Courtesy Rod Humble

Rod Humble, PC game maker and longtime industry professional, has worked for most large video game companies in a senior-level capacity, including Linden Lab (creator of Second Life), ToyTalk, and the EA Play label of the game company Electronic Arts (where he worked on The Sims 2 and The Sims 3). He is currently general manager at the San Francisco studio Jam City, formerly SGM. In parallel, he has developed several of his own games, experimenting with the medium as an art form and a means of self-expression. In this interview, Erica Gangsei, SFMOMA’s head of interpretive media and creator of the PlaySFMOMA initiative, talks with Humble about his personal and professional projects, and his aspirations for games and gaming.

Erica Gangsei: How did you first start out in games?

Rod Humble: I wrote my first computer game in 1977, when I was eleven. A little biplane simulator.

EG: What appealed to you about games then?

RH: I didn’t really have a choice. Some things, you just come out inclined that way, right? I met all of my friends through games like Dungeons and Dragons. My earliest memories are of playing with toy soldiers in a sand pit. In England, where I grew up, miniature war gaming was big and there was a culture of making your own rules.

EG: Can you talk about the late 1970s and early 1980s and that DIY culture of being a game player, and how it evolved in subsequent decades?

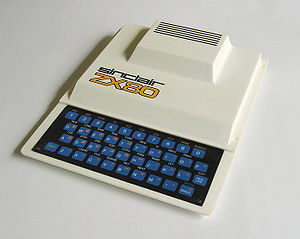

RH: Kids coming of age at that time were like, okay, what’s my new entertainment? In England we were blessed with a homegrown set of computers, the ZX80 and the ZX81, the Acorn Atom, and the BBC Micro, which was actually put out by the BBC Corporation. You could buy games, but they were very expensive, like thirty pounds for a text-based game. So programming your own was very common. You’d buy magazines and transcribe the programs—which is a great way to learn how to program, since even if you’re just blind copying, you’re still learning little bits of how it works—or steal games on cassette and do audio-to-audio piracy.

In part this was because the economy was bad. You know, bless her heart, there are many things I disagreed with Margaret Thatcher about [chuckles], but she did come in and change the way the country looked at things, for instance related to small businesses and people bypassing bureaucracy and doing things by themselves. Punk was just hitting—a whole new wave of music that people were making themselves. Gaming was a part of that same movement. Which is in stark contrast to later on, when consoles came about. With consoles, you don’t DIY program. Or at least it’s very, very hard. When consoles became the dominant force, we saw a big drop-off in bedroom programmers.

EG: And now we’ve got a reemergence of consumer-facing tools, where people can build their own games again. Producers to consumers to producers again.

RH: In gaming there’s always been an ebb and flow between closed platforms and open platforms. With open platforms, no one can stop you from publishing a game immediately yourself. And these days it’s infinitely easier with the Internet. Back in the day, to distribute your game you’d make copies on floppy disks and mail them out, or try and get a retail presence.

EG: You’ve toggled back and forth between the business side of games and being an independent game maker. Do you see it as a dual life?

RH: Maybe not in those words precisely. Whenever I’m not doing one, I want to do the other. It’s like there’s a gravity in the middle that I can never quite hit. I’ve been a professional game developer my whole life. I started out as a game designer and a programmer. And then I got into production and then management, heading up entire studios. So I’ve always been working with the business of scale. Some of the numbers are very large and that’s great, thrilling. But at the same time, I’m constantly making games personally. When I get home from working on games all day, I make games in my spare time for fun—which probably tells you I’m a broken human being, ha!

EG: I think it’s called being driven or possessed by the muse. What sorts of things have been surprising to you about the more widely used games you’ve worked on?

RH: The hunger for players to express themselves. In The Sims, I was always taken with just how sticky and compelling it was to make a house and a little person, and then to play with them. The power of that is spectacular to behold. We saw it in Second Life, even more so.

User creativity and the hunger for it constantly surprises and delights me. There are few greater feelings in business than to think to yourself each morning, I wonder what several million people have come up with overnight? And sure enough, you look at the latest uploads and it’s great stuff. All of these stories that people are telling just because they want to tell them.

EG: What would be an early instance of you noticing that, in a game you were responsible for?

RH: The very first game I commercially designed and released was called The Humans. It did really well. It was a puzzle game, a bit like Lemmings. You have to get these post-Neanderthal humans from one end of the level to the other. But they have to cooperate—lift each other up over something, or one of them may pole vault using a spear over a gap, and then throw the spear back so that the next person can vault over. I was blown away at how much pride people took in sharing their different techniques for beating levels—often things I’d never thought of.

EG: Has the sense of what a game actually is evolved over time?

RH: If you look at the PC gaming charts right now, they’re dominated by what we call sandbox games. It’s less directed, and you get to play with all the toys in the sandbox. Games like Kerbal Space Program, Minecraft, and Garry’s Mod all have this notion that how you play a game and show it to other people is way more important than beating the game. In fact, beating a game has become almost an old-fashioned idea.

That cultural shift has happened at an astonishing rate. I’ve got a son and a daughter, and both of them love making things within games or apps and sharing them, which I find very empowering.

EG: People want that agency now, for instance designing your avatar before you start playing.

RH: I’ll share a funny anecdote with you. In focus groups for The Sims, we discovered that about a third of the people would never leave the stage of Create a Sim. It wasn’t that they were confused; they were just like, “No, no, I only want make a person, so leave me alone. I’m having a great time.” “But we spent like a hundred million dollars building the rest of this game! Could you please go in and try it?” “No, I’m totally fine making people.”

EG: Let’s talk about your independent game design. What personal games have you made?

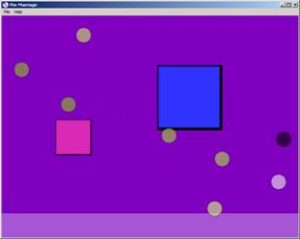

RH: I have to feel the subjects very personally. One of the early ones, that was relatively famous, was The Marriage, which was about how my wife and I viewed our marriage from different perspectives.

EG: How exactly did you make the mechanics of the game express the two different perspectives?

RH: You have two squares. One’s pink, one’s blue—it’s not very subtle. Actually I need to make a version of it with pink and pink, and blue and blue; a few friends have asked for that. Anyway, they drift around the screen. And when you mouse over them they start to move toward each other. So you are the agent of love. It’s a love story.

However, when you impact the couple, the pink square might get bigger and the blue square smaller. Which was my way of expressing, hey, I need space. And then there are things coming from the top of the screen, which are outside events—in my case, it was work or creativity. When those outside events hit the blue player, it gets regenerated. Like, okay, whew, I’ve had my breather; now I’m ready to reengage in the marriage. And then over time, colors in the backgrounds change, until the end, when it goes dark and both partners die.

The subtle part, which people tend to miss, is that what looks to be a star field appears, but actually it’s a memory of every single point where the couple has kissed throughout the entire game.

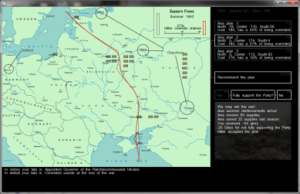

EG: That’s very poignant. STAVKA-OKH couldn’t be more different!

RH: That game is about how it feels to be in a bureaucracy in a totalitarian state. It’s a war game, and you are a cog in the administration of either the Soviet or the German war machine in World War II. You’re a middle manager, picking options to present up to the crazy dictator.

It was a direct reaction to reading about the postwar lives of Soviet and German staff generals. Quite a few Soviet generals, who were on the winning side, ended up getting executed after the war by Stalin, whereas Adolf Heusinger, who was on the German (losing) side, ended up the head of NATO. The idea was: Is there a way to look at the decisions I make when, yes, I kind of want my side to win, but I’m much more concerned about what happens to me after the war?

EG: What kinds of feedback did that game generate?

RH: I should preface my response by noting that a lot of World War II games don’t cover the Holocaust and the genocides. It’s disturbing. So in STAVKA-OKH you can decide to support the party or not. If you don’t, you get negative ratings from the dictator but your life after the war is going to be better, because you’re not turning a blind eye to the atrocities your side is committing.

If you do support the party, the inverse is true, but you also get this strange map overlay, in which little red circles expand at various points around the map. They are representations of the thousands of people who were massacred in certain locations, or deported, every month through the entire war. To do this I researched those numbers, counted up the individuals who were murdered, and then represented them as little pixels. I cried.

EG: Oh my god.

RH: Of course I had to consider, am I insulting the victims by reducing their lives and numbers to single pixels? Or is it a greater insult—I think so—to not acknowledge it at all? When people ask, “Hey, I love the game, but what are those red circles?” I’ll tell them and, you know, we all just bawl.

EG: That’s one of the things that art is supposed to do, right? Give people a wake-up call. What are things that make good subjects for games? And why?

RH: Any game has mechanics, and those mechanics are very much an expression of the author. So for me personally, free will and destiny are definitely important. And what art form is better equipped to handle that subject than something that’s interactive, that you get to make choices in?

I also think subjects of power, and of love, are good fits. Again, because it’s interactive and closely related to free will. People who fall in love—literally fall in love—tend to feel they don’t have a choice. It’s scary yet wonderful. And then if you spend decades with someone, as I have with my wife, you also have this great recognition that we have each chosen to spend time with this person, of our own volition. And we have made so many choices along the way that have kept that relationship going and fresh, with the knowledge that we could’ve made choices that would make permanent wounds.

EG: It’s interesting to hear you talk about things like class and power, the hand you’re dealt or the rules you’re playing by.

RH: Power is choice, really. And who has the choice? Where you put that on the line is extremely important.

EG: What’s an example of something that has gone away in gaming?

RH: Button mashing. Decades ago, pressing buttons very rapidly—for example to simulate running—was a “thing.”

EG: Like early Tekken.

RH: Exactly. It’s slowed down and become more strategic. With a really high-quality Street Fighter player, no way are they button mashing. It’s like they’re playing extremely high-speed chess, on the fly, dynamically putting together moves and combos that they’ve memorized.

EG: There’s such an interesting space right now with games and gender. Can you talk about some trends that you’re seeing in the world of independent games? Are they perhaps reacting to certain aspects of the mainstream games industry?

RH: I’ll give a particular shout-out to queer games. Over the past decade or so, that’s come from almost a zero level of awareness to leading the charge in romance and erotica—erotic gaming.

EG: Can you give a couple of examples?

RH: Gone Home is the famous one. Others include games by Robbie Yang, a New York gay artist and a friend of mine. He does a bunch of gay games, for instance, you can go into a shower and lather up this guy, and then it sort of gets disturbing over time, you’re pushing water into his face, until he’s almost drowning. Zoe Quinn just did a Kickstarter to put out this very interesting game with guys being objectified as sex objects.

Lots of people from the generation brought up on Nintendo games have gone into engineering or game design. They want to use the medium to express their stories and their identities—and happily, a massive portion of them are women. Also people who want to bring their race to games. Like, hey, I don’t see any black Mario, I want to make games that talk about my culture.

EG: In the original Super Mario Bros., you could be an Italian plumber or an Italian plumber! Finally with Mario Kart, you could be the princess. But it took a while. And certainly the games business still has some entrenched sexism.

RH: Right, like some woman in Chainmail Bikini fighting a guy wearing full-plate armor. I don’t think that’s how a battle would happen, you know. So there’s been a lot of reversals about it, people making games where the guy’s in a thong and the woman has full-plate armor.

EG: I agree that things are definitely getting better in that respect.

RH: Lara Croft came along and just blew certain assumptions out of the water. From the trailers for the previous Grand Theft Auto, you almost thought for a second that the main hero was going to be a woman, but they didn’t have the guts to do it. I was incredibly dismayed.

Mafia III just launched, a very successful game, really well done. It’s a black character, and you play in the South, with people racially abusing you the whole time. I think there is a wide acceptance among gamers. They just want great games.

EG: What are some of your great hopes for gaming?

RH: My biggest hope is that people will start to think of games in a more high-art way. They can be such useful tools for perceiving the world differently. Gaming is the dominant form of entertainment in the world today, in the sense that it makes the most money and is played by the most people. But when people think about high art, they’re not quite ready to go there.

EG: What can art do that games also do?

RH: As I mentioned earlier, great art can give you a new way of looking at things. It can make you feel something that you didn’t expect. It can turn you into a broader person. And games can demonstrably do those things as well.