Over the past decade, sculptor Anna Sew Hoy and writer Litia Perta have developed a friendship built on conversations about making, introspection, and compassion. In recent years, they’ve written alongside each other in workshops, met to discuss mothering as an act of care, and shared notes on the process of creating work, then releasing it into the world. Here, they turn their focus to the sculptures in Sew Hoy’s New Work exhibition and how they connect to experimentation, failure, resilience, motherhood, and more.

Litia Perta: It’s funny — when you’re visiting a museum, the presentation looks so seamless. People don’t often think about how the object gets into the gallery. I was so moved by the photos documenting the making of Coil Uncoiled, Furl Unfurled and the photo of the crack. I also loved your email about it, and that you put “failure” in quotation marks, because it’s not the right word. I kept thinking instead about trial and attempt as part of process — like a necessary part of methodology when you’re working with things that are basically science at the same time as art. You’re making your own path.

I want to hear more about your process of making that piece, because it seems related to your meditation practice. I keep thinking about practice as a thing to which you return. You don’t know what’s there, but you return to what you don’t know, over and over again. What nourishes you in that? How do you keep doing it? Can you tell me how you keep coming to the kiln, over and over again?

Anna Sew Hoy: The kiln is a place where things transform through fire. I go to it again and again because I want to make something I’ve never seen before, and working with clay is where I access mystery and possibility. It’s also fraught with breakdown — cracking, coming apart, loss. When I build something in clay, I’m inventing the steps that will result in a new form. I try something and it doesn’t work. I change the steps and try it again. There’s failure, growth, changing the steps, changing them again, and finding out what to do next by process of elimination.

Coil Uncoiled has a rounded shape that looks like the shoulders of a portrait bust or a multiplying cell. I started making the coil forms in around 2019. They were much smaller, around 20 or 22 inches wide. The ones that I made for the museum are four feet wide — four times the size of the previous piece I made using this shape. When they didn’t make it through the firing six weeks before the museum ship date, that was a pretty devastating blow. Even though we fired them slowly, we didn’t fire them slowly enough. Each piece is 250 pounds of clay and it’s thick, and large sculpture needs to be treated more delicately than smaller objects by orders of magnitude, like when you’re measuring an earthquake. It’s almost like it’s got to be squared or cubed — that much slower. So that was the clay telling me what I needed to do next time.

I’m not working on only one thing at a time; I’m working on several things at the same time and allowing for pauses and circling back and correcting mistakes. It does feel like science in that way, and I do experiment with process. So there is success and failure, meaning I either take the right steps towards my goal, or I need to adjust. Having a show is kind of like dipping into the continuity of my work, because I’m always working on a few sculptures at once.

Part of the preparation for this show has been to take the forms I was already working on and scaling them up to fit the larger gallery. It’s been a joy to try to figure out how to do that; I love logistical problem-solving. It always hurts when something breaks, especially close to a deadline, but that’s part of the practice. I can’t say that I work in an unattached way, because I definitely feel the attachment once the piece is lost. But I love the challenge and the problem solving — the satisfaction of getting it right and the feeling of discovery.

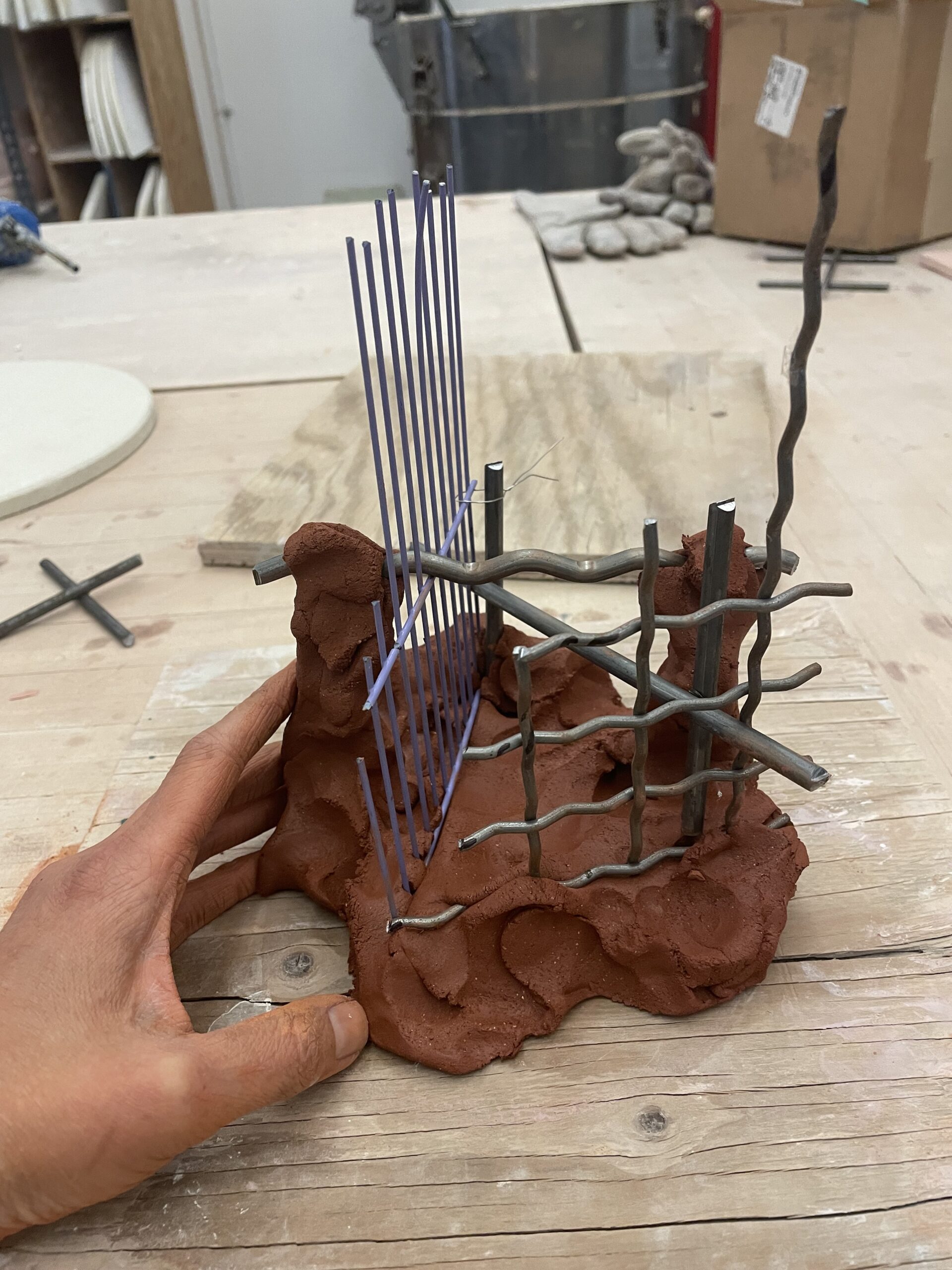

Progress shots in the studio with Angelica Starcovic, Maya Buffett-Davis, Lee Sew Hoy and Harlan Goldman-Belsma

LP: When you are preparing for a show, do you have any feeling about whether you want viewers to know this part of the process? It’s hard, I think, for people to imagine that there may have been two of these 250-pound structures that needed to break in order to get to the pair we are seeing in the exhibition space. Is that in your mind as you are making, or do you trust that they’ll feel the heft of the process?

ASH: When viewers are in the gallery, I don’t think they necessarily know what it took to make the works, and I don’t expect them to know. Making stuff is really, really hard in different and specific ways. But there are things that I want them to know about what I was doing. I hope for my work to have a physical clarity — a legibility of gesture. With the Coil Poem pieces — that’s the nickname for Coil Uncoiled, Furl Unfurled — I want you to remember being a kid and making a coil pot. Coil building is a simple, basic, universal hand-building method. That’s why I left the exterior of the coils visible, so you can see how it was made and you can imagine, “Okay, so she took the coils and laid them on top of each other and created a shape.” I want you to understand that and to feel the action of laying coils on top of each other. Looking at this piece should trigger a muscle memory in you.

LP: Adding the fire element brings it into an alchemical space, where it opens up to some kind of deep unknown. I think all your work does this in a way that I struggle to put words around, but I know when I’m in the gallery, your works really open to unknowing — like inviting the unforeseen element in. There’s also so much play in your sculpture. It’s like an invitation to come closer. And now that you’ve added language [to your sculptures], a viewer needs to physically get near the piece if they want to read the words. There’s something beautiful about that gesture of having someone come toward or come in.

I said heft before, but that’s not quite right: it’s more like layers of work, engineering, trial and error, and the joy of having a vision that might at first seem impossible. If you talk to a fabrication expert about what you’re envisioning, they might say, “No way you’re going to be able to do this.” There’s something joyful about the connection that you have to your vision. You just keep going. As a viewer, when I’m in a space with your work, I may not know the story, but I can feel that approach to practice, to experience, to living through form in quite a literal way. It’s not that it isn’t attached to outcome — it is, because we’re human — but it’s clearing something away and then starting again, with more knowing. There’s something beautiful about that rhythm, and I feel like it’s palpable when you’re in the space.

I want to ask one more question about the Coil Poem pieces. I want to hear more about your writing. There’s something embodied in the way that you write and the way that you come to language. It doesn’t feel mental, as in divorced from body and form and material. Instead, it feels very much like another channel for it. And I don’t know how you do that, because that’s really hard to do with words, but I love what you came to in the final version. At some point in our conversations, you talked about how parallel lines never meet but they’re connected somehow, each doing the same thing in their own way. That got me thinking about that pair of works in the gallery, because parallel lines are in relationship, partly because they’re close: they are near to each other.

Something about your writing and your practice beckons us closer — encourages us to make intimacies in space with the work. And now with the words, it feels like another skin, another layer. Language sits in bodies in different ways, and maybe some viewers will read aloud to each other, like if there are parents with children who don’t read yet. You can imagine language in the space amplifying out in ways that are unexpected or unforeseen. Your writing generates intimacy and nearness. It seems like that’s the space that writing holds for you — a turning inward. It does seem like that gesture is a witnessing gesture.

ASH: Witnessing is a good word to start with, because I’m using language to witness the sculptures, and what I want the sculptures to do, how I imagine them to be operating. You’re right that I’m involved with the interiority of writing, of going inside to get a thought down: “What is my body doing, feeling, hearing, sensing?” Putting a thought on paper externalizes it.

I make sculpture to externalize and share a thought-action; when I’m making something in the studio, thought and action are the same impulse. But how can this work connect with someone? How are they getting information from that form? It’s so hard to put that into words, because it’s thought, action, and material. And so I really wanted to try to use language — to not explain literally what the sculptures are supposed to be doing but more as an analogy.

For Coil Uncoiled, I wrote on a large square of paper, starting from one corner and following the edge, continuing along each side in a continuous spiral. Then I tried writing words in a continuous line on a long roll of paper — a stream of writing. The words came out differently this way. They had their own pace and unfolding, unfurling if you will.

I thought that if you can understand what my words are doing within language — because people are more used to reading words than confronting abstract sculpture — then that’s something you can connect to. Like when I use jeans, which are something familiar, in my work. So then, if you can read the words and think about what the words are doing, then maybe you realize that the sculptures are doing something analogous with matter, with clay, with jeans.

LP: That’s beautiful. Also because analog is parallel, right? Analog is nearby, but not touching. Is that how you think about the jean seams?

ASH: Yeah, jeans and cell phone cords. Because the cell phone cord is this thing that’s in your daily life that you really need and it’s always around, but it’s also a line in space. And then everybody has a sensory memory of what it feels like to wear jeans, or you have a very personal memory of your favorite jeans, or you have a desirous feeling about some jeans you can’t afford. I think that association with a material is really fascinating — that a material can be like a touchstone for those emotions or memories or feelings or history.

LP: I hadn’t been thinking about it like that. I was thinking about structure and invisible structures that hold up your jeans. I think that’s, again, a beautiful and generous invitation to something that’s familiar that then allows you to see the unfamiliarity or the unknowing of what a line is doing in space and then letting you connect it to your body in a way that’s familiar.

ASH: I will let you in on a funny thing I’ve been doing lately, which is taking a snapshot of my kids’ lunches every morning. They have these colorful bento boxes with four compartments of different sizes, and I have to fit the food to each differently sized compartment using what I have in the fridge while also understanding what they want to eat that day. Making their lunches is like playing Tetris or doing a crossword puzzle — making something that fits. Where is the art in our lives? What’s the daily practice? I think it’s in all these different places. This sculpture is where I put my best practice in, but it’s also fed by all other moments, like the lunch-making.

LP: I feel like people think of mothering as “person in control” and “little one.” But actually your practice of mothering acknowledges that there’s a fully formed human you have to regard as equal, but who is also entrusted to your care. That requires so much creativity. In your sculpture, you engage familiar things so that someone might experience mystery in them again. It feels like a gesture full of integrity: making sure we have some sense of familiarity — like the bento box for your kids — but allowing us to interface with what we don’t know — like every time the lunch is different. There’s also something beautiful about the way you speak of the materials in the sculptures. It feels like there’s so much regard for a viewer coming in.

ASH: Thank you. Yes, I want to share my reveling in the minute details of jeans, of sandwiches, of the hand-building process in clay. It’s seven in the morning on Monday and I’m blasting pop music, arranging the colors, shapes, and textures of lunch foods. It is really like I’m sketching. Jump in! Stay in the texture and color and enjoy daily stuff through that, too.

Photo courtesy of Anna Sew Hoy

LP: I remember when you and your family visited us — you had on-the-go watercolor palettes that came out at the same time as the sandwiches when we all went on a hike. If you felt like you wanted to make something right there on the beach, you’d brought the tools you needed to do that. I thought it was a beautiful invitation for any human, but certainly for younger humans to realize that making is everywhere, both in terms of a circle of stones (which you also left trails of) and more recognizable practices linked to daily practice. It seems like fashion is like that for you too: there’s deep joy in what you choose to put your physical body in, and a high regard for the fact that the body is the tool — the temple — and you adorn your body with things that feel comfortable. There’s a line in one of your writings: “Coil uncoiled, furl unfurled, black hair streaked with sweat and shower water, soft clothes only.” It’s only things that feel good: materials that are soft. There is deep pleasure in so many aspects of life that we’re taught are not important or that you can pass over to get to the office or whatever. But your work, your daily practice, reclaims that joy: you show up with regard for seams. I loved what you said in one of your texts: “A clay coil and a strip of paper are both infinite lines to me.” You meld so well the “minutia” of daily life with the elements of abstraction.

I’m curious in terms of process: In your Growing Ruins pieces, do you draw out the clay and cage shape first? How do you start?

ASH: It’s such a journey. I’ve been making arched clay shapes, which I call Grottos, for ten years. With those, it’s about how to use the arch form to frame out space and allowing that space to be the main player. Psychic Body Grotto, a public sculpture in the LA State Historic Park, is my largest expression of holding space.

The cages were added into my practice around 2016 when Trump was in office and people trying to enter the country were being held in detention centers. The US was separating and detaining children. My friend Lucas Michael collaborated with Mary Ellen Carroll on a project to raise awareness of the situation at the border by using children’s accounts taken by the Flores investigators, so it’s really their words: “There are many sick children here. They take them away. We do not know where the sick children go.” “There are a lot of mosquitos here. The mosquitos are big, and they bite us all the time, even on our legs under our pants.” We artists were asked to find words within these interviews to make a drawing from, and I ended up drawing that arched form with a cage inside, so my Growing Ruins sculptures began with this project by Lucas and Mary Ellen, and thinking about imprisonment, oppression, and getting out.

I decided to make the drawing three dimensional. I found bird cages and dog crates — gridded metal — and built clay arches around that metal and then fired it all together. It didn’t come out like what you see in the watercolor, because the fire transformed it. I hadn’t predicted what was going to happen — that when the clay surrounding the cage dried and contracted, it cracked around the metal. When the whole thing was fired in the kiln, the metal slumped under the intense heat. I discovered this really dynamic relationship between the metal grid and the squishy clay. They altered each other. And that’s how the sculptures started, from that very dynamic coming together of two materials and their transformation in the fire.

After that, I had to answer the next problems that arose because of the piece’s fragility after firing. I ended up embedding the cage-grotto structure into a plaster base to protect it. But these pieces also have a weird strength. They’re not that fragile. Like a spider web, their strength is in their interconnectedness — the weave or network structure they possess.

The other part that I got a lot of joy out of was warping the grid. I found a way out of the grid by warping the cage bars to open up different spaces.

Psychic Body Grotto, 2017, at the Los Angeles State Historic Park. Photo: Jeff McLane

LP: I love that you said they alter each other, and then to bring in a spider web which has its resilience in the interconnectedness of the form and the ability to move — it’s not so rigid as a grid or a cage. I had no idea that the origin was Lucas and Mary Ellen’s project and the politics of that. Even the notion that you are also altered, as many people were, by that happening. And that it made you look more carefully at what cages can do and what they can’t do: what they resist, and what happens if you put them in fire. It’s beautiful that the cage or the grid structure weakens, but that the structure as a whole becomes more resilient by introducing elements of play, rebellion, and joy. You said it beautifully: that you are interested in the cage but also in getting free and in parts that can’t be caged.

ASH: I could have stopped where the clay and the cages meet in the kiln. There’s a simplicity there, but I had more to invoke with this work. Some of the last steps are about re-inhabiting the structure with stuff like the flattened bottle caps strung up, or the bits of plastic which are collected and deposited within. That’s a key part: making the work feel inhabited and like it’s thriving — taking what’s around, and then using it to make the space wild and exciting. These sculptures are really maximal, and I think it was important to show that abundance and color and activity.

Over the pandemic, I read Anna Tsing’s Mushroom at the End of the World. I was thinking a lot about different South Asian refugees like the Hmong, who are now living in the industrial wasteland of the Pacific Northwest forests. That’s what happens with forests; they have a cycle. When pine trees die, they become the perfect environment for matsutake mushrooms, which are valued in Japan as a delicacy. But most people don’t know how to find matsutakes, so the Hmong and other people who live in this forest collect the matsutakes and make a living selling them to Japan for money. As I was making the sculptures, I was thinking about making a life within ruins, which is what the book describes.

LP: You mentioned that there are stages to making these sculptures and one is a phase of thriving and abundance. If the viewer looks closely, they’ll see things from daily life made into art, like bottle caps and keys.

ASH: Yes! The added bits! It was important that they not just go into the Growing Ruin sculptures as-is, but that they were changed by at least two processes before going in. The bottle cap doesn’t stay just a bottle cap. We found them in the alleyway after being run over so they became really flat like a coin. And then we put a circle of fabric on the back of each one to make a dot of color, and we nailed a hole in each to string it up. So each bit of detritus or trash that we found transformed before we added it to the sculpture. My assistants and I spent weeks with the stuff that we collected, putting it together and transforming it.

Some of this stuff I’ve been thinking about for a long time, including a disco ball that the artist Rosha Yaghmai loaned me once for a party that I never returned. I had Rosha’s disco ball up outside for years. Rain fell on the disco ball, the sun shone on it, and then the wind blew it. And then finally all the papier-mâché inside decomposed, and the mirrors started to fall off onto the ground. At that time, my kids entered a potion-making stage. They were putting petals and leaves and mirrors in cups of water, and then leaving their potions outside to rot. While I was making the Growing Ruins, I noticed the mirrors again. I’ve gone out into the yard four times over the past year to collect them from the dirt. I think I’ve finally gotten all of them. So that disco ball really fed the work multiple times, and I’m very grateful to it and to Rosha.

LP: I love the implication that art is everywhere. I think visitors will feel it. Your sculptures invite life in: there’s at least two operations that had to happen in order for these things to become this abundant form.

Your work is instructive for me because I’m often so tight around word-making. There’s something beautiful about the abundance of trying again and again, and editing and then trying again, and allowing daily life to infuse all of it, and not being so rigid about what the outcome is but staying connected to a vision. Your work feels so punk rock to me, like, “Yeah I can make art out of anything.” And not in a “fuck you” to the viewer, but in a “how many viewers can I invite in with all of the material I find in the alleyways where I live, and that over time ripen into the perfect material that life makes and that I can’t buy in an art store.” It’s about resuscitating life into life again.

There’s something so rebellious about that. Let’s fire the cages! And then adorn them with things that are considered trash — the stuff that this culture doesn’t want to see — and let’s bring it back and put it in a gallery with an attitude of, “What kind of party can we make with this? What kind of experiment? What kind of adventure?” It feels like a real way-making for a world. There’s something beautiful about not holding too tightly to outcome but staying deeply connected to a vision, whether that’s a vision for a piece or a vision for your children’s futures, or a vision for collective planetary futures.

ASH: Yeah. Maybe the work is to show all these other possibilities, and to keep all the unvoiced stuff present, because that’s the important stuff.

About Anna Sew Hoy:

Sew Hoy is represented in museum collections including SFMOMA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; and the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. She has had solo exhibitions at the Aspen Art Museum; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Hammer Museum; the San Jose Museum of Art; and the Orange County Museum of Art. Honors include the Guggenheim Fellowship for Visual Art (2022); Anonymous Was A Woman Award (2021); Creative Capital Grant for Visual Art (2015); California Community Foundation Grant for Emerging Artists (2013); and the United States Artists Broad Fellowship (2006). In 2017, she was the inaugural Martha Longenecker Roth Distinguished Artist in Residence at the UC San Diego Department of Visual Arts. Sew Hoy is currently Associate Professor and Ceramics Area Head at the University of California, Los Angeles.

About Litia Perta:

Litia Perta is a writer, teacher and parent whose work unsettles violent paradigms that sell us separation and call it truth. She is a white, queer, (mostly) gender compliant femme who engages intuitive critical practice and reconnecting to body (earth) to support people in the rebellious acts of nourishing their creative joy. Her PhD is from the Rhetoric Department at the University of California, Berkeley, and she is an alumna of the Whitney Independent Study Program. Most recently she is the writer of a book of lyrical essays making its way into the world. She lives on an island in western Washington state.