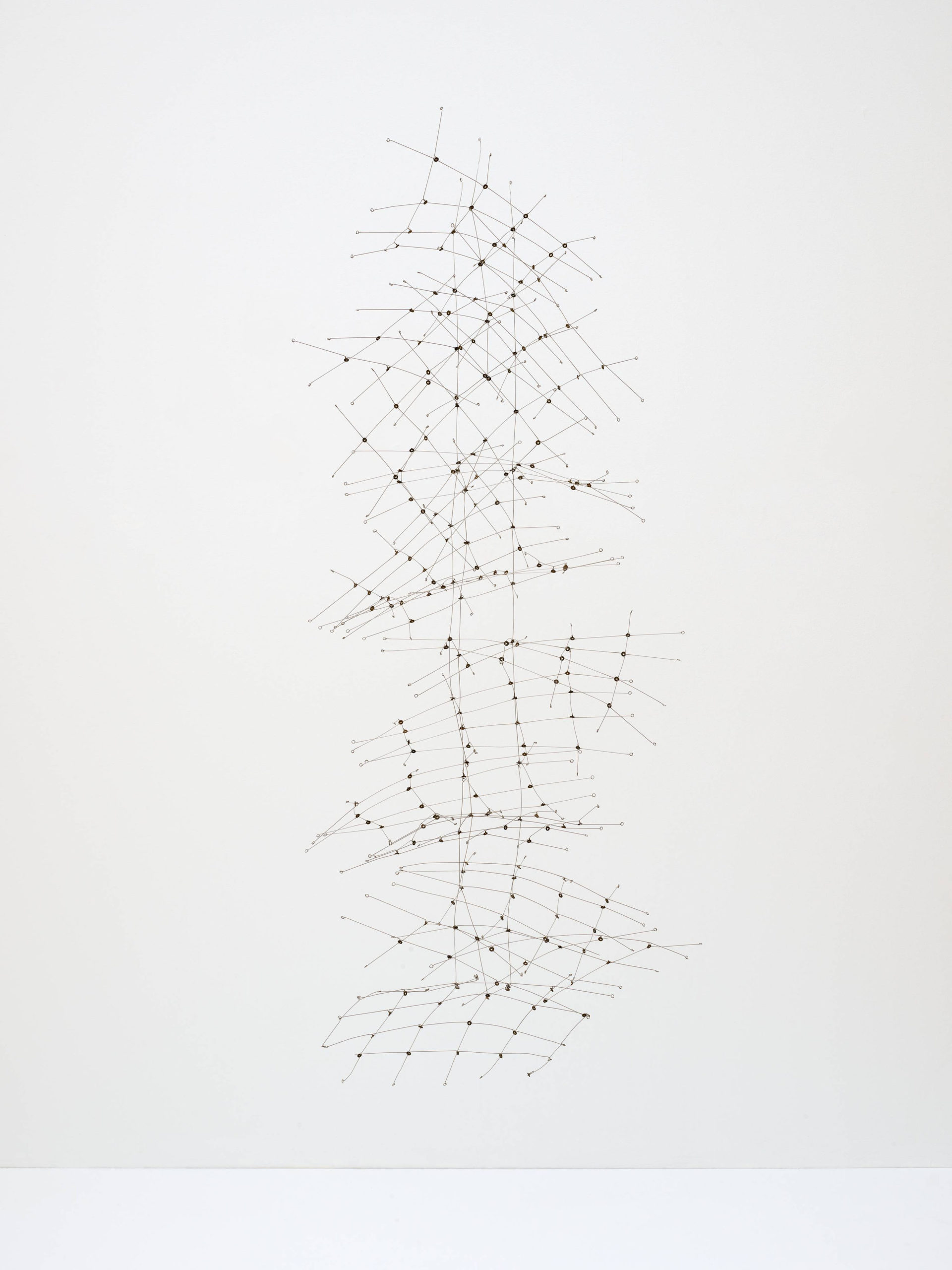

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), Columna (Column) 7l/9, 1971; stainless steel rods and iron washers; 79 ½ × 27 ½ × 27 ½ in. (201.9 × 69.9 × 69.9 cm); Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions, 2018; © Fundación Gego

Trained as an architect, the artist known as Gego used thin metal wires to map the invisible fields we inhabit. “I use the lines,” she said, “to define spaces, to define space itself.”1 In Column 7l/9 (1971), wires and small washers form crisp crosshatched planes, while bends in the filament introduce sinuous distortions. The sculpture articulates an unusual understanding of space—one where precise geometry meets incidental mutation. By tracing the evolution of Gego’s thoughts on architecture and the urban environment from the 1930s on, we can see how this conception reconciles the rigid systems of modernist design with the elastic, unpredictable flows of everyday life.

Gego was born Gertrud Goldschmidt in Hamburg in 1912 and grew up during the emergence of the Bauhaus, an influential German school where architects and designers forged geometric principles of construction. Many of those associated with the Bauhaus believed that the rational organization of space would inaugurate a new era of efficient and equitable living on a universal scale. Inspired by the “novel concept of construction as a social proposition” that emerged from this new architectural discourse, Gego enrolled in the Technische Hoschschule Stuttgart (Stuttgart Technical School, now University of Stuttgart) and graduated in 1938 with a degree in architecture.2 The crisp lattices of Column 7l/9 could easily belong to an architectural model, and their even units recall the proportional forms of much Bauhaus design

Gego remained doubtful, however, that rational planning could align with lived experience. Her mentor in Stuttgart, Paul Bonatz, famously reacted against the geometric structures of the Bauhaus and their global application, instead promoting traditional architecture that emerged from local customs. For Gego, as for Bonatz, modernist architecture threatened to impose generic forms on culturally specific ways of life.

This problem crystallized for the artist when, in 1939, she was forced to flee Nazi Germany and emigrate to Caracas, Venezuela. There, Gego witnessed an explosion of rational planning under General Marcos Pérez Jiménez’s Plano Regulador, which divided Caracas into zones, cut large boulevards through the city, and imposed a grid of streets and skyscrapers. Privileging clear sightlines and orderly arrangements, the initiative intended to bring modernity into the city. Ultimately, however, the Plano Regulador buckled under its geometry. The separation of commercial and residential areas made daily tasks difficult for the city’s residents, and crime skyrocketed in areas with insufficient foot traffic. The program was blind to the ways in which inhabitants wind through urban space along unstructured paths that meet their personal needs.

In Column 7l/9, Gego remedies this disconnect by fusing the geometric and the incidental. Working without sketches or models, she shaped her latticed planes by hand, bending and twisting wire to achieve a precarious symmetry. Each gridded layer sits on a different axis, such that every view of the sculpture offers a new set of intersections, encouraging us to wander around the work, much the way one wanders through a city. Three vertical wires that hold the lattice structures together curve unevenly in order to maintain a centripetal balance, exemplifying the interplay of structural logic and improvised alteration. In this work, Gego opened up the grid to contingency, multiplicity, and fortuitous realignment.

Similar structures emerged in the shantytowns surrounding Caracas. Inhabitants built their own homes in zigzagging arrangements along the city’s ridges, contorting the order of the Plano Regulador into new formations that camber, curve, and face in every direction. Whether or not Gego took inspiration from these shantytowns, Column 7l/9 parallels their informal approach to planning—one where the rational and the instinctual, the universal and the particular, become intertwined.

Notes

- María Luz Cárdenas, “A Conversation with Gego,” in Nadja Rottner and Peter Weibel, eds., Gego, 1957–1988: Thinking the Line (Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2006), 225.

- Gego quoted in Hannah Feldman, “Chronology,” in Rottner and Weibel, Gego, 1957–1988, 96.