Western Addition library; photo: Beth LaBerge

At a recent panel discussion at SFMOMA, Michelle Jeffers from the San Francisco Public Library was one of six invited speakers addressing the topic of “the arts and public service.” Jeffers is the library’s chief of community programs and partnerships, and her overview of what the library is doing with the city’s local communities was inspiring and humbling. Included in a very long list that included hundreds of weekly story times for kids, free summer shuttles to nearby national parks, and art exhibitions, Jeffers casually mentioned a rather astonishing activity . . . 3D printing workshops to make new arms for children who are missing limbs.

With programs spanning the mundane to the extraordinary, Jeffers and her staff of thirty are always finding new ways to make the library a source of “public knowledge.” It’s no accident that Public Knowledge also serves as the title of a two-year-long collaborative initiative between the library and SFMOMA. It brings together artists, scholars, librarians, community organizers, and city residents to ask tough questions about the cultural impact of urban change, and to carry out artist projects, research, public programs, and publications.

We sat down with Jeffers and city librarian Luis Herrera to talk about the Public Knowledge collaboration, and what makes for a great twenty-first-century library.

Claude Carpenter, Larry Williams, and Alonzo Walker perform at the Hit Parade Storytelling day at the Bayview Linda Brooks-Burton Branch Library, May 13, 2017; photo: Beth LaBerge

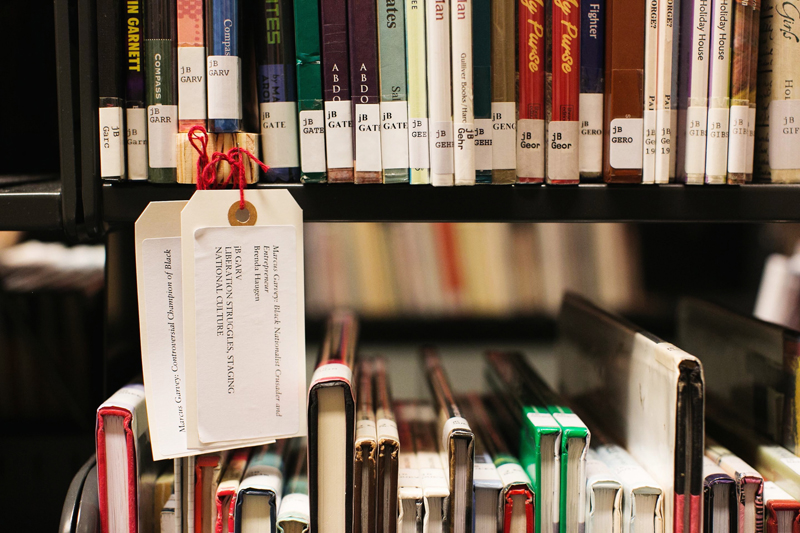

SFMOMA: As I understand it, the precedent for Public Knowledge was the 2014 Chimurenga Library, an installation and research project at the Main Library by the South African artist collective Chimurenga.

Michelle Jeffers: That was so fun and exciting, but it was like Christmas morning, kind of sudden. The Chimurenga people brought in the materials, they were installed for a month, and then it was gone. But after that, SFMOMA knew we were willing to try different things. That led to the more recent discussions with me and Luis about a bigger project that would be less about overlaying something on top of what the library does, and more about engaging with the community.

Luis Herrera: The partnership is such a nice match. Not least because partnership is one of the pillars of our strategic plan. I’ve been involved with the Institute of Museum and Library Services for quite a while now, and one of the things I’ve learned is how much we have to gain from collaborations between the two institution types. In meetings with key members of the SFMOMA team, they said, wow, this is an opportunity for us to take what we do to a much more grassroots, community-based level. I think that’s what’s going to make this such a success — it leverages what we already do well. We’re about civic engagement, building community, and this program speaks to it so beautifully.

SFMOMA: A lot of museums struggle with their mandate to be open, accessible, and educational, because of the stereotype that they’re elitist. (And it’s true, at least in the United States, that you usually have to pay to get in.) Do you think that one benefit of this partnership will be that the library can help the museum become more accessible?

LH: I hope so. The common ground is that we’re both institutions for learning. We’re constantly thinking about the future of libraries. One thing we’re emphasizing is that it should be a user experience. When you go into a library, you should be allowed and enabled to learn at your own pace, in an informal and unstructured way. That’s similar to a museum, right? And as with art, learning can be a creative experience that is very personal.

Western Addition Library; photo: Beth LaBerge

SFMOMA: Tell me something about the first artist project in Public Knowledge, Josh Kun’s Hit Parade.

MJ: It’s about listening to music, but also surfacing stories about people who made music in San Francisco over the last forty or fifty years. A lot of them we were already seeing as patrons, but we didn’t know these stories about them. I went to the Bayview session, and the musicians said, “Of course, we use this branch all the time,” but our library staff would never have known them as well-regarded musicians from the 1970s. It was exciting for us to see these secret superhero powers that our patrons have.

Inna Arzumanova intervies Bobby Webb for the Hit Parade storytelling day at the Western Addition library, April 15, 2015; photo: Beth LaBerge

SFMOMA: Was there ever a time when the “culture” of the library wouldn’t have allowed for a museum partnership like this? In my archival research, I’ve found that in its early years SFMOMA was doing all sorts of rather inventive outreach stuff, like working with the Red Cross on art therapy for World War II veterans. The institution seemed more fearless back then, perhaps because there was a perception that less was at stake. I’m just wondering if libraries have experienced their own larger trends along those lines.

LH: At one point, for a lot of libraries, the culture was, “Come to us; we won’t go to you. We sit at a service desk, and you need to seek us out.” We’re trying to flip that model and be much more community focused, and user-centric. That’s a paradigm shift. One of the biggest growth areas we’ve seen is in program engagement. More than five hundred thousand people are participating in our programs, at the libraries and elsewhere. Certainly people are coming to the library, but we’re also going out and working with nonprofits and community groups precisely to meet people’s needs, and turn them into library patrons. Museums by nature operate under the “you come to us” model, and as you mentioned earlier, there indeed can be a feeling of, “Is it really for me? Do the collections speak to my personal experience?” In undertaking this partnership, SFMOMA is breaking that mold by going out into the neighborhoods, into the community.

SFMOMA: Do you think the On the Go programming during its closure for construction sparked something in that respect?

LH: My impression is that On the Go was a real awakening, and the museum realized it can never go back to the way it was before.

SFMOMA: Do you work with other museums?

MJ: We’ve done some work with, and are always looking for deeper engagement with, the de Young. There’s a summer program where their youth ambassadors come in and lead programs here. It gives them experience with a new audience. I’m so proud of that work. And we collaborated closely with the California Academy of Sciences when we developed our teen center on the second floor of the main branch, called The Mix. They were our partner in thinking through the programming and the physical space.

LH: That thirteen-to-eighteen demographic is really hard to reach, and The Mix has been great. And that partnership meant, for instance, that we didn’t have to reinvent the wheel in terms of figuring out the digital media aspect. I want to underscore that as a game changer for us: working with institutions that have a lot of cachet in terms of their educational programming, and finding ways to leverage their expertise to build capacity for us. Then there’s the National Park Service. It’s not a museum, but—

MJ: This is our second year partnering with them on our Summer Stride reading program, which has gone beyond just counting how many books you read or how many hours you spend reading, to promote going outside, and learning about nature and science through the park visits. They are providing talks with park rangers and shuttles from the libraries to the parks every Saturday over the summer. I thought, when they proposed this, that I would struggle to get thirty people on those shuttles, but it’s been hugely successful. I didn’t think through what a barrier it would be to get your kids to a national park if you don’t own a car.

LH: We all know about summer reading programs, we grew up with them. This is such a different model. And it’s been a record-breaking engagement: 18,600 people last year. The statistic that stands out for me is that 59 percent of the people are first-time participants in a library program.

SFMOMA: How do you promote the park program such that you’re able to reach all those first-timers, if by definition they haven’t been to the library before?

MJ: Recognizing that the park program would be particularly appealing for families, we got the information out to the schools. If in June you were finishing kindergarten through fifth grade anywhere in San Francisco, your teacher gave you a packet toward the end of the school year with a summer reading game board and brochures for our various programs. We also use both agencies to cross-promote. So for instance there’s a summer reading sign-up at all of the parks’ visitor centers, and we display their materials at the libraries.

SFMOMA: That’s fantastic. I was here with a friend the other day, at the exhibition downstairs of women eco-artists, and she made an interesting comment about how it’s difficult to leave school without having acquired skills for appreciating books and literature, but many people never take music appreciation or art appreciation and thus go through life without those skills in their “toolbox.” It made me think that perhaps programs like Josh Kun’s Hit Parade are filling that very gap. Did you perceive that patrons who stumbled onto Kun’s music program amid the library stacks found it surprising or strange?

LH: I think it excites people. I don’t think seeing art or music in the library is jarring at all. People find it refreshing. They say, “Wow, I guess the library does this too!” We get that all the time — that people didn’t know the library did this or that. It was evident as well with the Chimurenga exhibition.

MJ: It was serendipitous to come across Chimurenga because it wasn’t in the spaces we usually dedicate to art. Luis has created a culture here where it’s okay for us to experiment. He really never says no! With that show, SFMOMA came in and proposed putting stuff all over the floor of the Main Library, and I asked, “What do you think, Luis?” and he said, “Sure, that’s great!” He says yes a lot. It’s not about protecting ourselves. Even though we deal with a sometimes challenging patronage. One Mother’s Day we worked with the International Museum of Women. They blew up these twenty-by-thirty-foot portraits of mothers and wheat-pasted them onto the exterior of the library. We wondered if it was going to damage the building, but we lucked out!

LH: That’s a great collaboration example.

MJ: It was beautiful, and again, not what you think you’re going to see when you come to the library. That’s our guiding light, in a sense: it’s not what you think. Sometimes we host controversial exhibitions, and we stand by them because it’s a community process to propose exhibitions for the library.

Installation shot from Chimuranga Library at the Main Branch of the San Francisco Public Library; photo: Andria Lo

SFMOMA: Are a lot of these attitudinal changes you’re describing part of a larger movement?

LH: It’s a relevant and progressive trend that I see among colleagues at other urban libraries — actually all types of libraries. There’s exciting innovation going on, nationally and internationally. You can readily separate the progressive libraries from the old-school. I’m sure the same could be said about museums. I’ve been doing this for forty years, and I can walk into any library and immediately tell if it’s hip or not.

SFMOMA: Michelle, your day-to-day must be hectic, managing all these activities. Are you on the receiving end of a constant barrage of ideas for new programs?

MJ: [laughs] I have a great team of programming librarians for each age group, as well as curators, graphic designers, and a communications team, always suggesting things. They’ve ended up here because it’s what they want to do; this place is not necessarily for anyone with a library science degree.

LH: We do push the envelope. Part of it is having a team with amazing creativity, who say yes to a lot of stuff.

MJ: They also challenge us quite a bit. I must have at least one conversation every day about democracy. Something will come up, and someone will say, “That’s a privacy right,” or “That’s a First Amendment right.” Sometimes it can be uncomfortable or difficult, but in the end I feel really lucky to constantly have discussions about people’s rights to use our space.

SFMOMA: Related to that, I was wondering, in the case of your SFMOMA collaboration, about instrumentalization — meaning, institutions “using” each other, and who has more to gain or lose in terms of reputation, patronage, or whatever kind of cachet. As an analogy, just for instance, I’ve heard of several cases where artists had to be scolded because they were coming to sites with a lot of refugees and trying to involve them in art projects, thinking they were doing a public service, whereas the refugees felt instrumentalized, used, to attract media attention and grant money.

MJ: That comes up a lot in my communications role: artists and people from the media who want to come in and interview people experiencing homelessness, or take pictures of them. We’re always firm in saying no. We have a right to protect their use of this space without being constantly “served” or questioned. They’re our patrons too.

LH: Yes, there’s profiling of certain user types. Our key message has always been that we’re inclusive. All are welcome. We have a very intentional campaign to make sure that people feel welcome. Frankly, I think museums can learn from what libraries are doing in pushing that value of inclusivity and democracy. It’s a big deal for libraries right now.

SFMOMA: I love it that you are counting the first-timers with the National Parks shuttle program. Museums could do more to track first-time users, and make it a goal to grow those numbers.

LH: Speaking of metrics, we’re likewise pushing the envelope by creating an analytics team because we want to measure the impacts of the user experience. Libraries have traditionally been known to capture data and then not do anything with it. We want to translate numbers into outcomes. For instance as part of our early literacy programming we’re engaging with parents: Now that you come regularly to story time with your kids, is your child reading more on his or her own? Yes. Is he or she maintaining their reading level during the summer hiatus? Yes. That’s a powerful thing.

MJ: I want our analytics person to look into whether parents who bring their children to story time lower their own risk in a couple of metrics around “success as parents.” We have hundreds of story times every week, and they’re not just good for the kids; they’re opportunities for the parents to engage with other parents who are in the same boat geographically and demographically. The Department of Health has anecdotally noted to me the benefits of parents taking their small children to story time.

SFMOMA: Do you have particular aspirations for the SFMOMA partnership?

MJ: For me, it’s that cross-promotion we discussed. Hopefully we can make some of the library’s patrons SFMOMA patrons, and vice versa. It reminds me of the idea — and this is something SFMOMA does well — that a museum is more than a place. It’s a concept. We aspire to that for the library, too. So perhaps that would be an example of us following SFMOMA’s lead in a way.

LH: I see both institutions as helping to weave and tell stories. This partnership, if it’s successful, will be about effective storytelling, and promoting the cultural narratives of our neighborhoods and communities.