Jesper Kouthoofd, head of design, founder, and CEO of teenage engineering, brings an explorer’s mindset to everything he approaches — from electronic products and graphic design to his Hammond organ and the gallery environment for SFMOMA’s exhibition Art of Noise. Curator of Architecture + Design Joseph Becker spoke with Kouthoofd to learn about his inspirations, his work style, and, perhaps what some fans are most curious about, the details of his personal sound system. (The interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Joseph Becker: Where does the name teenage engineering come from?

Jesper Kouthoofd: It comes from a song from almost 20 years ago by a Swedish band called Soundtrack of Our Lives. In the song “Teenage Angst,” it sounded to me that he was singing “teenage engineering.” We were building a little device, like what an Arduino is today, and had to come up with a company name and we picked teenage engineering. The company culture is like when you’re a teenager, you have this energy and will to try things, but you don’t have the full knowledge or skillset. It’s this discovery phase in life: going all in with open eyes and an open mind. teenage engineering is an attitude like, “Maybe we haven’t done it before, but let’s try. Let’s just do it.”

“teenage engineering is a good reminder to all of us to never get old — stay curious, stay naïve, and try new things.”

Becker: It’s like you’re harnessing some beautiful naïveté. You haven’t been bogged down by life telling you that you can’t do things.

Kouthoofd: Or how hard things really are. It’s exactly that. Naïve will. It’s what we discovered when we made our first product. We thought we were reaching 99% completion and then, oh, we have a thousand percent left to do with the manufacturing and all that. teenage engineering is a good reminder to all of us to never get old — stay curious, stay naïve, and try new things.

Becker: What were you doing before teenage engineering?

Kouthoofd: I went to school to study graphic design. I trained in the classic methods, using the camera and making everything by hand. I started doing record sleeves when I was 15. I got bored of that and wanted to get into advertising because it offered bigger budgets, more interesting projects. It was the early nineties when advertising was in a good place, with interesting people, creative campaigns, and some legendary commercials. I was an assistant art director on the Diesel Jeans campaign, which was quite big then. Then I started Acne and companies within Acne, like Netbabyworld, which was a gaming thing.

I’ve always followed new software, starting with Adobe Illustrator 88 in 1988, and how I could use the computer as a tool. The arrival of After Effects software allowed me to move graphics, which was how I turned to directing commercials and film production. I also always wanted to do CAD [computer automated design]. I started product industrial design because there was good software available. Interestingly, when I design nowadays, I sketch everything in 2D as I did when I started.

Becker: Acne was such an important company that had all of these tentacles. You created this ecosystem of cultural production. It seemed inevitable that you would then want to make something that could be handheld like a product.

Kouthoofd: I left advertising because I felt it used creativity only for print and film. Why wouldn’t we apply this creativity to making our own products? If you are a creative person, you don’t have to be stuck in one medium. When I design a product, it’s like making a film. You tell a story. A product can be entertaining and be a tool, which is a different way to think about industrial design.

Becker: Is that why you wanted to be part of Art of Noise?

Kouthoofd: Exactly. Culture and meeting people like you and understanding how that world works. Why do you do it? How do you think about things? Why are you interested in the stuff you do? It’s exploration. The adventure is so much bigger than developing and releasing a product. That discussion with the audience is super rewarding. If I discuss with you what teenage engineering is, I might change my mind tomorrow just to surprise you. When everything is cemented, it gets a little boring. The brain wants to be entertained. You still want to know a person or company — to see something from them that’s familiar but new. That’s what we try to find in everything we do.

Becker: What are some influences and inspirations behind your work?

Kouthoofd: When I started doing industrial design, I said the design philosophy should be a mix between German and Italian. I set up restrictions when I design. I always work with simple geometric shapes, RAL colors — which is a 40-color scale — and try to adhere to German industrial standards. The Germans thought out a system years ago that still works. They did such a proper job that you don’t have to reinvent things. I stick to rules and try to understand them, because then I can become free again. Like with colors, I started with Pantone, the industry standard, but they have too many colors, so it takes weeks to pick the right blue. If you use RAL, it has only two blues — light blue and dark blue. It’s about efficiency in the process and the expression.

I connect colors to a meaning and then apply that to all products. If it’s orange or red, it means recording. Colors and shapes are also connected, so a triangle is always yellow, a square is blue, and a circle is red. It’s this universal understanding about color and shapes. We also don’t use capital letters and only write in lower case. It’s democratic — why should certain words have more meaning and be capitalized? That’s an old-fashioned way of thinking about communication.

Inspiration also comes from learning; you start to question things. For a couple of years now I’ve questioned the point system used in typography. It’s meaningless today. I want to convert it to millimeters because I work in the metric system. And car manufacturers, I ask them, “Why do you have a hood on an electric car? There’s no engine there anymore.” Yet all electric cars are designed with a hood. How stupid is that? They say, “No, it’s the crash zone.” Yeah, but you can solve that in other ways.

Becker: I’m excited about many pieces in the show, like the DJ deck you designed for Virgil Abloh. How did that come about?

Kouthoofd: Virgil knocked on our door in Stockholm and we had a nice dinner together. He had this dream of reinventing the DJ deck, so I said, “Okay, let’s build something and start to explore.” This deck was the test. He used it when he performed at Coachella. We built it in two months. It can be scary to work with a creative superstar like him, but he was super down to earth and friendly.

I’m shy and he was also a little bit shy. We connected in that way. We both liked to work and discover things with our hands. He always picked up things and put them together, bits and pieces that he found at our office or the studio. It was the start of a creative process together that we sadly couldn’t finish.

I learned a lot watching him work. Instead of formal meetings, emails, and presentations, I would text him a snapshot of the display. We would text back and forth. Some people hate emojis, but the thumbs up and thumbs down are so effective when you are in a sensitive creative process. I’ve adopted that.

Becker: You bridge the analog and digital world in such an interesting way. What is the draw?

Kouthoofd: For me it’s about the muscle memory that connects to the experiences you had when you were young. Maybe you turned a knob or did something with your hands that you never forgot. Many people use mechanical keyboards because they remember the feeling of typing on a typewriter or a vintage keyboard. That feels better to them than a flat keyboard or touch screen. Now it’s display screens everywhere. Some people believe the next OS is away from touch, with people moving and doing gestures in the air. I think we will have physical things that we touch. But that’s just me.

Becker: I wanted to get at this with the exhibition. We have this contemporary trade-off where we can carry all of our music with us in our pockets, but you interact with it through a touchscreen. There isn’t the tangibility of the past in most people’s experience, but you reintroduce that bodily memory in a visceral way that is really inspiring.

“teenage engineering is an attitude like, “Maybe we haven’t done it before, but let’s try. Let’s just do it.””

Becker: What devices do you use to listen to music?

Kouthoofd: I’m into Hammond organs, so I’m trying to learn that. I have a B-3. Before the Hi-Fi system, some people had an organ in the home, and that was the musical entertainment system.

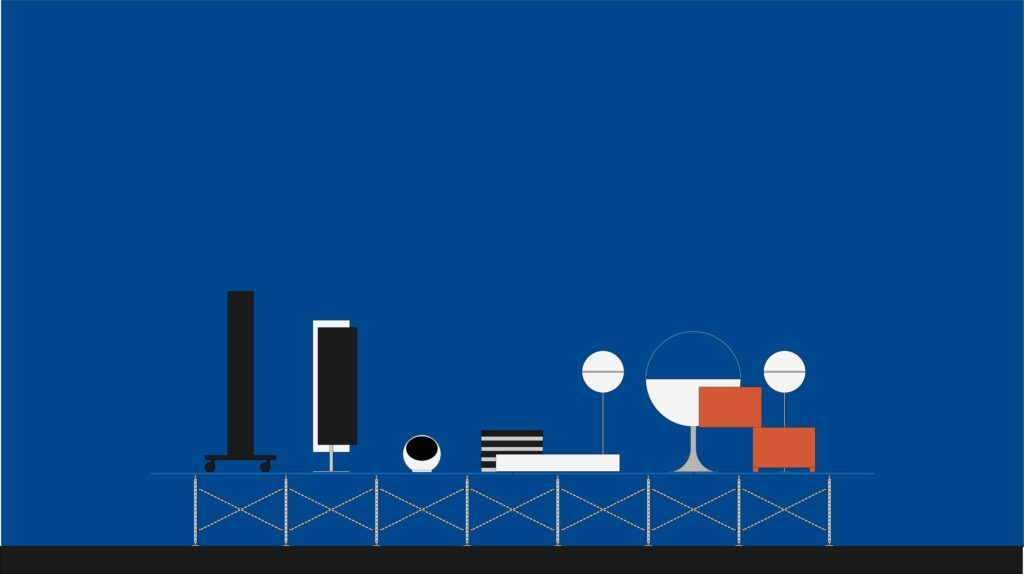

My Hi-Fi system today is an AM-1 mixing console — that’s my pre-amplifier, so to say. Then I have, and really like, JBL’s 4435 Studio Monitor speakers — they’re quite big, each one-by-one meter — and two monoblock class D amplifiers, one amplifier per channel. For me, it’s not about audiophile quality. If you have a lot of amplification power you don’t have to only use it to play loud, you can use it to EQ [equalize] the sound. I’m a bit like a sound engineer. When I listen to music, I EQ a lot to compensate for the room, for reflections, etc. I use the mixing console to monoblocks and then use the TX-6, our little mixer, as a sound card if I play digital music. For my turntable at home, I have the EMT 950. It has a time code and it’s the one the BBC used in their broadcasting.

Becker: What are you currently listening to?

Kouthoofd: Gospel and Hammond recordings. It’s hard to find really, really good records. They’re usually live recordings, but that’s what I try to listen to. I’m getting old. I get that. I’m turning into this Hammond old fart.

Becker: The Hammond has that analog warmth, but it’s a precursor to the synthesizer.

Kouthoofd: Exactly. It is basically a synth. If you look at old Roland synthesizers, they try to replicate real instruments. The 303 was created to replace the bass player. It’s the same with every instrument we do. The journey is long. It can take decades until people discover, “Oh, I can use it in this way.” Like how they started to scratch on a turntable, and it ended up being the technique that everyone wanted. It’s this randomness that is interesting.