The historic landscape photographs of Yosemite often celebrated as monuments to US wilderness conservation also chart histories of loss and resurgence for the seven Traditionally Associated Tribes of Yosemite: the Bishop Paiute Tribe, Bridgeport Indian Colony, Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe, North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California, Picayune Rancheria of Chukchansi Indians, Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation, and Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians.1

Photography was invented ten years prior to the 1849 discovery of California gold. Its first decades of use coincided with the United States’ territorial expansion across the Great Plains and the West.2

These years witnessed tremendous loss of Indigenous life, land, and rights. In California, state-sponsored killing militias made the 1850s the most chilling period of genocidal violence and land theft. The first Americans to enter Yosemite Valley in 1851 belonged to one such militia. While they scorched villages and massacred and kidnapped Ahwahnechee Peoples (today identified as the seven Tribes of Yosemite), militiamen with the Mariposa Battalion hardly noticed the valley’s majestic rock formations and waterfalls.3

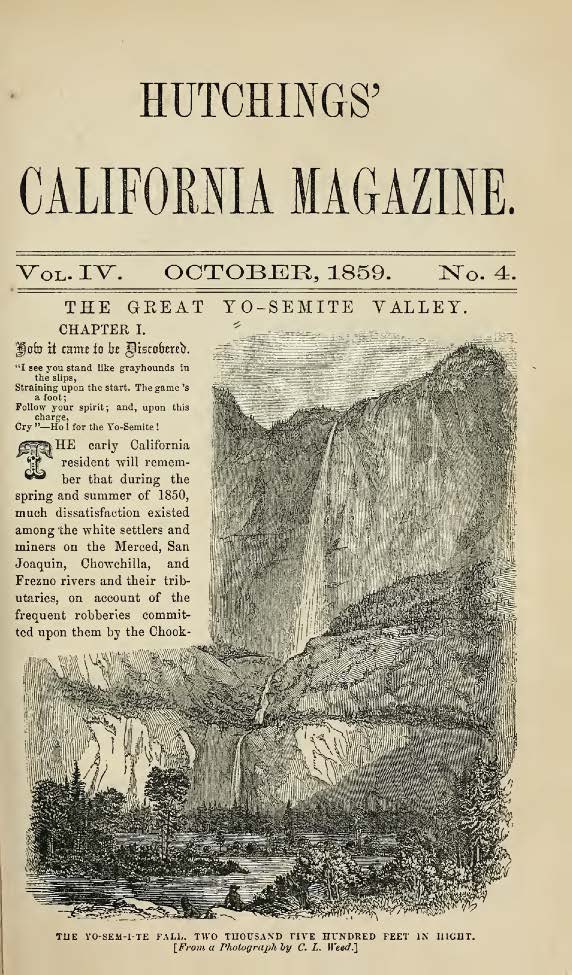

Early landscape photographs of Yosemite must be understood within this historical context of efforts to eradicate California Indians and dispossess them of their land. The first photographs made of Yosemite Valley by Charles Leander Weed in 1859 and Carleton E. Watkins in 1861 were commissioned by James Mason Hutchings to promote tourism at his newly completed hotel. Weed’s photograph of Yosemite Falls was reproduced as a front-page lithograph in Hutchings’ California Magazine in an article announcing the “discovery” of Yosemite (fig. 1). Alongside the image appeared an embellished narrative justifying the massacre of Native Peoples for petty crimes.4

Watkins’s Yosemite photographs helped to clinch the dispossession of Ahwahnechee land when several prints accompanied the proposal sent to California Senator John Conness petitioning for the protection of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove from private development (fig. 2). Watkins’s framed photographs on Conness’s office walls reportedly persuaded Abraham Lincoln to sign the Yosemite Act in 1864, granting the land to the State of California for public tourism.5

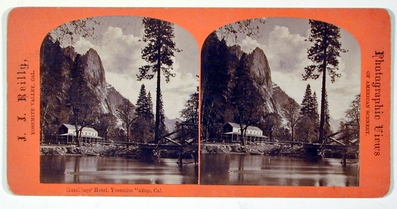

Although the legislation ostensibly protected Yosemite from rapid ruin, it also marked the beginning of an era when livestock and increasing mobs of non-Native tourists would wreak havoc on the landscape every summer. Meanwhile, the Native community was prohibited from caring for the land to sustain both themselves and Yosemite’s ecosystem. J.J. Reilly’s stereograph Hutchings’ Hotel, Yosemite Valley, California is telling of the drastic changes that occurred in a short time span (fig. 3). Where one of the most prominent Southern Sierra Miwuk villages buzzed with Indigenous life for thousands of years stands the colonial structures of Hutchings’s Hotel and Sentinel Bridge. This stereograph was part of the popular 1870s collection Photographic Views of American Scenery that beckoned non-Native people to enjoy Yosemite and other recently pilfered lands as the United States’ own “natural” heritage. Accordingly, nineteenth-century landscape photographs should be considered signals of occupation. Even without the presence of colonial figures, views of nature were important to the mission of genocide and dispossession. The environmental historian Jarrod Hore writes, “Nature, for settler photographers and their audiences, was not only beautiful, ancient, and empty, but an object that disguised the realities of Indigenous presence and reinforced colonial fantasies of environmental abundance.”6

The images Watkins made during his several visits to Yosemite from the 1860s to the 1880s reveal how his perspective on nature accomplished colonial aims. Visual culture historian Martin Berger observes that Watkins alternated between images that focused on singular geological features and those that provided distant overviews of the valley. These scenes reflected the value white Americans placed on the valley’s most monumental features.7

Photography thus fragmented Yosemite into a set of awe-inspiring rock formations, waterfalls, and trees to be aesthetically consumed. Yosemite’s legendary views have been endlessly repeated in landscape photography and popular culture since the nineteenth century. Eadweard Muybridge, Ansel Adams, and countless other photographers imaged the same sites Watkins made famous. Even today, these photographic views are remade thousands of times daily by tourists who snap the iconic scenes they have come to know as Yosemite’s quintessential sights. On any summer day Inspiration Point, where Weed and Watkins made the first wide Yosemite vistas, is so crowded that visitors must wait their turn to stand elbow-to-elbow with others wishing to photograph the famous view. Roger Minick pokes fun at this fact in Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park, CA, in which the view of Yosemite Falls printed on a tourist’s headscarf mirrors that of Bridalveil Fall in the distance (fig. 4). Minick implies that the view the tourist sees before her is the one already drummed into her head. This fragmented consumption of Yosemite in images has a real-world impact on Native Peoples and the land. It celebrates aesthetic appreciation of an “uninhabited wilderness” at the expense of recognizing Indigenous histories and worldviews. As environmental historian Mark Spence argues, “Uninhabited wilderness had to be created before it could be preserved.”8

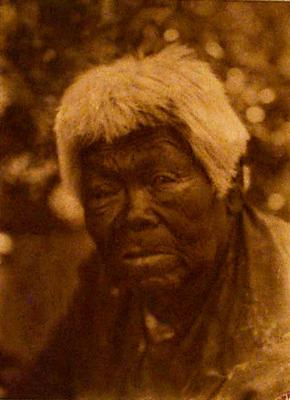

The creation of national parks and the forced removal of Indigenous Peoples were two sides of the same coin. Nineteenth-century landscape photographs aided in the creation of public parks because they aimed to assuage white Americans’ anxieties about the loss of the natural world at the hands of commercial enterprise. Romantic landscapes encouraged a sentimental vision of natural places as ancient sites worthy of preservation. Meanwhile, “salvage ethnographic” images paradoxically proposed that whites were “preserving” for science a record of a “vanishing race.” Melancholic photographs of Indigenous Peoples, such as those Edward S. Curtis made of Lucy Brown (Southern Sierra Miwuk) and other tribal Yosemite Peoples, framed them as ancient peoples fated for extinction (fig. 5). These depictions concealed the facts of genocidal violence by presenting annihilation as part of an inevitable natural process. Together these two genres of images obscured the constitutive relationship between Indigenous Peoples and pictured landscapes—that of stewards with a rightful title to their homelands. Nevertheless, photographs that had Indigenous ends in mind testify to the persistence of Native Peoples at Yosemite. A significant number of photographs of Native Yosemite Peoples feature basket weavers such as Callipene (Southern Sierra Miwuk), who survived the 1851 invasion (fig. 6). The art historian Jolene Rickard (Tuscarora) notes that the unstated goal of such photographs was to contrast the technological advancements of Western civilization with Indigenous Peoples’ lack thereof: “[An] effective way to establish the technological acumen of Native people was to document their production or ‘level of technology.’ The basket is handmade from the materials of the earth, relegating it to a ‘low’ in contrast to ‘high’ mechanistic form of technology.”9

These photographs fit the genocidal stereotype of Indigenous Peoples as anachronistic and ill equipped to survive in a modernizing world. However, as Rickard notes, that message fails to take account of the fact that “the basket is a significant innovation and invention of human ingenuity.”10

Prior to colonization, basketry was a prominent Native women–led industry in California. The making of a basket employed centuries-long ecological research on the cultivation of desirable weaving materials. Dr. Lafayette Bunnell, who documented the 1851 invasion of Yosemite, dedicated pages of commentary to the impressive variety and uses of baskets utilized by Native Peoples. He especially marveled at cooking baskets “made of a tough mountain bunch-grass, nearly as hard and as strong as wire, and almost as durable. So closely woven are they, that but little if any water can escape from them.”11

The plant scientist Kat Anderson explains that the virtuosity achieved by Native weavers resulted from their integral connection to their homelands: “Weavers tended and gathered from the same places generation after generation, applying ancient cultural knowledge in the process of directly converting plant materials into cultural objects.12

After colonization, Native Yosemite women created new basketry designs to sell to tourists and to gain employment in the park’s cultural programs. Photographers working for the National Park Service and tourists alike made numerous images of weavers like Lucy Telles (Southern Sierra Miwuk/Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a) (fig. 7). Despite non-Native photographers’ patronizing view of their subjects, these pictures document creative Native resistance to colonization. By the twentieth century the park service’s anti-Indigenous rules and regulations had replaced the killing militias of the nineteenth century. But their attempts to evict Indigenous Peoples were no less vigorous.13

By continuing to weave, women maintained a place for their families on their homelands and earned international acclaim. They also passed down knowledge that supplied younger generations with a vital connection to their culture. Their master baskets, like Telles’s famous large 1933 basket (fig. 8), demonstrate a deep knowledge only possessed by those with intimate ties to land developed over centuries of intergenerational stewardship. In other words, these photographs of weavers and their baskets should be regarded as documents of the seven Tribes of Yosemite’s legitimate Indigenous Title to their homelands.14

Yosemite landscape photographs also unwittingly picture Yosemite as Native land. For instance, Watkins’s 1861 photographs of parklike montane meadows reveal the diversity of grasses, shrubs, and midsize and large trees resulting from careful ecological practices such as annual burning, pruning, and selective harvesting (fig. 2). These Native gardening techniques refined the width, length, straightness, uniformity, and pliability of desirable basketry materials.15

They also maintained wide-open meadows and kept the view between trees clear for hunters. In contrast, Adams’s later photographs of Yosemite show that the forest fell into disarray without necessary annual human disturbances. With the prohibition of Native ecological methods, trees overtook the montane meadows and became denser and slenderer as they competed with each other for sunlight.16

Taken together, nineteenth- and twentieth-century landscape photographs illustrate American settlers’ ignorance of Native Peoples’ advancements in science and technology. The valley American settlers claimed to have discovered was no uninhabited wilderness, but a garden carefully managed by innovative Native communities. If photographers’ intent was to show Yosemite as a vacant place to be aesthetically appreciated but left untouched, they failed at that task. The images instead testify to the intricate knowledge of Yosemite’s ecosystems, confirming Native presence and the necessity of Native land management. Despite the disastrous effects of settler colonization, the seven Tribes of Yosemite persist in their relationship to the land. Photographer Dugan Aguilar (Mountain Maidu/Pit River/Walker River Paiute descended) applied the techniques he learned studying with Adams to celebrate the vibrance of California Indian life. His 2005 photograph of Helen Coats (Southern Sierra Miwuk) portrays an ecological intimacy uncharacteristic of the fragmented monumental views made by settler photographers (fig. 9). Coats sits tucked into the secluded spot where her grandmother Telles pounded acorns. The stone underfoot holds Coats’s felt connection to her grandmother and conjures her cultural legacy. Telles’s mother survived the Mariposa Battalion massacre. Telles instilled younger generations with cultural knowledge and pride. Twenty-first-century generations carry on the deliberate persistence of their elders and ancestors. The Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation and Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe (which both lack a land base because of the conservation of public lands) today continue their resistance to colonization in their fight for federal recognition. Today’s generation has also at last persuaded the Yosemite Conservancy to value the ecological knowledge of the Native community. Tribal peoples are partnering with Yosemite National Park to reinstate cultural fires based on their Traditional Knowledges. Cultural ecologist Irene Vasquez (Southern Sierra Miwuk), with the guidance of ancestors, elders, and tribal partners, is currently leading the restoration of black oak ecosystems.17

These intergenerational ecological relationships—past, present, and future—are anchored in Aguilar’s image of Coats. He pictures Yosemite land as a relational place woven into the fabric of Native life since time immemorial. The history of photography at Yosemite is one of national myth and colonial violence, as much as it is also one of Native presence and resurgence.

Notes

-

- I am grateful to Emily Dayhoff (Southern Sierra Miwuk) and Irene A. Vasquez (Southern Sierra Miwuk) for their generosity in contributing to this article and for providing feedback.

- See Jolene Rickard, “The Occupation of Indigenous Space as ‘Photograph,’” in Native Nations: Journeys in American Photography, ed. Jane Alison (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1998), 57–59.

- Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 103–230, Yosemite at 186–94; Lafayette Houghton Bunnell, Discovery of the Yosemite, and the Indian War of 1851, Which Led to That Event, 3rd ed. (New York: F.H. Revell Co., 1892).

- The Great Yo-Semite Valley,” Hutchings California Magazine 4, no. 4 (October 1859), 1. On narratives used to justify massacres, see Madley, An American Genocide, 188.

- Hank Johnston, The Yosemite Grant, 1864–1906: A Pictorial History (Yosemite National Park, Yosemite Association, 1995).

- Jarrod Hore, Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022), 6.

- Martin Berger, “Landscape Photography and the White Gaze,” in Sight Unseen: Whiteness and American Visual Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 49–50.

- Mark David Spence, Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 4.

- Rickard, “The Occupation of Indigenous Space,” 63.

- Rickard, “The Occupation of Indigenous Space,” 63.

- Bunnell, Discovery of the Yosemite, 94.

- Kat Anderson, Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 189.

- Spence, Dispossessing the Wilderness, 101–32.

- Indigenous Title refers to the Indigenous Right to collective ownership of their homelands.

- Anderson, Tending the Wild, 187–207.

- Anderson, Tending the Wild, 119, 156–58.

- Irene A. Vasquez, “Acorn Is Medicine, Restoring Reciprocal Relationships with Black Oaks and People,” California Society for Ecological Restoration, Davis, CA, 2023; Irene A. Vasquez, personal communication with author, June 2023.