If you’ve been grooving on the photos of SFMOMA’s building construction and art installations, you may have noticed a particular photographer’s name popping up repeatedly in the credits: Henrik Kam. A longtime San Francisco resident and photographer, Kam has dedicated much of his energies in recent years to documenting the tremendous changes taking place in the local cityscape—both on his own and for clients. He is an avid urban hiker, focusing in particular on the waterfront (“from ballpark to ballpark” is how he puts it), and brings a unique sensibility to his work documenting the new SFMOMA.

SFMOMA: How and when did you get connected with SFMOMA?

Henrik Kam: My work with the museum started in 2008 with documenting the then-new rooftop sculpture garden designed by Mark Jensen Architects. That job was commissioned in the sense that I suggested that it be done, and then I negotiated some money to pay for my expenses. It served as the launch pad for my long-running engagement with the museum.

Photo: Henrik Kam

I’ve since done a similar project for SFJAZZ, when they built their new building over in Hayes Valley. And currently a much smaller project for Saint Francis Hospital in the Tenderloin. I go in and look for something artistic, something designed, in the chaos of a work site and try to frame it so it makes visual sense. I’m less interested in the process itself than the look of it.

SFMOMA: I’m intrigued to hear you say that you’re not so interested in process. It’s somewhat ironic, because documenting the process is presumably what the client is buying, right?

HK: I suppose I’m interested in my take on the process. I’m not so interested in what the engineer or the architect or the contractor perceives.

“Henrik’s incredible artistic and creative visual responses and documentation of the new Snøhetta building have made me see the process in a more expansive way. Now, when I look at the new building, I see it from his artistic perspective and keen eye.”

SFMOMA: What exactly attracts you in a space being worked on, or in transition?

HK: Some of my favorite shots show a space completely filled up: when the visuals are layered, things break the frame, there are lots of shadows, and it’s difficult to see what’s what.

Photo: Henrik Kam

SFMOMA: Now that the new museum building itself is mostly finished, what are you shooting?

HK: I’ve been coming around every couple of days to photograph the artworks being installed, or sometimes just the stacked-up crates—the preparation for the art to come out and be hung. The crew putting things up is like a ballet. Everybody’s very quiet, they just take a corner and do their thing. And I sort of dance around and snap away. No tripod; it’s very loose.

SFMOMA: So what’s your preferred mode? Working in a clean if slightly disarrayed gallery space, or being in the midst of crazy, dirty, chaotic construction?

HK: It’s so different. When I photograph a construction site, there is more to surprise you. But I have to wear a hard hat, safety glasses, gloves, and boots, and all that stuff impedes my vision. I also like photographing when it’s all done, because it’s clean and wonderful.

I think my favorite period during the construction was the steel. It’s amazing to see how these huge buildings get made. It’s just four people putting them up: two guys on the ground who hook the steel onto the crane, and two guys up above who bolt it in place. I hadn’t previously thought about it much, and I got to talk to the guys. I think it’s the most athletic and impressive job on the work site. And when they’re done, they move on to the next building. And then they can tell their kids as they drive around, “I built that building. And I built that building, too.”

“Henrik’s found moments of incredible beauty every time he’s visited the site, both during construction and now that the building is almost complete. And he’s captured the many people who have helped bring it into being. His curiosity and affection for the building and the construction process are so evident when you look at his pictures.”

Photo: Henrik Kam

SFMOMA: Do you get a little thrill at having all that access?

HK: Yes, absolutely. I’m the only one on the site who’s not really supposed to be there, yet there I am.

SFMOMA: It’s like an untouched snowfield.

HK: And you know what’s really exciting, too, is to be in the building as it goes up and look at the city around, because those are new views that nobody has ever seen before. Vantage points that have been newly invented.

SFMOMA: What are some of the personal projects you’ve been working on lately?

HK: Recently I made two trips to Poughkeepsie, New York, to make a photographic study of the many buildings and vast grounds of the long-abandoned and rather haunted psychiatric hospital there. I showed six prints at Gallery 60six in San Francisco last fall. Long-term, I’ve been documenting the interiors of disused industrial buildings, many of them down at the waterfront, for instance in and around Pier 70 and Hunters Point. My focus is west of Third Street, from (the former) Candlestick to AT&T Park. Ballpark to ballpark.

While I’m there, I’ve begun picking things up. For instance work gloves, because I am really interested in the fact that this used to be a working waterfront, where a lot of manual labor took place. I selected forty gloves and photographed them for a project I call Workforce: Eight Hours a Day, Five Days a Week. I carefully brought the gloves into the studio, put them on a piece of black leather, and lit them so they have a three-dimensional look.

SFMOMA: In the pictures, they almost look like casts of gloves.

HK: They do, don’t they? They have that local contrast that really pops. I preserved all the debris stuck to them. The flattened ones have been run over by trucks.

SFMOMA: What else have you discovered by looking down?

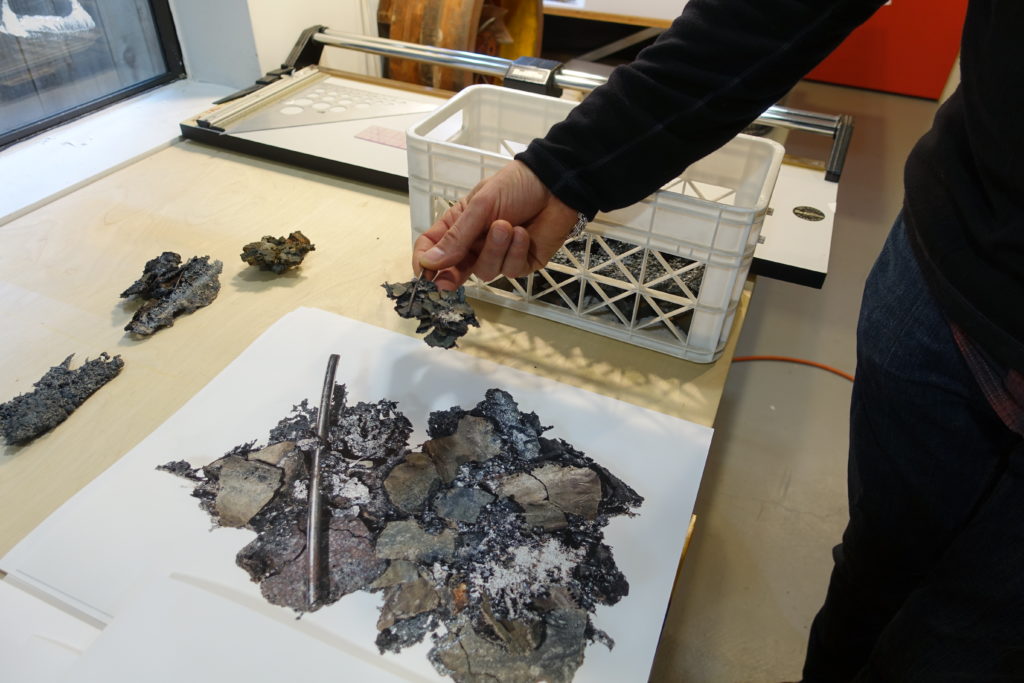

HK: At SFMOMA, when they were welding the steel, there were all these drippings. I was in there gathering them before they got swept away, because I thought they were jewel-like. Look at the colors.

SFMOMA: It looks like something Velvet da Vinci would sell.

HK: Unexpected beauty is what I look for. Be it hidden inside a material, or the juxtaposition of furniture versus light, or abandoned buildings.

SFMOMA: How did you arrive in San Francisco originally?

HK: I was born and spent my early years in Denmark, then came to the States with my family when my dad, who worked for Lufthansa, was transferred to Los Angeles. Then after eight years he was transferred to Nairobi, but by that time I had finished college at Art Center College of Design and stayed in California. I came up to San Francisco in the early 1980s, and for years had a studio in the American Can building on Third Street, working with graphic designers and architects and magazines.

In 1995 my wife Donna and I decided to close everything down, rent the house out, and travel for a year. I wanted to re-inspire my photography by getting out of the studio; I was stuck in a dark studio all day, and that’s not what I had set out to do as a photographer. We traveled through Southeast Asia, Europe, Nepal, and Turkey. When we returned I opened another studio South of Market that I kept until the dot-com bubble tripled our rent in 2001. And then I built out our garage/basement at this house, and I’ve been working here ever since.

SFMOMA: There’s so much in the news and cultural discourse about artists getting pushed out of the city, but here you are, a successful long-standing San Francisco artist. And interestingly, much of your work involves documenting the changes. You’re perfectly positioned to perceive that evolution and even take advantage of it.

HK: I see the changes pushing ahead, unabashed. It’s unbelievable what’s going on down around SFMOMA with the Transbay Terminal. When we first bought this house, it was at the edge of an industrial wasteland. Now it’s all residential.

When I began my explorations at Hunters Point, I immediately thought, this area is so ready to be programmed into buildings that could benefit cultural life. But there’s just never the money until there’s a commercial interest. Now Mission Bay and UCSF are pushing the development down this way.

SFMOMA: And you’re teasing out and revealing the beauty in these projects, making art of them. Your clients must appreciate that approach.

HK: I don’t editorialize too much. I do try to juxtapose what’s going on with what was there before, evidencing it. Walking in the footsteps of Janet Delaney. Seeing how development has accelerated, and how much the urban landscape has changed, is mesmerizing. It’s just happening so quickly.