Suzanne Lacy’s work is collaborative by nature. An artist and a performer, she has created ephemeral work, which must be re-staged, or photographed for posterity. In celebration of her retrospective Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here, the SFMOMA Library and Archives presented her other collaborative thread, her participation in a network of feminist art publications and other printed materials meant for circulation. Largely from the 1970s, these works are a living witness to the issues of Lacy’s time, especially in regards to the attitude toward art created by women. The following are a selection of publications and materials from the SFMOMA Library, which bring forward these eye-opening historical documents.

In a themed issue on artists’ books for the magazine Art-Rite in 1976, curator, activist, and writer Lucy Lippard wrote that she was interested in artists’ books as a useful method for the dissemination of new art and ideas, a kind of broadcasting service for artists whose work did not necessarily fit traditional contexts for display in commercial galleries or in museums. Particularly, she wrote, artists’ books “open up a way for women artists to get their work out without depending on the undependable museum and gallery system (still especially undependable for women). They also serve as an inexpensive vehicle for feminist ideas.” Adding, “I’m talking about communication but I guess I’m also talking about propaganda,” Lippard saw the possibility of these informal publications as a new genre for artists to utilize for their work and ideas, as a way to have a public practice and a way for distributing information about that practice on their own terms.

For the feminist art movement of the 1970s, this strategy was a necessary tool for connecting local and international communities of women artists and to create alternative networks for these artists to discuss and promote the equitable representation of women in the art field. Publishing on a small scale was a primary format for artists trying to carve out a hospitable space for work that wasn’t accommodated elsewhere. Themes of advocacy, support, and consciousness-raising were central to many of these feminist publications. These themes were adopted from broader conversations in the women’s movement and applied by women artists to foster community in a climate where women were mostly excluded from the art market and from exhibiting in museums.

In the context of the Suzanne Lacy exhibition We Are Here at SFMOMA and YBCA, we traced how publishing became a vehicle for feminist ideas within the art communities that related to Suzanne Lacy’s early artistic practice and, generally, the beginning moments of feminist art practices on the West Coast in the 1970s and into the early 1980s. In artists’ books, exhibition catalogues, feminist art magazines, and printed exhibition ephemera from the SFMOMA Library, we can illustrate a network of women artists from the 1970s who were connected through a few alternative spaces such as Womanspace and the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles or through new experiments in feminist art education at the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State and CalArts, and in several thematic shows of women artists, such as those organized by Lucy Lippard or Eleanor Antin and by faculty and students at the Feminist Studio Program. Artists like Judy Chicago, Faith Wilding, Miriam Shapiro, Eleanor Antin, Suzanne Lacy, Lynda Benglis, Adrian Piper, and Betye Saar participated in these shows and their exhibition catalogues provided useful spaces to circulate artists’ works and convey conversations on themes of feminism and working as a female artist in the “undependable museum and gallery system.”

The statistics of the time relayed a grim report on the level of representation of women artists in shows organized by major museums. Relatedly, for collectors and gallerists of the era, women’s art was considered a bad investment. Individuals like Lippard and other women artists and curators made attempts to promote and organize exhibitions for women, and also protested the exclusion of women from major exhibitions in art hubs like New York and Los Angeles. Women in the American art community began to take space for themselves in various ways. Alternative art spaces like the New York–based A.I.R. (Artist-in-Residence) Gallery, founded in 1972, developed programs devoted to women artists and group exhibitions on feminist themes.

A special issue of the feminist newspaper Everywomen from May 1971 was edited and produced by the collective of women in the Fresno State Feminist Art Program. Designed by Sheila de Bretteville, the special issue features descriptions of the founding of the program by Judy Chicago, documentation of student work and written reflections by students in the program, including an essay by Suzanne Lacy, entitled “After Consciousness-Raising What?” In 1970, artist Judy Chicago started the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State and cultivated women-only spaces in art education to develop solidarity among young women artists. Creating room for new kinds of conversations about the shared experiences of women, Chicago developed consciousness-raising activities that promoted the history of women’s contributions in art and culture.

In fall of 1971, Chicago and Miriam Shapiro moved the Feminist Art Program to CalArts in Valencia, CA. Their first major project with the students in the new program was the construction and development of the Womanhouse project in an empty house in Hollywood at 533 Mariposa Street. The students renovated the house to host an installation project in which invited artists and students in the program staged thematic projects in its different rooms. The catalogue for the exhibition, also designed by Sheila de Bretteville, was shaped like a house and contained documentation of the thematic rooms in Womanhouse, as well as texts for each of the rooms conceived by the students and participating artists. The rooms were configured around themes of women’s work, domesticity, and motherhood, offering a critical space for students to stage works around these themes. On the cover of the catalogue, program founders Miriam Shapiro and Judy Chicago sit on the top of the steps leading to Womanhouse.

The Register of Women Artists was another document produced at the Feminist Art Program at CalArts. This list was an attempt to develop a functional resource . The Feminist Art Program built a slide library to collect examples of women’s work and through the slide library, the program also compiled this register of artists. It is a fairly short bibliography of names, but the intent is clear: with a lack of information on women artists, this Register attempted to fill that void in the study of 20th century art for the students in the Feminist Art Program and for wider circulation.

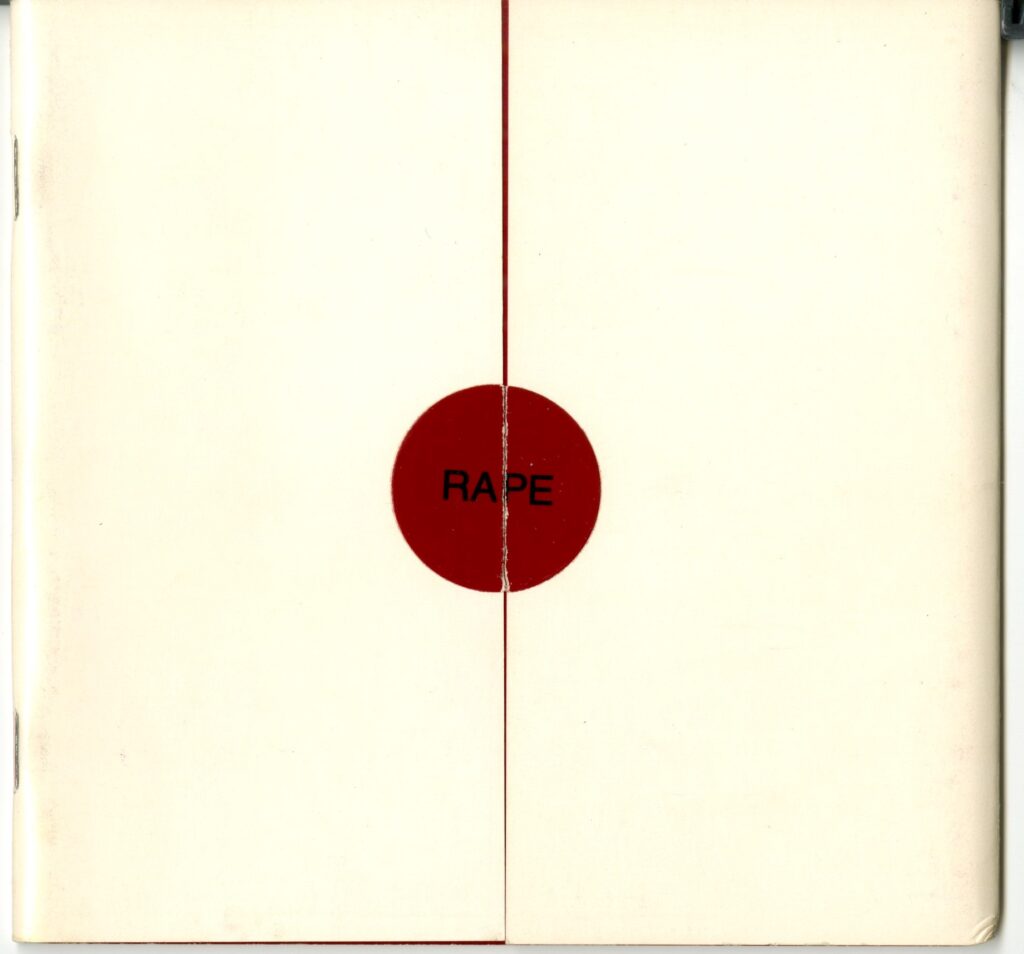

Suzanne Lacy’s earliest work originated from the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State and her time at CalArts. As a CalArts student, she enrolled in the Women’s Design Program founded by Sheila de Bretteville. She also participated in coursework and had a studio alongside the other women in the Feminist Art Program. In 1972, she printed and published her first book Rape is at the graphic studios of the Women’s Design Program. This publication became a defining document of this period of feminist work. In it, Lacy transcribed aspects of the physical and psychological violence toward women in American society. Examples were taken from seminars in which women in the program surfaced personal histories of sexual abuse and violence by men. The small yet impactful booklet provided an outlet to this subject of sexual trauma and created a forum to publicly reckon with this subject. Lacy later reprinted the book for wider circulation in 1976 through the Women’s Graphic Studio at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles. It was exhibited in Suzanne Lacy: We Are Here, which featured Lacy’s books and postcards, several of which were loaned by the SFMOMA Library.

In 1973, a group of women artists and art historians founded Womanspace at an old laundromat at 1107 Venice Boulevard in Los Angeles. Womanspace was a cooperative gallery for feminist art and community that was the first of its kind in Los Angeles. Womanspace staged exhibitions, performance, and film programs, including Suzanne Lacy’s performance Lamb Construction (1973), as well as other community events. It also launched Womanspace Journal, which was published bimonthly for three issues during 1973. The journal promoted the gallery’s programming and included critical pieces about feminist art and ideas and the aspirations of the gallery, written by members of the community. In issue one, photos document the collective work that went into renovating the old laundromat prior to opening, in addition to photos of meetings and group discussions around the planning of Womanspace. The artists at Womanspace also hosted Joan of Art Seminars, a series which provided training to women on how to navigate the art market. The Womanspace gallery relocated to the Woman’s Building upon its founding, as one of many non-profit organizations hosted within.

In 1973, editors Kirsten Grimstad and Susan Rennie traveled over 12,000 miles by car across the United States to document women’s centers and other organizations supporting women’s culture, naming their document the New Women’s Survival Guide. Included in the guide were feminist presses, art organizations, legal advocacy groups, women’s health and wellness centers, and grassroots political organizations. Modeled in format after the Whole Earth Catalog, the New Women’s Survival Guide mapped the explosion of organizing and community building across the United States, detailing issues addressed by the women’s movement and creating an information service for people interested in connecting around specific women’s issues across the country.

One section of the catalogue documented feminist art organizations from around the country, beginning with documentation of the proposed Feminist Studio Workshop in Los Angeles through excerpts and quotes from the workshop’s founders Judy Chicago, Arlene Raven, and Sheila de Bretteville, which were taken from the first promotional booklet created for the program. There is also an excerpt from Judy Chicago’s memoir Through a Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist, later published in 1975, as well as reprinted photos from the Womanhouse project. The organizers of the workshop would subsequently found the Woman’s Building as the site for the Feminist Studio Program in the former home of the Chouinard Art Institute, Los Angeles..

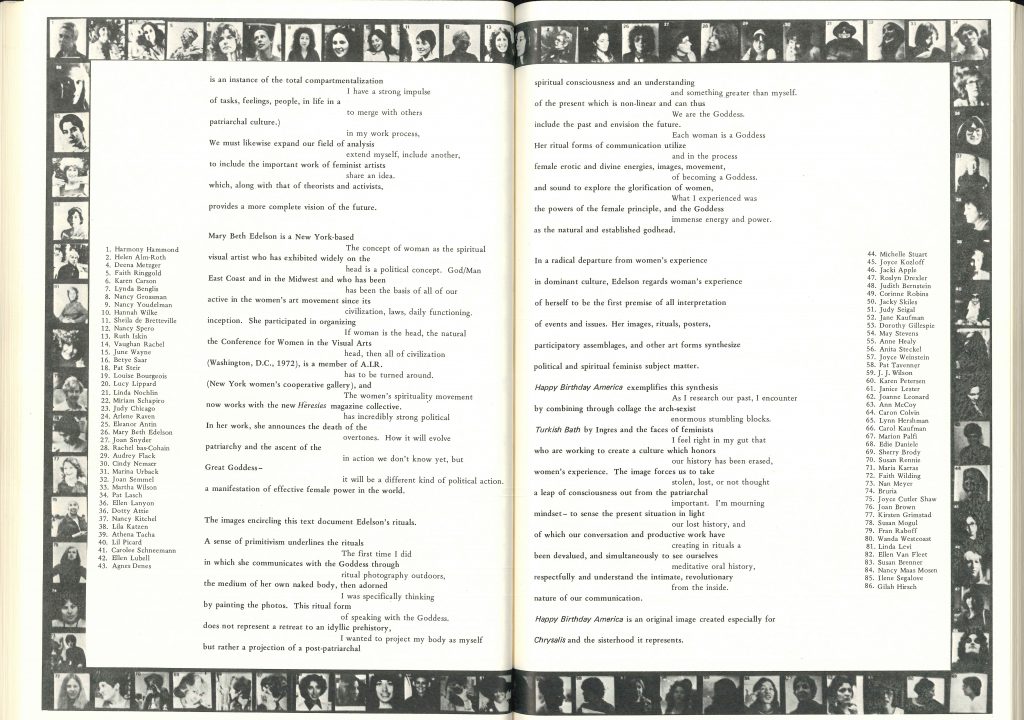

Grimstad and Rennie continued a connection with the Woman’s Building in the subsequent years with the founding of Chrysalis: A Journal of Women’s Culture, in 1977. Chrysalis became one of the active organizations within the Woman’s Building over the course of its run from 1977 to 1980 and a primary site to view the substantial network of artists, writers, theorists, historians, and activists connected to the building. They were joined by Ruth Iskin, former editor of the Womanspace Journal, Sheila de Bretteville, and Arlene Raven as the founding editorial board. Designed by Sheila de Bretteville, the journal and its covers often featured work by notable women artists such as Betye Saar and Eleanor Antin. The first issue of the magazine featured a notable contribution by the artist Mary Beth Edelson with a commissioned work, Happy Birthday America. Alongside an interview with Arlene Raven, Edelson created a portrait of the feminist art community by assembling a large number of photographs of women artists, curators, and art historians, and overlaying these images on a reproduction of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s painting The Turkish Baths. The list of all the women’s names accompanying the work provides an informative chart of the broad network created by women’s projects in contemporary art at that moment. Chrysalis had a run of ten issues from 1977 through 1980, and throughout these issues, the magazine provided a site for various intersecting genres of feminist arts and letters, intermingling and furthering conversations on women’s culture.

From 1969 to 1974, Lucy Lippard organized a series of group exhibitions of conceptual art in different cities, naming each exhibition by the population number of the host city. For these exhibitions, Lippard created catalogues for her “numbers” shows, in which each artist’s contribution and biography were listed on a set of index cards. In 1973, Lippard curated show of twenty-six women conceptual artists that originated at CalArts in the A402 gallery on campus. The show was subsequently titled ca. 7500 for the estimated population of Valencia, CA, where the college was located. It included Adrian Piper, Bernadette Mayer, Christine Koslov, Alice Aycock, Nancy Holt, Eleanor Antin, Agnes Denes, Alice Aycock, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, among others. Lippard’s show was a brief event in which women artists from New York and Europe were introduced to new audiences on the West Coast in the midst of this nascentinteresting moment of feminist arts education at CalArts.

Two other catalogues of student exhibitions were produced during the following years of the Feminist Art Program at CalArts. The first catalogue for the exhibition, Anonymous Was a Woman (from the 1973–1974 academic year), introduced the students working in all the different departments of the program by their medium. The second large section which follows presented an extraordinary collection of letters sent to the students by a large number of women artists and art workers. The letters addressed the idea of what it meant to make art as a woman, or the advice older women artists would give to this class of students (1974–75). These correspondents included an impressive gathering of contemporary artists that responded to the call for letter by the organizers, such as Adrian Piper, Betye Saar, Marcia Tucker, Sheila De Brettevile, Sylvia Sleigh, Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann, Barbara T. Smith, Michelle Stuart, Eleanor Antin, and Lucy Lippard, among many others.

The second catalogue from 1975, Art: A Woman’s Sensibility, similarly was created through an invitation for participating artists to write a letter about their work. In the catalogue’s introduction, Deena Metzger, who at the time was directing the writing program at the Feminist Studio Workshop at the Women’s Building in LA, writes, “A woman’s letter is musing, contemplative, exploratory. It laughs, breaks sentences, interrupts itself, thinks, analyzes, caresses, suggests, responds. It is a conversation. It is revealing. Intimate. A community of women artists writes a letter to another community of women artists who write letters back. What has this to do with art? Everything. And with women’s art? Even more.”

From its founding, the organizing of performance conferences, events and artists’ talks created a hub of activity at the Woman’s Building. Artists from California and elsewhere were invited to participate and they gathered on these occasions to experiment together with new work. Eleanor Antin, Joan Jonas, Yvonne Rainer, Pauline Oliveros, Linda Montano, Bonnie Sherk, Barbara T. Smith, Martha Rosler, Martha Wilson, and Lynn Hershman Lesson are examples of women that participated and performed in the context of these events. A dynamic network of artists’ relationships developed as a result and sustained new work and collaborations among a broadened community of women artists.

The various newspapers, journals, catalogs, artists’ books, flyers and invitation cards highlighted here form part of the collective history of feminist art practices in the west coast of the United States in the 1970s. The publications trace how artists were working together to create new spaces for each other, and the space of these publications remain as a clear site to encounter and engage with the history of the feminist art community and the various strategies for community-building that were deployed. From the SFMOMA Library’s collections of artists’ books and ephemera, these materials are available for researchers now to explore how publishing and the distribution of printed matter was a companion to these feminist artists and helped them create and connect international communities of women artists and art workers.