This selection of books was chosen by Frank Bowling and one of his sons, Ben Bowling, for the exhibition Frank Bowling: The New York Years 1966–1975, on view May 20 through September 10, 2023, on Floor 7. Discover these books, notes from Frank Bowling’s teaching, and interviews with the artist in the exhibition galleries.

Art and Culture: Critical Essays by Clement Greenberg, 1961

Bowling became good friends with American art critic and advocate for abstract painting, Clement Greenberg, and corresponded with him for many years. Bowling said in a 2007 interview with Mel Gooding: “It was only when I actually stopped writing, in about 1971 [and] just got into my own work. And, as luck would have it, just at that point I met Clem Greenberg, who encouraged me to think the way I was, but getting it in the work. There was no point in me writing any more, because it was time for me to just show it, to do it.”

The Elements of Dynamic Symmetry by Jay Hambidge, 1926, re-published by Dover Publications, New York, 1953

Bowling’s interest in geometry originated in his study of technical drawing as a teenager and his work as an apprentice in his uncle’s cabinetmaker’s workshop. This extended to an interest in formalism through the close study of geometry especially Hambidge’s symmetry, the mathematics of Fibonacci, and the use of geometry by artists such as Piet Mondrian, Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal), Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman. The importance of geometry to his work stems in part from his interest in and Royal College of Art dissertation on Mondrian. In developing these ideas, Bowling set up a discussion group in 1963–64 with his friends, engineer Paul Harrison, architect Jeremy Thomas, and sculptor Jerry Pethick to discuss issues regarding geometry and architectonics.

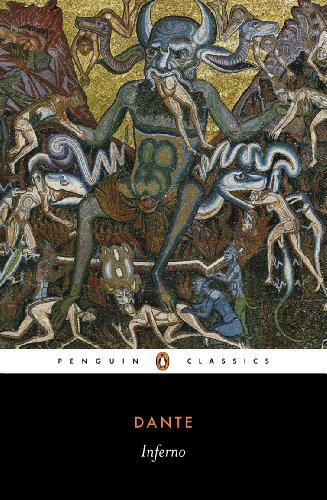

Inferno by Dante Alighieri, 1472

Inferno is the first part of Dante’s epic poem The Divine Comedy. It explores the punishment for sins including self-deception, treachery, and greed. Inferno had a profound effect on Bowling, and it is referred to either directly or obliquely in many of his paintings. Dante’s Inferno included references to the god Saturn (or Cronus in Greek mythology) devouring his children out of fear that they would overthrow him, which is also a popular subject in visual art including in the work of artist Francisco Goya, one of Bowling’s early influences, as well as in the work of Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, and Peter Paul Rubens. Bowling’s figurative works from the 1960s also address this scene.

Mondrian by Frank Elgar, Thames and Hudson, 1968

Bowling wrote his dissertation on Mondrian at the Royal College of Art. He wrote for Arts Magazine and was a fierce critic of books and exhibitions. On Frank Elgar’s book he wrote: “This is a highly eccentric if overwritten and repetitive book. Essentially what Mr. Elgar is saying is that he finds Mondrian not just an interesting artist-painter but also an interesting man, and he would like us to know this. This is perhaps for the nonart public. Indeed in a book of this sort the real value is only in the profusion of illustrations; It’s a kind of bedside book for gazing sleepily at the pictures.” —Arts Magazine, April 1969

Handbook of Ornament: A Grammar of Art, Industrial and Architectural Designing in All Its Branches for Practical as Well as Theoretical Use by Franz Sales Meyer, 1888

A well-thumbed copy of this is in Bowling’s London studio. Sales Meyer’s 1888 book, A Handbook of Ornament, relates to Bowling’s interest in geometry and sculptural form that can be found in all of his works. The book has 3,000 illustrations of the elements and the application of decoration to objects and provided indicative compositions for a number of his works.

Private View: The Lively World of British Art by Bryan Robertson, John Russell, and Lord Snowdon, 1965

This book documents the early 1960s London art scene and includes studio visits with Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Graham Sutherland, Francis Bacon, Victor Pasmore, David Hockney, Lucian Freud, and Bridget Riley, among many other legendary painters. Private View includes photographs of Bowling with his first son, Richard Sheridan (Dan) Bowling, and also an image of Beggar No. 1 & 2 (1963).

The Guyana Quartet by Wilson Harris, Faber and Faber, 1985

Bowling met Wilson Harris, an author who Angela Carter refers to as “The Guyanese William Blake,” in the 1980s. Set in Guyana, this epic masterpiece is a radical landmark in modern literature, by an author that describes: “An ancient landscape of rainforests and swamplands, haunted by the legacy of slavery and colonial conquest. It is the site of dangerous journeys through the Amazonian interior, where riverboat crews embark on spiritual quests and government surveys are sabotaged by indigenous uprisings. It is a universe of complex moralities, where the conspiracies of a sinister moneylender and the faked death of a murderer question innocence and inheritance. It is a place where life and death, myth and history, philosophy and metaphysics blur. And it is the birthplace of an epic masterpiece.” The book has inspired titles in Bowling’s work such as Towards the Palace of the Peacock (2020).

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, 1970

Bowling met the writer Toni Morrison in New York in the late 1960s, and they became close friends. Bowling recalls having intense debates with Morrison about art, politics, and love relationships across the “color line.”

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, 1927

Before turning to art, Bowling focused his studies on literature and poetry. Virginia Woolf’s 1927 novel, To the Lighthouse, had a profound influence and gave a title to at least three of his paintings.

Jasper Johns by Max Kozloff, 1967

In his essay “Another Map Problem” in Arts Magazine (December 1970–January 1971), Bowling writes the following: “Max Kozloff in his book on Jasper Johns spends much greater energy in discussing where the paintings don’t fit into a concept of Apollonian aspirations through structure, rather than on the structures themselves. Of the map done in 1961 and now in the Museum of Modern Art, Kozloff says Johns ‘…betrays such an indifference to geography that the United States are swamped in shrill yellows and reds and light blues, without any compensating adjustment of stroke to image. It is an unravelled, acrimonious picture.’ […] What one sees after, and in, connection with False Start (1959) is the demand of mobile paint structures. Linear space or plane structures, which lend to a one-to-one color articulation, become considerably undermined when color is busier, more natural, more fluid. If the control of False Start is direct and intuitive, the maps with their ‘stepped’ but natural up-and-down, left-and-right, right-and-left, stuttered diagonal drifts, looping bellying lines, demand [within the rectangle] a certain kind of order that Johns seems unwilling to pursue.”

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, 1880

This is a classic that Bowling read at the Royal College of Art that deepened his understanding of fraternal relationships.

Turner and the Masters, ed. David Solkin, Tate Publishing, 2009

This is the catalogue for an exhibition at Tate Britain that placed masterpieces by Canaletto, Rubens, Rembrandt, and Titian next to some of J.M.W. Turner’s most dramatic paintings. The show shed light on Turner’s “obsession to prove he was just as good, if not better, than the old masters who he so admired.” Bowling said in a 2021 interview with The Art Newspaper: “when I arrived in London in 1953 it felt like coming home. London was Turner’s town, and where I got acquainted [with] works by [John] Constable and [Thomas] Gainsborough and the old masters that I discovered in The National and Tate galleries. So, coming back to London in the mid-70s also brought me back to that, and to the English landscape tradition. Having studios in both cities gave me the best of both worlds. In London, I was able to connect with my painterly roots in the English landscape tradition, taking on Constable and Turner so to speak, and in New York I was engaging with post painterly abstraction, and the greats of American abstract painting — Rothko, Newman, and them.”

The Paintings of Titian, Volumes 1–3 by Harold E Wethey, 1969

A constant on Bowling’s bookshelf. As Bowling once described in conversation with art critic Mel Gooding: “I gradually moved to looking harder and harder at Titian, and this is when I, I found that, I could open up, you know, There are ways of proceeding to make a picture that I found, that I thought I spotted in Titian, that I was going for.”

The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon, 1961

Bowling’s interest in existentialist philosophy, in the work of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus, led him to the radical philosophy of the French Martinican psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon.

Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora by Stuart Hall, 2019

Bowling met Stuart Hall, the Jamaican-British academic, writer, and cultural studies pioneer, through his work with Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts) — an evolving, radical visual arts organization dedicated to developing an artistic program that reflects on the social and political impact of globalization.

London Review of Books and The New York Review of Books

Bowling has been an avid reader of and subscriber to the London Review of Books and The New York Review of Books over many decades.

Header image: Frank Bowling, False Start, 1970; Minneapolis Institute of Art, the John R. Van Derlip Fund, © Frank Bowling, all rights reserved Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London, 2022