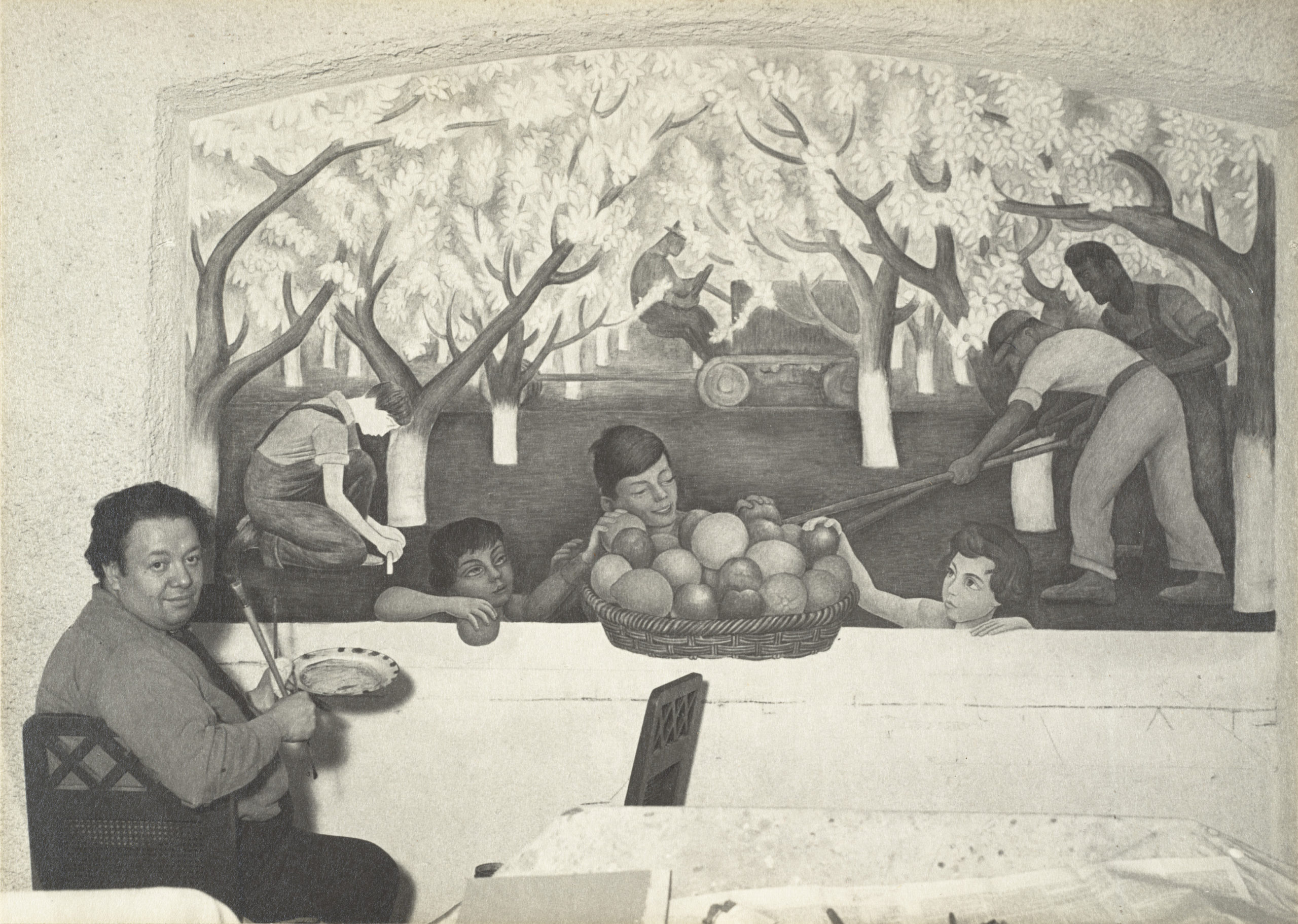

Ansel Adams, Diego Rivera Painting the Fresco “Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees [formerly at Sigmund Stern House, Atherton, California], 1930–31; collection SFMOMA, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender; © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

In November 1930, Diego Rivera swept into San Francisco’s railroad station for the first time. It was the artist’s debut in California, and the Bay Area was his West Coast landing pad. In a revealing photo of his arrival by Ansel Adams, Rivera is flanked by two San Franciscans who encouraged his trip from Mexico City: sculptor Ralph Stackpole, who’d long sung Rivera’s praises across the Bay, and Albert Bender, an art collector and ardent Rivera supporter who would later donate several of the painter’s works to SFMOMA’s collection.

It was a triumphant arrival for Rivera, who was set to paint his first U.S. murals on the trip. While the artist had already achieved an international reputation for his monumental, politically engaged frescoes spreading across Mexico City’s public buildings, he’d yet to realize a civic mural abroad. (A 1927 commission for Moscow’s Red Army building never came to fruition.) So why did San Francisco emerge as the first site outside of Mexico to host Rivera’s frescoes? Why not until 1930? And what forces converged to finally make it happen?

Some of it, of course, came down to timing—Rivera was busy with Mexico City commissions and a trip to Moscow in the late 1920s. But much can also be attributed to a group of Bay Area residents who fought long and hard to bring Rivera and his mastery to their city. The painter’s first Bay Area advocates were fellow artists who’d begun to admire his work from afar, in the early 1920s, and actualized their interest on a trip to Mexico City in 1926. As explored in an in-depth catalogue essay by Maria Castro, SFMOMA’s Assistant Curator of Painting and Sculpture who assisted with organizing Diego Rivera’s America, sculptor Ralph Stackpole, painter Raymond Boynton, and painter Lucretia Van Horn, among others, all traveled to observe Rivera at work that year, with Van Horn even assisting Rivera and sitting for a portrait in his studio.

The group was so enamored with Rivera’s sprawling murals and their bold depiction of everyday life and labor that they began spreading word to their friends at home. Boynton, in particular, “admired Rivera for his ability to create figures that conveyed powerfully symbolic, universal messages, yet were easily recognizable and familiar to contemporary audiences,” writes Castro. As further proof of Rivera’s virtuosity, they carted his drawings, paintings, and photos of his murals back from their travels, too, to share with influential collectors like Bender and William Gerstle. Bender, known for adventurous tastes, was particularly effective in introducing his powerful friends to Rivera’s work. By late 1926, he’d also invited Rivera to visit the Bay Area, setting into motion a nearly four-year-long attempt to bring the artist north.

But when it came to getting Rivera to San Francisco, delays abounded: fresco commissions in Mexico, a trip to Moscow, visa troubles spurred by Rivera’s political activism and tense U.S.-Mexico relations, and general trouble securing San Francisco walls (and an artist fee) large and prominent enough to match Rivera’s work. Finally, after much coordination between Bender, Gerstle, San Francisco architect Timothy Pflueger, and even Dwight Morrow, the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, they convinced Rivera of the journey. The carrot they dangled: a mural in the towering stairwell of the freshly minted Pacific Stock Exchange building, designed by Pflueger.

Finally, in November 1930, after a long train ride, Rivera arrived in San Francisco with Frida Kahlo. By December, he’d completed designs for Allegory of California, the spellbinding fresco detailing California industry and labor at the Stock Exchange, and would go on to complete two additional murals the following spring: Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees (1931), a piece at the home of patrons Sigmund and Rosalie Stern in Atherton, and a substantial fresco at the California School of Fine Arts (later, the San Francisco Art Institute) called The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City (1931).

The three frescoes boldly fused depictions of art, labor, and life of California, while simultaneously projecting Rivera’s own distinct style—born of a distinctly Mexican experience—into the everyday lives of San Franciscans. Perhaps most significantly, the murals went on to inspire a flood of public art across the city by early 20th century artists like Anton Refreiger, José Moya del Pino, Jane Berlandina, and Esther Bruton, whose influence is still felt in the Bay today. In San Francisco, Castro writes, “Rivera shaped the artistic landscape of the city. Though mural painting had long been an important tradition there, Rivera’s presence catalyzed a widespread embrace of muralism—and the fresco technique in particular—as a key medium of modern art.”

Read more on Rivera’s first trip to San Francisco in the essay “Diego Rivera’s New American Art: San Francisco, 1930-31″ by Maria Castro, included in the exhibition catalogue Diego Rivera’s America.