1. Portrait of Grace McCann Morley taken by Brett Weston, ca. 1945. SFMOMA Archives

The San Francisco Museum of Art (SFMA) did not add the word modern to its name until 1976 but it was a modern museum from the very start. This is due in large part to the extraordinary efforts of its first director, Grace McCann Morley (fig. 1). A determined supporter of avant-garde art and artists, Morley also believed passionately in cultural democracy—that art should be available to everyone—and held firm convictions about the crucial role that museums could play in this endeavor: “If art of today is today overlooked, or misunderstood, the loss is serious. Art fails, then, to give its full value to daily life. . . . The first responsibility of museums of contemporary art is to help as broad and as large a public as possible to understand, appreciate, and use art of its own time.”1 When it opened in January 1935, SFMA was the only museum on the West Coast, and one of very few in the country, dedicated to modern art. But Morley’s museum was also modern in that it eschewed the traditional nineteenth-century emphasis on collecting, preserving, and “passive” educational methods in favor of a focus on public outreach and interactive learning.2

Morley’s populist strategy informed many aspects of her twenty-four-year career at the museum; it is particularly evident in the exhibitions and educational programming she initiated during its early years. Morley faced significant financial, geographic, and philosophical challenges, especially as a woman working outside the East Coast art establishment. She overcame these obstacles by deploying her formidable intelligence, considerable savvy, and a lot of old-fashioned elbow grease. Her accomplishments are little known, yet she played a singular role in establishing San Francisco as a thriving center for artists, collectors, and museumgoers interested in supporting the very latest developments in avant-garde art, the effects of which are still felt today. Her efforts to bring diversity, outreach, and experiential learning to the museum, highly progressive for her time, anticipate the preoccupations of current museum administrators.

Morley was a perfect fit for the San Francisco job: a California native with impressive academic credentials, international exposure to modern art, and firsthand experience in state-of-the-art museum practice. She studied French literature at the University of California, Berkeley, and then traveled abroad to earn a PhD in French literature and art at the Sorbonne. It was in Paris that Morley received her first comprehensive exposure to modern art, attending exhibitions of the work of Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Raoul Dufy, artists she would later champion in San Francisco. After finishing her degree Morley took a job teaching French language and literature at Goucher College in Baltimore but was soon recruited to take on art history as well. For training she was sent to a summer course for art professionals at Harvard,3 and soon thereafter she was hired as a curator at the Cincinnati Art Museum. She returned to the Bay Area in 1933 and a year and a half later was hired to direct the fledgling San Francisco Museum of Art, only months before it was set to open. Morley quickly assembled a small staff and got down to work.

The inaugural shows were an eclectic array, a result of the compressed time frame and meager resources: the fifty-fifth Annual of the San Francisco Art Association (SFAA), French prints, gothic and renaissance tapestries, ancient Chinese sculptures, and modern French paintings. To some extent the schedule was dictated by what was available to show, but Morley was also quite deliberate in her effort to balance the program to appease the more conservative trustees and critical members of the public who were not prepared for a steady diet of new art. Even progressive trustees, those who were sympathetic to what Morley called her “modern tendencies,” needed slow nurturing and guidance. Equally important was the strategic inclusion of work by local artists, many of whom as members of SFAA had played a major role in establishing the museum and had a vested interest in its activities. During Morley’s tenure, roughly one-third of the museum’s gallery space was dedicated to Bay Area artists.

The mingling of modern art with material meant to appeal to a broader audience would continue for the first five years of Morley’s directorship—and at a pace that is astonishing. During the first year alone, she and her small staff mounted seventy exhibitions; they then showed between seventy-four and one hundred each year through 1941, when World War II intervened. Morley’s intention was to get the public into the habit of visiting frequently by making sure there was always something new on display. To increase the odds, she also took the unusual step of keeping the museum open late, until ten in the evening, six days a week.

Commenting on this innovation in the local paper, Morley lets her populist sympathies shine through: “Museums have long dreamed of open evenings, but virtually none in America have ever taken the step. . . . They felt that art was for the leisure class only. We are embarking on this new and democratic experiment in hopes that we will build up a regular following of art lovers whose days are occupied.”4 Open evenings had been the brainchild of trustee Timothy Pflueger, a leading Bay Area architect, but Morley had embraced his idea with gusto, recognizing the benefits of providing convenient access to the museum for day laborers, office workers, and artists alike.5

Those evening visitors were in for what today seems quite a feast. Morley generated a systematic introduction to European modernism through exhibitions by a who’s who of artists we now view as canonical: Max Beckmann, Georges Braque, Cézanne, Dufy, Gauguin, Vassily

Kandinksy, Paul Klee, Fernand Léger, Henri Matisse, Joan Míro, Picasso, Yves Tanguy. Many of these shows came on loan from galleries on the East Coast, while Morley originated others, such as the Matisse exhibition she mounted in 1936, which drew heavily upon the holdings of local collectors Michael and Sarah Stein.

6 There were also a number of important exhibitions borrowed from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, which in the 1930s maintained an active program of circulating exhibitions that were often a natural fit for SFMA.

In keeping with her vision of the modern museum as a site for experimentation, Morley presented the latest developments in a wide variety of media, including photography, experimental film, architecture, and landscape design. There were also exhibitions of what were termed “special phases of art”—a numismatic exhibition, a book fair, a fine printing display—which were of particular interest to groups who might not be regular museumgoers.7 She mounted shows exploring the “art” of everyday life, meant to demonstrate that art was not only a painting that hung on a gallery wall but was also to be found in simple, soundly designed objects and materials that were often readily available to the average consumer: cutlery, ceramics, textiles, furniture, and the like.8

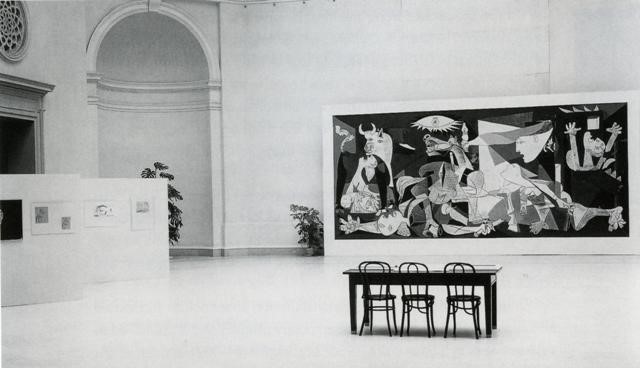

2. Pablo Picasso's Guernica (1937) on view in SFMA's rotunda, 1939. SFMOMA Archives

Morley’s “something for everyone” philosophy (with a heavy dose of modernism) was paying dividends by the time she presented MoMA’s Picasso retrospective in 1940. The exhibition, which traced the artist’s career from his early years in Barcelona through his monumental painting Guernica (1937; fig. 2), was met with such great public interest that on the evening it was to close, thirteen hundred visitors sat down in the galleries and refused to leave “until they had had their fill,” an event that was reported in more than fifty newspapers across the country.9 Years later, Morley recalled the impact the show also had on artists: “It was satisfying to see the stimulus that that sort of exhibition was to the artists, to see them responding, to realize that having great things of their period against which to measure their own work was important to them.”10

During the 1940s Morley’s focus began to shift in response to the increasing sophistication of her audience. The museum took on fewer traveling exhibitions in favor of those generated by its own staff, and there was a deliberate move away from European modernism toward the work of a new generation of American artists exploring fresh forms of expression in the abstract mode. Morley’s exhibitions of the work of Arshile Gorky (1941), Clyfford Still (1943), Jackson Pollock (1945), Robert Motherwell (1946), and Mark Rothko (1946) confirmed the emergence of the United States as a new center for avant-garde artistic production. They also underscore the San Francisco Museum of Art’s seminal role in support of this transformation: four of these exhibitions marked the first time the artist received a one-person show in a museum.11

With such a dynamic schedule, it is surprising to learn that in the early years Morley faced significant obstacles in bringing art to the West Coast. The distance was at once real and perceptual: in addition to the often prohibitive cost of shipping works thousands of miles and insuring them en route, she had to persuade lenders, many of whom had not even heard of the new museum, that sending their artworks was worth their while. Gallery owners in particular were loath to part with art they felt would have little chance of attracting a buyer in what they viewed as a provincial and unsophisticated market. Yet Morley refused to be daunted. She wrote persuasive letters to her Eastern colleagues expressing optimism about the opportunities presented by the virgin territory, and when that did not work, she resorted to subtle coercion to obtain a loan. In correspondence with one New York dealer, Morley acknowledged that while she could not guarantee sales during these lean years, she was confident that the continual exposure to modern art offered by SFMA would someday pay dividends to the patient and generous.12

Another way Morley tackled the costliness of shipping art to the West was through the Western Association of Art Museum Directors (WAAMD), initiated in 1921 by a group of art museums in the region to remedy this problem through cooperative planning and circulation of exhibitions.13 Morley joined the organization soon after the museum opened and, as was her habit, quickly took on a leadership role.14 Between 1935 and 1940 roughly thirty-two exhibitions at SFMA were either sent on tour under the auspices of WAAMD or were brought to the museum through the organization. On occasion, Morley would even bring shows to San Francisco that she was not particularly keen on in order to make them available to smaller, less-endowed institutions. Reams of correspondence reflect the extent to which museums from Seattle to San Diego benefited from Morley’s deft managerial skills and tireless advocacy on their behalf.

The educational activities Morley initiated during these early years, as diverse and inventive as the exhibitions, were also aimed at attracting the widest possible audience. Soon after the museum opened Morley introduced twice-weekly lectures focusing on current exhibitions, and in the fall of 1935 she launched a series of courses intended as a basic introduction to art history and appreciation. Like the exhibition program, the courses were meant to inspire a deeper understanding of modern art through the exploration of earlier artistic developments as well as present-day innovations. These courses, while intended for the general public, likely drew an audience of those at least already somewhat interested in and knowledgeable about art.

3. Girl Scouts attending a flower arrangement course, SFMA, April 26, 1939. SFMOMA Archives

Not wanting to miss out on any potential converts, Morley also created programming tailored to particular groups who might not otherwise find their way to any museum, let alone one focused on modern art. Her education file from 1936 contains sections on Boy and Girl Scouts (fig. 3), church groups, department stores, and labor organizations (the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, Bakery Wagon Drivers, and Window Cleaners unions), along with the more predictable art clubs and schools. Morley was often surprised at the results she achieved, something she reveals in a letter about the first gathering of the “labor group”: “They seemed to like their meeting and they are interesting to talk to for their reactions to art are very fresh, very sincere and they are not at all afraid to speak out their feelings. I enjoyed them and hope to make them feel art is something they should know about and find pleasure in.”15 The courses designed for this audience were geared toward helping relate art to their daily lives—and livelihoods—and included sessions such as “Art and Craftsmanship before the Industrial Revolution” and “Art and the Machine.”16

A substantial grant from the Carnegie Corporation in 1937 enabled Morley to reach an even larger constituency. A portion of the funds was used for a comprehensive three-year course covering the history of art through the present day along with participatory art-making demonstrations. In addition, there was the Extension Program, a series of prepackaged exhibitions centered on themes such as “The Language of Art” and “Personalities of Modern Art.” These installations were sent to public venues in rural communities throughout Northern California as part of Morley’s campaign to reach audiences that would not normally have access to the museum. Featuring original art and reproductions, explanatory labels, and prepared lectures, they were designed to provide “fundamentals of art understanding and appreciation.” In the first year alone they were sent to more than forty locations, reaching more than one hundred thousand people.17 “If California does not see an art renaissance within the next ten years it will not be our fault,” she wrote to a Cincinnati colleague.18

4. Grace McCann Morley and Delmar Gray, artist and shipyard engineer, in front of Gray’s painting Shift’s End (1941) at the opening of the exhibition Marinship Artists: Work by Bay Area Artists in Shipyards, 1943. SFMOMA Archives

Morley remained committed to active educational programming throughout her tenure. During the early 1940s there were programs aimed at soldiers and sailors, including the provision of art supplies for those wanting to take “Painting for Pleasure” classes, a Council for Art in Wartime to organize work opportunities for artists (camouflaging, poster design), and the Arts and Skills Program organized with the Red Cross to promote art as therapy for wounded soldiers (fig. 4). Despite other cutbacks, the museum retained evening hours “for the benefit of those busy during the day, and who more than ever will need now the reassurance of the persistence of the eternal human values which art represents so well,” as Morley wrote.19

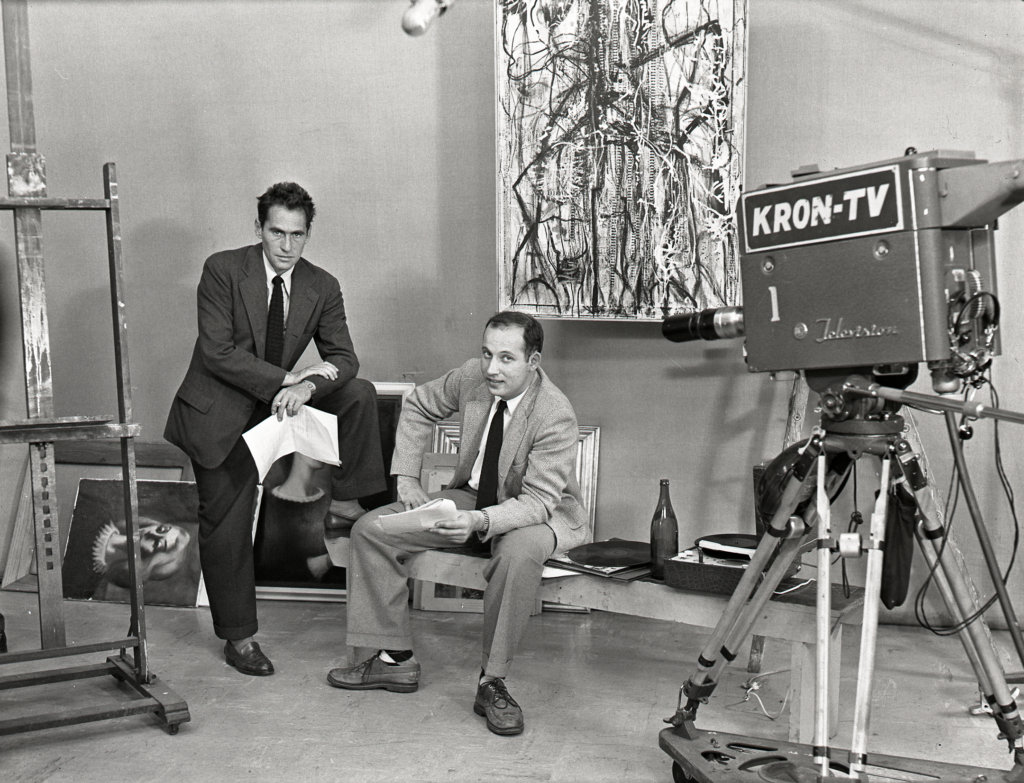

5. Frank Stauffacher and Allon Schoener on the set of Art in Your Life, 1951. SFMOMA Archives

In the early 1950s the nascent medium of television offered yet another opportunity for spreading the message of modern art with the series Art in Your Life (fig. 5), which brought contemporary art and artists into the homes of more than forty thousand viewers a week.20 Produced by SFMA staff and made possible by the donation of public-service airtime, the program took advantage of the particular strengths of the new medium by featuring personal interviews, demonstrations, and other visually compelling material that would “spread knowledge of art as radio enlarged the public for good music.”21

As Morley and the museum gained prominence during the late 1940s and the 1950s, she began withdrawing from the day-to-day operations of the museum in order to take on a number of high-profile international projects: organizing exchange exhibitions with museums in Latin America under the aegis of the U.S. State Department; serving as the first head of the Museum Division of the United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); and participating in the establishment of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), which instituted international standards for museum practice.22 When she finally retired from SFMA in 1958, Time magazine called Morley “the most respected woman museum director in the U.S.,” and Art News captured in a few lines the wide scope of her achievements: “Since her inauguration of the museum she has consistently and energetically supported our advanced artists, being perhaps more than any other person instrumental in overcoming the provincialism of the Far West, and has brought our art life closer and closer into contact with the vital currents of New York and also of foreign centers; furthermore, the international scope of her activities has resulted in the work of our artists being seen in many world centers.”23

Morley was leaving behind a thriving organization. Starting with the barest of bones, she had managed to assemble a collection of some three thousand objects and a membership of forty-four hundred. Attendance at educational activities hosted by the museum, from lectures and workshops to performances and films, averaged more than thirty thousand people a year.24 “Art is an inseparable and essential part of human life,” Morley wrote in a 1950 paper outlining her philosophy.25 Evidently, many Bay Area residents agreed with her. This conviction inflected every aspect of Morley’s career, from the exhibitions and programs she initiated in San Francisco to her later activities on the global stage. Her dynamic leadership in supporting avant-garde art and artists and in creating a vibrant, community-focused museum is only one short chapter in SFMOMA’s intriguing history, but her legacy lives on.

Notes

- Grace McCann Morley, “Art for Everyone: A Contemporary Museum Concern,” Spectator 4, no. 1 (Winter 1950): 10.

- Grace McCann Morley, “Methods of Education in the Art Museum,” unpublished paper, ca. 1939; 1939 Art Associations: Pacific Arts Association; Office of the Director 1935–58, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives.

- Harvard’s program, directed by Paul Sachs, was unique in that it addressed the vocational problems faced by museum professionals of the day, who were often trained as art historians without receiving any practical experience in museum operations. In addition to traditional art scholarship, Harvard’s curriculum included courses dealing with the ethical and philosophical issues confronting museum workers, as well as training in the areas of collection management, conservation, storage, and recordkeeping. Sachs firmly believed that “museums exist not so much to amuse as to educate the public,” and students in his program were instilled with the notion that a museum’s mission to educate was intimately related to their curatorial work. An entire generation of American museum directors and curators were graduates of what has been referred to as the “Fogg Factory” (after Harvard’s Fogg Museum, where many of the courses were held), and it had an enormous influence on the evolution of museums in this country. See Edward P. Alexander, The Museum in America: Innovators and Pioneers (Walnut Creek, Calif.; London; New Delhi: AltaMira Press, 1997), 206–7; and Edward P. Alexander, “A Handhold on the Curatorial Ladder,” Museum News 52 (May 1974): 23–25.

- “Galleries Stay Open Evenings: Art for All is Purpose of New Showplace,” San Francisco Examiner, January 19, 1935.

- Grace McCann Morley, “Art, Artists, Museums, and the San Francisco Museum of Art,” oral history interview conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1960, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 60–61.

- Michael Stein (brother of Gertrude) and his wife, Sarah, had recently relocated from Paris to Palo Alto, bringing with them a fine collection of European modernist art. Morley brought them into the museum’s fold with great alacrity. A number of works from the Stein collection were eventually given to the museum.

- Letter from Charles Lindstrom to Walter Barusch, March 17, 1936; 1936 General: A–E, L; Office of the Director 1935–58, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives.

- These types of exhibitions were also mounted at MoMA, New York, where Alfred H. Barr, Jr. wanted to create “a museum as various as the arts of the time in which it happened,” a museum that concerned itself with common cultural artifacts—a poster, a label, letterhead—and explored the “little, unnoticed and unsuspected corners in which the arts lived where people lived.” Russell Lynes, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of The Museum of Modern Art (New York: Atheneum, 1973), 73.

- Guernica had been introduced to the Bay Area public the previous year when it was exhibited at SFMA in its tour around the United States to raise awareness about Spanish Civil War refugees. San Francisco Museum of Art Quarterly Bulletin 1, no. 4 (Summer 1940): 20.

- Morley, Art, Artists, Museums, 219.

- Mark Rothko had a solo show at the Portland Museum of Art in 1933.

- Letter from Grace McCann Morley to Paul M. Byk, Arnold Seligmann, Rey and Co., Inc. (a gallery with offices in Paris and New York), April 22,1936; 1935 Women’s Board: Educational Committee Report through October 1935; Office of the Director 1935–58, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives. Museums often served as an important go-between for collectors, particularly in San Francisco, which during the 1930s and 1940s did not have an active community of private galleries showing contemporary art.

- Grace McCann Morley, “Exhibitions,” Art in America 34 (October 1946): 200, 205.

- In 1937 Morley was elected WAAMD president, a position she held for three years.

- Letter from Grace McCann Morley to Mrs. Edward Macauley, February 6, 1936; 1935–36 Educational Programs: Study Courses—Correspondence 1935–36; Office of the Director 1935–58, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives.

- Letter from Katherine Field Caldwell to the editor of Organized Labor, September 27, 1935; 1935–36 Educational Programs: Study Courses—Correspondence 1935–36; Office of the Director 1935–58, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives

- San Francisco Museum of Art Quarterly Bulletin 1, no. 1 (July–Sept 1939): 12; Letter from Grace McCann Morley to W. W. Crocker, April 1, 1938; Unprocessed Board of Trustees Correspondence; Office of the Director 1935–38, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives; and Letter from Grace McCann Morley to Mr. and Mrs. Walter H. Siple, October 23, 1937; 1937 Museums; Office of the Director 1935–58, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives. Walter Siple was the director of the Cincinnati Art Museum.

- Morley to Mr. and Mrs. Siple, October 23, 1937.

- News Letter for Members, March 1942; Calendar 1935–59, series 4: Periodicals, 1935–ongoing; Publications Collection; SFMOMA Archives; and “Wartime Adjustment at the San Francisco Museum of Art for the Greater Benefit in Service and for the Protection of the Public in Wartime,” unsigned article in SFMA’s monthly calendar, Your April Bulletin, April 1942. See also the Red Cross files, 1942 Red Cross; Office of the Director 1935–58, Administrative Records; SFMOMA Archives.

- Allon T. Schoener, “San Francisco TV Program Reaches 40,000,” Art Digest 26 (October 1, 1951): 10.

- San Francisco Museum of Art Quarterly Bulletin, 2nd ser., 2, nos. 1–2 (1953): 13. “Art in Your Life,” which aired on KRON, was later revamped as “Discovery” and aired on KPIX.

- After leaving SFMA in 1958, Morley briefly served as assistant director at the Guggenheim Museum in New York but then began a second career in India, where she applied her expertise in museum methods to guide a postcolonial country in the establishment of a national museum focusing on its own cultural heritage. In 1968 she founded ICOM’s Regional Agency for Asia, where she advised and supported museums in other developing nations. Morley died in 1984 in New Delhi, just weeks before a scheduled return to San Francisco for SFMOMA’s fiftieth anniversary.

- “Twenty-three Years of Grace,” Time, July 14, 1958, 56, 59; Herschel B. Chipp, “Art News from San Francisco,” Art News 57, no. 2 (April 1958): 48.

- Katherine Church Holland, “Introduction,” in San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: Painting and Sculpture Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1985), 22.

- Morley, “Art for Everyone,” 10.