Responsive displays are increasingly used in public spaces, but integrating this type of technology into the public spaces of a visual arts organization is more difficult than you might think. SFMOMA’s recent transformation and expansion gave us an opportunity to explore this technology in the museum context.

In advance of SFMOMA’s 2016 reopening, we developed a set of three large digital screen arrays to be installed in the two main atria of the museum—a project we intentionally named Story Screens. The Story Screens use a set of Microsoft Kinect cameras to create a depth map of people’s movements in front of them. This map is fed into the application that powers the screens, and can be used to trigger new, or alter existing, content on the Story Screens. We use the movement feed to trigger content or change the density of the information onscreen. We can also supply the data feed to the artists and designers we commission to make work for the Story Screens.

At the outset, we asked ourselves a few key questions:

- How do we make the screen work aesthetically within the space, keeping in mind that the technology is meant to complement the museum, not compete with it?

- How do we hide the hardware without compromising its performance?

- And can we do things in a way that is replicable for other institutions interested in using this kind of technology in similar ways?

The result was a focused design that balanced aesthetics and performance. This article takes a look at how we got there.

Testing the Kinect Camera

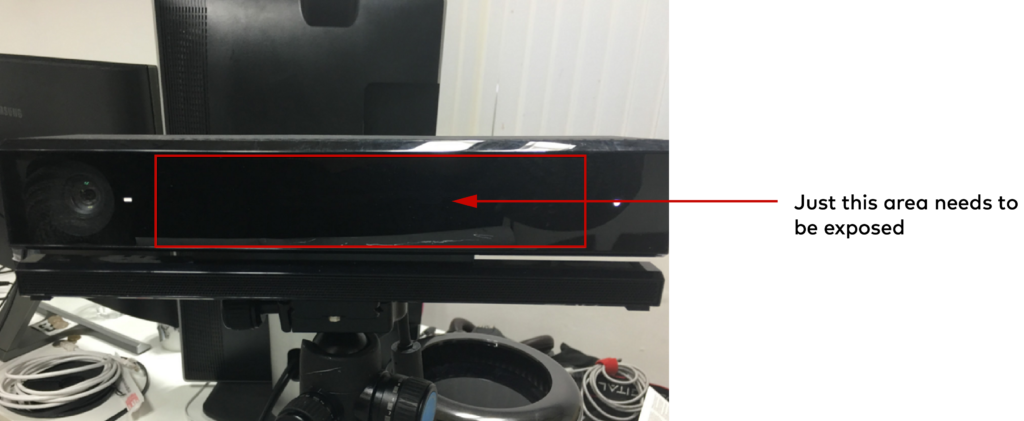

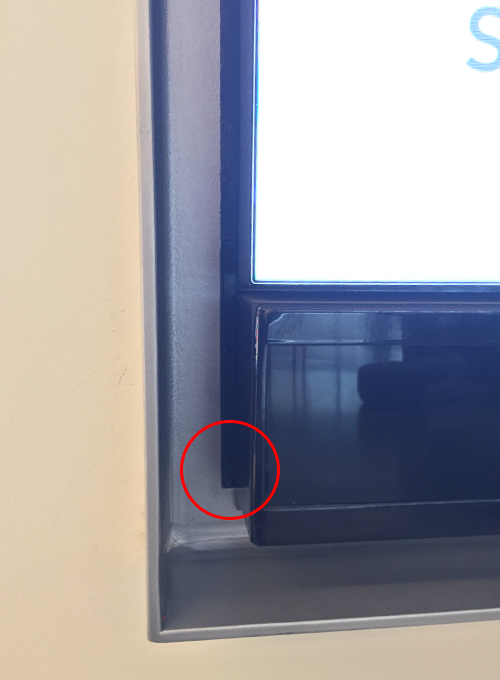

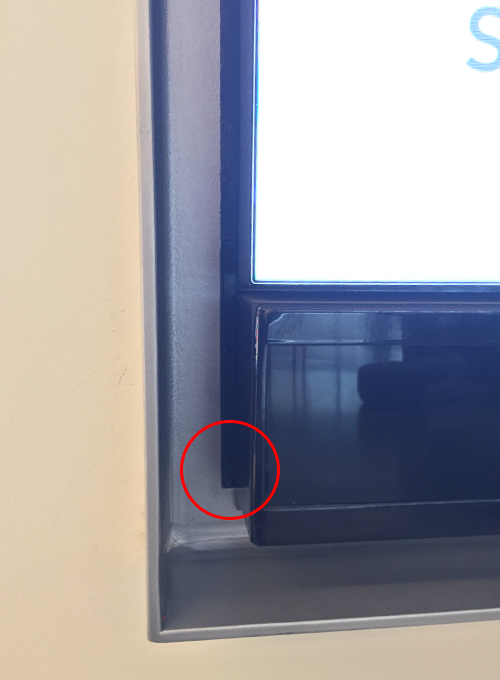

One of the first issues we addressed was how to hide the cameras without compromising their performance. To accomplish this, we designed a metal camera housing with an acrylic face, effectively hiding the cameras while allowing them to receive a data feed.

Window needed for camera

After conducting a series of infrared (IR) transparency tests, we realized the thickness of the acrylic had an effect on the signal received by the cameras, even though the acrylic was transparent. So, we conducted additional tests using different acrylics with a variety of thicknesses. We had to balance two issues: the acrylic had to be thick enough to prevent buckling as it spanned the length of the camera housing yet thin enough to minimize obstruction of the data feed, which would cause attenuation of the image. After these tests, we decided the best option was 3/32 inch.

Infrared Testing Results

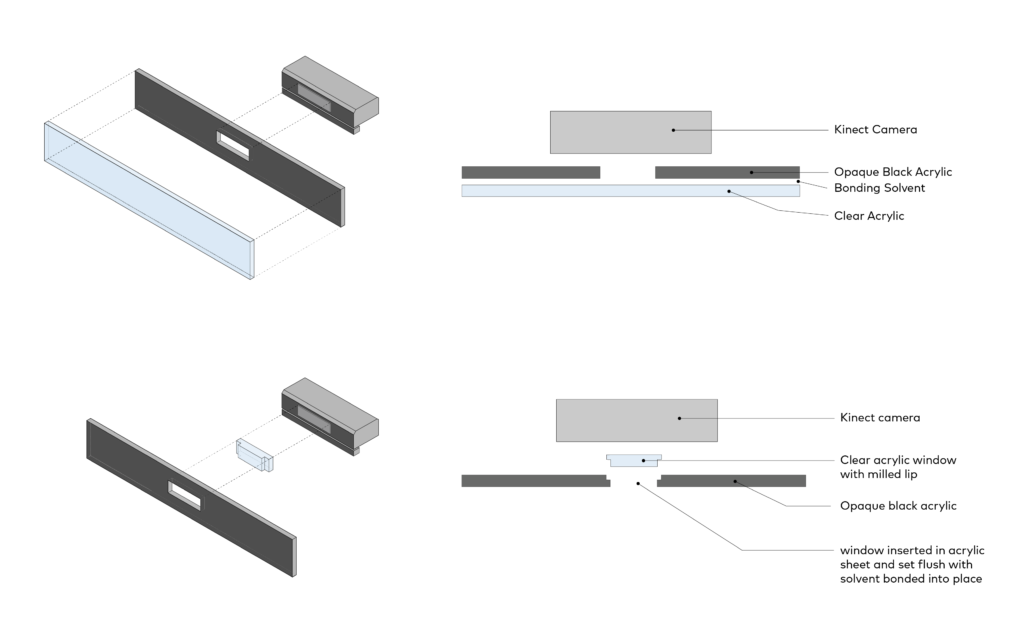

Having a seamless appearance was a defining factor of the design. Clear acrylic would expose the equipment inside the housing, which would not fit aesthetically within the space of the atrium. But when we tested black acrylic sheets — in the hope that we could keep the cameras entirely out of sight — there was significant degradation of the signal relative to the clear acrylic. This led to the idea of having a clear aperture in front of the Kinect camera face, leaving the rest of the acrylic black to cover the other components — a solution that incorporated both ideas.

Testing various applications of acrylic. Application 1 (top) caused a gap in between the face of the Kinect and the face of the acrylic, and it was possible that the solvent would degrade over time. Application 2 (bottom) caused shadows across the aperture.

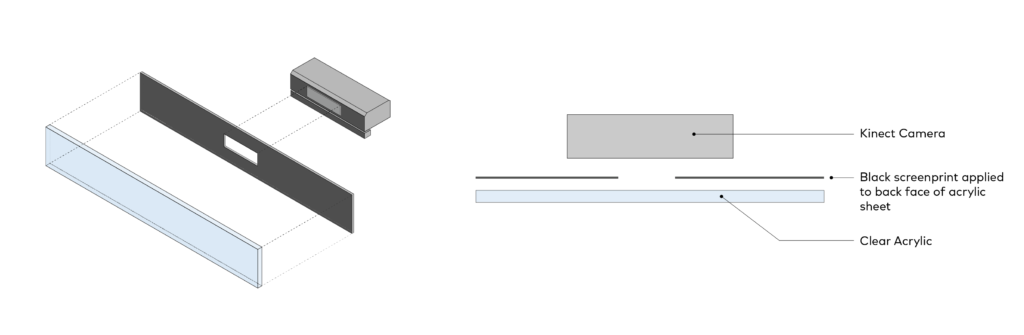

After testing many options, we found a solution by screenprinting a sheet of clear acrylic with black paint, having taped off an area for the aperture so it remained clear. This application gave us the opacity we needed to hide the equipment inside the camera housing while ensuring that the cameras performed well.

Final acrylic assembly

Overall Design

It was imperative to incorporate the technology in a way that was aesthetically consistent with its surrounding context. We paid close attention to the architectural design in each atrium, and translated its aesthetics into the assembly design.

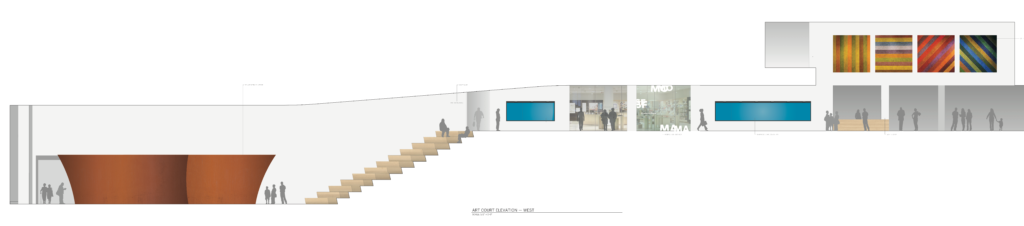

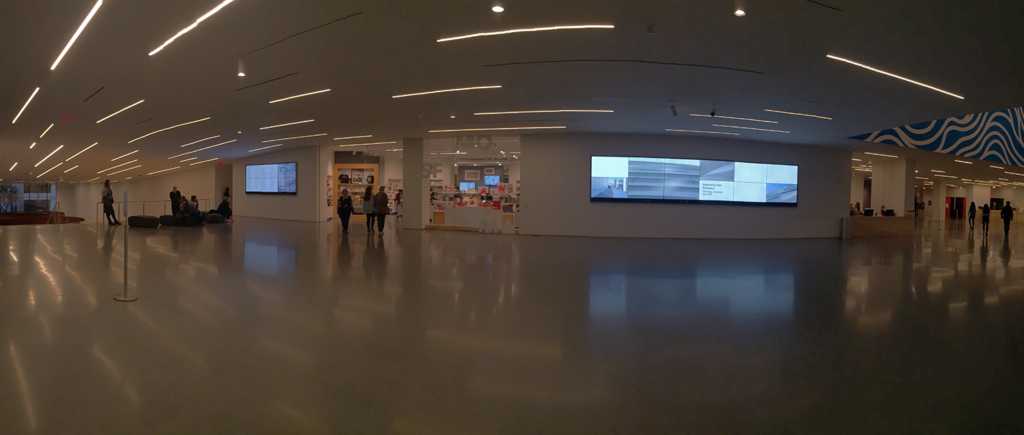

Story screens in Schwab Hall

To echo the aesthetic of the space, we focused on clean, elegant lines, minimized seams in the camera housing and the outside frame, and recessed the assembly into the wall to keep a low profile. We also aligned the screen arrays with key architectural elements, such as elevators and other signage, to create a visual datum line throughout the space.

Digital signage throughout Schwab Hall

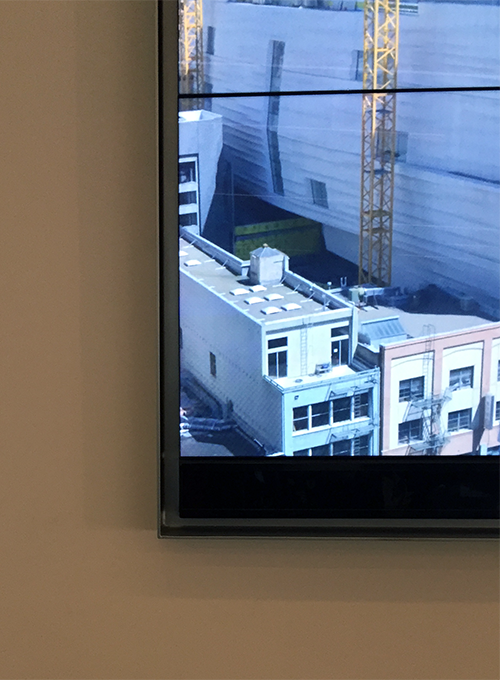

From the pattern on the wood panels to the striped granite walls, Haas Atrium provided a strong geometric grid with a structured rhythm. We used this regimented pattern throughout the design of the Story Screens to correspond to that rhythm and blend into the atrium.

Story screen array in Haas Atrium

Designing the Camera Housing

To attain a seamless display, we designed a housing from a single piece of bent aluminum with minimized joints, color-matching the powder coat finish of the housing and the surrounding frame to the adjacent materials. We also paid attention to the transition between materials to maintain clean visual lines and avoid abrupt changes.

Since the housing had to span a long distance — up to 24 feet in the case of the array in Schwab Hall — we couldn’t fabricate a single camera box for the entire display. Instead we designed individual camera boxes and aligned the edges with the bezel of the digital screens above, maintaining the pattern already established in the assembly.

Detail view of screen housing with black painted line visible

When seen head-on, the black line disappears

Detail view of screen housing with black painted line visible

When seen head-on, the black line disappears

Functionally, the casing needed to allow accessibility for cleaning and hardware maintenance. This was achieved through a set of hidden fasteners that allowed the housing to be removed when necessary without disrupting the clean aesthetic when it was in place.

Kinect camera and wall mount

The Outcome

After the careful selection of materials in tandem with rigorous testing, the Kinect cameras are now a part of the museum landscape. The right elements are hidden and keep visitors focused on the experience, not the technological apparatus. Finding the right solution required a thoughtful approach, one that was mindful of the complexities that come with adding new technology and hardware into the museum context.

One of the big questions we continued to ask ourselves throughout the project was: “Will this technology be perceived as a seamless element, or will people notice the cameras and get creeped out?” Shortly after the installation was complete we walked through these spaces with our curator of Media Arts. When he didn’t notice the hidden cameras, we felt like we had succeeded.

In the end, it was all about finding the right balance. This project allowed us to rethink how to use technology in our public spaces as a way to activate them. Our Story Screens now offer new modes of storytelling in ways that were previously unexpected in a museum. We are excited to see how we can continue to develop and expand this technology by pushing it in new directions.