SFMOMA’s archives department is located in a nondescript building in South San Francisco. Its beige exterior is a far cry from the museum’s rippling hub on Third Street, but for those who love art and artists, its contents could rival the galleries for thrills.

Launched in 2006 with a Getty Foundation Grant, the department’s mission is to record SFMOMA’s daily life, from the mundane to the extraordinary. Correspondence, photographs, oral histories, scribbled notes, and memorabilia — it’s all here, dating back to the museum’s founding in 1935. A record of Ruth Asawa’s parking ticket from 1973 sits in one file; nearby, memos from Ansel Adams show he had serious trouble getting his slides to work before a high-stakes lecture in 1944. Perhaps Grace McCann Morley went over and told him, one luminary to another, to try turning the projector off and back on again.

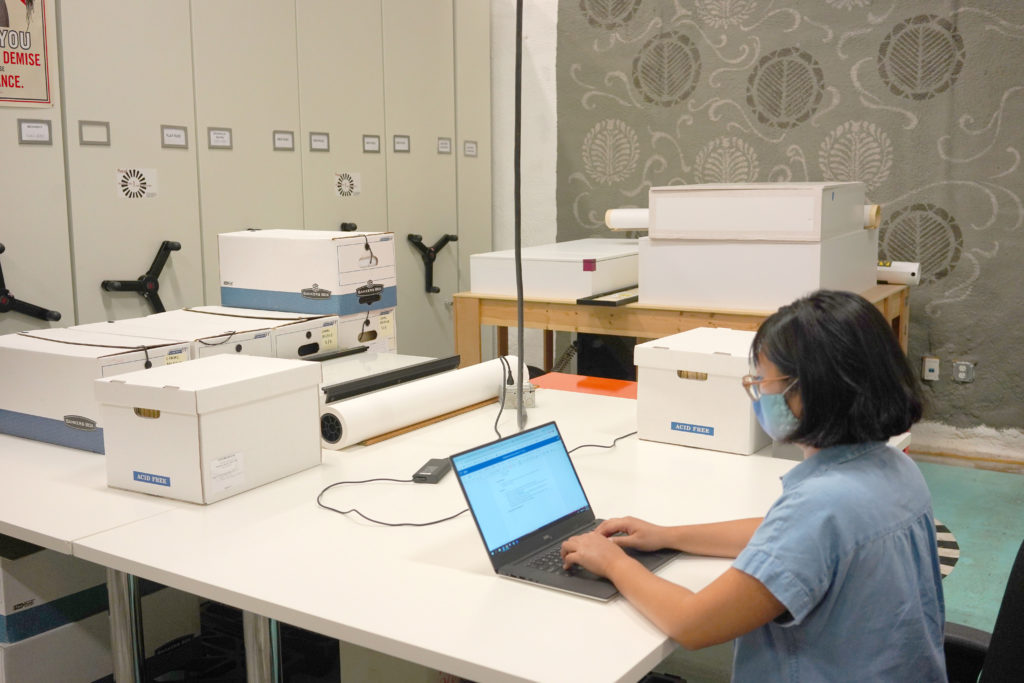

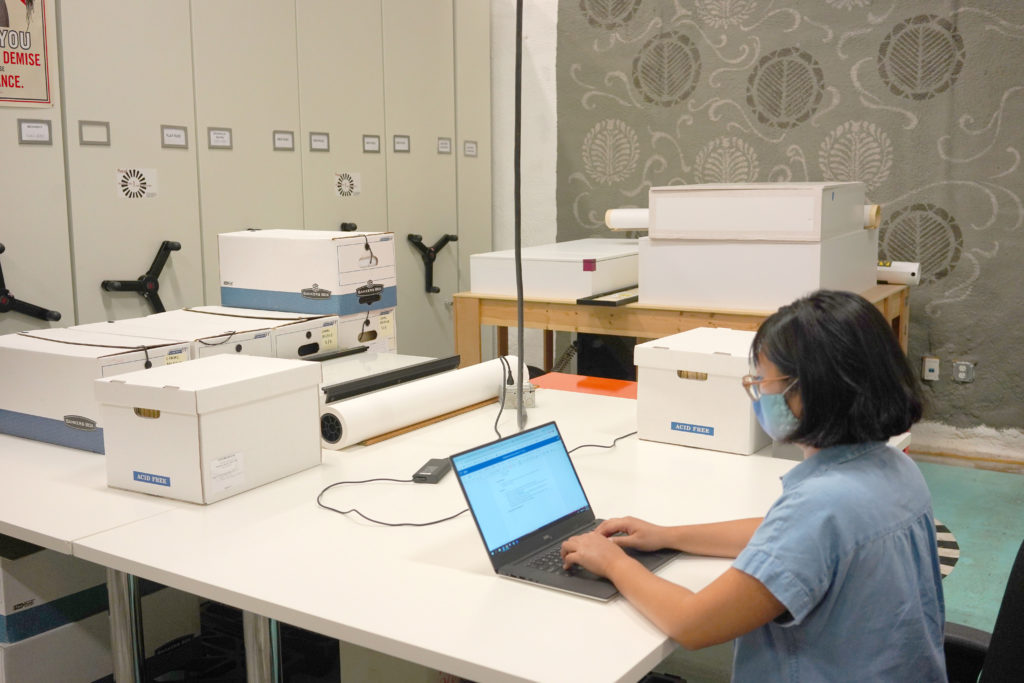

More curios abound in the archives’ maze of metal cabinets and nearly 3,000 boxes. Keeping track of the inventory are archives manager Peggy Tran-Le and associate records manager Meg Ocampo. The goal, they say, is to preserve not only the object but also a larger sense of process. If a curator works on a show with an artist and keeps all paperwork in a red folder, the materials come to the archives in that red folder; details matter.

Once a folder or object arrives in the archives, it has a place. There’s no rummaging necessary. “It’s not ‘digging’ through archives,” jokes Tran-Le, battling her least-favorite misconception. “That implies there’s no organizational system.” Ocampo goes a step further: “People have this image of Raiders of the Lost Ark when they think of archives, and it’s not like that,” she says, invoking Steven Spielberg’s archeological blockbuster. There are no mystical maps in the archives, just written finding aids, and the only way to rescue a relic is to follow strict department procedures.

Storing objects in rigorous order allows Tran-Le, Ocampo, and Ella Milliken Detro, the library and archives coordinator, to fill the deluge of requests they receive from staff, plus inquiries from students eager to snag a document for a thesis or dissertation. Sometimes, the requests are more offbeat, like one from a man asking about a Christmas contest hosted by SFMOMA’s Women’s Board (now the Modern Art Council) in 1966. “He had been telling his grandchildren about this amazing felt toy his mother submitted to that contest and won,” Tran-Le recalls. “He reached out, asking, ‘is there any documentation of this thing that my mother did?’” Tran-Le quickly found a record of the toy, and the man was thrilled.

More frequently, requests center on historical events colliding with museum operations. Popular files include documents from the 1940s that describe blocking the museum’s skylight before potential WWII air raids, correspondence between Japanese-American artists and Morley during the days of internment camps, and rebukes to lawmakers who wanted to destroy local art accused of Communist sympathies in the 1950s.

At work in the archives, Tran-Le appraises a drawer of objects and memorabilia from previous exhibitions.

Given its unprecedented nature, 2020 is bound to unleash its own flood of requests. There’s a dizzying amount for the archivists to document this year: the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum’s resulting closure, and the institution’s much-needed, very public reckoning over systemic racism. Tran-Le and Ocampo have been collecting at a clip, saving evidence of canceled exhibitions, enhanced safety measures, new Diversity, Equity, and Belonging plans, notes from fractious all-staff meetings, Instagram posts — along with the public response to all of it. “Future researchers are absolutely going to wonder how museums reacted to this moment,” Tran-Le says. “How were decisions made and how were they executed? It’s humanizing, and holds us accountable.”

Ocampo, too, wants to make sure everyone’s work finds a place in the archives, not just the most visible or highest in the hierarchy. “If we’re only getting something from one person, we’re only getting half the story,” she says.

More than ever before, the archivists are mindful of leaving gaps behind — those pesky black holes that breed mysteries or misleading narratives to frustrate successors. Both have encountered varying deficits during their tenures. Sometimes it’s a benign artifact that nags them for added context and shocks conservationist sensibilities, like a photo depicting Jackson Pollock’s Guardians of the Secret (1943) hanging above a groaning buffet table. In more dire instances, the absence of a record tells its own story to be filed under “cautionary tales.” Computers and the internet overtook hard copy in the 1990s and early 2000s, its novelty carving cavities in the archives. “We have a very complete record up until, like, the advent of the computer,” Tran-Le says.

Jackson Pollock’s Guardians of the Secret, 1943, hangs above a buffet banquet, circa 1950s; precise date unknown.

Now shed of its novelty, technology remains a problem for the archivists. Remote work during the pandemic tossed their concerns into greater relief, leaving Tran-Le and Ocampo more worried about how current generations will record this surreal time at SFMOMA and elsewhere. Fewer local newspapers mean less news about the arts, and information is often published on trendy, ephemeral social platforms, further reducing what they can pull into their trove. “We’re lucky to have one of the few archives departments in an art museum on the West Coast,” Tran-Le stresses. “And we try to stay on top of new technologies used at the museum. Yet whenever you’re using proprietary software, its makers don’t care about preservation or archiving. They’re not here to help you leave them.”

But Tran-Le and Ocampo are. They save the good, the bad, and the rote, hoping it’ll be enough for future generations to create a detailed and compelling portrait — or at least, an archivist’s version of one. Requiring no digging, of course.

“I always like to think,” Tran-le says, “one hundred years is right around the corner.”

Have a question for the Archives Department? Reach out at archives@sfmoma.org, visit the department webpage for more details.