Pacita Abad made striking, radical works across multiple mediums. Deeply influenced by the techniques of artists and makers she encountered on extensive world travels during the mid-1970s through the early 2000s, she incorporated many of these approaches into her trapunto paintings: canvases painted, then quilted, embroidered, and decorated with beads, buttons, mirrors, and cowrie shells to create an arresting medley of concept, color, and form. The rich density of her works matched her prolific output; Abad made thousands of objects in 32 years. Pacita Abad, organized by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, is the first major retrospective of the artist’s works. The SFMOMA exhibition opening this October features over 40 major artworks.

Pacita Abad was born in 1946 into a family of politicians in Batanes, an island province in the northern Philippines. Her family’s commitment to public service (both her parents served in Congress), as well as the country’s deep-rooted histories of colonization, and its more recent history of the 20-year Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship, were formative and lasting influences in her creative practice. In fact, Abad left the Philippines in 1970 to escape political persecution after leading a student demonstration against the Marcos regime. She intended to move to Madrid to finish her law degree, but a visit to an aunt in San Francisco became a long-term stay that would change the trajectory of her life.

“I have always believed that an artist has a special obligation to remind society of its social responsibility.”

1970s San Francisco was a hub of counterculture and social movements and, for Abad, a point of creative origin. Here, she met Asian and Latin American immigrants who had left their home countries for economic or sociopolitical reasons. Their stories inspired her to think about pursuing immigration law so she could advocate for their causes. At the same time, Abad immersed herself in the local art scene and fell in love with art as a master’s student in history at Lone Mountain College (now part of the University of San Francisco) after working as the school’s Coordinator of Cultural Affairs. Though Abad received a scholarship to attend law school at UC Berkeley, she chose to delay her acceptance for travel. She and her husband Jack Garrity decided to spend one year hitchhiking overland across twelve Asian countries, from Turkey to the Philippines. It was during this trip that Abad decided to forgo a law career and become an artist. Art soon became the conduit and catalyst through which she advocated for marginalized peoples. As Abad stated, “I have always believed that an artist has a special obligation to remind society of its social responsibility.”

Painting gave Abad a way to tell stories, and the easy portability of canvases suited her peripatetic life with Jack Garrity, whose job as a development economist for the World Bank and other international organizations meant frequent relocations. Over three decades with Garrity, Abad spent time in 60 countries, including Sudan, Yemen, Turkey, Afghanistan, India, Mali, Mexico, Guatemala, Dominican Republic, and Peru, with longer stays in the United States, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore. “This had an enormous impact on her practice as far as forms, materials, motivations, and visual traditions she’d learned about,” says Nancy Lim, associate curator of painting and sculpture at SFMOMA, “whether sewing and stitching techniques from Rabari women in Rajasthan, mirror embroidering in India, or embroidery in Burma.”

While Abad lived a life that afforded her the opportunity to see the world and pursue her art, this privilege was tempered by her experience as an immigrant and a woman of color whose use of textiles was a medium often historically marginalized as craft. These factors limited her access to the mainstream art world and relegated her to what she described as “life in the margins.”

“Abad’s ease in moving through distant geographies and connecting with different peoples afforded her a uniquely transnational perspective,” says Victoria Sung, former curator of visual arts at the Walker Art Center and organizer of this retrospective. “She found community and built relationships with artists, exchanging ways of making and incorporating new materials and methods into her art. In the eighties and nineties, few artists were truly global in the sense that she was.” Against this background, the exhibition expands on five themes in Pacita Abad’s work — social realism, masks and spirits, abstraction, immigrant experience, and underwater wilderness — to illuminate her life and art. Except for her social realist works, which were limited to the late 1970s and early 1980s, Abad created across these themes throughout her career.

Social Realist Works

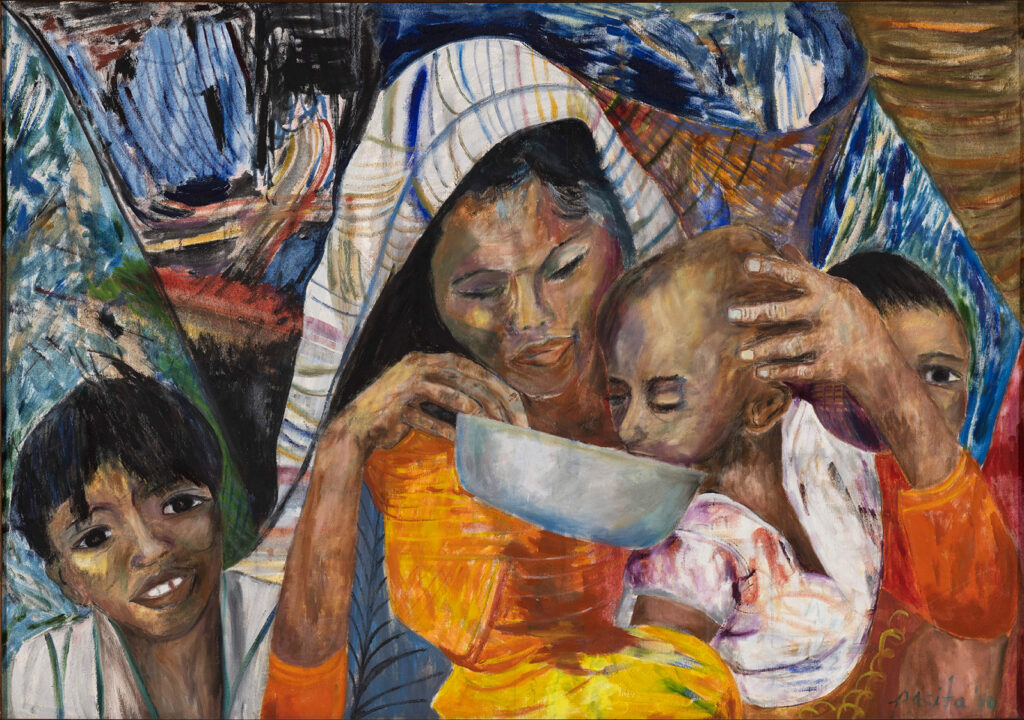

These paintings and drawings, Abad’s first significant body of work, emerged from on-the-ground visits in the late 1970s to refugee camps along the Cambodian-Thailand border. Abad’s friendships with journalists and humanitarian aid organizations in the camps provided access to the refugees sheltered there. Abad visited the camps a number of times, and “the impetus for the series was to shine a light on the humanitarian crisis that was unfolding at the refugee camps,” says Sung. Abad realized the best way she could spread awareness of global issues was through painting: “After the media coverage ends, my paintings keep staring at you,” she said.

Water of Life (1979), a key work, depicts a mother, her children, and the life-giving force of water in the harsh environment of the camps. “Abad was drawn to depicting women and children in her early paintings, because she wanted to make a point that the majority of the world’s refugees are women and children,” Sung says.

Inspired by a sense of responsibility and, in part, by the social realist traditions of artists such as Alice Neel, Ben Shahn, Zainul Abedin, Käthe Kollwitz, and Diego Rivera, these intimate portraits are important markers as the beginning of her practice.

Masks and Spirits

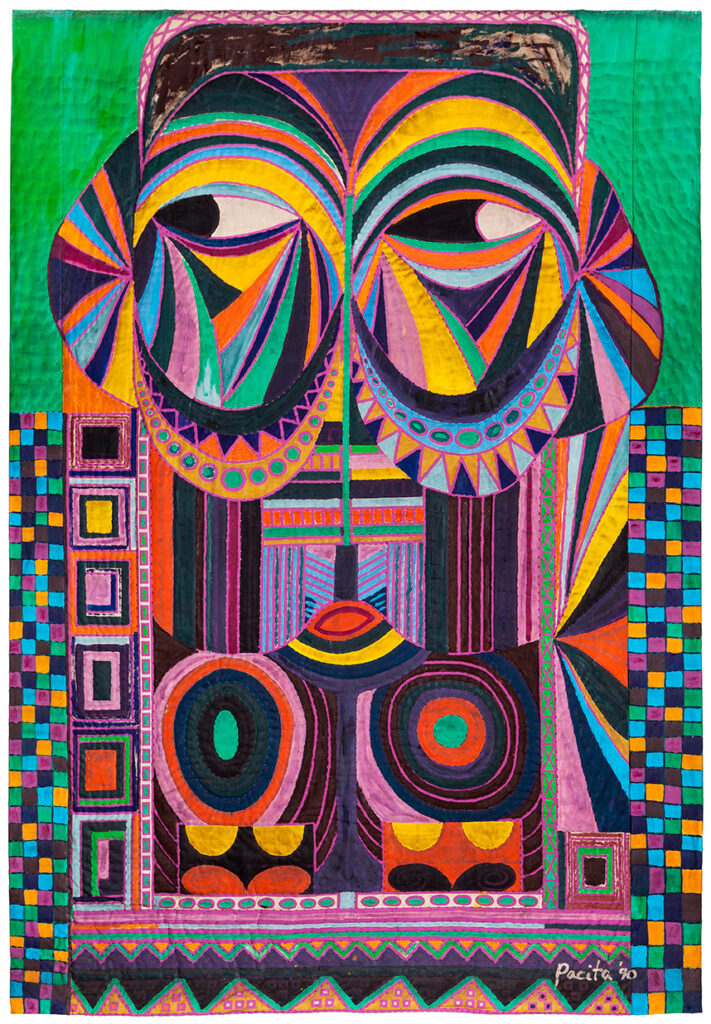

Abad metabolized the techniques she encountered in an approach that was her own. Says Sung, “As she traveled, she was curious about different cultures, ideas, and influences, and really saw no hierarchy in her making. She created a foundation that was open to all forms of artistic creativity.”

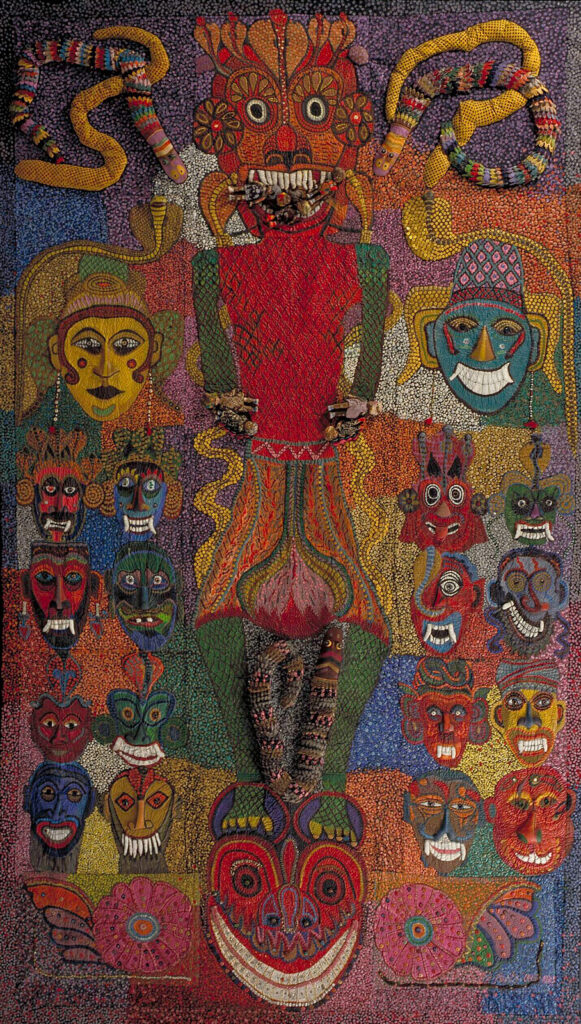

Travel and painting in South Sudan, Papua New Guinea, and Sri Lanka in the early 1980s introduced Abad to the mask traditions of these countries. Her hybrid art form that combined acrylic painting with stuffed quilting — which she called trapunto painting — led to Marcos and His Cronies, one of her largest, most ambitious works. The Sri Lankan Maha Kola mask, which features a central demon surrounded by 18 other demons, inspired this piece, which she started in 1985 and finished in 1995.

“Abad realized the Maha Kola mask was a perfect representation of Marcos and his cabinet of generals, ministers, business tycoons, and other cronies,” says Sung. In the work, Abad identifies by name the figures surrounding the central figure of Marcos; at the bottom a heavily bejeweled mask represents his wife, Imelda Marcos. “Made at a time when there was growing political dissent against the Marcos dictatorship, which eventually led to his departure in 1986 following the EDSA People Power Revolution, this artwork was a bold political statement.”

Abstraction

Beginning in the 1980s, Abad delved into abstraction, reaching her peak in this approach in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Many of these colorfully exuberant pieces are decidedly political in nature, bearing titles like Life in the Margins (2002), White Heightens an Awareness of the Senses (1998), and The Sky is Falling, The Sky is Falling (1998), which was created in Indonesia during the country’s economic collapse.

“Emma Amos, one of Abad’s contemporaries, talked about how in her own painting choosing to use color was a political statement. Amos said, ‘It would be a luxury to be white and never have to think about [color].’ Abad very much used color in the same way,” Sung explains. These are visually vibrant, ebullient works, yet they are influenced by somber events between 1998 to 2002, including the September 11th attacks, the start of war in Afghanistan, and her cancer diagnosis.

“She made these works at the very end of her career while undergoing chemotherapy, and I think you can see in the almost frenzied way in which she built up her surfaces the urgency she felt to get everything out,” Sung explains, adding, “She titled one of her works I Have One Million Things to Say (2002) and that is precisely how I view this series: she wanted to make sure her voice was being heard.”

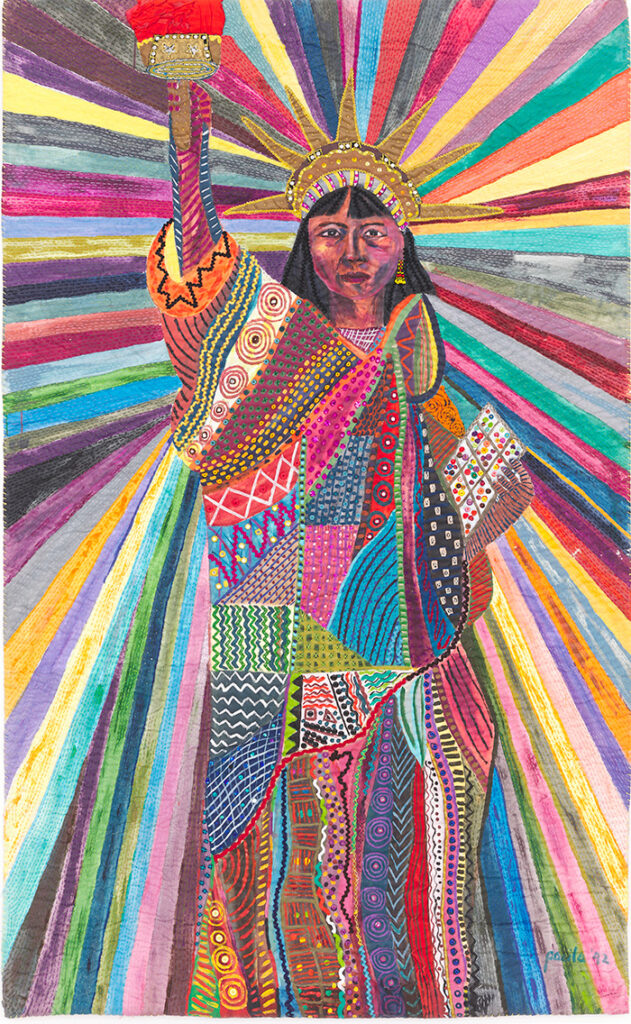

Immigrant Experience

Abad was interested in capturing the contemporary lived experience of immigrants, most especially people of color. This was activated during her United States citizenship process, as she noticed how immigration stories focused on Europeans who came through Ellis Island, not those who came from Asia, Latin America, or Africa through other entry points.

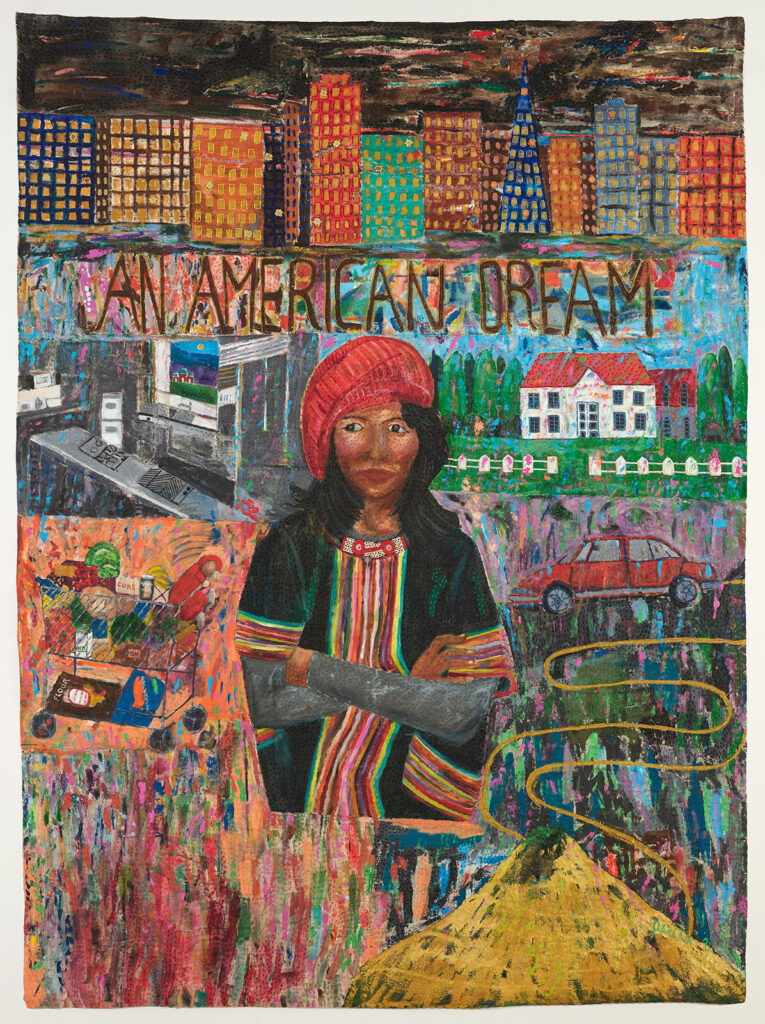

Her Immigrant Experience series from the 1990s was an effort to share the stories of those pushed to the margins, as well as challenge the Eurocentric perspective of the art world. “Art is for other people, it’s not just for yourself,” Abad said in the interview Wild at Art. “Especially for people like us . . . if you want to be included, you don’t have any choice, you’ve got to go out there and tell them.”

“If My Friends Could See Me Now (1991) could be a portrait of the artist, though it’s not strictly a self-portrait,” Sung says of the work in SFMOMA’s collection. “In the foreground is a Brown woman wearing clothes that Abad picked up on her travels, and the work features a car and a grocery cart full of items, a house, and a white picket fence — manifestations of material wealth that many immigrants aspire to when they come to the United States. Then there’s a corresponding work in the series called I Thought the Streets Were Paved with Gold (1991).

Whereas the first work depicts the aspirations, dreams, and ideals of shared prosperity in the United States, the second work depicts the day-to-day realities, for instance showing a Filipinx nurse or a Korean shopkeeper, and all the unseen labor of people of color who literally and metaphorically pave the streets of this country.”

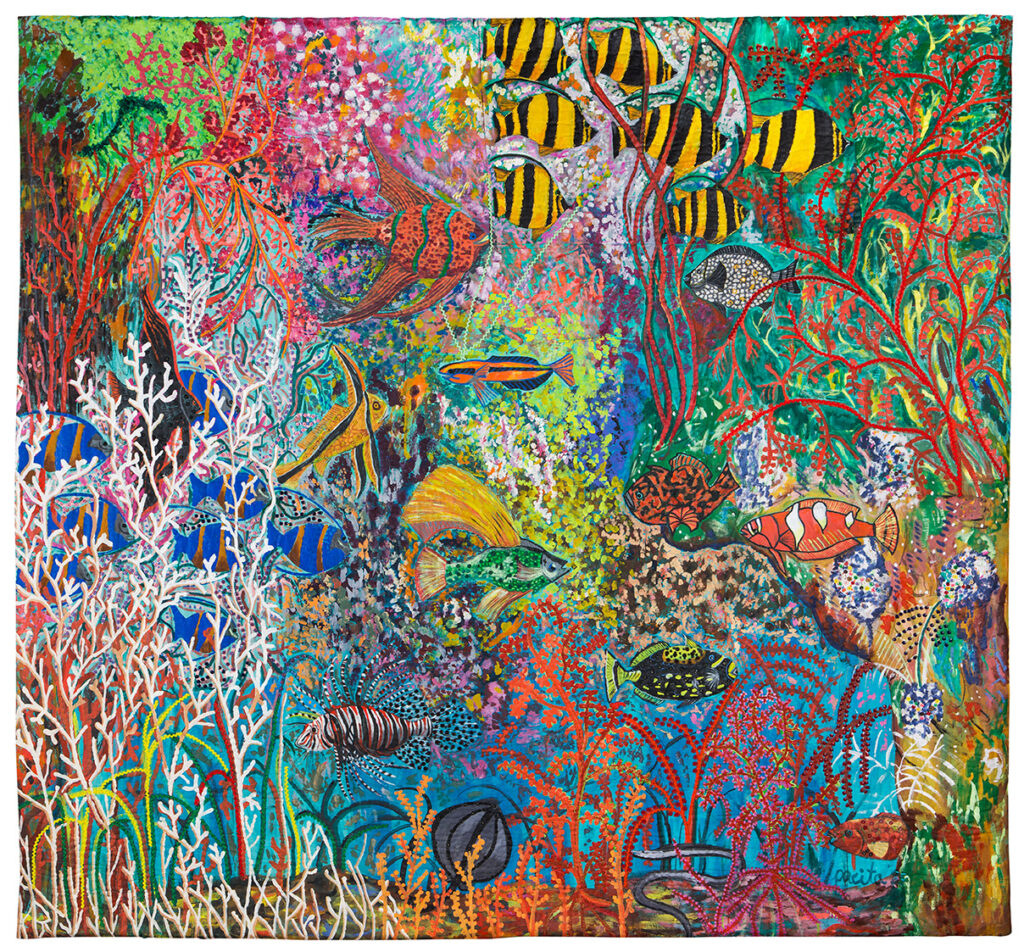

Underwater Wilderness

Abad’s glorious trapuntos of tropical sea life and underwater scenes form the exhibition’s exhilarating finale. Though she grew up surrounded by water, Abad didn’t learn to swim until adulthood. Once she learned, she went all in with her typical passion, becoming a certified scuba diver in 1982 and dedicating this series of works to the peace she felt in the ocean and her concern for its environmental protection.

The massive trapuntos, My Fear of Night Diving: Assaulting the Deep Sea (1985), Anilao at Its Best (1986) , and Dumaguete’s Underwater Garden (1987), depict vibrant aquatic paradise dense with fish, corals, and rocks that use plastic buttons, rhinestones, and iridescent fringe to further animate the color-soaked scenes. “Do they have a political current?” Sung asks. “I would say yes, but they are political in a more oblique way. Works like Puerto Galera, for example, reference the centuries-long galleon trade between Manila and Acapulco during Spain’s colonization of the Philippines. Abad also talked about how she felt like an intruder or an interloper when she would go scuba diving. She had a real sensitivity to the precarity of underwater ecosystems and how human beings interact with the environment.”

When asked in 1991 what she had contributed to American art, Abad exclaimed, “Color! I have given it color!” Experience this long-overdue retrospective and immerse yourself in the artist’s radical practice and the mesmerizing artworks she created.

Pacita Abad is on view from October 21, 2023, through January 28, 2024, on Floor 4.

Pacita Abad is organized by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Presenting support for Pacita Abad at SFMOMA is provided by the Neal Benezra Exhibition Fund.

Major support is provided by the Mary Jane Elmore West Coast Exhibition Fund, The Elaine McKeon Endowed Exhibition Fund, the Stuart G. Moldaw Public Program and Exhibition Fund, Rummi and Arun Sarin Painting and Sculpture Fund.

Generous support is provided by Pat Wilson.

The Walker Art Center organized the exhibition with major support provided by Martha and Bruce Atwater; the Ford Foundation; the Henry Luce Foundation; the Martin and Brown Foundation; Rosemary and Kevin McNeely, Manitou Fund; and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.