by Johanna Gosse

Bruce Conner completed his final film, EASTER MORNING (pl. 256), in the months before his death in July 2008. As the culmination of a half-century of his filmmaking, EASTER MORNING registers Conner’s long-standing interest in film’s capacity to represent, and, in a sense, to master, the unruly flow of visual and sensual experience. At the same time, it suggests a relentless pursuit—however provisional, flawed, and asymptotic—of transcendence from the specificities of time and place, the limitations of the flesh, and the vicissitudes of the everyday world. Moreover, as his last film, and one that was produced exclusively as a digital edition, EASTER MORNING also pushes us to reconsider Conner’s work in the context of the early twenty-first century.

If Conner’s trademark style of rapid-fire montage and audiovisual appropriation are recognized as key strategies within contemporary art practice, these superficial markers also appear to structure the broader digital ecology of everyday life.1 Recycled sounds and images proliferate in mainstream media, serving as constant reminders that appropriation can be used just as readily for cultural affirmation and profit generation as for critique. Indeed, Conner’s strategic use of appropriation anticipated the political and economic issues that have accompanied the shift to an information society, for instance, those associated with intellectual property, copyright, and creative commons. In this sense, his work functions as an urtext not only for music video, but for subgenres such as the remix, supercut, mash-up, and various practices of parodic or critical media intervention that flourish on user-generated video sharing platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo.

When Conner decided to finally venture into the digital realm, he did so with some apprehen- sion and much guidance from Michelle Silva, his editor and primary collaborator on THREE SCREEN RAY (2006, pl. 252). For that work, Conner and Silva translated his trademark found-footage strategies to a digital platform by taking advantage of the postproduction capacities of editing software. Yet, for EASTER MORNING, the move to digital was more a matter of convenience and control than of structural or formal necessity. Even so, Conner’s motivation to complete this work in the last months of his life points to its significance as his final word on film, time, and mortality.

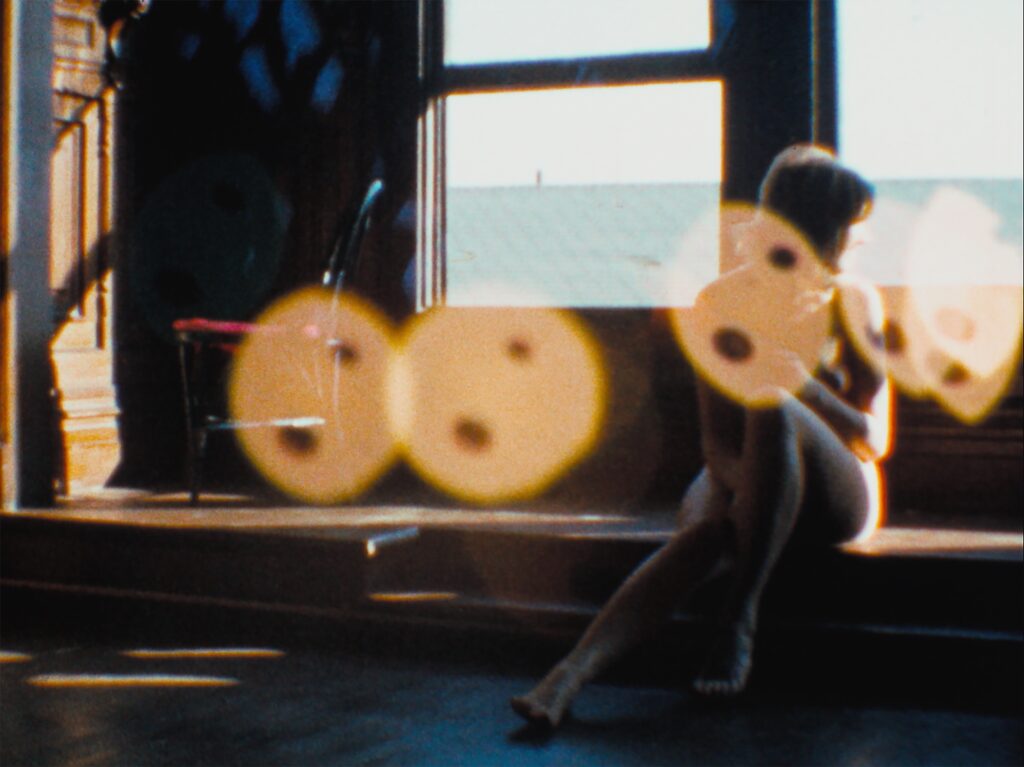

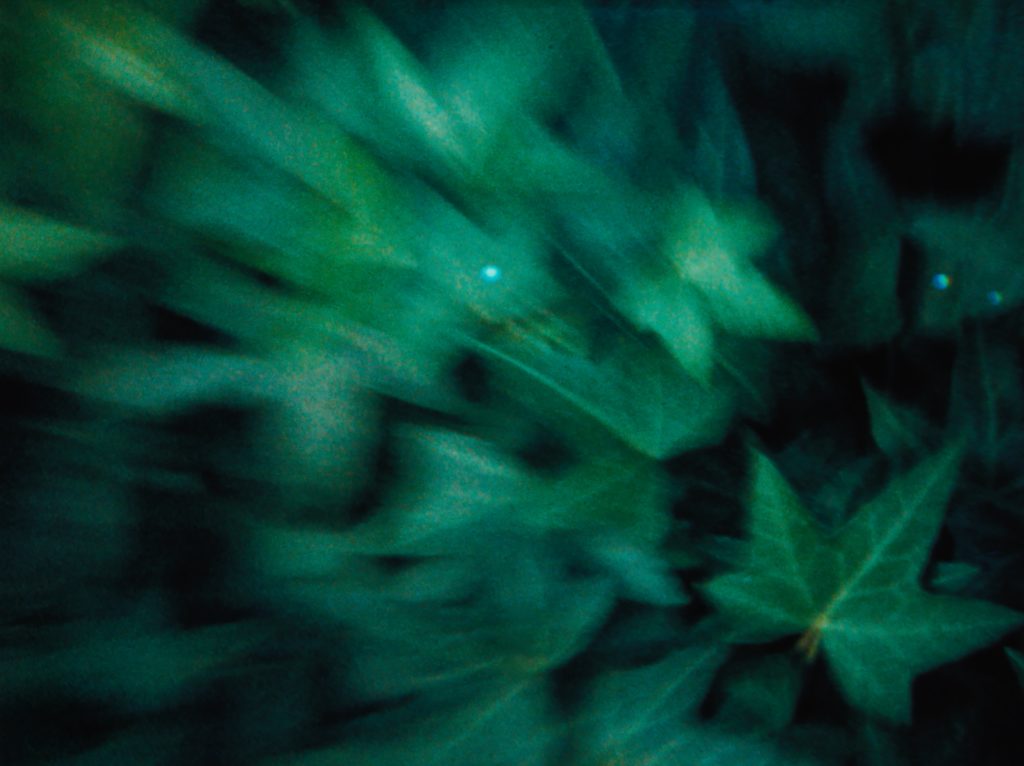

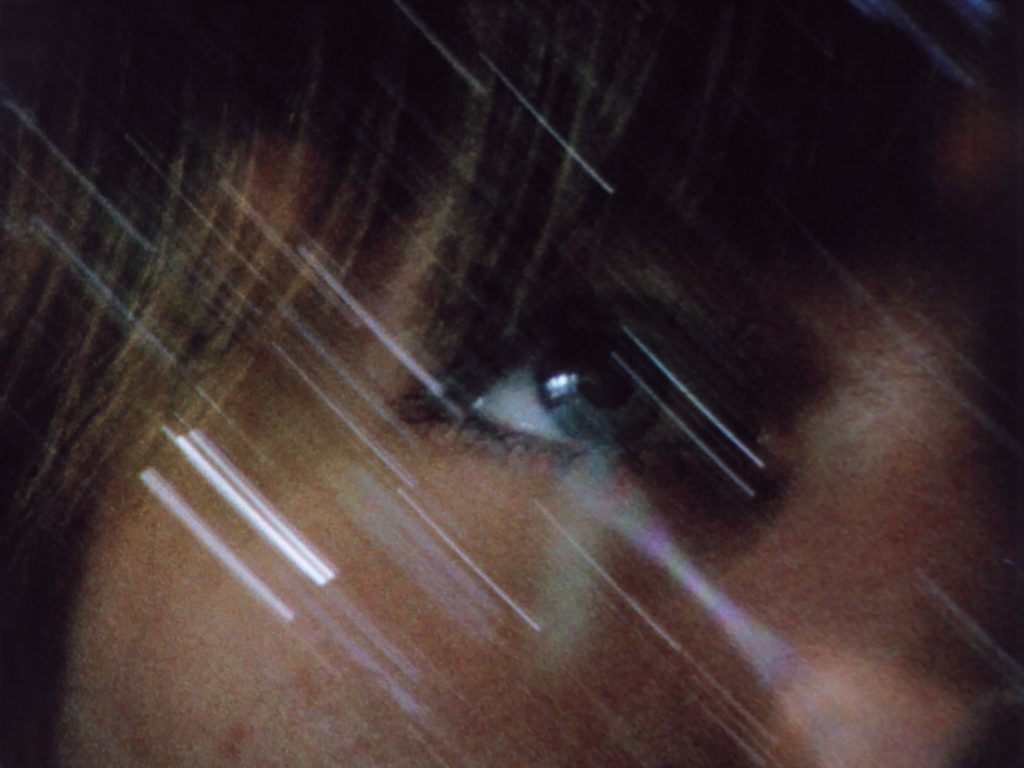

The footage seen in EASTER MORNING is derived from an unfinished 1966 film called EASTER MORNING RAGA, which Conner shot himself and edited entirely in camera, leading him to refer to it as his “perfect film.”2 The imagery in EASTER MORNING includes kaleidoscopic multiple exposures of plants, flowers, and nocturnal streetlights, intercut with shots of a nude, seated woman (Suzanne Mowat), as she poses next to a windowsill on a bright Sunday morning. These images are paired with close-ups of the graphic patterns on an Oriental rug and stark shots of a white stone crucifix perched against the blue San Francisco skyline. The imagery draws from a set of iconographic themes that recur throughout Conner’s body of work, including the nude female body, Christianity, and memories from his Midwestern childhood. The latter is symbolized by the inclusion of an Oriental rug, which recalls Conner’s narrative of his first out-of-body, mystical experience at age eleven—a critical scene in the artist’s personal mythology.3

EASTER MORNING features a soundtrack by minimalist composer Terry Riley, In C (1964), a phase composition intended for varying orchestral ensembles. Conner selected the Shanghai Film Orchestra’s interpretation of Riley’s score, which is performed on antique Chinese instruments. The clanging, archaic tones produced by these instruments suggest a sense of historical and geographic distance and otherness, which, in turn, amplifies EASTER MORNING’s atmosphere of enigma and mystery. Structured by Riley’s phased repetition, the soundtrack reinforces the notion of physical transcendence suggested by the film’s title, iconography, and staccato, slow-motion montage.

The title of EASTER MORNING refers to both the date and time of filming, and to the ritual sunrise service performed during the springtime celebration of Christ’s resurrection. Conner’s invocation of this Messianic event situates his film within the specific, calendrical time of an Easter Sunday, as well as the metaphysical, proleptic temporality of the future anterior, the foretold “what will have been” of death, redemption, and salvation. Yet, with the original title’s inclusion of the term “raga,” Conner coupled the eschatological temporality of Western Christendom with the more melodic, improvisatory, and less fixed temporality of the Hindu classical musical form, as if to propose a union of conflicting timescales, theologies, and histories. Thus, while EASTER MORNING draws from a common vocabulary of visualmotifs and themes familiar within Conner’s work, it also embeds them within an expanded, nonlinear approach to cinematic time, a hallmark of his filmmaking since the 1960s. From the hyperactive, subliminal montage of COSMIC RAY (1961, p. 51); to the delirious, drug- infused rhythms of LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS (1959–67/1996, pl. 62); the bodily dematerializations and reverse-loop form of BREAKAWAY (1966, pl. 20); the profane resurrections and staccato montage of REPORT (1963–67, pl. 84) and MARILYN TIMES FIVE (1968–73, p. 351); and the apocalyptic, glacial unfolding of CROSSROADS (1976, pl. 125), Conner used film to perform radical inquisitions on vision, time, and the body.

As a digital “re-vision” of an incomplete film from the 1960s, EASTER MORNING reflects a set of concerns and preoccupations that are consistent across Conner’s five-decade filmmaking career. Yet, as his cinematic finale, it also marks the apotheosis of his aesthetic exploration of the “atomic sublime,” the paradoxical experience of “terrible beauty” that characterizes his films since A MOVIE (1958, pl. 9).4 This sublime union of opposing forces—Eros and Thanatos, awe and fear, desire and dread—is echoed in the notion of an Easter morning raga, the imaginary soundtrack to both an end time and an eternal becoming, which hovers between the analog past and the digital present, in anticipation of futures unknown.

This essay first appeared in the exhibition catalogue “Bruce Conner: It’s All True” edited by Rudolf Frieling and Gary Carrels and published I 2016 by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in association with University of California Press. © 2016 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Notes

1 Countless artists and filmmakers have drawn inspiration from Conner’s pioneering use of found footage and pop music appropriation. See Cut: Film as Found Object in Contemporary Video, exh. cat., ed. Stefano Basilico, Lawrence Lessig, and Rob Yeo (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum, 2004).

2 For the final, 2008 version, Conner transferred the original 8mm Kodachrome to 16mm film, and then used an optical printer to step-print the footage, multiplying the frame rate 5:1 to stretch its duration fivefold. The result is similar to the slow-motion 1996 version of LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS (pl. 62) that uses Terry Riley’s “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” (1968) as its soundtrack. After utilizing this analog, frame-by-frame printing technique, Conner then had EASTER MORNING transferred to digital video, which is how it is exclusively distributed today.

3See Gary Garrels, “Soul Stirrer: Visions and Realities of Bruce Conner,” in this volume.

4The term “atomic sublime” provides the theoretical framework for my PhD dissertation, “Cinema at the Crossroads: Bruce Conner’s Atomic Sublime, 1958–2008” (Bryn Mawr College, 2014).