Nam June Paik (1932–2006) was a voracious and attention-grabbing experimental artist. Recognized as the father of video art, he also mounted performances aimed to startle and shock his audiences, provoke laughter, and gain the attention of tabloid newspapers, network television, and even the police. Yet his wide-ranging art—especially the video sculptures, drawings, and installations he created in the 1990s and beyond—is loaded with surprisingly personal reflections on his life, family, and friendships that often reverberate with jolts of melancholy and joy. Paik’s sculptural installation Chongro Cross (1991), titled after the central district of Seoul where his family’s textile factory was once based, weaves together video, film, photography, and the artist’s legacy of experimental performance with traditional Korean rites of commemoration. Here Paik’s poignant recollections of his artistic and ancestral origins reveal his understanding that both old and new media serve as conduits for memory.

2. Paik pictured with his father, Lak-Seoung Paik, in 1933. Nam June Paik, Chongro Cross, 1991 (detail); collection SFMOMA, Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions; © Estate of Nam June Paik

Taking the form of a shrine, Chongro Cross combines video and photography with objects typically associated with ancestral worship. In the corners of the work’s wall-mounted display are positive and negative versions of two photographs: one of Paik at the age of one, seated in his father’s lap, and the other of Paik’s grandfather. Within this grid, video monitors play what Paik referred to as “the first P.R. films” for his family’s factory.1 When he discovered the reel, which was produced in 1929, he must have been pleased to see this early example of their use of film and self-promotion, art forms he had come to master.2 Intermixed with this footage is color video in which Paik is seen wandering the city of Seoul in a traditional Korean costume.3 On his back are wooden carriers, which are customarily used to harvest rice; in his performance, they hold globes. A fedora cast in concrete rests at the center of the display—the most recognizable symbol of his friend and longtime collaborator Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), who had died six years earlier. Arranged on the ground are objects—dishes, drums, and a ceremonial pipe—displayed as they would be at the base of a shrine on Lunar New Year or in commemoration of the birth or death of one’s ancestors. As a whole, the work pays homage to Paik’s artistic and ancestral families, calling attention to his global roots, East and West.

3. Excerpt of video footage from Chongro Cross, 1991; collection SFMOMA, Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions; © Estate of Nam June Paik

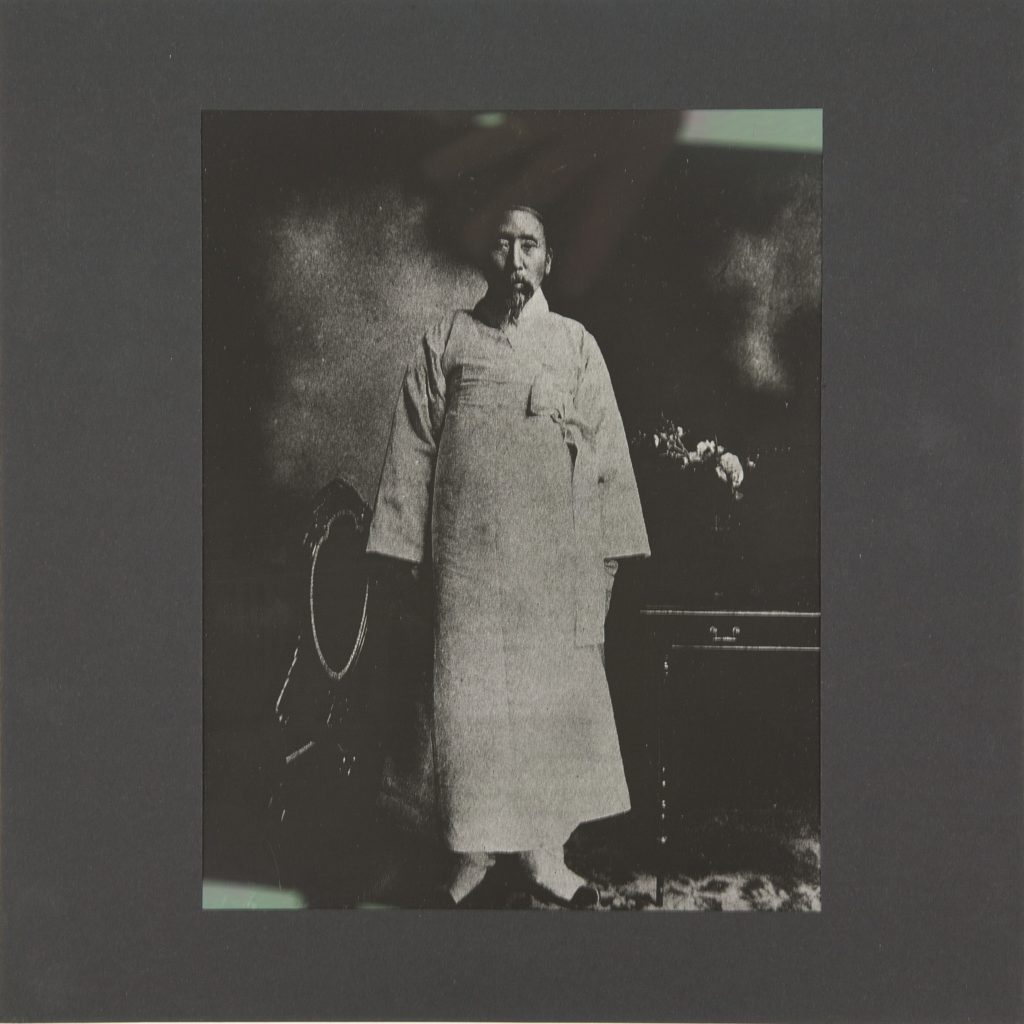

4. Paik’s grandfather, Paik Yun-su, in 1920. Nam June Paik, Chongro Cross, 1991 (detail); collection SFMOMA, Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions; © Estate of Nam June Paik

The worldwide ruptures of the mid-twentieth century were the foundation for Paik’s itinerant life. Born in Seoul, the artist immigrated with his family to Japan in 1950, at the age of eighteen, to escape the Korean War. After completing a degree in musicology and aesthetics in Tokyo, Paik arrived in West Germany, in 1956, to study experimental music. He soon began to work on the border of music and avant-garde performance, establishing close bonds with many artists who at the time were associated with Fluxus, including Beuys, Wolf Vostell (1932–1998), John Cage (1912–1992), and George Maciunas (1931–1978). The intensity of Paik’s relationships with these figures is evident in the enduring friendships they maintained beyond the height of their collaborations in the 1960s, especially in the case of Beuys, Cage, and Charlotte Moorman (1933–1991), who Paik met when he moved to New York, in 1964.

Recalling his unexpected first meeting with Beuys, in 1961, Paik later wrote, “I couldn’t erase the memory of this stranger from my heart, the image of a man who has never compromised himself in spite of innumerable difficulties.”4 Beuys had introduced himself at a Zero Group exhibition and proposed that Paik hold a concert in his studio. The initial meeting did not yield a collaboration, as Paik declined because he was intensely preparing for his first solo exhibition at Galerie Parnass. But over time they began to work together closely on music-centered collaborations. Beuys would become especially important to Paik; the two artists performed together at the Festival Fluxorum in 1963 and at happenings at Galerie Parnass, which was host to some of the most progressive art of the 1960s.5 The two performed together, for instance, in a joint concert in 1978 dedicated to Maciunas at the Düsseldorf Art Academy and in 1984 they traveled with one another from Düsseldorf to Tokyo, where they held the joint concert Coyote III, during which Beuys sang his guttural coyote sounds and Paik played the piano.6 During their final concert, Piano Oxygen, hosted by the Hamburg Peace Biennale in 1985, Beuys made his contribution via telephone from his deathbed.7

In 1984 Paik returned to South Korea for the first time since fleeing the country as a young man. The homecoming trip, spurred by the invitation to create a commission for the 1988 Summer Olympics, prompted Paik to explore his origins and the place of his birth.8 The surfacing of his past and his own fragile health, combined with the recent passing of Beuys, prompted a new phase of introspection and mourning that would continue for the duration of his career. In 1988 Paik exhibited numerous works in honor of Beuys in Seoul, at the exhibition Beuys Vox.9 As a further expression of this memorial, Paik held a performance commemorating his friend on July 20, 1990, in the backyard space of Gallery Hyundai in Seoul. As we will see, many of the elements incorporated into the work serve as the basis for Chongro Cross. The event, which was modeled on a Korean mourning ritual called Chinogwi-kut, was titled Nam June Paik + Shaman Exorcism Rite + Joseph Beuys’ Memorial Service, with subtitles including Dream of the Ural-Altaic Peoples and Shaman Exorcism Rite in Search of Time Lost.10

5. Nam June Paik, Chongro Cross, 1991 (detail); collection SFMOMA, Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions; © Estate of Nam June Paik; photo: Katherine Du Tiel

Chinogwi-kut is still practiced in Korea today. It is performed by a shaman, includes music and dance, and is intended to free (exorcise) the deceased’s spirit when it is unable to leave the earthly world because of an unfulfilled wish or unexpressed grievance.11 By joining the ritual with experimental actions in the spirit of his Fluxus roots, Paik honored his own beginnings as well as those of Beuys. This combination of old and new was a deliberate demonstration of performance art’s ancient lineage: a reference to Paik’s own actions, but most notably to Beuys’s intense and concentrated art actions, which were often remarked on for their shamanistic quality. Paik’s choice to carry out a ritual in Beuys’s honor, then, was intended to pay tribute to his spirit in the medium for which his friend was so well known. The subtitle Dream of the Ural-Altaic Peoples was an allusion to the two artists’ shared cultural origins, as Korean shamanism is believed by many to have originated in Siberia, a part of Eurasia.12 Beuys’s own self-created origin story began in that boundary-straddling region, in the Ural Mountains, where he claimed to have been nursed by indigenous Tatars after his plane was shot down during World War II. This experience was also the starting point for Beuys’s view of Eurasia as a symbol of physical and metaphysical unity between divided spheres. Adding particular urgency to their transnational lives and visions, both artists were born in countries that had been fractured by the Cold War: Beuys, who lived in divided Germany, and Paik, whose home country was partitioned between North and South in 1953.

A broken piano served as the central memorial site of Paik’s performance, an homage to Beuys’s startling destruction of one of the three prepared pianos at Paik’s first solo exhibition, Exposition of Music–Electronic Television, at Galerie Parnass in 1963. It was there, among a number of musical installations, that Paik had debuted his first altered TVs. He later recalled, “I heard some clattering noise from the adjacent room. I went out to find a man smashing the Ibach Piano into pieces with an ax. I went closer to the scene to find it was the ever-serious and funny man, Beuys.”13 During the ceremony in Seoul, Paik also created music from traditional bowls and saucers, transforming them into makeshift percussive instruments hung on string like laundry from a line, in a manner resembling the prepared kitchen tools he created for one of his earliest Fluxus performances in Germany, Zen for Hands (1962). The dishes and drums laid out in front of Chongro Cross evoke the ritual of leaving food for the deceased but are also offerings of music, which provided both artists creative sustenance throughout their lives.

Further entangling Paik’s memory of Beuys with his own life was the date of the memorial performance, which was also Paik’s birthday: July 20, 1932. This day held a special significance for Paik, as it also confirmed his place in a generation—along with Beuys—that was acutely aware of the political and humanitarian catastrophes of the twentieth century. As Paik wrote of this date in a text published in 1965:

July 20 1932 Day of the insurrection against Hitler, I was born in Seoul/Korea as son of my father and mother. . . . It was June 17th according to the Lunar Calendar (Day of Uprising against Stalin). At home I celebrate my birthday according to the old Korean custom on June 17th according to the Lunar Calendar, and in school and on my passport is the official July 20th birth date. I prefer this date, because, if the German Volk had been more against Hitler, the valuable blood against Stalin would not have been necessary.14

Paik’s musings reveal much about his international identity and the intensely close bond he felt with Beuys. It was not only the day Paik entered this world—on the same day in 1964, Beuys became the public figure we have come to recognize. The occasion was a festival at the Technische Hochschule Aachen. The most controversial event in the history of Fluxus, it was held in commemoration of the attempt to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944.15 At the festival, a photographer captured Beuys—who had been hit in the face by an audience member—with a bloody nose, making a Nazi salute and wielding a crucifix, in image that cast him as the face of scandal and Fluxus in Germany.16 This infamous performance triggered a lawsuit against the artist, pushing the larger questions of just who and what are to be remembered in the aftermath of the Holocaust and World War II and whether contemporary art had any place in addressing this history.17 Paik’s creation of Chongro Cross and his decision to mount his memorial performance to Beuys on this date reflects his deeply felt kinship with the artist. It is also a reminder that historical memory and commemoration were a part of Fluxus even in its earliest days and acted as a driving force throughout Paik’s life and career.

Notes

- Ken Hakuta, interview with the author, March 15, 2015, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

- Play it again, Nam! A portrait of Nam June Paik, directed by Jean-Paul Fargier in co-production with Canal+ and Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris: Canal+, 1990), video recording. In this biographical documentary, Paik dates this footage to 1929. My thanks to Jon Huffman for bringing this date to my attention.

- This video was made by Jean-Paul Fargier while he was filming Paik in Seoul, 1990. Related segments are included in Play it again, Nam!

- Nam June Paik, Beuys Vox 1961–86 (Seoul: Won Gallery/Hyundai Gallery, 1988), 1.

- Paik, Beuys Vox, 19.

- The performance took place at Seibu Museum Sôgetsu Hall on June 2, 1984, and coincided with exhibitions of Beuys’s work at Seibu Museum of Art and Paik’s work at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum.

- Paik offers his reminiscences of the concert in Paik, Beuys Vox, 77.

- For his Seoul commission, Paik created The More the Better (1988), an installation of 1,003 TV monitors at the National Museum of Modern Art, Seoul, and the live satellite TV event Wrap around the World (1988).

- The exhibition took place from September 14 to 30, 1988, at Gallery Hyundai and Gallery Won.

- For a description of the performance, including reference to these titles, see Oh Kwang Su, “Nam June Paik, Beuys and Shaman Exorcism Rite: A Search for the Original Form,” in A Pas de Loup. De Soul a Budapest, ed. Nam June Paik (Seoul: Won Gallery/Hyundai Gallery, 1991), 60–67.

- For a detailed anthropological account of Chingowi-kut, as well as a brief description of this particular practice, see Hyun-key Kim Hogarth, Kut: Happiness through Reciprocity (Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, 1998), 57.

- James H. Grayson, Korea: A Religious History, 2nd edition, (London: Routledge, 2002), 19.

- Paik, Beuys Vox, 22. Beuys’s action was likely in reference to Paik’s piece, One for Violin Solo (1962), in which he dramatically lifted the classical instrument above his head and smashed it in front of him.

- Nam June Paik, “Nam June Paik,” in Happenings, Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Realisme, ed. Wolf Vostell and Juergen Becker (Reineck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1965), 444–45.

- The festival was officially titled “Actions, Agit Pop, De-coll/age, Happening, Events, Antiart, L’autrisme, Total Art, ReFluxus, Stücke und Aufführung von Andersen, Beuys, Brock, Brouwn, Christiansen, Filliou, Gosewitz, Köpcke, Schmit, Vautier, Vostell and Williams.” The Fluxus Festival was not originally planned as a commemoration of July 20, 1944. However, it seems that in an emergency measure to keep the performance on the scheduled date, the organizers acknowledged the significance of the date in their final preparations before the event. All of the artists, who arrived a few days before it began, were notified that the festival was officially recognized by the school as a commemoration. Adam C. Oellers, “Wollt Ihr Das Totale Leben?”: Fluxus Und Agit-Pop Der 60er Jahre in Aachen: Katalog Zur Ausstellung Im Neuenaachenerkunstverein, 14. Januar-19. Februar 1995

(Aachen: Neuer Aachner Kunstverein, 1995), 9. - Paik was not able to attend the festival but instead designed the festival’s poster. The lawsuit against Beuys was brought by the Committee of Survivors and the Bereaved of July 20, 1944, for public mischief (grober Unfug). See documentation in Oellers, 82.