small movable panels, each measuring roughly nine by twelve inches. The panels are connected by thin chains of different lengths attached to open-eye bolts. Hooks at the top of the panels allow them to be hung in various configurations from right-angle hooks on the work’s surface (fig. 2). The first part of Rauschenberg’s inscription on the verso of the work (fig. 3) itemizes these units and emphasizes their mobility, which he considered a key feature of this piece: “(1 5′ X 7′ UNIT + 3 SMALL UNITS) / SMALL UNITS MAY BE HUNG ON ANY / HOOKS ON FACE OF LARGE UNIT / OR ON THE WALL WITHIN REACH OF / CHAIN.” Rauschenberg often lamented the stasis of visual art and sought ways to incorporate movement and change in his artworks. He once noted, “I’ve always attempted to bring art into real time—where it will change because of someone’s presence.”2 Accordingly, Sleep for Yvonne Rainer occupies the traditional two-dimensional space of painting but is also performative; the viewer is invited to “choreograph” the work by arranging the movable elements.

Shortly before completing Sleep for Yvonne Rainer, Rauschenberg had become deeply engaged in dance and performance through contact with a group of young choreographers he met at dance composition classes taught by Robert Dunn (1928–1996) at Merce Cunningham’s studio between 1960 and 1962. That group became the core of the aforementioned Judson Dance Theater, an informal assembly of experimental dancers and choreographers (many of whom were also active in other artistic disciplines) that performed at the Judson Memorial Church in New York’s Greenwich Village between 1962 and 1964. Judson’s performances radically challenged the conventions of modern dance, and a number of the individuals involved—including Rainer, Trisha Brown (b. 1936), Lucinda Childs (b. 1940), Simone Forti (b. 1935), Meredith Monk (b. 1942), and La Monte Young (b. 1935)—became highly regarded choreographers and performance artists.

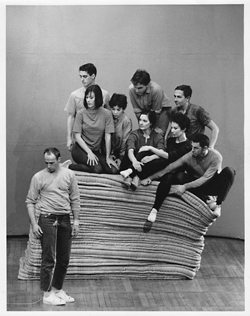

4. Production photo of Yvonne Rainer's Parts of Some Sextets, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, March 6, 1965. Pictured performers: Robert Morris, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer (front left on mattresses), Deborah Hay, Tony Holder, Sally Gross, Robert Rauschenberg (back right on mattresses), Judith Dunn, and Joseph Schlichter. Photo: Peter Moore © Barbara Moore / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Among the young choreographer/dancers Rauschenberg encountered, it was Rainer who would become his most significant collaborator at this time. Rainer first became aware of Rauschenberg’s art at his 1958 Leo Castelli Gallery exhibition. She recalls, “That show opened up a new world for me—of irreverent play and challenge.”3 Rainer further remembers that she saw “quite a bit” of Rauschenberg at the Dunn classes.4 In 1963, Rauschenberg designed the lighting for Rainer’s dance Terrain. That same year, he began to choreograph his own performance works, beginning with Pelican (1963) and later Elgin Tie (1964) and Spring Training (1965). In 1965, he participated in Rainer’s We Shall Run (¾) and Parts of Some Sextets (fig. 4) and designed the lighting for the three-evening performance Yvonne Rainer and Robert Morris with Judson Dance Theater. Rauschenberg’s challenging use of everyday objects in his visual art profoundly affected Rainer, and he in turn was deeply interested in the Judson dancers’ engagement of common movements and tasks. Rainer has written that in contrast to the “overblown plot” of traditional dance, “The alternatives that were explored are obvious: stand, walk, run, eat, carry bricks, show movies, or move or be moved by some thing other than oneself.”5 Rainer’s emphasis on dances that are constructed from everyday activities reinforced Rauschenberg’s interest in motion, both actual and suggested, in his art. The connections are particularly clear in Sleep for Yvonne Rainer, whose title is probably derived from the “Sleep Solo” in Rainer’s Terrain, a suggestion with which Rainer concurs.6 That solo consists of a dancer removing everyday objects from a bag and clutching them to her/his body “while simulating sleep.”7 Rauschenberg certainly felt Rainer’s affinity for the use of common objects in Terrain, and he may have viewed sleep as one of the most radical types of dance movements.

The imagery in Sleep for Yvonne Rainer depicts various types of motion as well as stasis. The repetition of four lithographs of an army truck, each of them slightly different from the last, makes the vehicle appear to charge aggressively through the lower part of the work. In contrast, the Sunkist oranges at the center of the composition seem to tumble toward us in chaotic disorder. At the top of the work, upside-down putti dance amid a profusion of baroque ornament. The angled line of caulking tubes has its regular march disrupted by the intrusion of the tin can. The silkscreened images of the truck, oranges, and architectural ornament appear in different contexts in other Rauschenberg works.8 The two images of a pair of pillows, one red and the other black and white, seem to be exclusive to this piece, and they connect not only to the title but also to Rainer’s use of actual pillows in her dances.9 As a whole, these silkscreened images provided a vocabulary that the artist could employ from artwork to artwork in differing syntactic arrangements to suggest a variety of associations. The fact that Rauschenberg saved paper proofs from his silkscreen paintings—he ordered the original screens to be destroyed in 196410—and repurposed those proofs in Sleep for Yvonne Rainer and the two related works for Fahlström and Morris highlights his use of the imagery as a flexible vocabulary.11

Critical writings on Rauschenberg range from attempts to establish a detailed iconography in individual works to assertions that his particular choices of objects and images are random and should not be overinterpreted.12 To this writer, it seems clear that there are links in the artist’s choice of iconography and materials.13 At the same time, however, his works do not lend themselves to a strict iconographic interpretation. Having studied Rauschenberg’s oeuvre, and having seen him work in the studio on three occasions, my view is that his artistic choices form chains of associations, connections that are made intuitively during the creative process and that often revolve around a central theme.14 Rauschenberg’s themes are not metaphors for feelings but linkages between physical events, activities extended into materials.

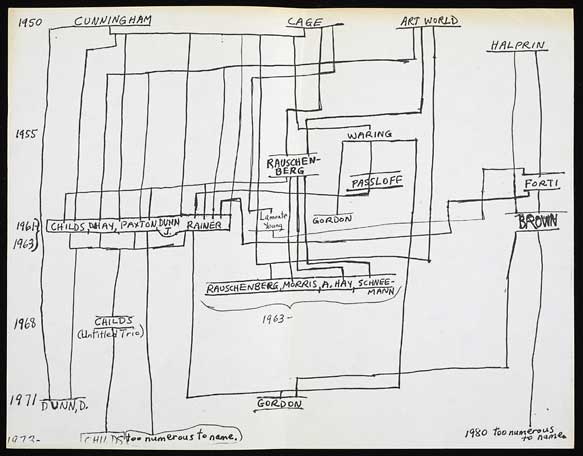

5. Diagram of artistic influences created by Yvonne Rainer in response to a July 1980 New Yorker article about the avant-garde dance community. Yvonne Rainer papers, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2006.M.24)

This idea of linkage is particularly clear in Sleep for Yvonne Rainer, which includes multiple movable items connected by chains. Significantly, the possibility of multiple configurations explores both motion and stasis while also underscoring the mutability of such chains of association. In 1980, Rainer made a diagram (fig. 5) resembling a choreographic plan that captures the creative interconnectivity of the 1960s, when her key collaborations with Rauschenberg were executed.15 It is noteworthy that Rainer placed Rauschenberg near the center of the web of artists. Ultimately Sleep for Yvonne Rainer, like this diagram, embodies the complex artistic linkages that fascinated both individuals and characterized an era in which a widely varied, multidisciplinary group of artists came together and productively blurred traditional lines between art and performance.

Notes

- Fahlström, a Swedish multimedia artist, is recognized in N.Y. Bird Calls for Öyvind Fahlström (1965, private collection). His A Lecture on Birds in Sweden was excerpted by Rauschenberg to create an eleven-minute score that accompanied the performance work Shot Put (1964). Morris, an American sculptor and conceptual and performance artist who in the mid-1960s was actively involved in Judson Dance Theater, is honored in Fossil for Bob Morris (1965, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.). Sleep for Yvonne Rainer, N.Y. Bird Calls for Öyvind Fahlström, and Fossil for Bob Morris all feature movable items connected by chains. The dedication of these works to individuals connects them with Rauschenberg’s trophies of the early 1960s, such as Trophy II (for Teeny and Marcel Duchamp), Trophy IV (for John Cage), and Trophy V (for Jasper Johns).

- Robert Rauschenberg quoted in Richard Kostelanetz, The Theatre of Mixed-Means: An Introduction to Happenings, Kinetic Environments, and Other Mixed-Means Presentations (New York: Dial Press, 1968), 94. Among Rauschenberg’s numerous experiments with this idea are Interview (1955, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), with its door that pivots to expose or conceal parts of the work, and Black Market (1961, Museum Ludwig, Cologne), which was initially conceived as a selection of various objects that could randomly be added to or removed by viewers.

- Yvonne Rainer, email to the author, February 19, 2013.

- Ibid.

- Yvonne Rainer, Work 1961–73 (Halifax: Press of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974), 66.

- Yvonne Rainer, email to the author, February 20, 2013.

- Rainer, Work 1961–73, 21.

- For instance, the Sunkist oranges appear in Windward (1963), Harbor (1964) and Stunt (1965); the trucks are featured in Crocus (1962), Barge (1962–63), and Retroactive II (1964); and the architectural detail is found in Manuscript (1963), Overdraw (1963), and Shaftway (1963).

- Although Rainer cannot recall if there were pillows in “Sleep Solo,” she has provided an extensive list of her works in which pillows were used. Rainer, email to the author, February 20, 2013. Rainer also used the movement of gym mattresses as a primary device in Parts of Some Sextets (1965). Possibly, the two pillows in the lithograph refer to Rainer and Robert Morris.

- See Joan Young with Susan Davidson, “Chronology,” in Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective, ed. Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 564.

- For further analysis of Rauschenberg’s silkscreen paintings, see the discussion of Barge (1962–63) in Susan Davidson, “Robert Rauschenberg,” in Guggenheim Museum Bilbao Collection (Bilbao: Guggenheim Bilbao, 2009), 90–97.

- See Charles F. Stuckey, “Reading Rauschenberg,” Art in America 65, no. 2 (March–April 1977), 74–84, and Branden W. Joseph, Random Order: Robert Rauschenberg and the Neo-Avant-Garde (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 166.

- An obvious example close to our examination is N.Y. Bird Calls for Öyvind Fahlström, discussed in note 1 above, which references a performance by Fahlström that was accompanied by the artist’s birdcalls. Rauschenberg’s artwork features at least ten images of birds.

- See chapter 1 in Robert Saltonstall Mattison, Robert Rauschenberg: Breaking Boundaries (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), and R. F. Jarrett and Karl E. Scheibe, “Association Chains and Paired-Associate Learning,” Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 1, no. 4 (January 1963), 264–68.

- Rainer created the diagram in response to Arlene Croce, “Dancing: Slowly Then the History of Them Comes Out,” New Yorker, June 30, 1980, 92–95.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette College, Easton, PA

Photo courtesy of Lafayette College, Easton, PA