René Magritte: The Fifth Season is the first exhibition to focus exclusively on the artist’s late career, from the 1940s through the 1960s, a period of remarkable artistic transformation and revitalization. The exhibition is organized into nine thematic galleries exploring the different ways Magritte balanced philosophy and fantasy, irony and conviction, to illuminate the gaps between what we see and what we know. We sat down with exhibition curator Caitlin Haskell and the curatorial team for a roundtable discussion about the show. Four themes emerged: Magritte and Surrealism, Use of Style, Mystery, and Immersive Spaces.

René Magritte, La préméditation (Forethought), 1943; Koons Collection; © Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Magritte and Surrealism

SFMOMA: Let’s start with a basic question. Is this show about Surrealism?

Caitlin Haskell, associate curator of painting and sculpture: You know, that’s not such a basic question—it’s a topic that we could spend a few hours discussing. But one way to answer succinctly is to say that nearly all of the artworks in the show date to a time after Magritte had cut his official ties with Surrealism.

Typically, people think of Surrealism as the work of a group of artists and writers active in Paris in the 1920s, who were concerned with, among other things, questioning cultural habits and interrogating rational thought. But our show picks up after that moment, during World War II, when the realities of the war had caused many of the core practitioners to disband.

Our story really begins with a body of work known as “sunlit surrealism.” It’s invented during the war years, in 1943, and we have both oil paintings and gouaches from this time that are shocking and fantastic and unsettling in the ways that Surrealism can be. And in typical surrealist fashion, Magritte authored a few manifestos and treatises defending “surrealism in the sunshine.” But this was not a direction that was broadly championed, to say the least.

Alex Zivkovic, project research assistant, painting and sculpture: This topic makes me think of a Life magazine interview from 1966 where Magritte is essentially asked the question you posed us, and, I’ll paraphrase his response: I suppose you can call me a Surrealist, because you have to use one word or another, but one should really say that I’m involved with realism. And then he goes on to say that realism usually refers to daily life in the street, but that he’s concerned with realism that includes all of the mystery that is in the real.

CH: It’s a perfect Magritte response: Yes, I’m a Surrealist. But, no, I’m not a Surrealist.

Lily Pearsall, curatorial project manager of painting and sculpture: I would also say it’s good to bear in mind how Magritte’s life spans the twentieth century. He’s born in 1898 and lives until 1967, and the scope of his work really touches on major themes of his time, both in the realm of art and the broader world. His work in the 1920s is tied in with Surrealism in Paris. Magritte’s forties fall in the 1940s, and the work he made then was necessarily art in a time of war. And then the departure we see in his later work is also really about being postwar. He’s an artist working in the early years of Pop—someone that Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg saw in the 1950s and recognized as a kindred spirit.

CH: It is probably also good to point out that many classic elements of Magritte’s imagery reappear in his later works. You’ll see pipes, clouds, bowler hats, paintings dealing with words and images together. But Magritte’s later pictures tend to be brighter and lighter than his surrealist paintings of the 1920s and 1930s — literally, in terms of their color and palette, and also in terms of their mood. I suppose you could say that he takes lessons learned in Surrealism, particularly our readiness to be deceived by representation, and finds a way to turn those insights to our advantage.

René Magritte, La grande famille (The Great Family), 1963; Utsunomiya Museum of Art, Japan; © Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: Banque d'Images, ADAGP / Art Resource, NY

Use of Style

SFMOMA: In Magritte’s “sunlit surrealism” and vache periods of the 1940s — when he adopts the techniques of Impressionism, Expressionism, and Fauvism — is this homage, parody, or something else?

CH: That’s a question we’re still debating. In fact, in the catalogue for the show, we have two essays looking at the sunlit period and the vache together, and one of the authors leans more on the side of them being sincere, and the other reads them more as pastiche or parody.

For me, rather than coming down on one side or the other, I think it’s probably more productive to acknowledge that Magritte was deliberately trying to make paintings that would provoke an unsettled response. He wanted to make paintings that would ride this line of ambiguity, that are maybe even a little disturbing because they are so overtly happy — almost too full of pleasure.

Do I feel that Magritte was genuinely trying to be a latter-day Impressionist, or a latter-day Fauve? No. Both of these moments are pretty clearly rebellions in paint.

AZ: At the same time, there is this sense of hiding behind a respected but outdated style. People will sometimes call the sunlit paintings his Renoir style, and it’s as if Magritte is saying, “What, you don’t like Renoir? What’s objectionable about Renoir?”

LP: It’s also possible to think of Magritte’s use of style at this point as a kind of formal manipulation — a variation in the way that he manipulates scale and cropping or framing in other bodies of work.

We’ve been using the Instagram analogy. It’s almost like he’s applying a filter, saying, “Here’s my composition, and now I’m going to apply Renoir.” And by adding these filters, either the sunlit or the vache, Magritte is provoking the viewer and interrogating their response to both the style and content of these images.

CH: This is probably a good time here to talk about the word vache, which means “cow” in most contexts. But there’s another sense of vache, too, in that vacherie is behaving badly. And, as we’ve been saying, Magritte is playing — he’s being cheeky, but with a serious purpose.

René Magritte, Le mal de mer (Seasickness), 1948; private collection; © Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mystery

SFMOMA: You’ve talked about Magritte’s work as mysterious and enigmatic. In what ways do these images make us question, both the works and our own reality?

AZ: I think about SFMOMA’s Personal Values, which is one of the most gorgeous and painstakingly painted works Magritte made. It’s a deeply evocative painting, and also a bit disconcerting because it pictures familiar things in the world — a match, a comb, a shaving brush, a bar of soap — but it shows them out of scale, and in a room with luminous walls of blue sky and clouds. It could not be painted anymore perfectly, but it uses clarity to develop mystery.

LP: One of my favorite Magritte quotations is “Only thought resembles.” In other words, the only way we understand how an image is connected to an object is through the filter of our experience and imagination — what and how we think and perceive. It’s how images connect to language and thought that is so mysterious and provocative for Magritte.

René Magritte, Les valeurs personnelles (Personal Values), 1952; collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis; © Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Immersive Spaces

SFMOMA: You’ve talked about different fields of view in Magritte’s work, and the use and elimination of framing. Can you tell us about the immersive spaces in the exhibition?

CH: We have two galleries that are especially immersive. One of them, The Enchanted Domain (1953), was designed by Magritte to be immersive. It’s a 360-degree mural that he called a surrealist panorama. The final realized version is more than 200 feet around and integrates many of Magritte’s best known motifs into one continuous cycle. For our presentation, we’re showing oil paintings Magritte made as models for the panorama, which likewise connect end to end and show a continuous story that moves across different canvases.

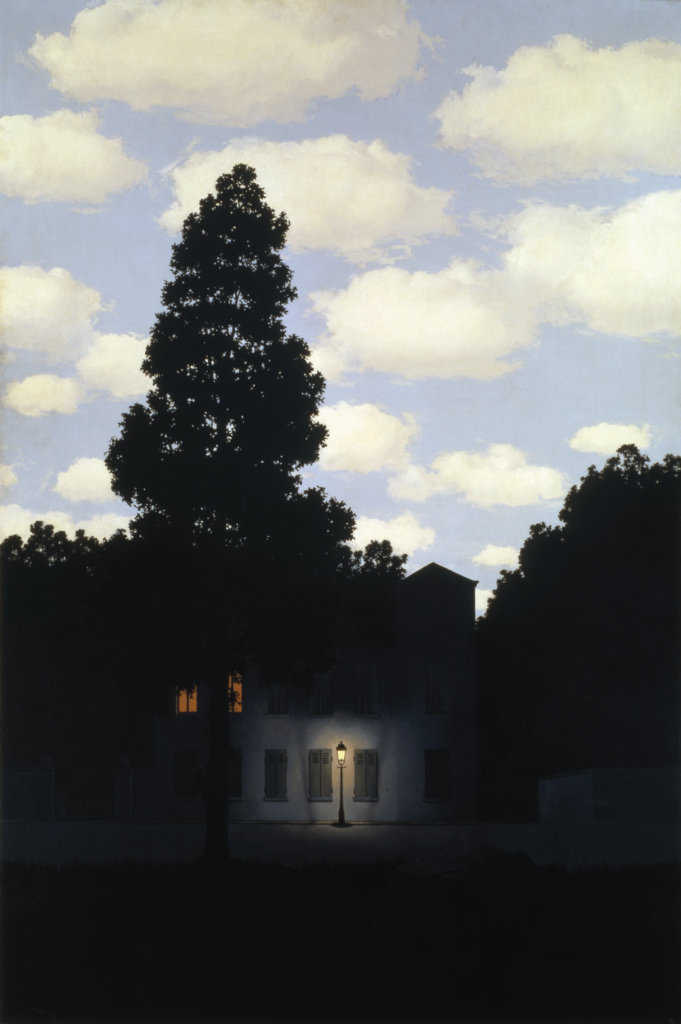

And the other immersive space centers on The Dominion of Light, a series which was not initially intended to be experienced as a whole. Magritte was absolutely captivated by this composition — a nighttime landscape joined with a daytime skyscape — and he created more than a dozen unique variations between 1949 and 1964. Our show brings a full gallery of these paintings together, allowing visitors to see the singularity and the continuity of the series for the first time.

LP: And these immersive galleries are also our way of nodding to Magritte’s play with scale and size throughout his work, and the disorienting nature of changing the relationship between you and your surroundings. So whether it’s a giant comb in the room or maybe a disorienting view out a window — all of these are ways of disrupting our understanding of the connections and divisions between ourselves and the space we occupy.

CH: In a sense, these galleries are spaces where you get to think critically about how reality is constructed. I suppose you could say they’re an invitation to enter into Magritte’s world, and to see your own reality as a place equally permeated by mystery.

René Magritte, L’empire des lumières (The Dominion of Light), 1954; Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice; © Charly Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

René Magritte: The Fifth Season is on view from May 19 through October 28. Get an early look at the exhibition during our Member Preview Days and Party, May 17 and 18.