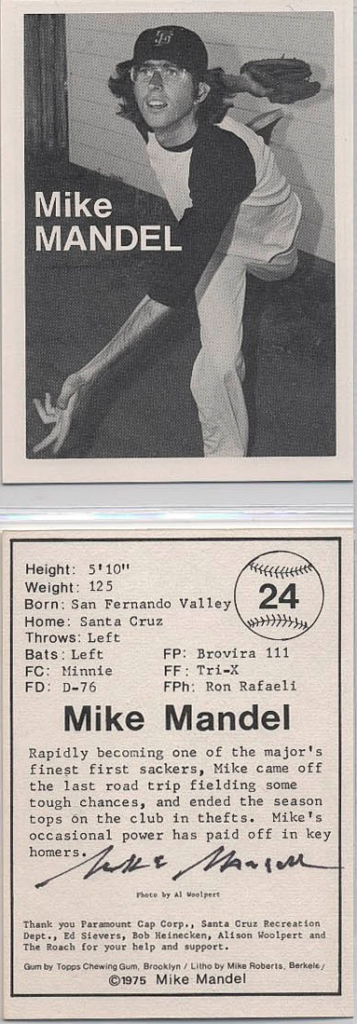

Mike Mandel, Baseball-Photographer Trading Card #24 (Mike Mandel), 1975; courtesy the artist; © Mike Mandel

Mike Mandel waxes poetic when he describes the graceful arc of a baseball card through the air. These days it’s something of a lost art, but when he was a kid and really, really into the San Francisco Giants, baseball card flipping was a native skill among his friends. “When I got to be a teenager, my father told me I should give my collection to the kid across the street—and I can’t believe I did it!—but then later on I realized I could re-collect the 494 cards issued the year I was shooting for a complete set, 1958. I’ve got most of them now, except the ones that are really expensive.” That year, 1958, was the year Major League Baseball arrived on the West Coast, where Mandel grew up. The Giants left New York for San Francisco, and the Dodgers left Brooklyn for Los Angeles. Up to that point, the farthest west Major League Baseball had traveled was St. Louis.

“My father had to explain it all to me. I started reading about the Giants, watched the box scores in the paper. It was something you could have an everyday connection with: who the players are, who’s doing well, who’s hurt. And it continued from year to year. Back then, players would stay their whole career with the same team. It was a significant, important aspect of my growing up.”

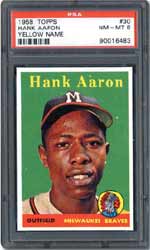

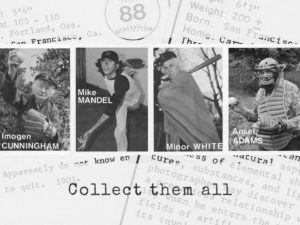

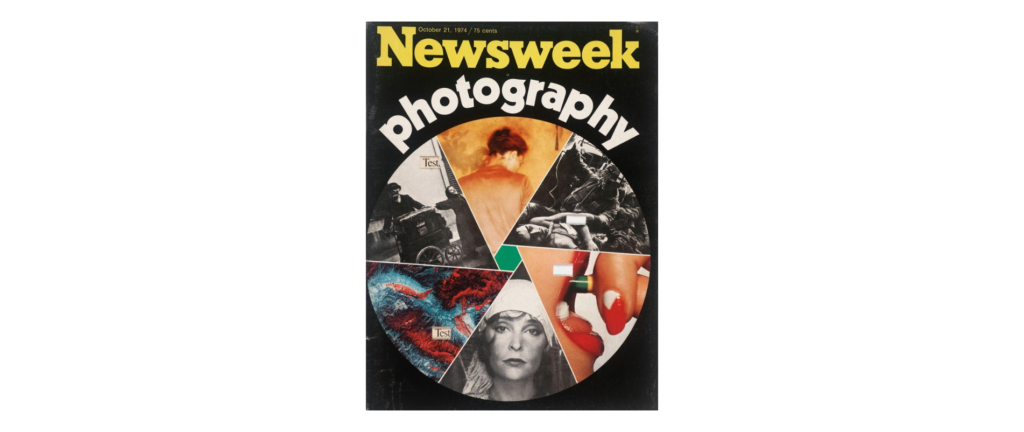

A selection of those cards are on display at SFMOMA as part of Mandel’s Good 70s solo exhibition—not as art objects in their own right, but as complements to his 1975 series Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards. At the time he made them, Mandel had recently graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute and was noticing with dismay how quickly the photography world was professionalizing. “I remember a particular Newsweek issue—the date was October 21, 1974—that was ‘all about photography.’ Suddenly people who were doing great work were being separated into groups: those who were going to be accepted by the art world and those who would be bypassed.” So it seemed like a funny, ironic project to create baseball cards for all the “well-known” photographers, to commoditize them in his own way, and have them “play” along.

Robert Heinecken, Newsweek, October 21, 1974, 1974; Collection SFMOMA Accessions Committee Fund purchase; © The Robert Heinecken Trust, Chicago

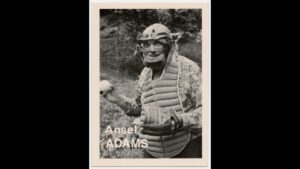

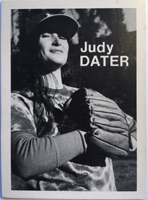

“Back then Ansel Adams didn’t have ten secretaries standing guard between him and the rest of the world; you could just call him up.” So he did. It took a few months to get the entrée, but in the meantime he’d recruited Imogen Cunningham for the project, which greased the wheels for access to pretty much anyone else he wanted. (Mandel affirms that it was Cunningham’s idea to wear that Mao cap.) The back of each card enumerates statistics like those that appear on the back of a normal baseball card: height, weight, hometown, and the like. But Mandel also included photographer-specific stats, such as preferred camera, favorite photographer, and so on, plus a statement of the artist’s choosing. “Some of them were very funny! Some of them tried to be funny. Some related an anecdote. It was a way of furthering the collaboration.”

Mandel traveled the country with his then-girlfriend for the project, crashing at the photographers’ houses when possible, staying at cheap motels the rest of the time. (Collecting postcards from all those motels became a project in its own right.) When he was done, he printed three thousand of each card, talked the Topps company into donating forty-five thousand sticks of gum (just like in packages of real baseball cards), and organized a group of friends for a packaging party (ten to a package—again, just like the real thing).

Mike Mandel, Untitled, from the series Motels, 1974, printed 2017; courtesy the artist; © Mike Mandel

“Every kid’s desire is to get the whole set of baseball cards for a particular year,” Mandel says. “Completism is inherent to collecting them.” And even though he didn’t approach the project with a defined plan as to how the cards would be received, he was “wonderfully surprised” to see the behaviors of the photography fans so closely mimic those of baseball fans. “I just figured I would get them into museums, photo galleries, and that naturally some interest would develop. I didn’t know ahead of time whether it would be a huge success or more of a conceptual moment.”

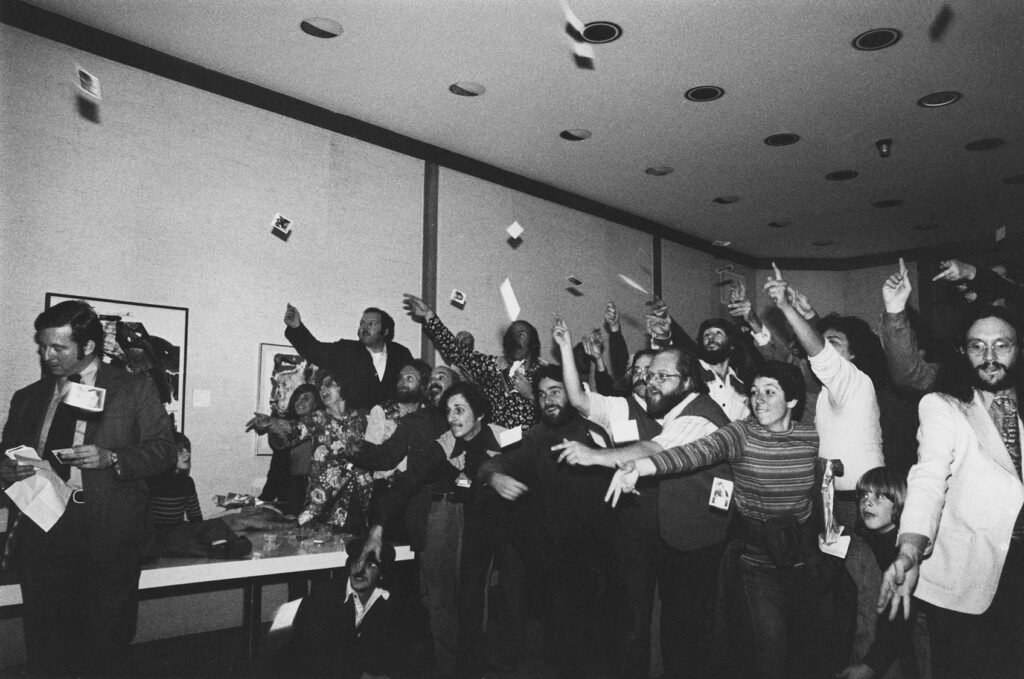

And yet what followed was pretty extraordinary. “Sports Illustrated, Newsweek, and Popular Photography all ran articles at the same time! It took off. Museums across the country organized trading card parties. You couldn’t get a full set without trading, so you had to find people with extras. If they were interested, they had to come together.”

The trading card party at SFMOMA, he recalls, was memorable. Many people showed up, and some had their cards on a big framed board, or were getting the various photographers to sign them. There was a card flipping contest, and the person with the longest flip got thirty-six packs, a whole carton!

“They sail in a beautiful way.”

Photo: Mike Mandel

Mandel even got a call from the TV show To Tell the Truth. The setup would be the usual: three mystery people, the narrator, and four panelists. The narrator would intro: “This person made those baseball photographer cards you’ve been hearing about,” and then each of the mystery people would tell “their” story about the project, and the panelists would guess who the real Mike Mandel was. “But they wouldn’t pay for my plane fare, so I didn’t do it. What an incredible missed opportunity to have a video thing on the cards! Although I have to say, the media translates something interesting into something dopey every time.”

Today, collectors of all kinds (including SFMOMA) continue their endeavors to amass the entire set. Just like the 1958 baseball cards, Mandel’s photographer cards surface regularly on eBay; impassioned completists with the time and the money can find a way to scratch the mysterious “collector’s itch.” As any collector of anything will tell you, part of the lure is the thrill of the chase — whether at a trading party with new friends or alone late at night, scouring the Internet, imagining likely artist name misspellings that might just lead to a rare find.

Sandra Phillips, SFMOMA’s curator emerita of photography who is organizing Mike Mandel: Good 70s, collaborated with Mandel on the display for the cards — one that would bridge the artist’s youth, his period of intense productivity in the 1970s (hence the show’s title), and his creative sensibility today. They settled on a stack of three rows: one showing the 135 cards’ fronts, one showing the 135 cards’ respective backs, and a third showing a selection of 135 cards from Mandel’s 1958 MLB collection that he has selected for their serendipitous correspondences to the photographer cards. “Sometimes,” notes Phillips, “the similarity is in the person’s physical gesture or pose. Sometimes it’s about the names. The idea is that it’s humorous but also formal.”

In Phillips’s eyes, the project is less satirical and more elegiac. “It was a different time back then. Things were more fluid; think for example of the work of Robert Heinecken, or Tom Marioni and his crowd. The photography market was still developing. A project like the baseball cards was embraced because it was so social, so open. Not subversive, but against the grain in a way that was in the air — lots of experimentation with a generous spirit.”