This fall, SFMOMA presents two exhibitions featuring the work of two American masters: Walker Evans and Robert Rauschenberg: Erasing the Rules. Although the names Walker Evans and Robert Rauschenberg are rarely mentioned in the same sentence, there are indeed interesting commonalities and divergences between the two artists’ works and processes. In this conversation, exhibition curators Clément Chéroux and Sarah Roberts discuss the (at times) surprising relationship between the art of Walker Evans and that of Robert Rauschenberg.

Left: Walker Evans, Self-Portrait, 1927; collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ford Motor Company Collection, gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

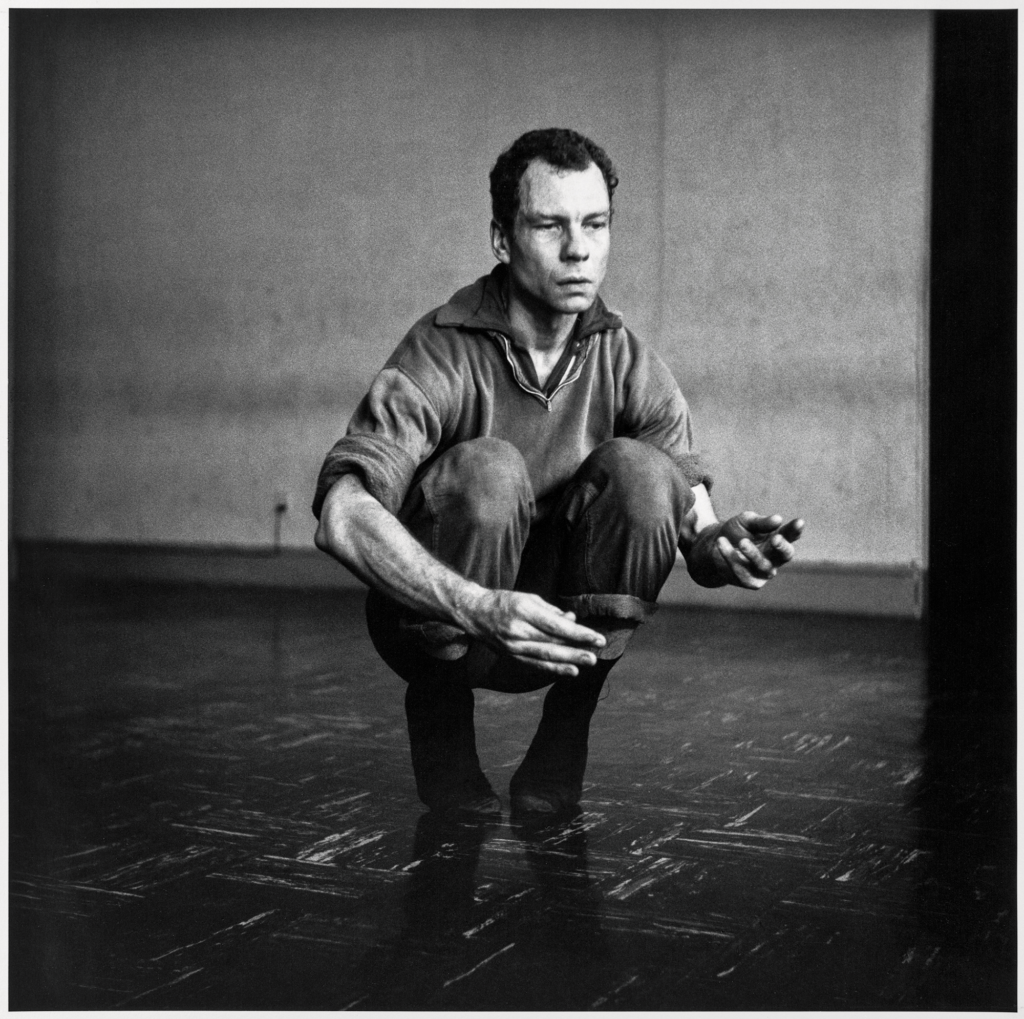

Right: Dennis Hopper, Robert Rauschenberg, 1966 (detail); © Dennis Hopper, courtesy The Hopper Art Trust

SFMOMA: Let’s start with the concept of the American vernacular. How does it feature in the work of Evans and Rauschenberg?

Clément Chéroux: It’s a very useful word for a discussion of Walker Evans, even if Evans himself hardly ever used it. First, it carries connotations of the utilitarian, something to be used for something. Second, it’s always related to a specific place — perhaps a specific house, or the domestic realm in general, or a village or a country. And third, it always describes something popular. Not high culture, but low culture.

For Evans, the model was definitely the photographer Eugène Atget, who was interested in the Parisian vernacular. Evans discovered Atget in 1929 through Berenice Abbott, who had recently returned to the United States from Paris, where she had been working with Man Ray. At that time, Atget was living on the same street as Man Ray. In 1927, when Atget died, Abbott bought his entire archive, something like ten thousand prints and negatives (today they are housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York). Atget’s work was a profoundly important visual influence for Evans.

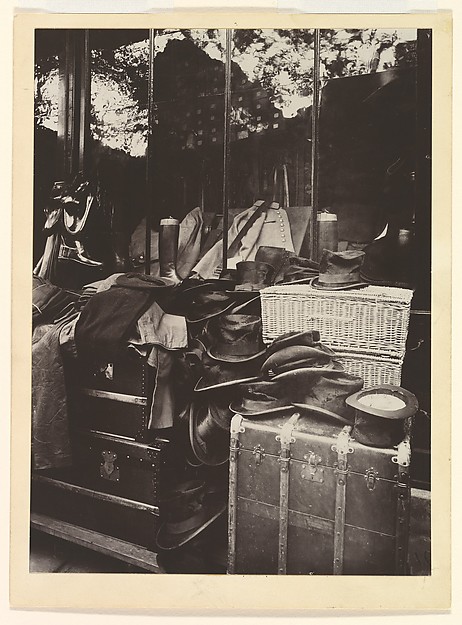

I was very surprised to notice that one of Atget’s photographs, Boutiques, Marché aux Halles (1925), was in both Rauschenberg’s personal collection and Evans’s personal collection. We are showing the print from Walker Evans’s collection in the exhibition, and that particular print was made by Berenice Abbott!

Eugène Atget, Boutique, Marché aux Halles, Paris, 1925; printed ca. 1929; collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel

SFMOMA: Wow.

CC: Both Rauschenberg and Evans were fascinated by this Atget photograph, which manifests the Parisian vernacular of the time. It shows the window of a boutique selling clothes and art. Evans photographed a lot of shop windows over his career.

Sarah Roberts: Looking closely at what’s in the window, I can see shoes, pants, hats, steamer trunks, and furniture. But my eye immediately goes to the reflection in the window, and in that sense, this photograph does what a lot of Rauschenberg’s paintings do — namely, there is something on the surface, but then it’s also bringing you in through the reflection. There’s a reality that is exterior to the piece that then becomes part of what we’re looking at.

CC: That’s so interesting.

SR: Also the jumble of everyday stuff is important. It is the defining characteristic of Rauschenberg’s Combines: taking ordinary things like items of clothing, comic books, scraps of wood, pieces of tin, food containers, and incorporating them into the surface of a painting. An allover glance at a pile of stuff is very Rauschenberg.

CC: So this Atget picture is like a Rauschenberg Combine photograph.

SFMOMA: Are there other ways to talk about the vernacular as it pertains to Rauschenberg’s work?

SR: Painting for him was not just oil on canvas. He regarded all sorts of things as equally valuable, equally interesting, equally worthwhile to put into the surface of a painting. That leveling of materials goes along with his interest in everyday items. He really liked humble scraps. He found them visually interesting, texturally interesting, and loaded with potential associations. And when he juxtaposed these scraps with strokes of paint, the results broke new ground for him and for painting.

CC: Evans also took an avid interest in things like shop windows and billboards. For him it was in part because they spoke about the everyday, but he readily extrapolated from there to regard them as also speaking about America. As with Atget for Paris, he thought street scenes defined a kind of spirit that is typical to a country. He thought that there is as much American spirit in roadside stands, signs, and main streets as there is in literature or “important” architecture.

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham/Roadside Store Between Tuscaloosa and Greensboro, Alabama, 1936; collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SR: For Rauschenberg it was a different impulse, I’d say. In trying to make a connection to the real world he was responding to the Abstract Expressionists, a generation of painters who dominated the New York scene when he was coming of age as an artist. He was reacting against their inward focus, their idea of painting as an expression of individualism or a personal emotional landscape. That was too insular for him. He had a real appetite for life and travel and the everyday world, and literally embedding everyday items into his paintings was a way of reconnecting painting with the real world.

SFMOMA: How would you say these two artists engaged with appropriation and reproducibility in their respective practices?

SR: I don’t think Rauschenberg thought of what he was doing as appropriation.

SFMOMA: But what about the lawsuit, for instance? Rauschenberg’s work titled Pull (Hoarfrost) (1974) incorporated the commercial photographer Morton Beebe’s photograph, The Diver, which had been previously used in an advertisement. That got Rauschenberg into some trouble, right?

SR: Yes, he did get sued for using that image without express permission. At that point, Rauschenberg wasn’t taking very many of his own photographs, and was relying on collecting them elsewhere for his works. That incident was one of the factors that made him start taking his own photos again.

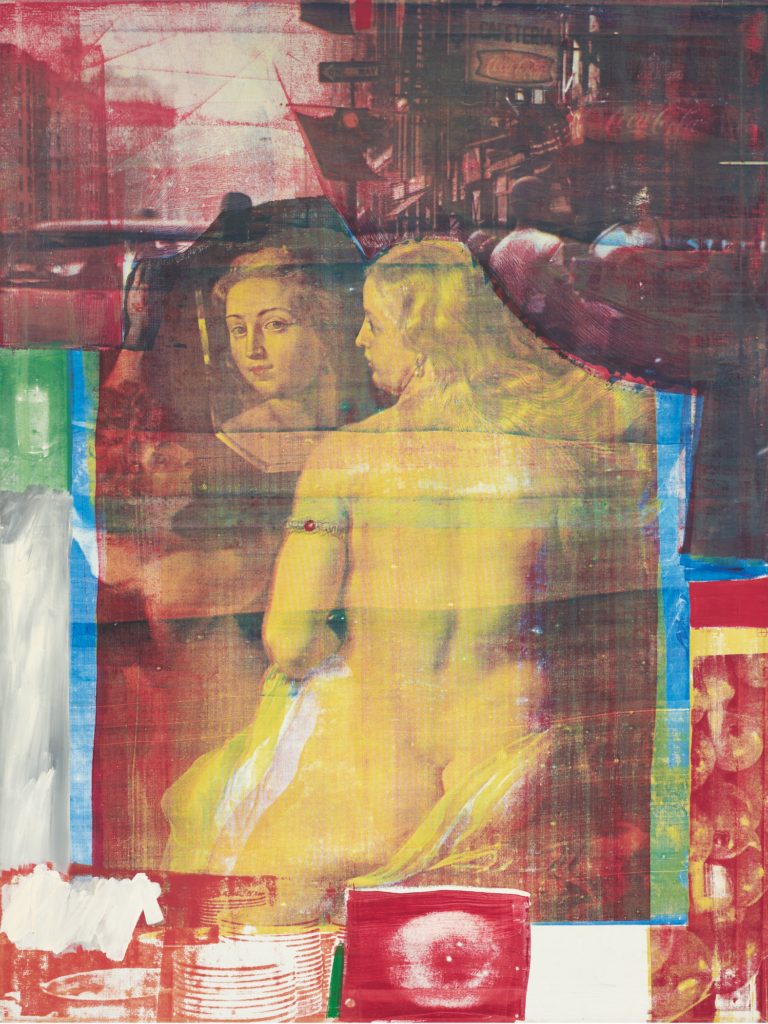

If we’re going to talk about appropriation in the context of Rauschenberg, when he does things like bring in a reproduction of a Peter Paul Rubens painting, it’s intended as an act of leveling, both in terms of chronology — making it contemporary, perhaps by putting it next to an urban street scene — and also leveling in terms of cultural prestige. He’s saying, hey, this is an image like any other, and it’s available to me to put into my paintings. It’s not on the high pedestal of art history anymore. He might celebrate its beauty, or he might wash it out, almost dissolve it. The act of taking images from other sources or artworks is about democratization rather than homage or a stamp of approval of some kind.

Robert Rauschenberg, Persimmon, 1964; private collection; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

CC: I have the feeling that this word “appropriation” is not totally appropriate to Evans, either. I prefer “collecting.” He was fundamentally a collector.

SR: That is a very appropriate word for Rauschenberg, too: “collecting.”

CC: For Evans there wasn’t much of a gap between collecting and photographing. It was a thin frontier. Some of his students have passed down to us stories about driving around with him in the countryside. Sometimes he’d stop because he saw a sign that interested him. He’d first photograph the sign in its context, and then steal it because he wanted to keep it. One of the photographs in the exhibition shows the interior of his house at the end of his life, and you can see how he was displaying signs on the walls as if they were paintings. Photographing and collecting were his mode of appropriating, if you want to use that word. It was a way to say, this is a valuable object, and I should keep it. Or at least keep a trace of it, if it’s too big to take away.

SR: We can say the same about Rauschenberg. He collected photographic images torn out of magazines, posters, books, and newspapers, and he took his own photographs, and they all went into the same stockpile of imagery that he later pulled from. Absolutely, they were intertwined as activities.

CC: With so many artists, sometimes you just don’t know if they are collecting for the purposes of making art, or if they are making art because they have amassed so much material that they need to use it for something.

SFMOMA: I love that idea of the “thin frontier” between collecting and art making. And it leads nicely into my next question, which is about how each of these artists used trash and junk as art materials.

SR: Rauschenberg wouldn’t have thought of any of his materials as trash. The world was his material playground. People brought him things. He gathered metal and wood from junkyards, and he also bought brand-new supplies. All materials were fair game; some of them just happened to be castaway scraps. A piece of gorgeous silk or a page of a newspaper or a car fender — he thought of them all the same way. They all had the same potential for his work.

Robert Rauschenberg, Mirage (Jammer), 1975; Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

In the 1970s, his approach took on an environmentalist aspect. He wanted to find ways of working that recycled both materials and processes, and also, in some cases, commented on the waste that he was seeing. There’s one series in the show called Gluts that’s made up of street signs and salvaged pieces of metal that he picked up around his home in Florida and on a trip to Texas, which is where he was from, and which was then in the middle of a bust in its boom-and-bust cycle of oil production. He was struck by the amount of industrial waste as well as personal junk that had been left behind. He made these sculptural works using salvaged metal, saying that he wanted to show people their ruins.

CC: Evans, for his part, was fascinated with the literary figure of the ragpicker. The French poet Charles Baudelaire made the ragpicker one of his main figures, and the famous theorist and critic Walter Benjamin wrote a lot on Baudelaire and the ragpickers. I have the feeling that Evans imagined himself acting exactly as a ragpicker: someone collecting, as a kind of treasure, what society and the city were rejecting. As you said about Rauschenberg, Evans understood that this was the other side of progress, the dark side of modernity. He understood it already in the 1930s, well before the environmental movement. Usually when you talk about modernity, especially in the United States, you mean Art Deco skyscrapers, or beautiful streamlined cars driving at top speed. Evans chose to depict modernity as an auto graveyard. He was not naive. He understood perfectly that if you increase the speed, you increase the number of accidents. If you increase consumerism, you increase the waste and the junk.

Walker Evans, Garage in Southern City Outskirts, Atlanta, Georgia, 1936, printed 1972; collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Administrative Purchase Fund; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SFMOMA: There’s an interesting contradiction, perhaps, or a conundrum, that both of them were grappling with. They were avidly collecting images and things, and it represented a huge part of their respective practices and fueled their creative output, but at the same time they were criticizing consumerism, and industrial and individual waste.

SR: Rauschenberg reveled in visual excess. He loved walking out into the street and seeing flashing signs, speeding cars, people wearing all manner of clothes, trash, a profusion of goods and images. Life and the world were fascinating to him and fueled him. But later in his life that he recognized the flip side of that. He walked the line of still appreciating, still enjoying, still drawing from, but also trying to make a point about the bigger picture of consumerism.

CC: I would say the same for Evans. And I wouldn’t call it a paradox or a contradiction, but a dialectical tension that he consciously recognized.

SR: Evans had a real affection for that tension, as did Rauschenberg.

CC: It’s part of what makes Evans’s work so great. The tension between high and low, between Europe and the United States, between progress and regress.

Robert Rauschenberg, Rosalie/Red Cheek/Temporary Letter/Stock (Cardboard), 1971; collection SFMOMA; Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Major Accessions; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

SFMOMA: We know that Evans had a painting practice, and that Rauschenberg had a photography practice. Are there some interesting parallels to unpack there?

CC: We are indeed showing a few paintings in the Evans exhibition. His paintings have very, very rarely been shown. He made only maybe forty or fifty of them in all, mostly in the 1940s and the 1950s. At that time he was married to a painter, Jane Ninas, so he had easy access to all the materials for painting. The reason I am showing these paintings is not because I want to prove that Evans was a great painter. He wasn’t bad, but he wasn’t great. Rather, the paintings are interesting because when you look at them, you see exactly the same subjects as in his photographs: little wooden roadside stands, American main streets. The paintings reveal his obsessions with certain subjects.

Walker Evans, Untitled [Street scene], 1950s; collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

SR: Rauschenberg originally thought he would be a photographer. He studied photography and took photos from very early on in his studies as an artist. One of his early, overly ambitious ideas was that he would photograph the entire United States inch by inch, which is obviously not humanly possible, but it gets at this idea of noticing the little details, the insignificant things, that fueled him. It was a way of collecting sites and creating raw material for his own later work.

He did take photographs of friends occasionally. We have some of those in the exhibition. But really his use of the camera was about gathering raw material that could then be deployed using silkscreening, photo transfer, or any number of other processes for getting images into the work. He took photographs pretty consistently through the 1950s, trailed off in the 1960s and 1970s, and then picked up the camera again with energy around 1980, at which point he also began to think about photographs as finished works in and of themselves.

Robert Rauschenberg, Merce, 1953, printed 1981; collection SFMOMA, purchase; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

SFMOMA: Such as his In + Out City Limits series from the 1980s.

SR: Definitely. That series looks at aspects of cities that most people might not notice: looking up, looking down, looking around corners, looking at the textures of buildings. Some of them ended up as photographs, and some of them became images or even just textures that he then washed into another work in one medium or another.

In the exhibition, there’s a group of photographs of family members, friends, lovers, and collaborators that he shot very early in his life. Then toward the end of his life, he made a series of lithographs called Ruminations using the same photos, looking back over these people who had been important to him. The fact that he chose to go back to those photos forty years later in order create a whole new body of work in a completely different medium is pretty fascinating.

Visit SFMOMA through February 4, 2018, to see Walker Evans, and through March 25, 2018, to see Robert Rauschenberg: Erasing the Rules, and investigate for yourself the commonalities between these two important artists.