Take One: Washington, D.C., 2003

First, a story about blackness, desire, and cars:

I attended my first Black Pride in 2003 during my sophomore year at Virginia Commonwealth University located in Richmond, VA, just two hours outside of Washington, D.C. At the time, Washington, D.C. and Atlanta, GA, were considered black gay meccas because of their proportionately large black gay populations. For me, Black Prides turned city spaces into fantasies. I was raised in a house where my sexuality was to stay a secret, forever. When I was sixteen years old my parents found some gay pornography I had mistakenly left in sight and brought it to my attention. I had a panic attack. My mother, the sweetest woman I knew, in an instant directed all her vitriol at me. I said someone planted the picture on me. An obvious lie but my parents went with it, but not before making sure to tell me that if that picture ever got out it would be an embarrassment to the family. In other words, if it were ever revealed that I was gay a great shame would cover the Batts household. Somehow my parents let me skip church service the next day. While they were away at church I cut up pictures of naked men and flushed them down the toilet. In 2003, on the streets of the nation’s capital, surrounded by black gay men, I thought my unmentionable dreams were coming true.

. . .

I met him on the internet when I was a junior in college. He said he worked in some security field but wouldn’t give me his job title. After some convincing by me, he agreed to meet at a Starbucks. I was twenty and still a bit ignorant. He was tall, dark skin, with a slim muscular build. He was one of the harder, “masculine” types in Richmond, VA. The only kind of men I used to like. Once, in excitement, I ran across the wide streets of Richmond to meet him. He told me men my height shouldn’t run. I quickly tempered my excitement. My father was forty-eight years old when I was born, shook Martin Luther King Jr’s hand, and participated in the sit-ins. When I was in middle school, I approached him in tears because my classmates were calling me gay. He told me to stop bending my wrists. I listened. Black Pride was an escape from those I, or my body, had to answer to. I remember bringing my tightest clothes in the brightest colors. When I got a call from the boy from Richmond I was excited to hear he was in D.C. too, but I was also a little frightened about his reaction if he saw me in such tight jeans. We agreed to see each other at the club that night.

That night I was full of excitement. I still remember what I was wearing, a tight black T-shirt with pink lettering. It said something in Spanish, all I remember is the word “leche.” I paired it with some matching black and pink Converse-brand sneakers and some cheap pink-tinted sunglasses I’d bought earlier that day from a kiosk in the mall. That night I was going to a party, basically blind, in order to wear these cute sunglasses in a dark club and dance with the boy I wanted. I was twenty years old so I drank as much liquor as I could handle before I left the hotel. One of my best friends and I were in the lobby, drunk, looking for someone to drive us to the club because our older friends had fallen asleep. While downstairs a group of older African Americans donning kente cloth stopped us and asked if either one of us knew the name of the man who organized the March on Washington. Somehow, in my intoxicated state, I quickly answered “Bayard Rustin, but he was not given recognition because he was gay.” The woman who asked the question said to her friends, “I knew he would know.” As edgy as I think I look, the nerd somehow always shows.

My friend and I piled into a compact car full of kind strangers. It was packed so tight I had to sit on the lap of a man I did not know and could hardly see. I had this intense anticipation to get to the club and see the boy from Richmond. The music in the car was loud but the police sirens were even louder. The driver of our small car pulled over. Three other police vehicles showed up and surrounded us while their sirens blared and bright red, white, and blue lights flashed. Over a loudspeaker, a police officer told us all to put our hands up. For a second, all of the black gay men / all of the black men in the car thought we might die. That night, the officer gave the driver of the vehicle a citation and we drove back to the hotel. We never made it to the club. I didn’t get to see the boy from Richmond. In fact, I never saw him again. I always thought he was a cop.

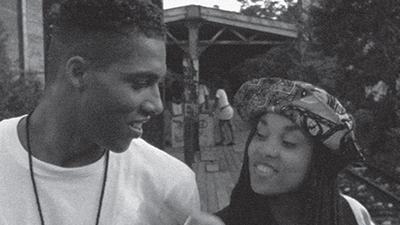

Leslie Harris, Just Another Girl on the I.R.T., 1992 (still)

Take Two: “You got a fast car. I want a ticket to anywhere.”

“In her mid-twenties to thirties, my mother was humble, funky, and fly. She liked wigs, dressing up, and dudes who could sing, drove sweet cars, and wore fly suits and gators. She was a Sundayschool teacher.”

–L.H. Stallings, Funk the Erotic: Transaesthetics and Black Sexual Cultures*

“Back seat of my jeep, let’s swing an episode”

–LL Cool J, “Back Seat”

The thing about black cult film classic Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. that most often seems to capture the attention of viewers is lead character Chantel’s love of boys with Jeeps. I recently searched for the film on Twitter and people can’t get over the hilarity of how Chantel’s tough “Brooklyn girl” exterior consistently falls to the whims of boys sittin’ on chrome. I can remember this early 1990s love of Jeeps. My lower middle class family spent a month picking out the perfect Jeep Grand Cherokee, only to have it stolen directly in front of church during Bible study the night it was purchased. I can also understand the desire for a man with a reliable car in a city where the rent continues to rise, whether it’s Brooklyn or the Bay area. Some of us smile at boys with Jeeps, and some of us tap “like” on every tech bro’s profile we see on Tinder (even if they never “like” back). We all thirst for security.

Just Another Girl begins in some version of Brooklyn, New York, 1993, with (spoiler alert) Chantel’s just delivered baby being disposed of, at her request, in a black trash bag (the baby will soon be rescued). The blue lit tenements that background this scene, the ambulance that basically refuses to visit Chantel, and the baby crying in a trash bag foreground the city’s disinvestment in black futures and, in hindsight, foreshadows the coming of gentrification. Could it be said that the film also represents the making of black sexual desire under these circumstances?

The next scene is a flashback to simpler times. We find Chantel at a subway station cruising a cute dark brown black boy with flawless skin and a short curly (processed?) box haircut. His name is Jerry. He says he’s a model. Chantel plays him — “Like Tom & Jerry?” she says — until he reveals that he has a car. “Well, how you doin’?” she replies with a charming high-femme smile, extending her hand, “My name is Chantel.” There’s this short close-up of Chantel’s red fingernails inserting a token into the subway terminal to get to the train that will take her to her next destination, her part-time job. The shot signals an erotic intensity coursing through the entire film. Chantel doesn’t just enter subway stations for economic efficiency, she’s interested in the potential of the unknown destination. Whether Chantel is paying for the train or a chance to flirt with models will always be questionable. Her desires always seem to waver, undecidedly, between a need for sustenance — in an environment that continually signals its disinterest in where she might land — and another need to be anywhere better than here and now. Her world’s lack of concern for her (well)being leads her to choose (or subjects her to) a fugitive, indecipherable, and sometimes frustrating (for the viewer) movement through the city. The film’s title in its reference to “the I.R.T.” aka the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, marks Chantel’s desire for mobility. A mobility given many names throughout the film, ranging from the more immediate “Jeep” to the futural “college” and many points in between. But in naming her Just Another Girl on a train in New York, Harris half-jokingly gestures to Chantel’s “fungibility.” Chantel is undoubtedly unlike any other girl. Through actress Ariyan A. Johnson and Harris’s creativity, Chantel bears a personality, audacity, vibrant style, and overall way of moving through the world — slicing through space with the movement of her hands, for instance — that make her an unparalleled individual. But it must also be remembered that Chantel, as a character, is a production — a cypher through which audiences project their understandings of black urban teenage women or come to “learn” about them. Which is why I find Just Another Girl to be a useful filmic product worth revisiting in a moment where we see anew a political and cultural divestment from the lives of cis and trans black women.

Harris takes what I believe to be a profound risk in foregrounding her black woman lead’s capitalist desires. Chantel does a number of things throughout the film that IRL would get a black woman labeled a gold digger. It is by wading through the murky and simply unfair waters of stereotype (not avoiding it or trying to get around it) that Harris gives us space to reconsider black women’s sexual desires, as articulated within capitalism, with humane insight. Harris’s artistic decisions resonate with the work of master painter Kerry James Marshall who centers very dark black figures in his painting. A viewer may deem these images completely denigrating, if, Marshall argues they “assume the idea of blackness as being somehow negative.” Marshall attempts to avoid the call to create positive imagery of black personhood (in order to combat a history of imagistic denigration) because in his view this just creates another stereotype, lacking in complexity. His paintings then force the viewer to consider the making of the black figure in representation as a process that both painter and viewer (black, white, or otherwise) are complicit in. Just Another Girl asks viewers to consider their reactions to the questionable (simply because they’re presented by the distance provided by visual representation) actions of a young black woman with sexual and material desires that collide under American racialized capitalism. How you judge her actions should make you consider the mutable ways in which “the idea of blackness” and womanness in conjunction are assumed to be “somehow negative.”

It is past time to consider the actions of Chantel and her friends as modes of experimentation with the tools of pleasure in order to enact an erotic elsewhere. Even as these characters continually find themselves in the same place, the projects. Their representation allow for what scholar L.H. Stallings refers to as the fomenting of “potential antiwork politics and postwork imaginations.” When Chantel “breaks the fourth wall,” looks directly into the camera, puts her hands on her hips, and says “I don’t let nobody mess with me and I do what I want, when I want,” it’s an obvious foreshadowing of a coming hindrance to her mobility. Mind you, even in this moment of Chantel defiantly claiming her autonomy, she is about to walk into a job she does not want (one of two, she also has to regularly babysit her two little brothers). No one can do what they want, when they want. Few can even decipher what they truly desire. But what is it for a viewer to want and desire a world where Chantel, in particular, knows and could have everything she wants?

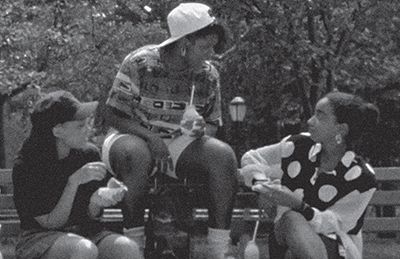

Leslie Harris, Just Another Girl on the I.R.T., 1992 (still)

Take Three: “…you can’t get pregnant.”

Grief is not apparel.

Not like a dress, a wig

or my sister’s high-heeled shoes.

It is darker than the man I love

who in my fantasies comes for me

in a silver, six-cylinder chariot.

I walk the waterfront/curbsides

in my sister’s high-heeled shoes.

Dreaming of him, his name

still unknown to my tongue.

While I wait for my prince to come,

from every other man I demand pay

for my kisses…– Essex Hemphill, “HOMOCIDE: For Ronald Gibson”*

In the final act of Just Another Girl, Chantel becomes pregnant by a boy, with a jeep. This may be read as the director’s afterschool television special public service announcement, warning black women about the dangers of consumerism. In the end, Harris wraps up the film with Chantel pleased with her future. It’s not as idyllic as she’d hoped — a baby and community college instead of a four-year institution, parties with boys, and eventually med school — but she’s happy to be surviving through it all. While Harris can be commended for asking her audience to honor the life of a working class black woman whose situation would often get her labeled “just another statistic,” I want to consider not only where Chantel ends up but her journey there.

In what seems to be a teenage take on the classic scene of black women’s talk in a living room from Spike Lee’s earlier Jungle Fever (1991), Chantel, her best friend Natete, and their friend Lavonica commence to discussing sex and the ever-looming threat of pregnancy. Natete reveals she has been taking her “sister’s birth control pills just in case” she finds the “real man” she hopes to meet at Lavonica’s coming birthday party. Chantel responds, “What?! Natete, what did I tell you about that? Yo, you supposed to have your own prescription for that. Watch, you’re going to get sick.”

Natete: No I’m not going to get sick…I’m going to be ready for Saturday night.

Lavonica: What are you crazy? What’s the problem

with rubbers? What’s so hard about that?

Natete: Most guys don’t like using them things. I don’t even like the way it feels.

Chantel: Mmm Hmm. Word.

Lavonica: I don’t know with AIDS going around…

Natete: Yeah, but none of our friends use rubbers and nobody likes the way it feels.

Lavonica: Yo, don’t you care if you die?

Natete: Look, I’m going to die sooner or later and before I die I want to know what it’s like to feel a real man inside of me. Not some old piece of plastic. Besides the only way you can get it, is if you gay or a intravenous drug user. So chill, because I ain’t fuckin around with nobody like that.

Lavonica: I don’t know. You don’t know where he’s been.

Chantel: Mmm Hmm. That’s right.

Natete: Lavonica chill… You watching too much 20/20, and you reading too much Enquirer. You can’t be afraid of everything…

In this conversation, Natete is wrong about much. Past trafficking in a homophobia also present in the reminiscent scene from Lee’s Jungle Fever, Natete goes on to claim that “If you take a bottle of soda, and you shake it up, and you shoot it up your pussy, then you won’t get pregnant.” I’m more interested in thinking about Natete’s comments on condom use than clarifying the relative truth or falsity of her many claims about sex and safety. In certain queer theoretical circles sexual risk has recently been parsed for its radical potential; gay men’s barebacking, raw sex, and bugchasing (purposeful HIV transmission between consenting serodiscordant partners) is read by scholars to be a potentially radical move, rejecting the normalizing mandates of homonormativity (including safe sex and monogamous same-sex marriage) that seek recognition from a state that thrives on controlling sexual freedoms. Sex that precludes condoms, according to Tim Dean in Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking, provides new ways for thinking kinship through the transmission of gay and queer culture in the sharing of semen and the HIV virus. Others, including scholar David Halperin, argue that there is nothing to support Dean’s claim that “erotic risk among gay men has become organized and deliberate, not just accidental.” Instead, Halperin argues that safe sex, as we know it, was a gay, grassroots innovation. Overtime, according to Halperin, through sexual experimentation, gay men have created workable, because they are condomless, practices for reducing the transmission of HIV.

Again, for the purposes of this piece I am not interested in whether Natete (1993) or Dean (2009) and Halperin (2007) — two white male queer theorists — are correct. Rather, I want to focus on the thing that all three agree on; that condom usage — as a constant sexual practice — is unenjoyable and untenable. I focus on this coincidence because I wonder what it would mean to extend the frame of radicality or experimentation to the viewing of black women’s sexuality. Sexual risk as a public health debate and media spectacle has certainly affected the lives of all black people. But maybe sexual risk doesn’t register as a useful agential practice for poor black women because structurally their lives are given to so much risk in general. In Just Another Girl this is represented through Chantel’s experiences with street harassment, men touching and grabbing her without consent, the disciplinary mechanisms of a school that (despite her high GPA) demands she act more “like a lady,” a federal agency that makes it illegal to discuss abortion as an option, and — of course — blackness and poverty.

Halperin limits his comments on sexual experimentation to white gay men because their experiments have led to results, the reduction of HIV transmissions which are still relatively high among black gay men. This is a troubling move for me, because it limits the ability to think of black queer folks as their own sex scientists; participants in discoveries that Halperin claims only white queers benefit from. I know that I never personally planned on having sex without a condom, but truth be told I’ve never been any good at planning. The creative and manageable ways I have come to think harm reduction for myself (pre- and post-PrEP) fluctuate. I know many black gay men would agree. As far as Chantel and her friends are concerned, I know I don’t (and cannot) feel what they feel, but I do feel with their ambivalent and sometimes confused desires when it comes to sexual pleasure. I feel with their compulsion to try new things even if I think it may end disastrously. I’ve made mistakes before. I know what it is to have a condom break on or in you. I know naming mistakes and disasters, especially as they apply to black people, is a highly subjective process. I would like to propose that we consider feeling with as a mode of thinking how black people navigate risk. This may give us a way to think what kinship might look like past identity. This might lead to a way of naming a praxis that’s already in practice. The unmentioned and too often unmentionable ways that black cis and trans men and women find possibly similar but not equal ways of operating through sex in an anti-black world that puts death in front of your face every day.

*emphasis added