Left: Henri Matisse, The Blue Window, 1913; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund; © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: digital image; © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Right: Richard Diebenkorn, Woman on a Porch, 1958; New Orleans Museum of Art, museum purchase through the National Endowment for the Arts Matching Grant; © the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

To be sure, there are dozens of major Henri Matisse works in the show, but Matisse/Diebenkorn is very much the story of Richard Diebenkorn and his decades-long engagement with the older artist. Curators Janet Bishop (of SFMOMA) and Katy Rothkopf (of The Baltimore Museum of Art) have carefully structured the exhibition as a series of encounters, which occur not only in real time, as visitors come upon the works, but also by way of time traveling, as they vicariously encounter Matisse through Diebenkorn’s eyes.

Curators Janet Bishop (left) and Katy Rothkopf. Photo: Maximilian Franz

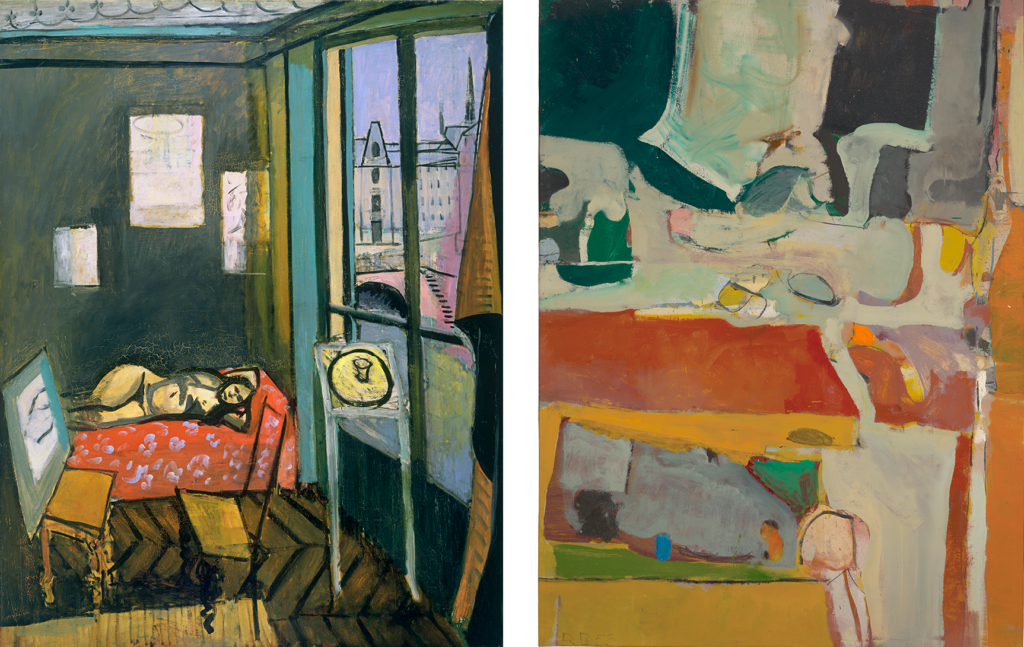

It’s a relationship that lasted half a century, and that followed Diebenkorn through three distinct phases of his career: his early years working in an Abstract Expressionist mode, his move to figuration starting in 1955, and his later return to abstraction. As curators, Bishop and Rothkopf had to be very active as “authors,” given how important it was to make particular pairings get particular points across. Sometimes visitors will come upon a juxtaposition of two very closely related works — a woman in a chair and a woman in a chair — but they’ll also find many instances of a figurative Matisse with an abstract Diebenkorn, and be called upon to do a little visual detective work to discover the “why” of it.

“One great example would be Matisse’s Goldfish and Palette (1914) and Diebenkorn’s Urbana #6 (1953),” notes Bishop. “I love it because there is such a clear relationship between the two paintings in palette and in structure. And if you look at the way Diebenkorn animated his composition with red splotches in the middle of the black field, it’s easy to see a connection to Matisse’s fish, even if the splotches aren’t meant to be actual fish. Matisse painted largely in a representational vein, but you definitely see the influence in Diebenkorn’s abstract periods as well. In Urbana #6 he’s taken several aspects of the Matisse and made them his own.”

Rothkopf agrees: “When people first walk into the show, they immediately encounter Diebenkorn’s earlier work, which was abstract, and they have to ‘acclimate’ to seeking out the connections. We tried to make effective juxtapositions that lead them into it, and then as the show progresses, it gets easier and easier, especially if they’re reading the wall texts or listening to the audio guide. The first Diebenkorn works in the exhibition date from 1953. He’d seen Goldfish and Palette and many more at the major Matisse retrospective at Los Angeles the previous year.”

Left: Henri Matisse, Goldfish and Palette, 1914; the Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift and bequest of Florene M. Schoenborn and Samuel A. Marx; © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Right: Richard Diebenkorn, Urbana #6, 1953; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, museum purchase, Sid W. Richardson Foundation Endowment Fund; © the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

Visitors will not encounter the Matisse works chronologically (by the date of their making), but rather through the chronology of Diebenkorn’s career. It’s a unique and engaging way to understand the oeuvre of an artist, especially one as visually voracious as Diebenkorn, who was an incredible student of art history with a prodigious visual memory.

“In most cases, it isn’t a one-to-one kind of thing,” notes Bishop. “It’s not a ‘pairs’ show per se. But there is absolutely a direct conversation going on. Throughout the exhibition, we chose works by Matisse that we either knew to be important to Diebenkorn because he mentioned them specifically, or ones where we could see the resonances.”

Left: Henri Matisse, Studio, Quai Saint-Michel, 1916; the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Right: Richard Diebenkorn, Urbana #4, 1953; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, gift of Julianne Kemper Gilliam; © the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

Diebenkorn passed away in 1993, but many resources were available to do the necessary research. There are interviews at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, and quotes in articles and reviews. His wife, Phyllis, lived until 2015 and was happy to share information, as were his daughter Gretchen and his son-in-law Dick Grant. Curators with whom he had conversations were also forthcoming, among them John Elderfield, who wrote the introductory essay for the catalogue. Elderfield had a long-standing relationship with Diebenkorn and noted that he often spoke about Matisse as an inspiration. Rothkopf even interviewed the diplomat who escorted Diebenkorn and his wife around the Soviet Union in 1964, to visit artists’ studios and museums to see works by Matisse and others. Bishop and Rothkopf also relied on conversations with Diebenkorn’s friends and students, the work of many other curators and scholars, and the extraordinary research done by the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation over the course of the preparation of the catalogue raisonné.

One new source was a letter that Diebenkorn wrote to a Canadian graduate student in which he outlined his encounters with Matisse’s work and mentioned the 1914 to 1918 paintings as particularly important to him. “A curatorial colleague of ours working on a different Matisse project sent it to me,” says Rothkopf: “‘Oh, by the way, here’s a letter that I assume you’ve seen?’ We were thrilled. One of the things about working on a show for a very long time is that you’ve talked about it so much, people know you’re working on it, and sometimes these wonderful gifts fall out of the sky.”

SFMOMA was a home museum for Diebenkorn, who grew up in San Francisco and went to Stanford. But the letter also had the great advantage of bringing The Baltimore Museum of Art, Rothkopf’s institution, into the narrative. In the letter, Diebenkorn recalls that he went to Baltimore in 1947 and saw the Cone Collection. “We never knew we were part of his early interactions with Matisse’s work, but it turns out we were right there.”

Students of local art history will likely know the story of the Bay Area Figurative movement—how in the early 1950s, several artists, including David Park, Elmer Bischoff, and Diebenkorn—turned away from the Abstract Expressionism that then dominated the art world and began painting figuratively. (Park famously took a carload of his earlier abstract canvases to the dump.) Bishop notes that in some ways it was a bolder and riskier move for Diebenkorn than for the others involved. Whereas Park’s Abstract Expressionist career never fully got off the ground, Diebenkorn’s had been quite successful. But, as he famously said, “For someone who was intending to continue as an abstract painter, I was clearly consorting with the wrong company.”

“It wasn’t that Matisse or any other historical artist specifically influenced his shift in 1955,” clarifies Bishop. “It was more that he was spending a lot of time with Park, who had by then been painting representationally for a good five years, and Bischoff, who had been painting representationally for two or three years. So he felt like if he wanted to be where the action was, he needed to paint figuratively as well. However, once he did make the shift, it’s interesting how closely his subject matter aligned with Matisse’s. In Matisse’s work you find precedent for so many of the types of subjects Diebenkorn painted, whether they’re still lifes, women in chairs, or views out the window.”

Left: Henri Matisse, Femme au chapeau (Woman with a Hat), 1905; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, bequest of Elise S. Haas; © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Right: Richard Diebenkorn, Seated Figure with Hat, 1967; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, gift of the Collectors Committee and Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence Rubin; © the Richard Diebenkorn Foundation

And luckily for us, Diebenkorn didn’t take his older paintings to the dump. In fact, he felt quite the opposite way about them. Bishop met him once toward the end of his life, at the time of a Whitechapel-organized retrospective that SFMOMA hosted, and remembers walking with him through the galleries alongside his wheelchair. “He absolutely loved looking at all of the works. Some artists don’t like looking back at things they made years earlier. But Diebenkorn really, really enjoyed revisiting every single one.”

Visitors will also enjoy a vicarious encounter with Matisse by way of Diebenkorn’s personal library, which makes clear that his experience of the older artist wasn’t limited to things he’d seen firsthand in exhibitions. Once he purchased Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s Matisse: His Art and His Public in 1954, he added to his Matisse library at every opportunity. SFMOMA has twelve of his books in vitrines, situated throughout the show, open to particular pages that reveal “Matisse moments.” Several of the books have notes, postcards, and articles tucked into the pages, and even served as scrapbooks into which he’d paste illustrations or reproductions that he acquired elsewhere. Some of them show a lot more signs of wear (read: affection) than others.

The books serve several purposes, notes Rothkopf: “One, they allow us to ‘include’ paintings and drawings in the gallery without necessarily getting them as actual loans, which is neat: we can still curate without necessarily borrowing something.” Second, a few books are open to black-and-white images of oil paintings, which reminds visitors how Diebenkorn would have first encountered many of these works. “Today, we’re so used to seeing everything in color (and instantaneously). For him, seeing a work in black and white had particular advantages—specifically it enabled him to more easily perceive the structure of a painting, without the distraction of color.”